Background and Objectives: Role modeling and mentoring are key aspects of identity formation in medical school and likely influence student specialty choice. No reviews have examined the ways that mentorship relationships impact primary care career choice.

Methods: We conducted a systematic literature search to identify articles describing the influence of role models and mentorship on primary care interest, intention, or choice. A content analysis of the included articles determined which articles focused on mentorship versus role modeling and the definitions of each. We coded articles as groundwork, effectiveness, or impact depending on the methodology and outcomes of each study.

Results: Searches yielded 362 articles, of which 30 met inclusion criteria. Three offered definitions of role modeling, and one compared and contrasted definitions of mentoring; 17 articles laid groundwork that indicated that role modeling and mentorship are important factors in career choice and specifically in primary care. Thirteen articles reported the effectiveness and impact of role modeling and mentoring in influencing intent to enter primary care or actual career choice. Primary care and non-primary care physicians influenced student interest, intent, and choice of primary care careers; this influence could be positive or negative.

Conclusions: Role modeling and mentorship influence primary care career choice. Very few articles defined the studied relationships. More work on the impact of mentorship and role modeling on career choice is needed.

Role modeling and mentorship have been identified as critical to student choice of primary care (PC) and family medicine (FM) careers for more than three decades.1,2 Since primary care was defined by Dr Barbara Starfield and family medicine became a specialty, educators have studied how student relationships with physicians influence the kind of field they choose to enter.3,4 Though many articles have been published about role modeling and mentorship in primary care and family medicine over decades, there are no universally-accepted definitions of these terms. Clear definitions of these terms could help faculty effectively engage with students to support PC career choice and allow institutions and departments to devote scarce resources to evidence-based relationships that promote PC.

The goal of this study was to describe what is known about the influence of mentorship and role modeling on primary care career choice through a systematic review of the literature. Additional goals of this study were to explore published definitions of role modeling and mentoring that influence primary care career choice with the aim of clarifying a definition for each. The final goal of this study was to categorize the level of intervention for role modeling and mentoring, as described by the larger scoping review study.5

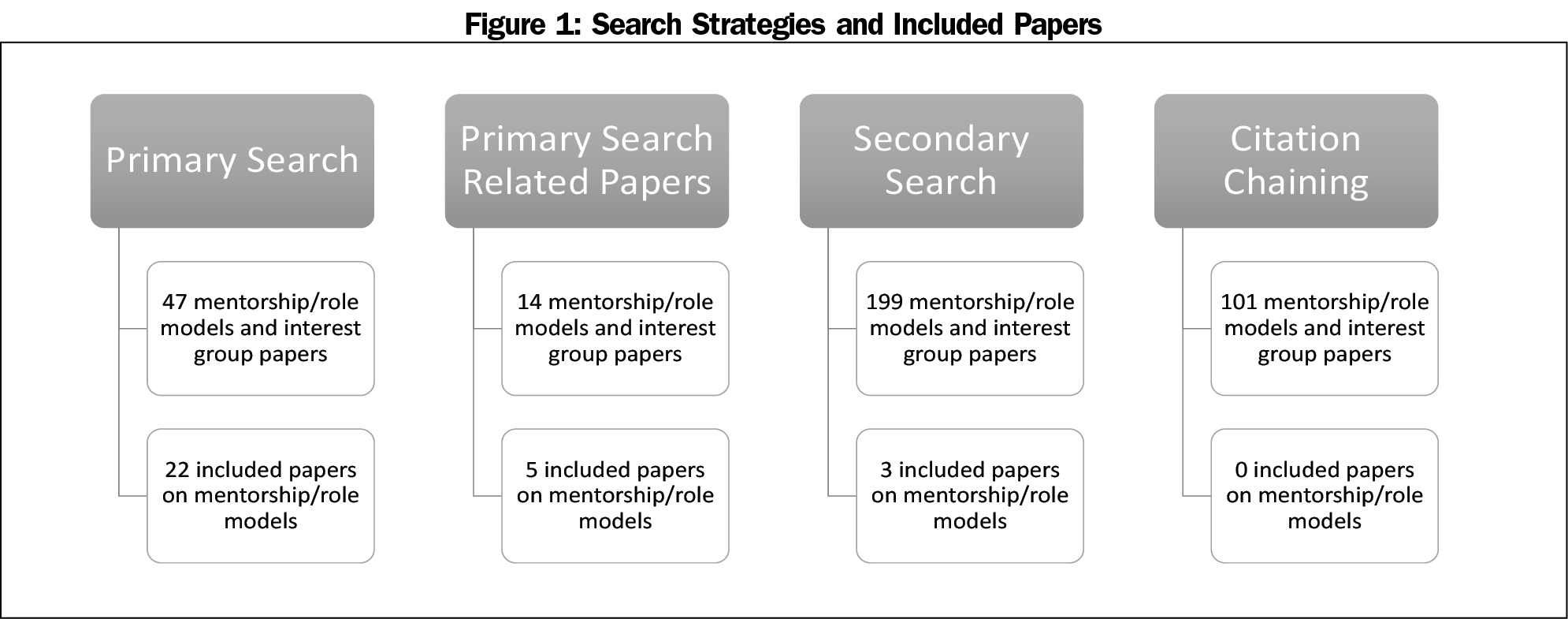

This study used a primary and secondary search (Figure 1). The primary search strategy was performed as part of the scoping review and broadly considered medical school structures, policies, and practices that promote primary care specialty choice.5 A total of 61 manuscripts examining role models and mentors (47 articles meeting the scoping review inclusion criteria and 14 related articles) were identified from this primary search.

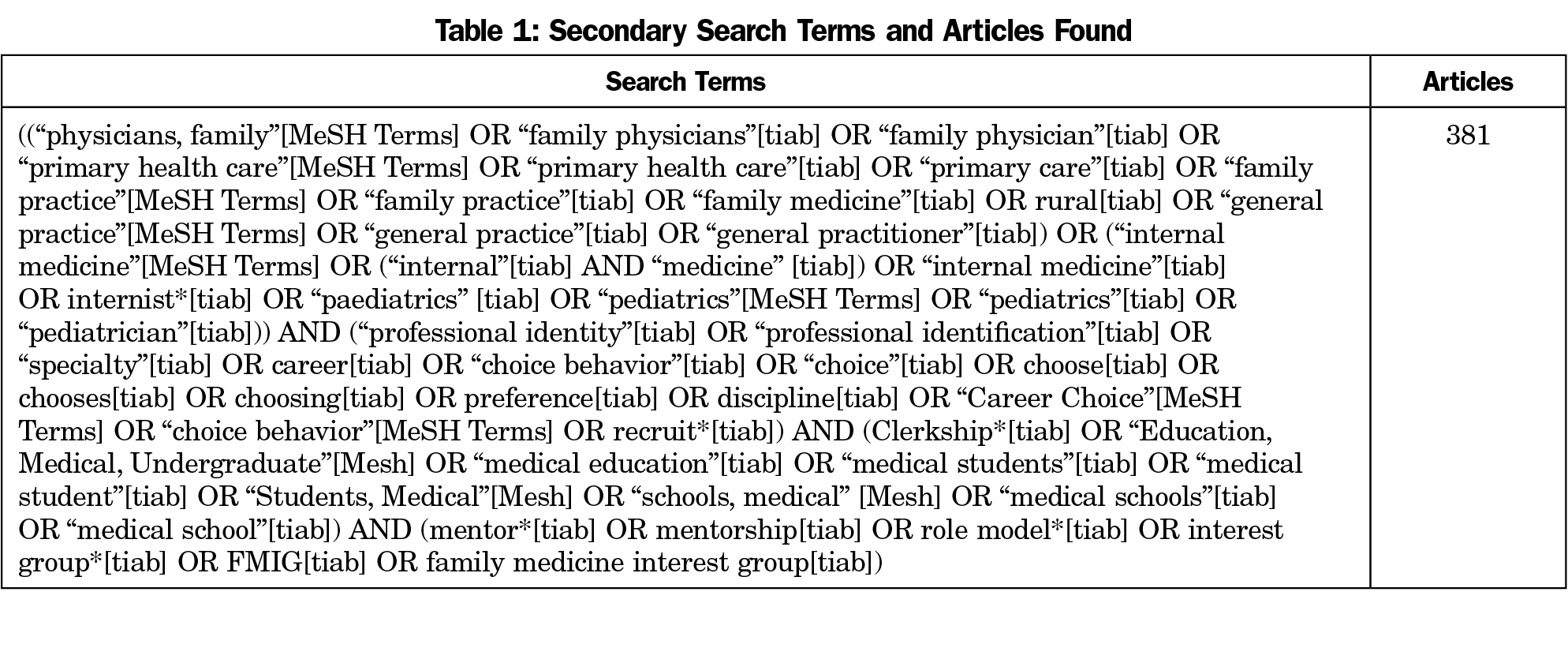

A language mapping process identified key secondary search terms (Table 1) focused on role models and mentoring. Student-run free clinics, and family medicine interest groups were also included in this secondary search and those findings are reported in a separate paper.6 We conducted this search of PubMed, Scopus, and CINAHL on April 13, 2021. This secondary search resulted in 199 additional topic-specific articles.

Two researchers (A.K. and T.S.) evaluated the 61 articles from the primary search and the 199 articles from the secondary search for inclusion. The citations of articles meeting inclusion criteria were then reviewed (citation chaining) to ensure no articles had been missed. In total, titles and abstracts of 362 articles were reviewed (61 from the primary search, 199 from the secondary search, and 101 after citation chaining). Article quality was assessed in the scoping review.

Inclusion criteria for this role model and mentoring study were:

- Articles examined the influence of role models/role modeling or mentors/mentorship in undergraduate medical education on primary care specialty choice,

- Articles published in English, and

- Studies took place in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, or Canada7

We included articles only if they included “role model” or “mentor/mentorship” as either a specific variable in the analysis (for quantitative articles) or as a theme (for qualitative articles). The outcomes of interest were student primary care interest, intention to match to primary care residencies, or entering a primary care career. Primary care careers were defined as family medicine, primary care internal medicine, or primary care pediatrics. We excluded articles if they only examined exposure or contact between faculty, preceptors, and students. Uncertainty about article inclusion was resolved through consensus discussion with one or more additional researchers.

We performed two content analyses. For the first content analysis, each article was reviewed to determine if it included a definition of role model, mentor, or both. This was done by searching each article for the words “role model” and “mentor” and identifying if the authors included a clear definition in the text (for example, “We defined role model as…”).

For the second content analysis we used a stage of intervention rubric described in the scoping review.5 Six categories comprise the intervention rubric: (1) Groundwork, (2) Effectiveness, (3) Impact, (4) Planning, (5) Piloting, and (6) Outcomes. To categorize the quantitative articles, we identified the outcome measures, sample and comparison groups, and role model/mentorship variables. Articles that used qualitative methods or quantitative articles that investigated a single population without comparisons were coded as “groundwork”. Quantitative articles that compared primary care groups vs other groups were coded as either “effectiveness” (examined career intention or interest) or “impact” (examined specialty match or practice). No quantitative of qualitative articles met the intervention stages of planning, piloting, or outcomes as defined by the scoping review.

One researcher (A.K.) performed the two content analyses. This work was iteratively reviewed and reconciled with three other researchers (M.P., J.P., T.S.). The study was determined to be not human subjects research by the Michigan State University Institutional Review Board.

A total of 30 articles met inclusion criteria: the primary search yielded 22 articles, the secondary search yielded 3 articles, and related articles from the primary search yielded five articles. Citation chaining of these articles yielded no additional articles (Figure 1).

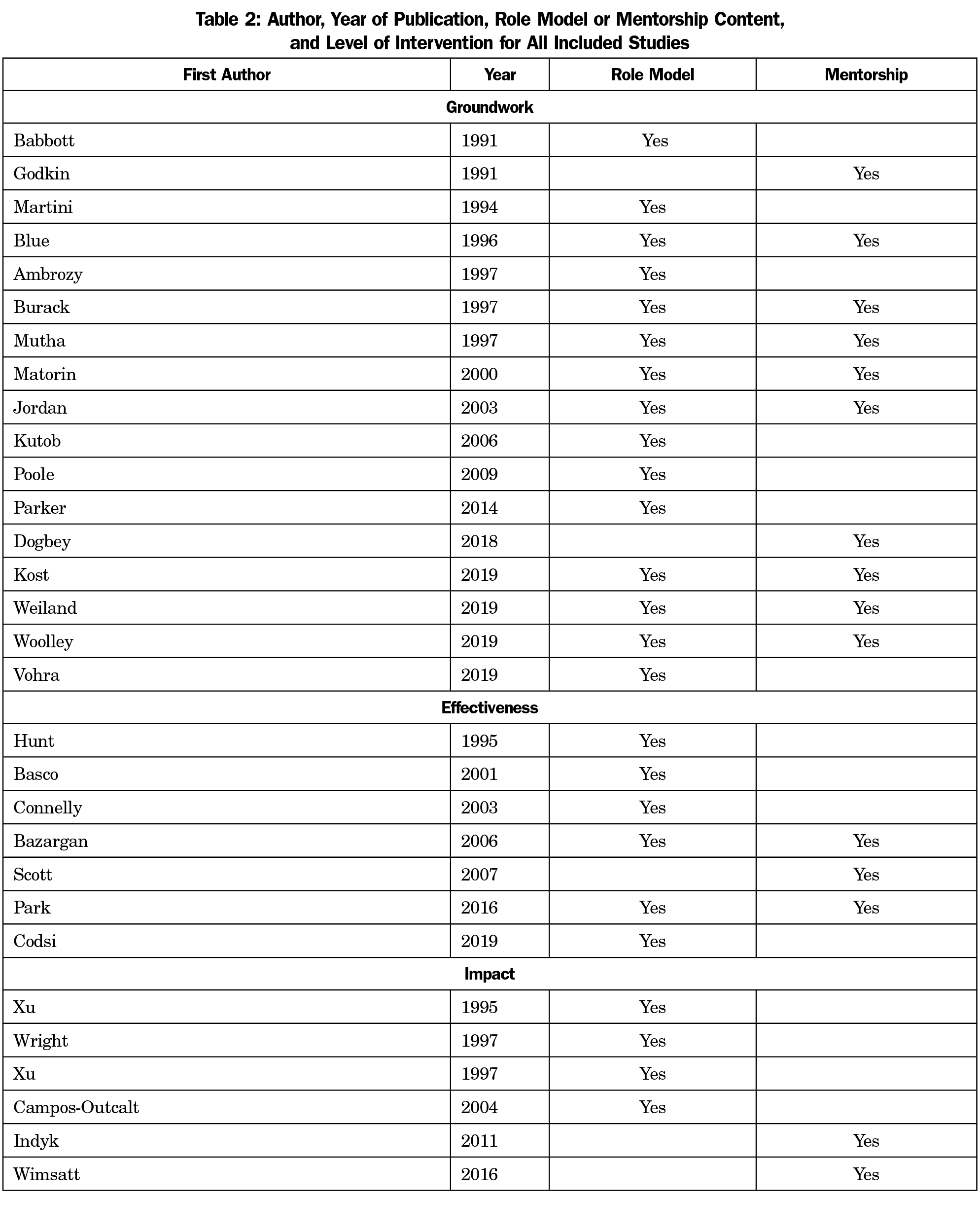

Table 2 shows the counts of articles that examined mentorship, role modeling, or both. It also shows the intervention category as defined by the scoping review. The terms mentorship and role modeling both appear for the first time in the primary care student choice literature in 1991; since that time five articles explored mentorship, 15 articles explored role modeling, and 10 articles explored both.

Three articles on role models offered definitions:

- Basco (1991): “The person should be someone who has influenced the student to choose the same specialty as the role model”8

- Kutob (2006): “individuals admired for their ways of being and acting as professionals”9

- Wright (1997): “a person considered as a standard of excellence to be imitated”10

One article offered a definition of mentors and this was to contrast formal vs informal mentors. Park defined formal mentors as those assigned by a medical school and informal mentors as those sought by students when the formal mentor may not be viewed as an adequate role model.11 Park found that informal mentors were often perceived by students as a more experienced version of themselves.

Three articles offered additional concepts of role modeling and mentorship. Burack discussed the idea that students are “trying on possible selves” through interaction with physicians.12 Ambrozy described three specific domains of role modeling: teaching, personal, and physician.13 Role modeling for teaching included specific behaviors related to bedside teaching and student interaction. Role modeling as a person reflected characteristics such as compassion, enthusiasm, and competence. Role modeling as a physician included patient-centered care and clinical reasoning. Finally, Mutha noted that students in focus groups used the words “mentor,” “role model,” and “advisor” interchangeably.14

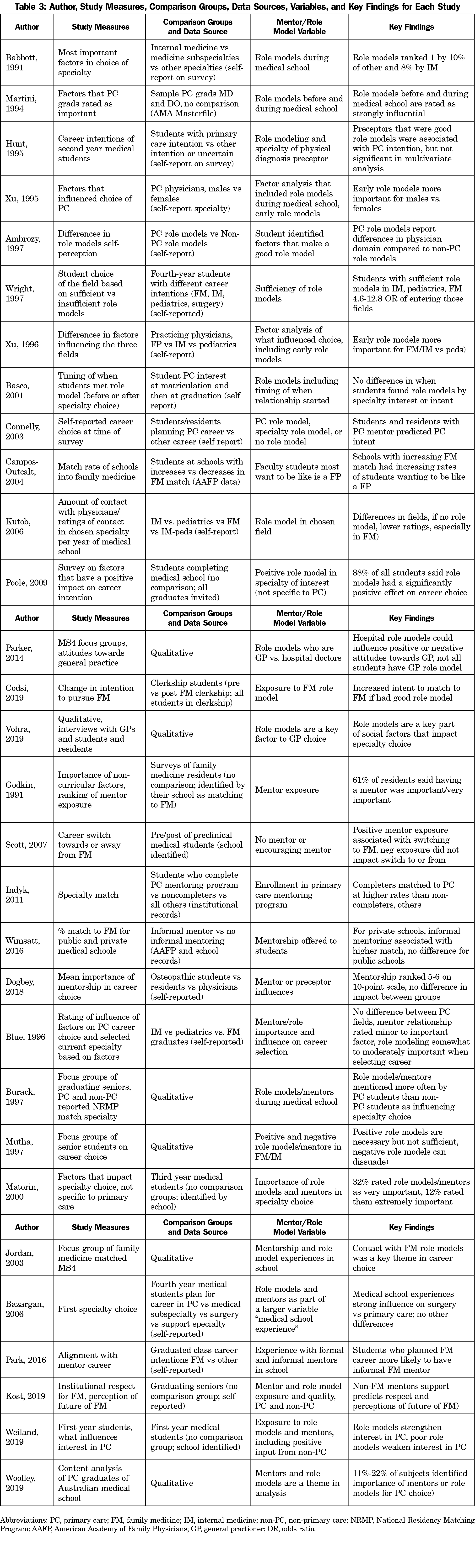

Table 3 shows key findings, outcome measures, population, and role model/mentorship variables. Seventeen articles were groundwork in nature; these sought to understand how role modeling/mentorship influences specialty choice. Seven articles investigated the effectiveness of role modeling/mentorship on primary care career interest or intent. Six articles studied the impact of role modeling/mentorship on actually entering a primary care career.

Groundwork

Multiple articles confirm that medical students, residents, and practicing physicians cite role models and mentors before and during medical school as influential in the choice to pursue a primary care career.1,2,15–21 Articles conflict about the relative importance of role modeling within the primary care specialties and compared to other fields. Some studies have found that role modeling is more important in primary care career choice, and in family medicine in particular.9,22 However, one article found no difference among primary care fields.23 When asked about their own opinions about being role models, primary care physicians report strengths in patient centeredness compared to non-primary care physicians.13

Role models and mentors across practice sites and specialties can be positive or negative in their impact on primary care career interest. Hospital role models could influence either positive or negative attitudes toward general practice.24 Support from mentors who were not in primary care positively influenced students who desired to match into family medicine.25 Two studies found that positive primary care role models are positively influential, but negative primary care role models can weaken student interest.14,26

Effectiveness

Mentorship and role modeling were found to be effective at influencing interest in or intent to enter primary care across different stages of training. Preclinical students who reported positive family medicine mentor exposure were more likely to switch their interest to that field compared to those who did not report positive family medicine mentor exposure, although negative exposure did not impact career intentions.27 However, students’ beliefs that a preclinical preceptor was a good role model was not associated with their career intention.28

Students who planned primary care careers were more likely to report having an informal primary care mentor. Student intent to match in family medicine increased if they had good role modeling during their clerkship.29 However, role modeling in clerkships had a stronger influence on students entering surgical fields than primary care fields.30 The timing of student exposure to role models in the specialty they planned to pursue was not different across fields.8,11,31

Impact

Finally, multiple studies suggest that role models/mentorship impact eventual entry into primary care careers. Students with sufficient role models during medical school had increased odds (OR 4.6-12.8) of matching to primary care specialties compared to other specialties.32 Students who completed a formal mentoring program in primary care were more likely to match to primary care specialties compared to those who did not.33 Private schools with informal mentoring in family medicine had higher match rates to the field than those without informal mentoring.34 Schools with increasing family medicine match rates had increasing rates of students who reported wanting to be like a family physician.35 Practicing primary care physicians’ reports indicate that early role models were more important for family medicine and internal medicine physicians, compared to pediatricians, and that early role models were more important for male than female physicians.36,37

Role models and mentors are widely believed to be essential in helping students choose family medicine and primary care careers. Unfortunately, this review of decades of literature found that the very definitions of these terms were so variable, that the findings could not be synthesized into a consistent, reproducible conceptual model. What can be said is that students clearly have positive and negative experiences with the physicians they work with and learn from, and efforts to facilitate positive experiences in primary care are likely to be beneficial.

Few articles defined role models or mentoring. Clear definitions would allow institutions and departments to provide resources to support the relationships most likely to result in students choosing primary care careers. Lack of specificity in research makes it difficult to replicate or situate within the larger body of literature. It also makes it difficult to know what actionable steps should result from the findings.

The struggle to define the terms role modeling and mentorship is not a new problem.38 The content analysis of definitions in this review and existing literature suggests role models influence who students want to become whereas mentors influence how students get there. This delineation of role modeling and mentorship as two separate constructs is supported by a recent systematic review of role model and mentorship throughout medical education.39

The level of intervention of the studies in this review are low. Many of the articles focused on groundwork, limiting the generalizability of the small number of articles that evaluated the effectiveness or impact of mentorship and role modeling. Those that did evaluate effectiveness or impact did not have robust comparison groups across the educational spectrum from medical student to resident to practicing physicians. Another limitation is that many articles with outcomes of matching into internal medicine or pediatrics did not account for subsequent subspecialization.

Strengths of our study include the systematic nature of the review and the inclusion of work over 30 years. Categorizing the interventions by groundwork, effectiveness, and impact increases understanding of the existing literature and informs future directions.5 Limitations of this study include a lack of search of the grey literature. The search did not include databases such as Cochrane, OVID, MEDLINE, and PsychInfo. This study is limited to role modeling and mentorship. It did not explore advising and similar concepts. Future directions should include multi-institutional studies that investigate the impact of role modeling and mentoring on students’ actual entry into primary care practice.

Role modeling and mentroship during medical school probably matters for primary care career choice. The current literature has laid strong groundwork for conceptualizing how role modeling and mentorship might influence primary care career choice. Future studies should consider how the discipline of family medicine can promote high-quality mentorship and role modeling relationships. The impact of these relationships should also be explored, with a focus on higher levels of the Kirkpatrick pyramid: effectiveness of role modeling and mentorship on student interest or intent in pursuing primary care or the impact of these relationships on actual career choice.40 Understanding the effectiveness and true impact of role modeling and mentorship with clear definitions of the relationships being studied could promote higher-yield interventions that ultimately could lead to a more robust primary care workforce.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: This project was partially supported by a grant from the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) Foundation (J. Phillips, PI), and also partially by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number D54HP23297, “Academic Administrative Units” (C. Morley, PI). This information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by the ABFM, HRSA, HHS, or the US Government.

References

- Babbott D, Levey GS, Weaver SO, Killian CD. Medical student attitudes about internal medicine: a study of U.S. medical school seniors in 1988. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114(1):16-22. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-114-1-16

- Godkin M, Quirk M. Why students chose family medicine: state schools graduating the most family physicians. Fam Med. 1991;23(7):521-526.

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x

- Holden J. Role models in primary care education: inescapable but forgotten? Educ Prim Care. 2013;24(5):308-311. doi:10.1080/14739879.2013.11494193

- Phillips JP, Wendling AL, Young V, et al. Medical school characteristics and practices that support primary care specialty choice: a scoping review. Fam Med. 2022;54(7):Fam Med. 2022;54(7):542-554.

- Sairenji T, Kost A, Young V, Kovar-Gough I, Polverento ME, Morley CPPJ. The impact of family medicine interest groups and student run free clinics on primary care career choice. Fam Med. 2022; 54(7):531-535.

- Wijnen-Meijer M, Burdick W, Alofs L, Burgers C, Ten Cate O. Stages and transitions in medical education around the world: Clarifying structures and terminology. https://doi.org/103109/0142159X2012746449. 2013;35(4):301-307. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2012.746449

- Basco WT Jr, Reigart JR. When do medical students identify career-influencing physician role models? Acad Med. 2001;76(4):380-382. doi:10.1097/00001888-200104000-00017

- Kutob RM, Senf JH, Campos-Outcalt D. The diverse functions of role models across primary care specialties. Fam Med. 2006;38(4):244-251. Accessed September 16, 2019. https://fammedarchives.blob.core.windows.net/imagesandpdfs/fmhub/fm2006/April/Randa244.pdf

- Wright S, Wong A, Newill C. The impact of role models on medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(1):53-56. doi:10.1007/s11606-006-0007-1

- Park JJH, Adamiak P, Jenkins D, Myhre D. The medical students’ perspective of faculty and informal mentors: a questionnaire study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):4. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0526-3

- Burack JH, Irby DM, Carline JD, Ambrozy DM, Ellsbury KESF, Stritter FT. A study of medical students’ specialty-choice pathways: trying on possible selves. Acad Med. 1997;72(6):534-541. doi:10.1097/00001888-199706000-00021

- Ambrozy DM, Irby DM, Bowen JL, Burack JH, Carline JD, Stritter FT. Role models’ perceptions of themselves and their influence on students’ specialty choices. Acad Med. 1997;72(12):1119-1121. doi:10.1097/00001888-199712000-00028

- Mutha S, Takayama JI, O’Neil EH. Insights into medical students’ career choices based on third- and fourth-year students’ focus-group discussions. Acad Med. 1997;72(7):635-640. doi:10.1097/00001888-199707000-00017

- Martini CJ, Veloski JJ, Barzansky B, Xu G, Fields SK. Medical school and student characteristics that influence choosing a generalist career. JAMA. 1994;272(9):661-668. doi:10.1001/jama.1994.03520090025014

- Poole P, McHardy K, Janssen A. General physicians: born or made? The use of a tracking database to answer medical workforce questions. Intern Med J. 2009;39(7):447-452. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2008.01717.x

- Vohra A, Ladyshewsky R, Trumble S. Factors that affect general practice as a choice of medical speciality: implications for policy development. Aust Health Rev. 2019;43(2):230-237. doi:10.1071/AH17015

- Dogbey GY, Collins K, Russ R, Brannan GD, Mivsek M, Sewell S. Factors associated with osteopathic primary care residency choice decisions. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2018;118(4):225-233. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2018.046

- Matorin AA, Venegas-Samuels K, Ruiz P, Butler PM, Abdulla A. U.S. medical students choice of careers and its future impact on health care manpower. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2000;22(4):495-509.

- Jordan J, Brown JB, Russell G. Choosing family medicine. What influences medical students? Can Fam Physician. 2003;49(9):1131-1137.

- Woolley T, Larkins S, Sen Gupta T. Career choices of the first seven cohorts of JCU MBBS graduates: producing generalists for regional, rural and remote northern Australia. Rural Remote Health. 2019;19(2):4438. doi:10.22605/RRH4438

- Burack JH, Irby DM, Carline JD, Ambrozy DM, Ellsbury KE, Stritter FT. A study of medical students’ specialty-choice pathways: trying on possible selves. Acad Med. 1997;72(6):534-541. doi:10.1097/00001888-199706000-00021

- Blue AV, Donnelly MB, Harrell-Parr P, Murphy-Spencer A, Rubeck RF, Jarecky RK. Developing generalists for Kentucky. J Ky Med Assoc. 1996;94(10):439-445.

- Parker JE, Hudson B, Wilkinson TJ. Influences on final year medical students’ attitudes to general practice as a career. J Prim Health Care. 2014;6(1):56-63. Accessed October 14, 2019 doi:10.1071/HC14056

- Kost A, Bentley A, Phillips J, Kelly C, Prunuske J, Morley CP. Graduating medical student perspectives on factors influencing specialty choice: an aafp national survey. Fam Med. 2019;51(2):129-136. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.136973

- Weiland G, Cox K, Sweeney MK, et al. What Attracts Medical Students to Primary Care? A Nominal Group Evaluation. South Med J. 2019;112(2):76-82. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000933

- Scott I, Gowans MC, Wright B, Brenneis F. Why medical students switch careers: changing course during the preclinical years of medical school. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(1):95, 95, 1-5, 94.

- Hunt DK, Badgett RG, Woodling AE, Pugh JA. Medical student career choice: do physical diagnosis preceptors influence decisions? Am J Med Sci. 1995;310(1):19-23. doi:10.1097/00000441-199507000-00007

- Codsi MP, Rodrigue R, Authier M, Diallo FB. Family medicine rotations and medical students’ intention to pursue family medicine: descriptive study. Can Fam Physician. 2019;65(7):e316-e320.

- Bazargan M, Lindstrom RW, Dakak A, Ani C, Wolf KE, Edelstein RA. Impact of desire to work in underserved communities on selection of specialty among fourth-year medical students. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(9):1460-1465.

- Connelly MT, Sullivan AM, Peters AS, et al. Variation in predictors of primary care career choice by year and stage of training. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(3):159-169. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.01208.x

- Wright S, Wong A, Newill C. The impact of role models on medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(1):53-56. doi:10.1007/s11606-006-0007-1

- Indyk D, Deen D, Fornari A, Santos MT, Lu WH, Rucker L. The influence of longitudinal mentoring on medical student selection of primary care residencies. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(1):27. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-11-27

- Wimsatt LA, Cooke JM, Biggs WS, Heidelbaugh JJ. Institution-Specific Factors Associated With Family Medicine Residency Match Rates. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28(3):269-278. doi:10.1080/10401334.2016.1159565

- Campos-Outcalt D, Senf J, Kutob R. A comparison of primary care graduates from schools with increasing production of family physicians to those from schools with decreasing production. Fam Med. 2004;36(4):260-264.

- Xu G, Veloski JJ, Barzansky B, Hojat M, Diamond J, Silenzio VM. Comparisons among three types of generalist physicians: personal characteristics, medical school experiences, financial aid, and other factors influencing career choice. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 1996;1(3):197-207. doi:10.1023/A:1018319914329

- Xu G, Rattner SL, Veloski JJ, Hojat M, Fields SK, Barzansky B. A national study of the factors influencing men and women physicians’ choices of primary care specialties. Acad Med. 1995;70(5):398-404. doi:10.1097/00001888-199505000-00016

- Benbassat J. Role modeling in medical education: the importance of a reflective imitation. Acad Med. 2014;89(4):550-554. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000189

- Radha Krishna LK, Renganathan Y, Tay KT, et al. Educational roles as a continuum of mentoring’s role in medicine - a systematic review and thematic analysis of educational studies from 2000 to 2018. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):439. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1872-8

- Moreau KA. Has the new Kirkpatrick generation built a better hammer for our evaluation toolbox? Med Teach. 2017;39(9):999-1001. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2017.1337874

There are no comments for this article.