Background and Objectives: The COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to burnout among residents, a population already at increased risk for heightened stress and work-related fatigue. Residency programs were also forced to alter schedules and educational objectives. We assessed how social distancing restrictions (specifically self-isolation) enacted early in the COVID-19 pandemic affected family medicine (FM) resident well-being and burnout. Our FM department created a 2-week reserve rotation as a response to the need to socially distance and protect the residents. We explored how the reserve rotations impacted their experiences.

Methods: A purposive sample of FM residents were recruited in May and June of 2020. Qualitative interviews explored well-being and burnout, changes in education and provision of patient care, and overall adaptation to the pandemic. We employed interpretative phenomenology to analyze the interviews.

Results: We interviewed six out of 24 residents before saturation was reached. Qualitative analysis revealed themes related to positive and negative consequences of the pandemic, including uncertainty/fear of the unknown, schedule/life changes, communication, and adapting to a new routine.

Conclusions: The COVID-19 pandemic placed an additional burden on residents, a group already at increased risk for burnout. While uncertainty and disruptions in work and home life were significant stressors, this cohort demonstrated adaptability and resilience that was facilitated by peer support and effective communication. These factors, along with the reserve rotation with decreased clinical responsibilities, led to an improved sense of well-being and decreased feelings of burnout.

Clinicians face increased stress from the COVID-19 pandemic, including risk of infection, disrupted schedules, and alterations in work/home life.1 Prepandemic research suggests residents suffer from greater burnout than other clinicians.2,3 COVID-19 caused alterations in resident rotations, changes in patient care, quarantine, and disruptions in education by forcing online didactics. Research suggests these changes negatively affected resident well-being.3-7 Alterations or cancelations of elective rotations were particularly linked to burnout and reduced well-being.8

These challenges have fueled interest in addressing resident burnout. However, effective strategies to reduce burnout remain elusive. While previous studies suggest that social and institutional support bolster resident well-being, some interventions including faculty mentorship and counseling were insufficient.7 It is critical to identify interventions that effectively mitigate burnout and enhance well-being.3

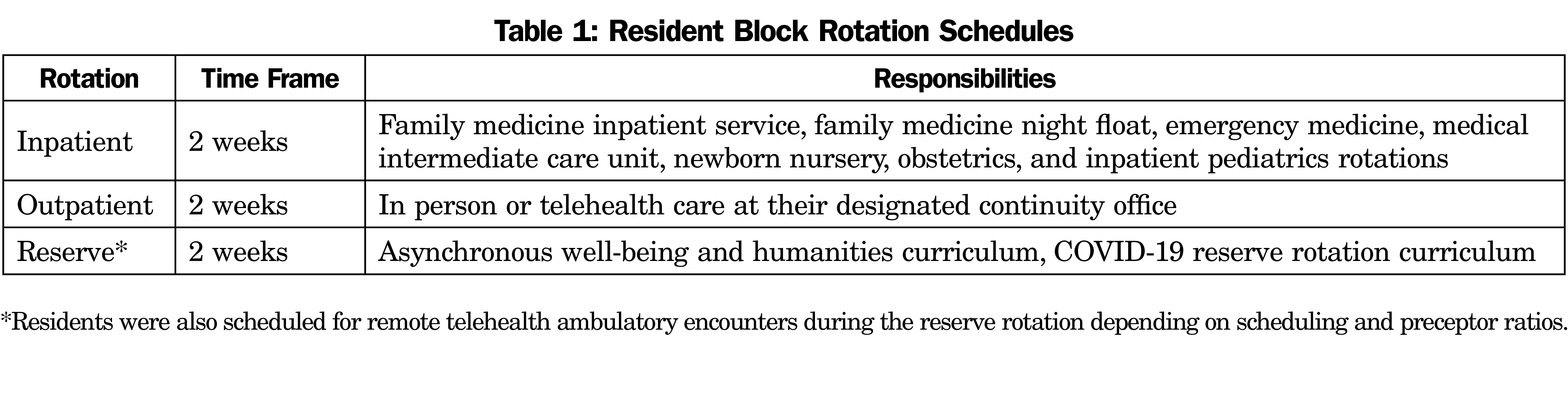

We created a 2-week reserve rotation that included an asynchronous independent study curriculum at the start of the pandemic to protect our family medicine (FM) residents from infection, consistent with social distancing (specifically self-isolation recommendations). We sought to explore resident perceptions of this intervention, particularly regarding its effects on well-being and feelings of burnout.

This study (STUDY#00015096) received institutional review board approval.

Participants

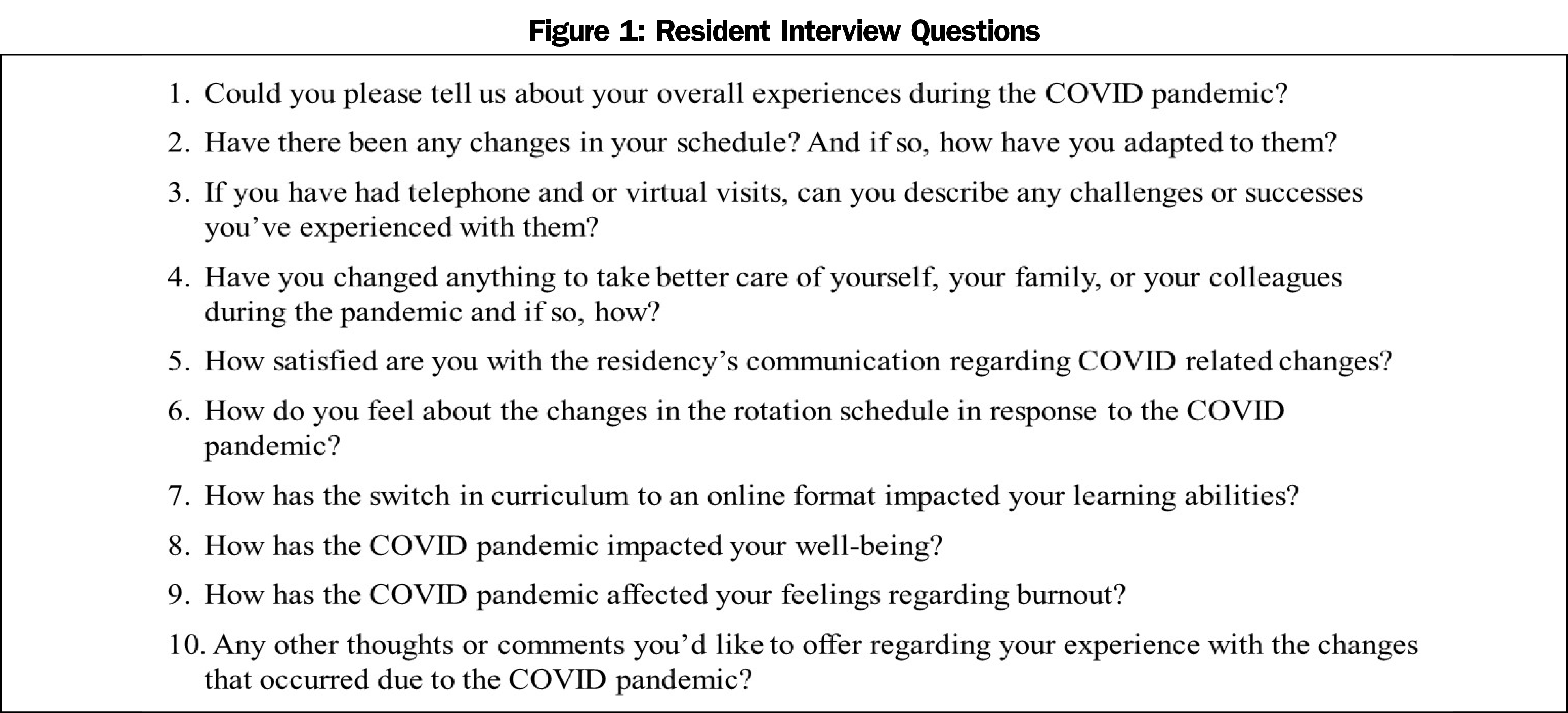

All FM residents at our university hospital were invited to complete an interview about their motivation or ability to meet residency requirements, well-being, feelings of burnout, and general experiences during the pandemic (Figure 1).

Procedures

In March 2020, the FM residency program implemented an asynchronous curriculum and block rotations (Table 1) in a platoon system to limit potential transmission of COVID-19 between residents, allowing for quarantine after hospital exposure, and to focus on resident education and well-being. All FM residents (n=24) were invited to complete voluntary interviews in May 2020.

Analysis

We used interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) to analyze the interviews. IPA uses purposive sampling to enhance insight into an experience by selecting participants for whom the research is meaningful. This helps to conceptualize the human experience and focuses on perceptions of research participants and how they make sense of an experience.9 Interviews were analyzed by three team members (J.P., C.L., E.M.), and emerging themes for each participant were condensed to develop superordinate themes for further discussion. Saturation of the data began around the fifth interview, and we felt no new significant themes would be discovered after analysis of the sixth interview. We employed a consensus approach until study team members reached 100% agreement on themes.

Six of 24 residents completed interviews before saturation was reached. Three were PGY3s, three were PGY2s, and two were male. Five were more than 30 years old, and four were partnered but only one had children. Twenty-two residents completed the reserve rotation from April 1 through June 30, 2020. Two had vacation scheduled that reduced their clinic and telehealth responsibilities, however they still had to self-isolate at home due to travel restrictions at the time.

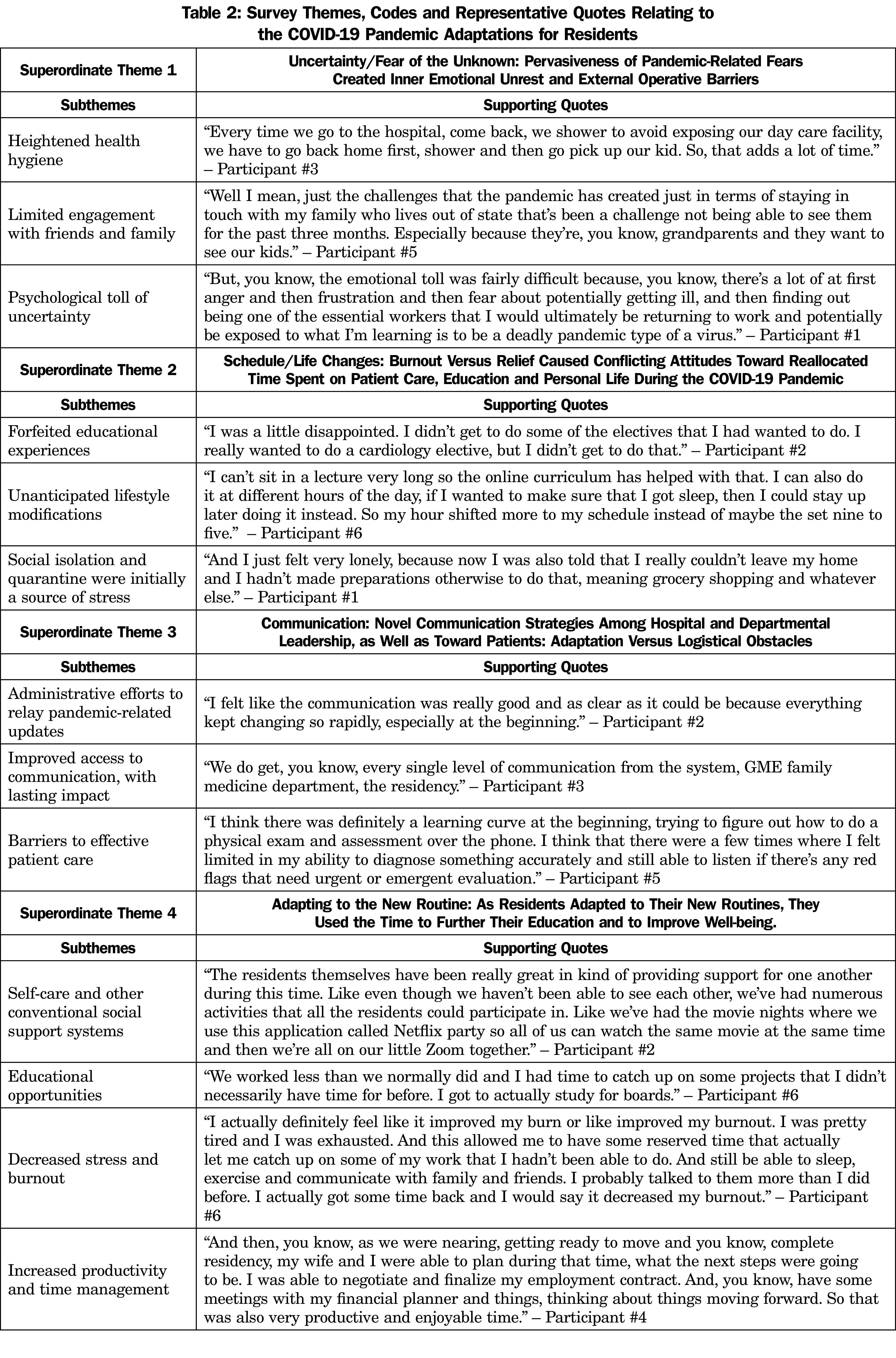

The pandemic and associated disruptions had a meaningful impact on these residents. Table 2 displays a list of superordinate themes, subthemes, and supportive quotes. Themes from early in the pandemic included uncertainty and fear of the unknown. There were frequent changes to institutional policy and procedures as the pandemic evolved. Most residents noted the reserve rotation was initially stressful, as the psychological toll of uncertainty and limited engagement with family and colleagues increased apprehension.

Some initial conflicting attitudes were reported as schedule and life changes reallocated time spent on patient care, medical education, and personal life. Indicators of increased potential burnout were noted as residents lamented about forfeited educational experiences and elective rotations, unanticipated lifestyle changes, and stress from social isolation while completing the reserve rotation.

To address the uncertainty and frequent schedule changes, department and residency leadership adopted novel communication strategies. The residents praised administrative efforts to provide timely pandemic-related updates, which kept everyone informed of the latest recommendations.

As the residents adapted to new routines, many used the time on the reserve rotation to further their education and improve self-care and well-being. Some studied for board exams. Others embraced the opportunity for reduced commute time, as in-person didactic sessions were replaced by Zoom meetings or asynchronous learning. Several developed lifestyle routines that increased productivity, improved their diets or opportunities for exercise, or developed support systems including virtual dinners and movie/game nights via Zoom. All participants mentioned increased communication with family, friends, and colleagues.

This study highlights the experiences of FM residents and their feelings of burnout and well-being as they navigated unprecedented challenges early in the pandemic. While uncertainty and disruptions in work and home life were significant obstacles, this cohort demonstrated adaptability and resilience during this stressful period.

The reserve rotation and related schedule disruptions were of particular interest regarding resident well-being. Historically, alterations in schedules have been associated with increased burnout.4,6,8 Therefore the reserve rotation might be expected to worsen symptoms of burnout, and was initially a source of stress from social isolation. However, as residents adapted to new routines they reported feeling rejuvenated and “ready to get back on the treadmill,” with improved well-being and decreased feelings of burnout. Given the known positive correlation between work hours and burnout,10 one potential source of improved well-being may have been the decreased clinical workload, as seen in residents’ stated appreciation of more time for self-care and social connection. This may suggest value in scheduled downtime to improve resident well-being and burnout.6

Uncertainty and fear of the unknown were prevalent themes in these interviews, in addition to isolation from friends and family. These findings corroborate research on the negative influence of the pandemic on wellness, burnout, and career satisfaction among residents in other specialties.8,11 Residents relied upon their social networks to adapt to these challenges, especially support between residents, which has previously been associated with reduced burnout.12

Communication was a significant issue, generating negative and positive responses. Some mentioned an initial email/communication overload was burdensome. This improved with development of a concise, daily COVID-19 brief that residents found beneficial. Concise, consistent, organizational communication may be valuable for residents under similar circumstances.

Limitations included a small sample in a specific residency, which may impact generalizability.

The pandemic placed additional burdens on residents, and while uncertainty and disruptions in work and home life were significant stressors, this cohort demonstrated adaptability and resilience facilitated by peer support, effective communication, and a reserve rotation with decreased clinical responsibilities. Further study might explore scheduled downtime, facilitating social connectivity, and the use of reserve rotations as interventions to improve resident well-being and reduce burnout, especially during times of increased stress.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Dr Eric Messner was supported by the Inter-professional Education Incentive Award (Office of Inter-professional Collaborative Education and Teamwork): The Longitudinal Interfacing of Interdisciplinary Learners with Patients to Improve Transitions of Care.

Presentations: This research was presented in poster format at the 2022 STFM Annual Spring Conference in Indianapolis Indiana, April 30-May 4.

References

- Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):510-512. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2008017

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among US medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general US population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-451. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134

- Ellinas H, Ellinas E. Burnout and protective factors: are they the same amid a pandemic? J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(3):291-294. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-20-00357.1

- Coleman JR, Abdelsattar JM, Glocker RJ, et al; RAS-ACS COVID-19 Task Force. COVID-19 pandemic and the lived experience of surgical residents, fellows, and early-career surgeons in the American College of Surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;232(2):119-135e20. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.09.026

- Lie JJ, Huynh C, Scott TM, Karimuddin AA. Optimizing resident wellness during a pandemic: University of British Columbia’s General Surgery program’s COVID-19 experience. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(2):366-369. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.07.017

- Wietlisbach LE, Asch DA, Eriksen W, et al. Dark clouds with silver linings: resident anxieties about COVID-19 coupled with program innovations and increased resident well-being. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(4):515-525. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-20-01497.1

- Zoorob D, Shah S, La Saevig D, Murphy C, Aouthmany S, Brickman K. Insight into resident burnout, mental wellness, and coping mechanisms early in the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):e0250104. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0250104

- Khalafallah AM, Lam S, Gami A, et al. A national survey on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic upon burnout and career satisfaction among neurosurgery residents. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;80:137-142. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2020.08.012

- Smith JA, Flowers P, Larkin M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2009.

- Balch CM, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye L, et al. Surgeon distress as calibrated by hours worked and nights on call. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(5):609-619. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.06.393

- Chou DW, Staltari G, Mullen M, Chang J, Durr M. Otolaryngology resident wellness, training, and education in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2021;130(8):904-914. doi:10.1177/0003489420987194

- Ziegelstein RC. Creating structured opportunities for social engagement to promote well-being and avoid burnout in medical students and residents. Acad Med. 2018;93(4):537-539. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002117

There are no comments for this article.