The COVID-19 pandemic created challenges to recruitment for residency programs. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), as a member of the Coalition for Physician Accountability, encouraged residency programs to transition to virtual interviewing in May 2020.1 The academic family medicine community followed this recommendation.2 The transition from in-person visits led to creative recruitment practices. While there has been discussion regarding approaches that are most engaging,3-5 there is minimal research that examines the impact virtual interviews have had from the applicant’s perspective. Our study investigates the impact this transition had on applicants’ interview experiences and decisions in applying with a family medicine department at a large research university.

BRIEF REPORTS

The Impact of Virtual Interviews on the Resident Candidate: A Before-and-After Comparison

Thomas Bishop, PsyD | Laura Lee, MD | Jenna B. Greenberg, MD | Rudy Wenner, MD | Wendy Furst, MA | Jean Wong, MD

Fam Med. 2022;54(10):833-835.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2022.510274

Background and Objectives: A significant impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family medicine residency recruitment has been a requested transition to virtual interviewing by the Association of American Medical Colleges and the academic family medicine community. This has led to creative and adaptive approaches to virtual interviewing with little previous knowledge, experience, or processes. This work describes the impact of transitioning to virtual recruitment on applicants’ reported experiences and factors influencing decision-making with family medicine at a large research university.

Methods: We made a comparison of 2 years of in-person interview day surveys with 2 years of virtual interview surveys following transition to virtual recruitment. We tested differences between in-person and virtual interviews for significance using χ2 tests.

Results: There were significant differences in factors influencing a candidate’s decision to apply. Candidates who participated in virtual interviews were more interested in urban training settings, a community setting, and obstetrical training compared with the in-person interview cohort. Nearly 50% of virtual candidates reported preferring virtual interviews in the future. There were no significant differences in how candidates rated their experience of the interview process and they indicated adequate contact with resident personnel despite a transition to virtual interviews.

Conclusions: The transition to virtual recruitment has been well received by candidates, as indicated by the high positive ratings of the cohorts. The transition has not resulted in a negative impact on the recruitment experience or the ability to meet with resident leadership.

Our program recruits 13 interns per year, matching them into two continuity clinics. During the 2020-2021 and 2021-2022 seasons, all interviews were held virtually with all prior interviews being in-person. Each interviewee was invited to join an informal, resident-led/resident-only informal virtual get-together prior to their interview. Interview days were structured with opening introductions, five 20-minute one-on-one interviews with faculty and residents, followed by filmed virtual tours and open discussion with residents. Our local graduate medical education (GME) office created virtual content about our community, and residents increased content posted to social media. Following interviews, a virtual second-look event was held in conjunction with our GME community.

Candidates voluntarily completed a postinterview survey as part of an internal quality improvement effort, with questions specific to their perceptions of their interview experience. Applicants who completed virtual interviews were asked if national ranking, social media, or prior experiences at the institution influenced their decision to apply. These residents were additionally asked about their preferences for in-person or virtual interviews. We examined survey results for trends across the pre- and postvirtual interviewing recruitment cycles. We combined recruitment cohorts 2018-2019 and 2019-2020 to form the in-person interview group, and we combined 2020-2021 and 2021-2022 to form the virtual interview group.

We conducted statistical analyses using SPSS Statistics software, version 26 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). We tested differences between applicant years for significance using χ2 tests for all survey questions.

Our institutional review board policies do not require approval for postinterview data that is for quality improvement, and our study also falls outside of Common Rule and Food and Drug Adminsitration definitions of research.6

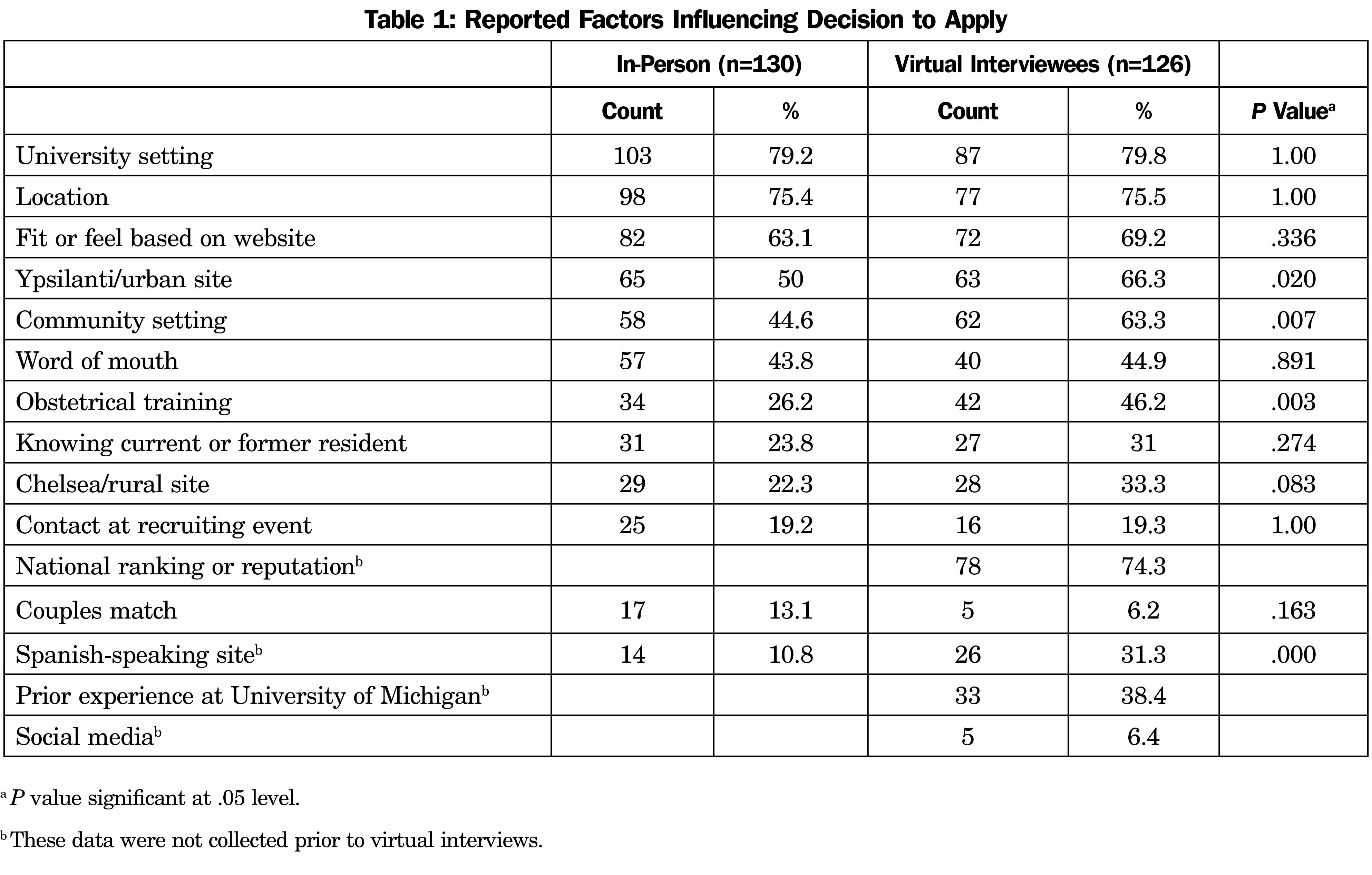

Five hundred twelve interviews were conducted over 4 years (2018-2019: n=124, 2029-2020: n=131, 2020-2021: n=129, 2021-2022: n=128). The total number of surveys collected over 4 years was 256 (2018-1019: n=70; 2019-2020, n=60; 2020-2021, n=78; 2021-2022, n=48). We examined demographic and geographic data between cohorts. The only significant difference found was an increase in Hispanic applicants, which coincided with the creation of a Spanish language track. The top factors influencing an applicant’s decision to apply across all 4 years included university setting, location, fit, and feel based on the program website. Among residents who completed a virtual interview, national ranking was the second-most selected factor (74.3%; Table 1). The number of applicants who selected an urban site significantly increased from 50% (in-person) to 66.3% (virtual) as a factor influencing one’s decision to apply, as did community setting, with an increase from 44.6% to 63.3%.

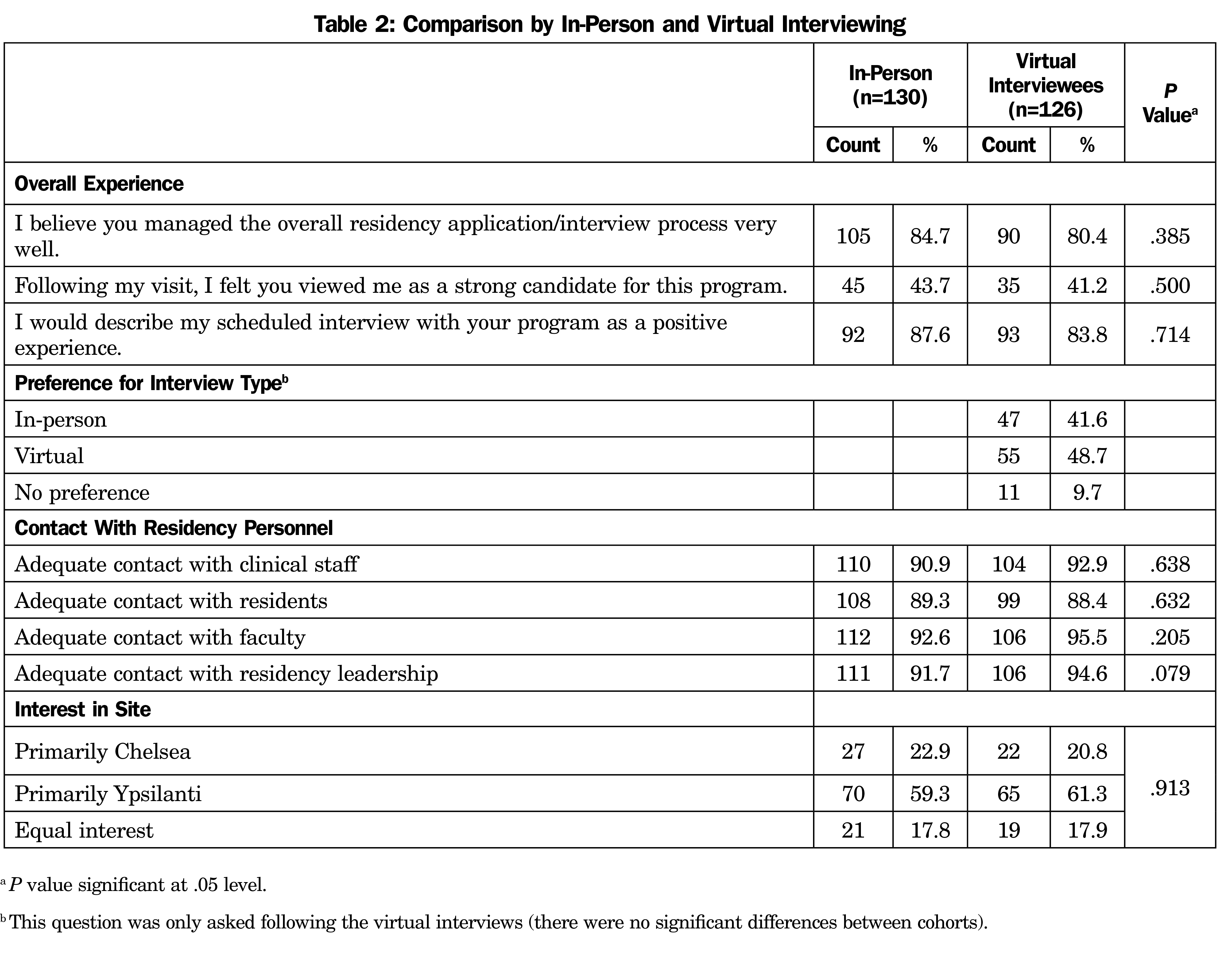

Outside of the pandemic, 48.7% of the virtual applicants indicated a virtual interview as their preference and 41.6% indicated preference for an in-person interview (this question was not asked of in-person applicants). We found no significant differences in candidate perceptions of the management of the interview process. Both in-person and virtual interview candidates reported that the process was managed very well (84.7% and 80.4%, respectively). Similarly, 87.6% of the in-person interview candidates and 83.8% of the virtual candidates described their interview as a positive experience.” Candidates from both in-person and virtual cohorts did not perceive themselves to be strongly evaluated after the interview (43.7% and 41.2%, respectively; Table 2).

Both groups reported adequate contact with clinical staff, residents, faculty, and residency leadership. No significant differences were identified.

There were no significant differences in how applicants—both in-person and virtual interviewees—characterized their experience, suggesting that the virtual model of recruitment was neither superior nor inferior, and as effective as in-person recruitment. Candidates from the virtual interviews expressed more interest in an urban clinic, suggesting a potential change in how sites are portrayed within the virtual process. Candidates from virtual interviews expressed more interest in obstetrics training. Perhaps these changes are a result of a larger candidate pool due to fewer financial and time restrictions.7 This could also reflect a change in applicant interests.

Over half of applicants in all years did not feel they were assessed as a strong candidate. Candidates perceived positively may have been inadvertently provided with indirect feedback. Our residency has attempted to reduce bias by standardizing interview questions, which may have resulted in less feedback to applicants. Future research may track candidates’ ratings by the recruitment team to determine accuracy in candidate perceptions.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is that it reflects the experience of a single site, which impacts generalizability, and results may be more applicable to large academic programs as compared to community-based programs. Study findings represent a small number of candidates responding to unvalidated surveys that were constructed for the purpose of feedback. There was also no way to contact applicants who only considered programs offering in-person interviews, potentially skewing the data. Future research may also benefit from comparing how our program rated candidates and applicants’ perception of being viewed strongly.

It is possible to conduct a virtual interviewing process that is as equivalent to in-person interviewing in terms of reported applicant experience and factors leading to decisions in applying to our program. Advantages of a virtual recruitment process include saving costs of travel and lodging. However, virtual-only options limit how applicants adequately learn about programs. Looking to the future, we need to carefully consider how this could impact the size and diversity of our applicant pool.

References

- Specialty Response to COVID-19. Association of American Medical Colleges. Accessed November 13, 2020. https://students-residents.aamc.org/applying-residency/article/specialty-response-covid-19/

- Cullen JA, Brown SR, DeLuca RC, Clements DS, Perkins RA, Westfall J, Elliot T. Letter to our Family Medicine community: COVID-19 impacts to 2020-2021 residency interview process. May 29, 2020. Accessed October 4, 2022. https://www.stfm.org/media/2876/covid-academic-fm-ltr-fnl.pdf

- Bhardwaj P, Kleiber GM, Baker SB, Fan KL. Applying to Residency in the COVID-19 Era: Virtual Interview Tips for Success. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;9(1):e3389. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000003389

- Buonpane C, Young S, Tuliszewski R, et al. Do’s and don’ts of the virtual interview: perspectives from residency and fellowship applicants. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(6):671-673. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-20-00518.1

- Patel TY, Bedi HS, Deitte LA, Lewis PJ, Marx MV, Jordan SG. Brave new world: challenges and opportunities in the COVID-19 virtual interview season. Acad Radiol. 2020;27(10):1456-1460. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2020.07.001

- University of Michigan Human Research Protection Program. Operations Manual. January 2022. . Accessed January 28, 2022. http://research-compliance.umich.edu/operations-manual-part-4#authority

- Asaad M, Rajesh A, Kambhampati PV, Rohrich RJ, Maricevich R. Virtual interviews during COVID-19: the new norm for residency applicants. Ann Plast Surg. 2021;86(4):367-370. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000002662

Lead Author

Thomas Bishop, PsyD

Affiliations: Department of Family Medicine, Michigan Medicine, Chelsea

Co-Authors

Laura Lee, MD - Department of Family Medicine, Michigan Medicine, Chelsea

Jenna B. Greenberg, MD - Department of Family Medicine, Michigan Medicine, Chelsea

Rudy Wenner, MD - Department of Family Medicine, Michigan Medicine, Chelsea

Wendy Furst, MA - Department of Family Medicine, Michigan Medicine, Chelsea

Jean Wong, MD - Department of Family Medicine, Michigan Medicine, Chelsea

Corresponding Author

Thomas Bishop, PsyD

Correspondence: Department of Family Medicine, Chelsea Health Center, 14700 E. Old US 12, Chelsea, MI 48118. 734-475-4487.

Email: Thomasbi@med.umich.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.