Background and Objectives: Despite the prevalence of published opinions about the use of professional academic writers to help disseminate the results of clinical research, particularly opinions about the use of ghost writers, very little information has been published on the possible roles for professional writers within academic medical departments or the mechanisms by which these departments can hire and compensate such writers. To begin addressing this lack of information, the Association of Departments of Family Medicine hosted an online discussion and a subsequent webinar in which we obtained input from three departments of family medicine in the United States regarding their use of academic writers. This discussion revealed three basic models by which academic writers have benefitted these departments: (1) grant writing support, (2) research and academic support for clinical faculty, and (3) departmental communication support. Drawing on specific examples from these institutions, the purpose of this paper is to describe the key support activities, advantages, disadvantages, and funding opportunities for each model for other departments to consider and adapt.

In academic medicine, faculty roles typically include clinical care as well as the teaching and research expected in other fields of academia. For these faculty, the time investment to initiate, organize, find funding for, and disseminate findings from an area of scholarship is formidable. One option for supporting scholarship is to work with an academic writer. Although academic writers are often used to support research efforts specifically, these individuals can support a department in roles beyond those related to research as well.

Published information about the roles of academic writers within departments is limited, however. Searches of the published medical literature using the terms “academic writers” or “medical writers” elicit articles that focus on how to write manuscripts,1-4 give opinions about working with professional writers,5-7 highlight the need to acknowledge medical writers in publications as part of “good publication practice” standards,8-9 and strongly discourage the use of ghost writers.10-14 Alternatively, an internet search for “academic writer” returns multiple commercial websites, and it is difficult to know which to choose without any framework or prior knowledge. It is also clear that some academic writers work as part of the infrastructure of departments or research centers, but little information about their specific roles exists outside of local institutions.

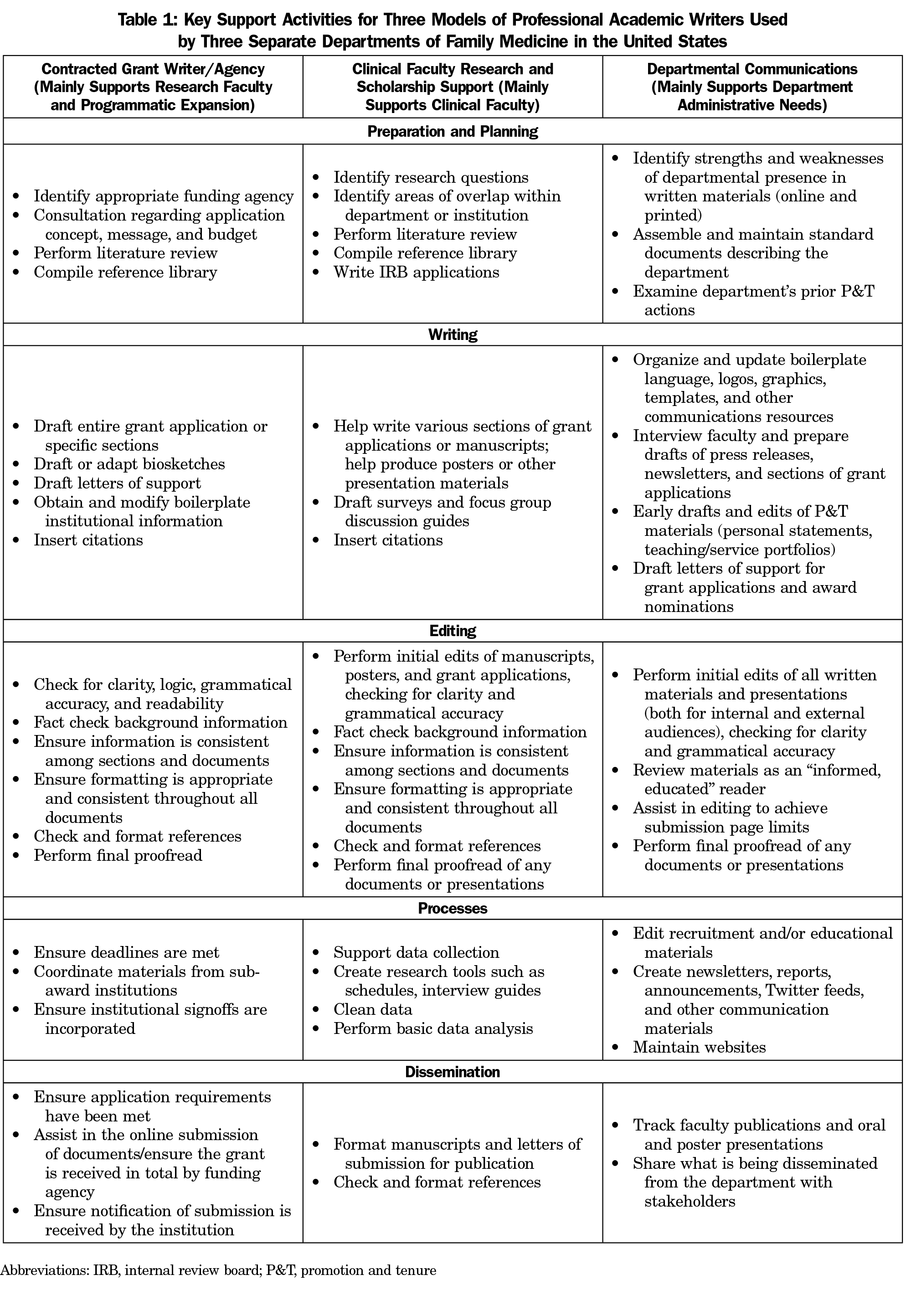

Given the limited information available about the roles of academic writers within departments and following a robust online discussion, the Association of Departments of Family Medicine (ADFM) sponsored a webinar about the role of academic writers within departments of family medicine, which provided the genesis for this article. ADFM is the membership organization that includes virtually all allopathic departments of family medicine in the United States, as well as some osteopathic departments and some departments in large academic health systems that are not part of a medical school. Department members attending the webinar expressed a need for the support of an academic writer, but most knew little about finding and funding these individuals or about their specific roles. Recognizing this widespread challenge, we explored some of the creative and adaptive solutions departments have found. Three department chairs and their academic writers, two other chairs who had academic writers in their departments, and two academic administrators and researchers formed the writing group for this paper. We share the three main models we identified through our discussions about academic writer positions: grant writer, research/publication support, and departmental communications. In addition, we describe the roles and responsibilities for each model (Table 1), the necessary skill sets, the expected returns on investment (Table 2), and common mechanisms for funding academic writers (Table 3), recognizing that department or institutional needs and resources will vary and shape the role(s) of their particular academic writer.

Three Models of Academic Writers

Model #1: Grant Writers

In the quest for funding, identifying agencies to help fund a program or research may be the easiest step; addressing the unique and often extensive requirements for each grant application in a clear and concise manner may be the most difficult. Our discussion provided insight regarding ways in which a department or faculty member could employ academic writers to improve or expedite the process of writing and submitting grant applications.

To facilitate the submission of grant applications, the University of Alabama at Birmingham Department of Family and Community Medicine (UAB DFCM) has worked with a contracted grant writer. This medical writer, who reports to the department chair, has doctoral and postdoctoral experience in preclinical research and focuses professionally on writing and editing health-related research grant applications and manuscripts pertaining to research and training in health-related fields. With the assistance of this individual, the UAB DFCM recently secured a Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) grant for $7M (T99 Medical Student Education Grant, $1.75M for 4 years). Alternatively, the University of Utah Department of Family and Preventive Medicine has a grant writer on staff. This individual has a humanities PhD and is embedded as part of the proposal development team in the Central Research Office, reporting to the director of research.

A grant writer, whether hired as a contractor or as an employee, can assist faculty throughout the entire application process, from helping determine which grants best fit their needs and focus to drafting or editing the proposal, ensuring clarity and readability, and confirming that each application-specific requirement is appropriately addressed. This person may perform many of the most time-consuming, but critical, tasks required to produce a competitive proposal. Notably, a grant writer can ensure that information is consistent throughout the various components of the application, which is critically important for center grants, program project grants, or other large multidisciplinary grants involving multiple departments or institutions. One of the most valuable aspects of enlisting a grant writer is their ability to point out weaknesses in logic and gaps in clarity.

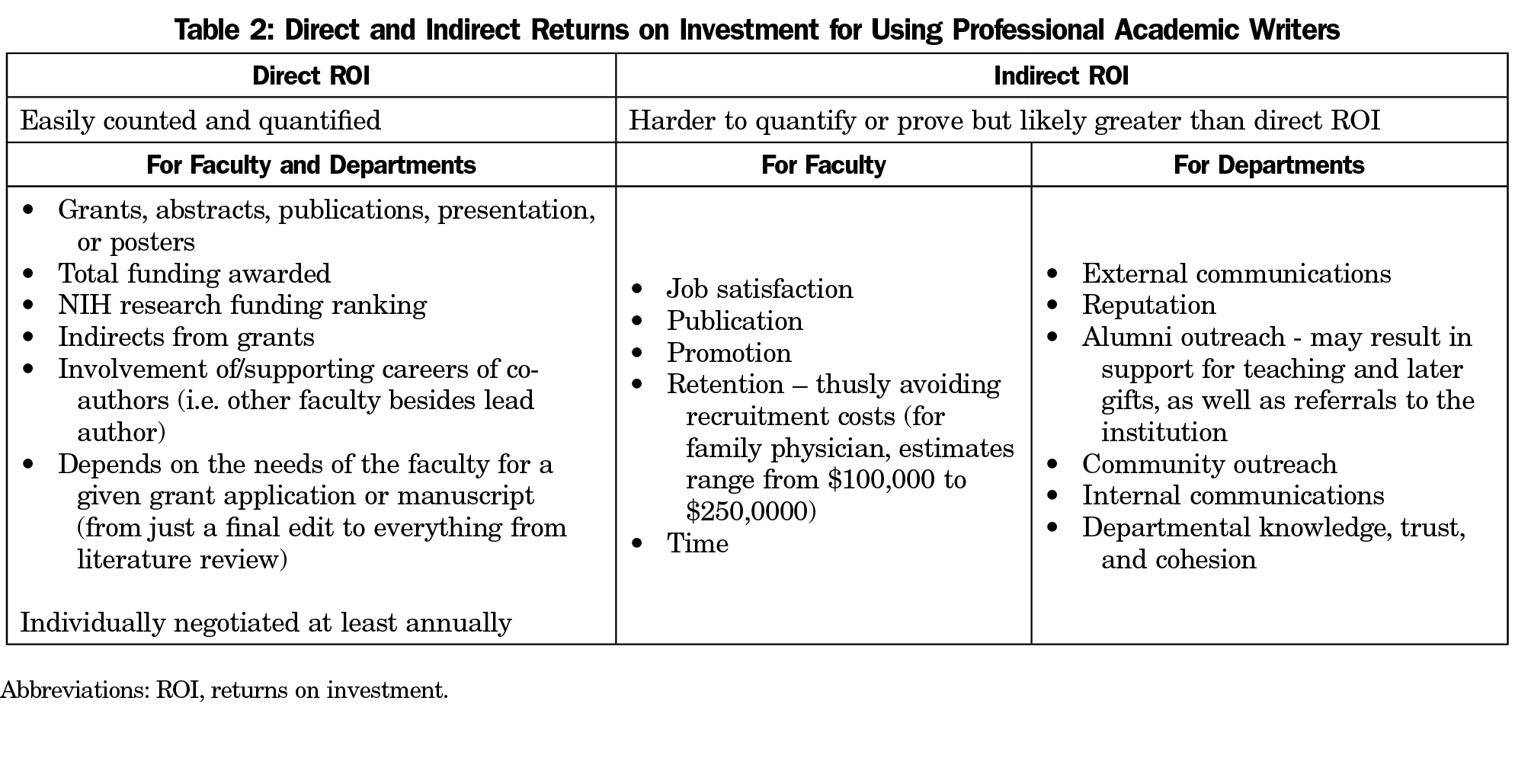

In our experience (at UAB and Utah), grant writers provide a good return on investment in the number of grants submitted and funded. Financially, grant writers are likely to pay for themselves by increasing the number of awarded grants. Moreover, our experience indicates that the assistance of a grant writer also allows the faculty members submitting the grant to better concentrate their efforts. This in turn increases faculty satisfaction and allows them more time to concentrate on publications and research or other work to support further grant applications. Returns on investment for all three models described in this paper are summarized in Table 2.

It is worth noting here the alternate role of expert grant reviewers as well. These individuals, usually from outside the institution, are experts in the field and review grant proposals prior to final submission to a funding agency. The detailed critiques provided by these expert reviewers allow the submitter to preemptively address concerns that may otherwise be raised by the review panel or study section.

Model #2: Research and Scholarship Support to Clinical Faculty

Dividing research support resources among faculty can be a delicate and complicated balancing act. If done appropriately, faculty will feel more valued and connected to the greater department, which in turn increases productivity, satisfaction, commitment, and retention. Clinical faculty in particular often have much less exposure to the publication process and limited time to learn it. Indeed, clinical faculty may feel intimidated by the research and publication process and undervalued by their research-driven counterparts, who in comparison may have significant staff support, often funded by their grants. Our collective experiences show that offering basic research and publication support to clinical faculty increases the likelihood of clinical faculty publications, promotion, job commitment, and job satisfaction—all worthy returns on investment.

The specifics of clinical faculty support will vary by institution, depending on the types of resources available. In our described model, from the University of Michigan Department of Family Medicine, the department hired an administrative specialist who is shared among clinical faculty and functions as a high-level research assistant. She has a master’s degree in sociology and experience in social science and market research and reports to the department administrator. However, similar to grant writing support, research and publication support can be obtained on a contractual basis as well.

A key to success is the ability of the clinical faculty support person to be flexible, supportive, and persistent while also understanding and respecting the clinical faculty culture, which often necessitates meeting cancellations due to clinical obligations, delays in deliverables, and other related complications. Clinical faculty appreciate the crucial research and publication assistance as well as encouragement, reminders, and overall coaching provided by this individual. Our clinical faculty support person provides assistance in four key areas.

First, she can help faculty identify interests, research ideas and questions, and the next steps necessary in their scholarly process, including short- and long-term goals. This may include identifying the areas in which clinical faculty would like support as well as connecting them to research faculty with overlapping interests or project content. Second, she can help with preliminary study preparation, including assisting faculty with a literature review, survey design, and document submission to the internal review board (IRB). Third, she can assist in project management and data gathering. In this regard, she may assign roles, create work aids (eg, timelines), and help keep the project on schedule. One role that is invaluable to clinical faculty is helping to check, clean, and prepare data for analysis and to organize additional analytic or statistical support available in-house or accessible within the institution. Finally, she helps with the dissemination of results. This may involve preparing materials for presentation and posters as well as editing and formatting manuscripts prior to submission.

The success of clinical faculty in their scholarly endeavors benefits an entire department. In our experience, producing more engaged and expert faculty, with the scholarly products for promotion, leads to a cooperative and supportive environment. Such an environment enhances faculty satisfaction, retention, and connection to the mission of the larger department and institution.

Model #3: Departmental Communications (and Other Writing)

The administration of an academic department regularly engages with many constituencies, including current faculty and staff; community and public officials; the dean’s office and the health system; alumni and donors; promotion and tenure committees; and legislators and national leaders. Necessary materials include everything from letters of reference to position papers and cross multiple formats, including digital materials for websites and social media feeds, print materials for newsletters, official correspondence, and reports. To ensure the high quality and consistency of internal and external communications for diverse audiences, the Emory University Department of Family and Preventive Medicine (Emory DFPM) hired an internal communications specialist to work closely with leadership and faculty. This communications specialist works under the human resources title of communications manager and reports to the lead department administrator and department chair. She handles a variety of duties ranging from faculty development to marketing and communications, to direct support for the chair. She has also provided research and publication support, as described in models 1 and 2 above. A background in the sciences is not necessarily required for this position; the Emory DFPM communications manager has a doctorate in English literature and a master’s degree in creative writing.

Of particular relevance for the Emory DFPM leadership, the departmental communications specialist drafts appointment, promotion, and tenure letters and dossiers, as well as letters of nomination, support, and reference for faculty career development opportunities and awards. Because she is familiar with the faculty’s scholarship, service, teaching activities, and honors, she has disseminated information in internal newsletters, annual reports, and university and school of medicine publications. She has also made strategic improvements in the department promotion and tenure process. For example, the Emory DFPM has far fewer than the average number of promotion dossiers returned for substantial edits. Additionally, she has created a tip sheet to which faculty can refer while writing personal statements, and she coaches individual faculty members through early drafts if needed.

While some large departments may have separate staff to support faculty development, marketing, and communications, smaller departments may find it advantageous to combine these roles. In our experience at Emory, an in-house communications expert has positively influenced all departmental missions (education, scholarship, and clinical care), thus we suggest that departments may realize distinct benefits from bringing in someone with a background outside of medicine. For example, someone trained in the humanities can bring the perspective of the intelligent and engaged general reader; someone with past teaching experience may have the ability to teach workshops on CV maintenance or personal statement writing; and someone with a background in business or marketing can inform this perspective.

Advantages, Disadvantages, and Funding Each Model

We have reviewed examples of roles within departments of family medicine using three department-specific examples shared from the perspective of the department chair and the writer. The key support activities for each of these roles are summarized in Table 1. These roles overlap, and the individuals filling these roles in our examples have adapted to meet the particular needs of their departments. However, the needs of other departments will vary, thus clarity about what duties are expected—traditional grant support, clinical faculty research and scholarship support, and/or overarching communications-focused administrative support—is necessary for the academic writer to be successful.

Although the models are broadly applicable, each academic writer described in these models came to their department with different skill sets to meet the varied departmental needs. Two critical position characteristics identified by these three individuals include a clear expectation of their primary responsibilities and a defined and respected position within the department. Each type of academic writer described ultimately frees up faculty members’ time, further improving the success of individual faculty members and the department overall. Each writer also provides a worthwhile return on investment from the perspective of the department chair (Table 2). This return may range from more funded grants and faculty publications to faculty promotion, satisfaction, and retention, as well as overall departmental cohesion and success.

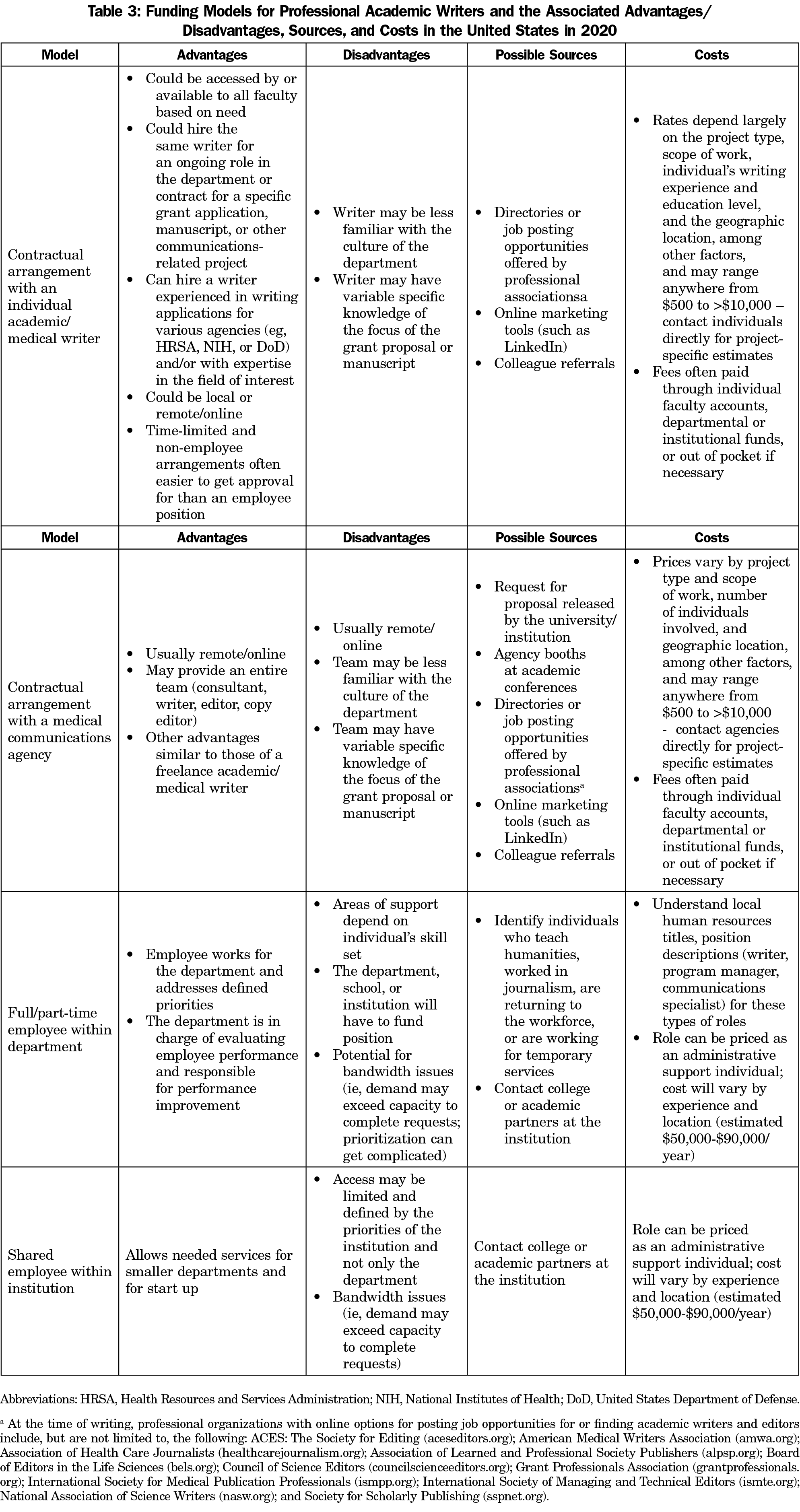

For those interested in applying one of these models in their own setting, logistics (eg, duties, reporting structures, and titles) and funding are often the main considerations. Table 3 describes multiple funding models, each with advantages and disadvantages, that may support an academic writer. For example, a departmental salaried employee responds to departmental priorities; however, no individual can do everything, and the cost resides within the department.

Institutions often provide salaried individuals who can perform many of the tasks described in these models as well. For example, individuals supporting grant submission may be found in an institution’s Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program or the research dean’s office, but access to this expertise may be limited, especially if the grant application is not of strategic priority for the institution or if multiple faculty are submitting at the same time. Administrative communications support may come from an office of marketing and communications or public relations, but the work often needs to be prioritized by the institutional entity and those priorities may not always align with the department’s goal.

Other support can be externally contracted by the department or by an individual faculty member. These services may be paid for by departments, other institutional units (eg, CTSA programs and training grants), individual grants or start-up funds, endowments, or philanthropy. However, careful evaluation is necessary to ensure that the contracted support has experience with the specific grant application, area of research focus, and/or the culture typically found in academic medical departments. Medical communications agencies and individual freelance academic/medical writers can be found through member directories and job posting opportunities provided by professional organizations, other online searches, or personal referrals (Table 3). Another important resource for a contract writer may be a graduate student in the health sciences, humanities, or other fields who can grow with the department.

Using common search engines and phrases, we found no published research describing models or types of academic writers within academic medical departments, centers, or medical institutions in general. We have described three possible models of academic writers for departments to consider and offer criteria by which to evaluate the fit of the model or person with the needs of the academic unit. This review emerges from the experiences of departments of family medicine only, and each example is unique. However, the overview and examples described will help departmental and health care leaders more rigorously consider the role of academic writers and their potential return on investment.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the interest of the members Association of Departments of Family Medicine in this topic that led to a discussion and this manuscript.

Presentations: The genesis of this manuscript was a discussion hosted by the Association of Departments of Family Medicine in August 2020 where the models described in this paper were shared with the membership of that organization.

References

- Yarris LM, Gottlieb M, Scott K, et al. Academic primer series: key papers about peer review. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(4):721-728. doi:10.5811/westjem.2017.2.33430

- Albert T. Eight questions to ask before writing an article. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2017;78(6):341-343. doi:10.12968/hmed.2017.78.6.341

- Grant MJ, Bonnett P, Sutton A, Marshall A, Murphy J, Spring H. Are you a budding academic writer? Health Info Libr J. 2016;33(1):1-6. doi:10.1111/hir.12137

- Švab I. The seven deadly sins writers of academic papers should avoid. Eur J Gen Pract. 2017;23(1):254-256. doi:10.1080/13814788.2017.1384809

- Donnelly JA, Marchington J, Gertel A, Stretton S. Professional writers can help to improve clarity of medical writing. CMAJ. 2018;190(9):E268. doi:10.1503/cmaj.68670

- Marchington JM, Burd GP. Author attitudes to professional medical writing support. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(10):2103-2108. doi:10.1185/03007995.2014.939618

- Jacobs A, Carpenter J, Donnelly J, et al; European Medical Writers Association’s Ghostwriting Task Force. The involvement of professional medical writers in medical publications: results of a Delphi study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(2):311-316. doi:10.1185/030079905X25569

- Anand G, Joshi M. Good publication practice guideline 3: evolving standards for medical writers. Perspect Clin Res. 2019;10(1):4-8. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_31_18

- Stocks A, Simcoe D, Toroser D, DeTora L. Substantial contribution and accountability: best authorship practices for medical writers in biomedical publications. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(6):1163-1168. doi:10.1080/03007995.2018.1451832

- Vera-Badillo FE, Napoleone M, Krzyzanowska MK, et al. Honorary and ghost authorship in reports of randomised clinical trials in oncology. Eur J Cancer. 2016;66:1-8. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2016.06.023

- Resnik DB, Tyler AM, Black JR, Kissling G. Authorship policies of scientific journals. J Med Ethics. 2016;42(3):199-202. doi:10.1136/medethics-2015-103171

- Baskin PK, Gross RA. Honorary and ghost authorship. BMJ. 2011;343(oct25 1):d6223. doi:10.1136/bmj.d6223

- Sismondo S, Doucet M. Publication ethics and the ghost management of medical publication. Bioethics. 2010;24(6):273-283. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.01702.x

- Anekwe TD. Profits and plagiarism: the case of medical ghostwriting. Bioethics. 2010;24(6):267-272. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00705.x

There are no comments for this article.