The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic threatened all aspects of academic family medicine (FM),1 constituting a crisis.2 It prompted multiple research articles on leadership,1, 3 FM management,4,-9 academic pivots,10,-12 and lessons learned,13-19 but few have examined how these responses arose.20 Our objective was to gain insight into the context and nature of FM leaders’ discussions to address a crisis.

BRIEF REPORTS

COVID-19: A Qualitative Analysis of Academic Family Physician Leaders’ Crisis Response

David G. White, MD, CCFP, FCFP | Mary Ann O'Brien, PhD | Sylvie D. Cornacchi, MSc | Risa Freeman, MD, MEd, CCFP, FCFP | Eva Grunfeld, MD, DPhil, CCFP, FCFP

Fam Med. 2023;55(1):38-44.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.55.421082

Background and Objectives: The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic severely threatened all aspects of academic family medicine, constituting a crisis. Multiple publications have identified recommendations and documented the creative responses of primary care and academic organizations to address these challenges, but there is little research on how decisions came about. Our objective was to gain insight into the context, process, and nature of family medicine leaders’ discussions in pivoting to address a crisis.

Methods: We used a qualitative descriptive design to explore new dimensions of existing concepts. The setting was the academic family medicine department at the University of Toronto. To identify leadership themes, we used the constant comparative method to analyze transcripts of monthly meetings of the departmental executive: three meetings immediately before and three following the declaration of a state emergency in Ontario.

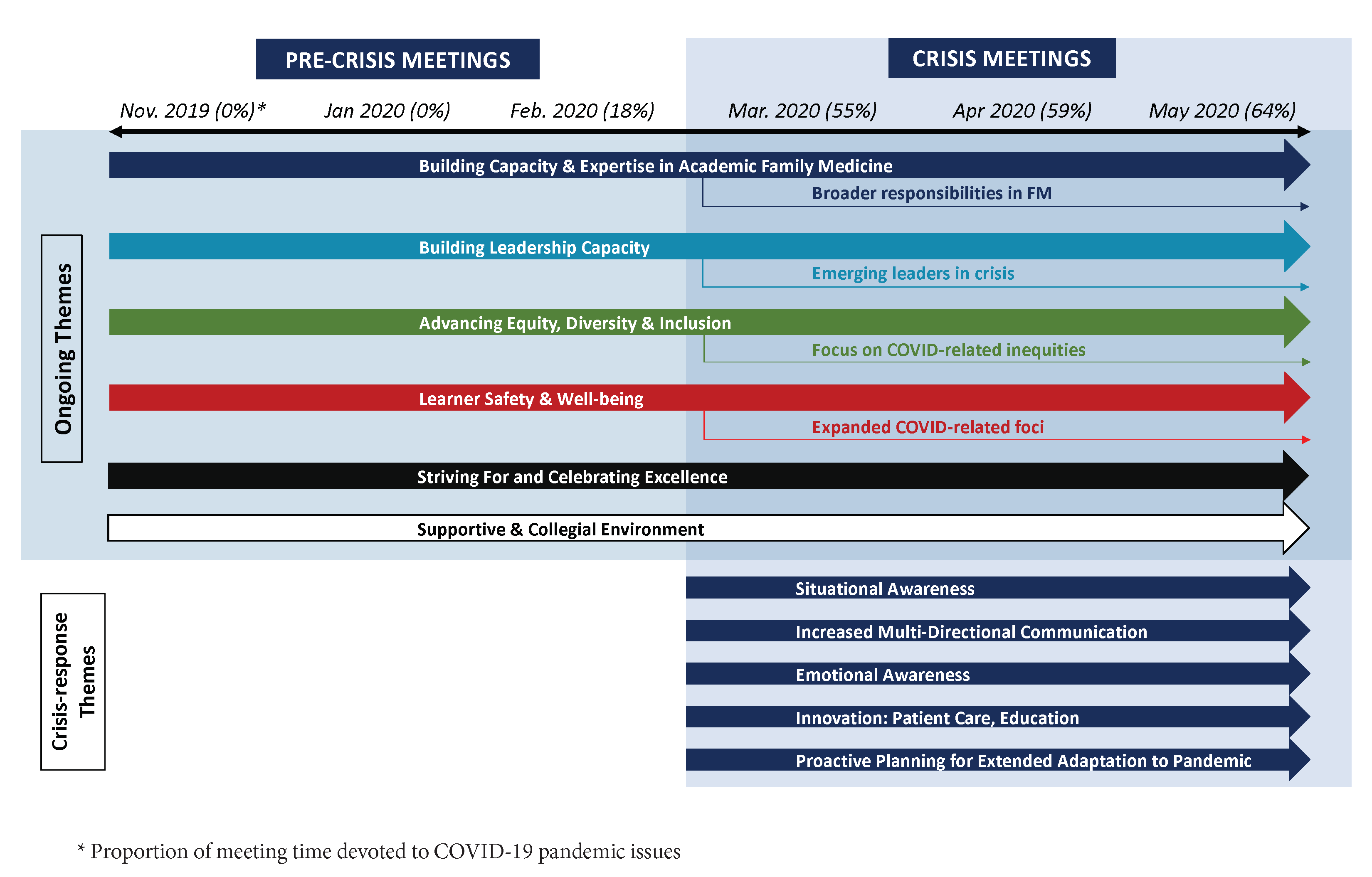

Results: Six themes were evident before and after the onset of the pandemic: building capacity in academic family medicine; developing leadership; advancing equity, diversity, and inclusion; learner safety and wellness; striving for excellence; and promoting a supportive and collegial environment. Five themes emerged as specific responses to the crisis: situational awareness; increased multidirectional communication; emotional awareness; innovation in education and patient care; and proactive planning for extended adaptation to the pandemic.

Conclusion: Existing cultural and organizational approaches formed the foundation for the crisis response, while crisis-specific themes reflected skills and attitudes that are essential in clinical family medicine, including adapting to community needs, communication, and emotional awareness.

Design

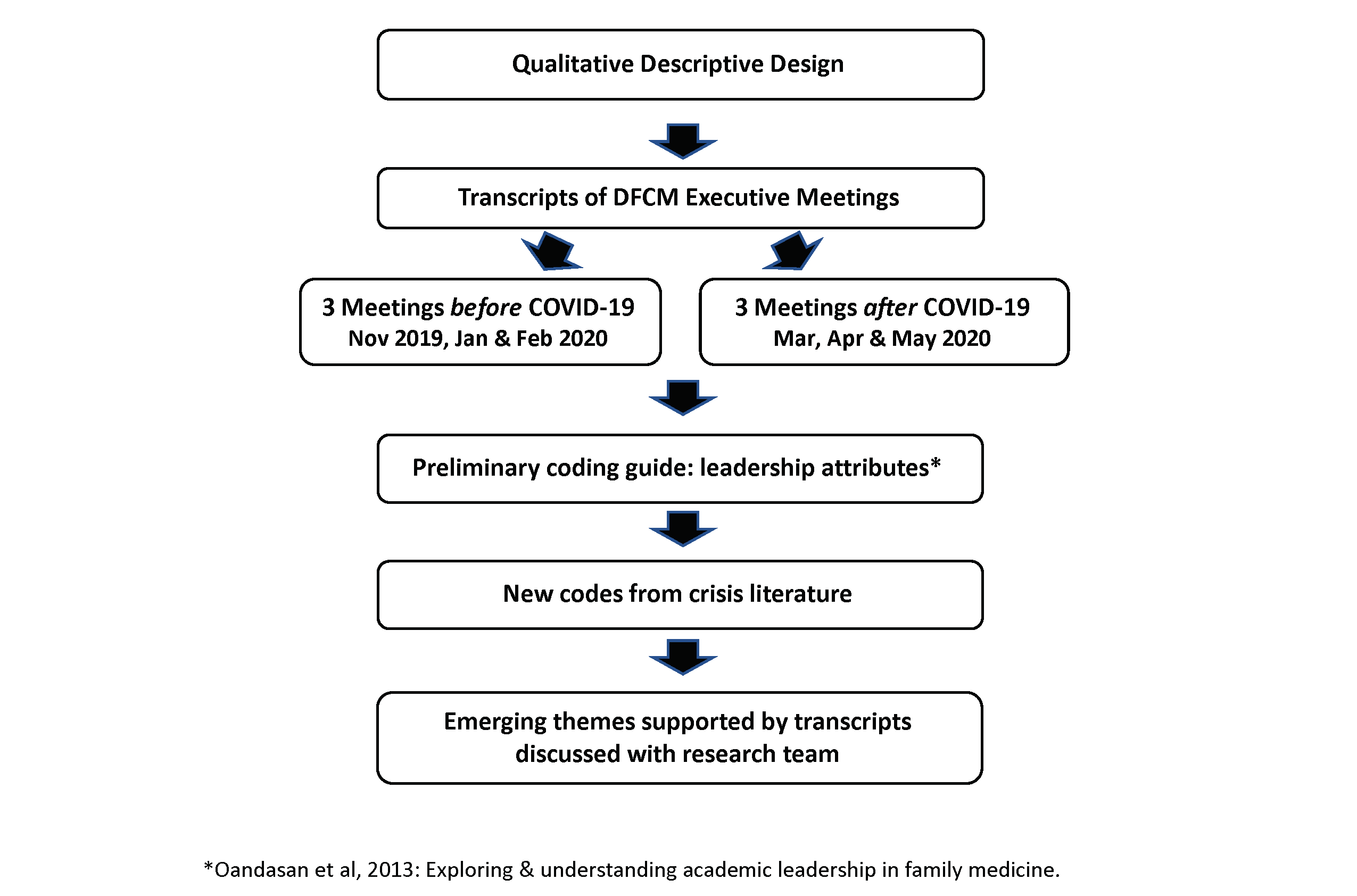

We used a qualitative descriptive design, which is appropriate to understand a phenomenon within its context.21

Setting

The Department of Family and Community Medicine (DFCM) at the University of Toronto uses a distributed academic model,22 with over 1,900 faculty at 14 hospital sites and multiple community practices. Monthly executive meetings include the chair, academic programs leaders, hospital site chiefs and senior staff. Meetings are forums for exchanging information, formulating policy, and coordinating action.

Data Collection

From a sampling frame of recordings of monthly executive meetings, we purposively sampled23 six: three meetings before Ontario declared a state emergency in March 2020 and three afterward (Figure 1). All attendees (median 33, range 30-36) consented and the University of Toronto provided ethics approval.

Data Analysis

The coding guide was informed by three dominant attributes of effective leadership: a vision, enabling others to succeed, and excellence in an area. 24 We identified additional attributes from crisis leadership literature. 25-33

We used the constant comparative method.34-36 Two researchers who were not members of the executive committee and did not attend meetings independently coded transcripts. They assigned codes to leadership behaviors and compared codes within and across transcripts. Major themes with supporting quotes were then developed and discussed with the team. To reduce the potential for errors in data interpretation, three research team members who were on the executive committee checked the deidentified quotes against the themes.37 We maintained study rigor through a systematic record of codes and memos, using data management software and research team expertise.37-39 We addressed member checking through a presentation and discussion of our findings with the executive in December 2021.37

Figure 2 presents an overview of the themes and timeline.

Six Themes Present in All Meetings (Appendix Table A)

See Appendix Table A for descriptions with exemplar supporting quotes, of the following six major themes.

Building capacity and expertise in academic FM was a focus of all meetings. After pandemic onset, everyone demonstrated eagerness to help through expanded clinical roles and broader responsibilities in response to community needs, despite uncertainty. Table 2 lists examples.

Building leadership capacity in FM was evident in many examples of nurturing and supporting leaders and identifying rising stars. During the crisis, we noted the emergence of new leaders among front-line staff.

Commitment to advancing equity, diversity,and inclusion (EDI) was evident in all meetings. An equity lead was appointed in January 2020 and an EDI retreat was planned. During the pandemic, we noted advocacy for vulnerable populations.

The executive consistently took responsibility for learner safety and well-being. During the crisis, concerns centered on emotional well-being, physical safety, and supporting attainment of competency.

All meetings had examples of striving for and celebrating excellence, including encouragement to apply for awards, grants, and promotion, and a standing agenda item recognizing recipients. As the crisis unfolded, recognition focussed on successes in improving virtual care and education.

A supportive and collegial environment was evident in frequently expressed appreciation for the ideas, contributions and expertise of faculty, residents, and learners, and included respectful voicing of disagreement or concerns.

Five Crisis-Specific Themes (Table 1)

Situational awareness was a key executive function, through gathering and interpreting pertinent crisis information. Leaders grappled with decision-making in the face of uncertainty and rapid adaptation to changing clinical and educational protocols.

Increasing multidimensional communication beyond existing networks was essential. A web page was published with current information and links. Frequent email and Zoom check-ins kept everyone updated. A “Chief’s COVID-19 Roundtable” facilitated joint problem-solving. Improving communication with isolated community family physicians was highlighted.

The executive demonstrated emotional awareness of the pandemic’s impact, with opportunities to vocalize fears and address concerns. Staying calm and reassuring staff and learners were priorities. Wellness and resilience initiatives were shared. There were expressions of positivity, optimism, and gratitude, despite challenges.

Innovations in education and patient care included rapid pivots to virtual care and education (Table 2). Alternative locations and protocols were launched for in-person care and COVID-19 assessments, mitigating the impact of the closure of some community FP offices.24 A province-wide webinar program was launched to provide resources and support for FPs.

Proactive planning for extended adaptation began shortly after the onset of the pandemic, such as anticipating the needs of incoming learners. Executive members expressed commitment to maintaining core functions.

|

Major Themes |

Exemplar Supporting Quotations |

|

1. Situational awareness |

“And our leaders have just pivoted on a daily basis, sometimes two or three times a day, to keep up with accreditors and medical schools and licensing bodies and the College [of Physicians].” (April 2020) “Some of the messages may change over time as the understanding changes over time as well. There has been a flood of information coming through. And that’s part of the risk, of course, that people will get snowed with information and then they miss some critical new issue coming up.” (March 2020) “I mean I think now we need to start thinking about living with COVID, not living afraid of COVID, right. We’re going to have to adapt.” (May 2020) [adaptability] |

|

2. Increasing multidirectional communication |

“... I want to congratulate the DFCM on some excellent communication. I really appreciate it. …I think that some common communication so we have some common understandings would continue to be helpful.” (March 2020) “... We are trying very hard to bring those family doctors together so that we can work for and advocate for all of them…I specifically mean the 250-odd [FPs] that we don't know [in our area] and that are not on our staff and that we've never communicated with before...the solo docs out there…They don't know what to do. They don't have access to our information or pipeline…Their isolation is palpable to me.” (March 2020) “Postgrad Medical Education is staying in really close contact with us. We're sending out the information as fast as we can. And of course, if site directors or residents have any issues, #7's* been amazing about getting back to people really quickly. If you have any questions, or if things pop up at your site, local questions or even for students in community placements, please let us know about it.” (March 2020) “We've also made a blog on our [web] page where people can submit stories, ideas, thoughts, reflections on what's going on at their sites.” (April 2020) |

|

3. Emotional awareness |

“And [name] mentioned physician and resident wellness. I think we'll turn to each other as much as we need to, and be sensitive to those around us and the anxieties of all of those around us. They will be looking to us for leadership” (March 2020) “And the overall message that we wanted to share … is one of gratitude and also perseverance. Because we believe that with careful thought, planning and design, our education leaders, our administrative staff and all of the people at your sites are actually moving mountains. They’re ensuring that our learners are having the best possible learning experiences in this year.” (May 2020) “I think we're all very deeply in this and we all have a lot of, you know, kind of an emotional response to it. And there’s a sense of a bit of fear and a lot of fear among those around us. And I'm sure we're all experiencing that, and doing our best to calm those fears. Including the fears of families and wondering why we're working in the first place, and shouldn't we just be at home? So I know I'm getting that. I’m feeling that. And I suspect that's happening across the board…You wake up in the morning and you realize it's actually happening, and you can't quite believe it.” (March 2020) “The first is there have been numerous wellness and resilience initiatives at all of the sites. We'll be collating or synthesizing some of the awesome work that people are doing across sites to really streamline this.” (April 2020) |

|

4. Innovations in education and patient care |

“So as many of you know, we've had a very strong reflection on the digital nature of education and family medicine, and had been working at this for about three years… it is going to be a department-wide initiative that will look at education as a piece of that, but also research, global health and quality improvement. So, #20, we are building the infrastructures, and recognize how important, how incredibly important… COVID is just the precipitant to make us bring this out sooner.” (April 2020) “All the seminars that we used to do in person have now been converted into Zoom seminars, and they're all live. So one of the things that distinguishes us from some of the other courses that are running in the [name of faculty] is they have, for example, video seminars, and we don't have those. They're all live.” (May 2020) |

|

5. Proactive planning for extended adaptation to pandemic |

“We can't stay in our bunkers forever and not do anything. And I think we need these positive programs [leadership program] to move people forward and to give people hope that there's a light at the end of the tunnel. Because we can't just sort of do the bare minimum forever. And whether we need to figure out the new normal, this is one way to do it.” (May 2021) “And for sure, we're going to have a double cohort. …we will need to place two sets of clerks next year. And I will need all your help, all hands on deck, to get the students back [into clinical placements] so we can graduate a class on time.” (April 2020) “If we're going to be in this for another couple of years then virtual interaction is going to be a thing for people. And I actually think that for those leaders, participating in an interactive session, seeing how you run it, seeing how they can put their hand up and be recognized, those kinds of things are actually good leadership skills for people to pick up and to learn along the way.” (May 2020) |

* Numbers are substituted for participant names to prevent possible identification of individuals.

|

New Roles |

|

• Running hospital and mobile COVID assessment centres |

|

• Doing outreach to vulnerable patients within Family Health Teams |

|

• Developing neighbourhood hubs for alternate care (virtual, walk-in), if a patient’s family physician (FP) office closed |

|

• Supporting long term care and shelters, eg, swabbing, infection protection and control (IPAC), and personal protective equipment (PPE) education and supporting care |

|

• Providing support to community FPs (eg, procuring and distributing PPE) |

|

• Developing and sharing protocols for opening FM clinical practices safely (eg, new strategies to ensure social distancing, IPAC) |

|

• Advocating with the city government and agencies to create spaces where people can go to self-isolate if waiting for test results (eg, homeless) |

|

Adapted Roles |

|

• Supporting emergency department (ED), internal medicine, palliative, and addictions care in hospitals |

|

• Developing strategy for newborn assessment and pediatric immunization for patients whose FP office closed |

|

• Assisting with developing virtual collaborative team-based mental health care |

|

• Supporting wellness initiatives for FM staff and learners (eg, weekly virtual check-ins and forums) |

|

• Developing and conducting COVID-related research studies |

|

• Organizing rapid credentialing of community FPs to work in hospitals |

|

Innovations |

|

• COVIDCare@Home Program, a new clinical pathway to support patients with COVID-19 at home who do not have access to a family physician: • Patients received regular virtual check-ins with guidance to help manage their symptoms • Includes sending supplies to patients when needed (eg, O2 stat monitors, thermometers) |

|

• New low acuity emergency department facility as adjunct to emergency department was developed and run by family medicine (FM) |

|

• COVID-19 community of practice (CoP) in collaboration with Ontario College of Family Physicians (OCFP) so FPs across Ontario can connect and learn from each other: • Monthly, interactive webinars where practicing family physicians share their perspectives on COVID-related topics ranging from implementing virtual care, to organizing community collaboration, and supporting patient with mental health and addictions |

|

• Virtual educational seminars (Zoom) – live and interactive, examples: • Learners interview standardized patients followed by discussion in smaller break out groups in Zoom and with larger group • New education series “A Day in the Life of a Family Doctor During COVID” where learners can learn and ask questions about FM faculty experiences during COVID • Developing education program on how to teach physical exam skills virtually |

|

• Virtual Care Competency Training Roadmap (ViCCTR) program |

This research adds to the literature by systematically identifying the context, nature, and culture underpinning actions academic family physicians undertook in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The specific clinical and academic initiatives are similar to those previously reported. 1, 4-12

The six ongoing themes formed the foundation for the crisis response. The collegial environment fostered trust, considered essential for crisis management.40-45 Crises are unexpected, unstructured, characterized by incomplete and conflicting information, and outside typical operational frameworks.3, 25, 46 * The need for new approaches was evident in the emergence of five crisis-specific themes. Situational awareness is essential for developing strategies and making decisions during uncertainty.25, 28, 29 Along with increased multidirectional communication, this sustains trust in a chaotic and rapidly changing environment.

The ongoing themes of building capacity and expertise, striving for excellence, and developing leadership created an expectation to confront the crisis with authenticity, competence, and credibility.13, 25, 41, 44 Enhanced support for the well-being of the health care workforce, including trainees, is an important learning.16

The pandemic has highlighted the importance of quality primary care for population health47, 48 and the value of generalism for rapid adaptation to addressing emerging needs.49 This research suggests that the skills and culture of FM facilitate an effective crisis response.

A strength of analyzing meeting transcripts is avoiding recall bias by accessing discussions as they occurred, but a limitation is omission of nonverbal interactions. The six selected meetings underrepresent communications and discussions throughout the DFCM and focussed only on the initial onset of a pandemic that continues to generate crises and controversies. We assessed that our analysis achieved informational saturation, but we are cautious due to the limited data set.50 This study is exploratory; a richer grounded-theory approach capturing more executive meetings and discussions throughout DFCM’s 14 sites could provide greater insight into the response and its perceived effectiveness.

This exploratory study identifies six themes describing the cultural and organizational approaches that formed the foundation for the pandemic crisis response of academic FM leaders. Five crisis-specific themes reflect skills and attitudes that are essential in clinical family medicine, including adapting to community needs, communication, and emotional awareness.

* These descriptors usefully distinguish the COVID pandemic crisis from medical emergencies, for which there are recognized management protocols.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: This study was presented as an oral presentation entitled “Responding to COVID-19: A qualitative analysis of academic family physician leaders’ responses to an evolving crisis” at a virtual conference, November 20-23, 2021.

Conflict Disclosure: David White and Risa Freeman are members of the Executive of the Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto. Eva Grunfeld is a past member.

References

1. Kim CS, Lynch JB, Cohen S, et al. One academic health system’s early (and ongoing) experience responding to COVID-19: recommendations from the initial epicenter of the pandemic in the United States. Acad Med. 2020;95(8):1146-1148. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003410

2. Rosenthal U, Charles MT, Hart P. Coping with crises: the management of disasters, riots, and terrorism. Charles C Thomas Pub Limited; 1989.

3. Paixão G, Mills C, McKimm J, Hassanien MA, Al-Hayani AA. Leadership in a crisis: doing things differently, doing different things. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2020;81(11):1-9. doi:10.12968/hmed.2020.0611

4. Sorsby S, Schmit E, Ventres W. Workplace communication in the midst of COVID-19: making sense of uncertainty, preparing for the future. Fam Med. 2021;53(2):159-160. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.216908

5. Wu V, Shorr RI. Helping patients flourish in the midst of COVID-19. Fam Med. 2021;53(5):328-330. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.376920

6. Gold KJ, Laurie AR, Kinney DR, Harmes KM, Serlin DC. Video visits: family physician experiences with uptake during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fam Med. 2021;53(3):207-210. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.613099

7. Ledford CJW, Anderson LN. Communication strategies for family physicians practicing throughout emerging public health crises. Fam Med. 2020;52(5):48-50. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.960734

8. Krist AH, DeVoe JE, Cheng A, Ehrlich T, Jones SM. Redesigning primary care to address the COVID-19 pandemic in the midst of the pandemic. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(4):349-354. doi:10.1370/afm.2557

9. Glazier RH, Green ME, Wu FC, Frymire E, Kopp A, Kiran T. Shifts in office and virtual primary care during the early COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada. CMAJ. 2021;193(6):E200-E210. doi:10.1503/cmaj.202303

10. Everard KM, Schiel KZ. Changes in family medicine clerkship teaching due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Fam Med. 2021;53(4):282-284. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.583240

11. Pasala MS, Anabtawi NM, Farris RL, et al. Family medicine residency virtual adaptations for applicants during COVID-19. Fam Med. 2021;53(8):684-688. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.735717

12. Gigliotti RA. The impact of COVID-19 on academic department chairs: heightened complexity, accentuated liminality, and competing perceptions of reinvention. Innovative High Educ. 2021;46(4):429-444. doi:10.1007/s10755-021-09545-x

13. Ion R, Craswell A, Hughes L, et al. International nurse education leaders’ experiences of responding to the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(9):3797-3805. doi:10.1111/jan.14892

14. Rotenstein LS, Huckman RS, Cassel CK. Making doctors effective managers and leaders: a matter of health and well-being. Acad Med. 2021;96(5):652-654. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003887

15. Dirani KM, Abadi M, Alizadeh A, et al. Leadership competencies and the essential role of human resource development in times of crisis: a response to Covid-19 pandemic. Hum Resour Dev Int. 2020;23(4):380-394. doi:10.1080/13678868.2020.1780078

16. Aagaard EM, Earnest M. Educational leadership in the time of a pandemic: lessons from two institutions. FASEB Bioadv. 2020;3(3):182-188. doi:10.1096/fba.2020-00113

17. Dumulescu D, Muţiu AI. Academic leadership in the time of COVID-19-experiences and perspectives. Front Psychol. 2021;12:648344. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648344

18. Sklar DP. COVID-19: lessons from the disaster that can improve health professions education. Acad Med. 2020;95(11):1631-1633. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003547

19. Woolliscroft JO. Innovation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Acad Med. 2020;95(8):1140-1142. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003402

20. Laur CV, Agarwal P, Mukerji G, et al. Building health services in a rapidly changing landscape: lessons in adaptive leadership and pivots in a COVID-19 remote monitoring program. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(1):e25507. doi:10.2196/25507

21. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334-340. doi:10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G

22. Ellaway R, Bates J. Distributed medical education in Canada. Can Med Educ J. 2018;9(1):e1-e5. doi:10.36834/cmej.43348

24. Oandasan I, White D, Hammond Mobilio M, et al. Exploring and understanding academic leadership in family medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59(3):e162-e167.

25. Alknawy B. Leadership in times of crisis. BMJ Leader. 2019;3(1):1-5. doi:10.1136/leader-2018-000100

26. Koehn N. Leadership forged in crisis. Leader Leader. 2019;91(91):26-31. doi:10.1002/ltl.20407

27. Deitchman S. Enhancing crisis leadership in public health emergencies. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7(5):534-540. doi:10.1017/dmp.2013.81

28. Gigliotti RA. Crisis preparedness and the coronavirus pandemic: early reactions from University staff. Fresno State University; 2020. Accessed December 7, 2022. http://fresnostate.edu/adminserv/documents/Crisis%20Preparedness%20and%20the%20Coronavirus%20Pandemic_NCCI_Final.pdf

29. Kaul V, Shah VH, El-Serag H. Leadership during crisis: lessons and applications from the COVID-19 pandemic. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(3):809-812. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.076

30. Boin A, Kuipers S, Overdijk W. Leadership in times of crisis: a framework for assessment. Int Rev Public Adm. 2013;18(1):79-91. doi:10.1080/12294659.2013.10805241

31. Veenema TG, Deruggiero K, Losinski S, Barnett D. Hospital administration and nursing leadership in disasters: an exploratory study using concept mapping. Nurs Adm Q. 2017;41(2):151-163. doi:10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000224

32. White D. Preparing for COVID-19: the lessons from SARS 2003 in Canada. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2019;18(1). doi:10.22146/apfm.v18i1.216

33. Mahoney MC. Radiology leadership in a time of crisis: a chair’s perspective. Acad Radiol. 2020;27(9):1214-1216. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2020.05.042

34. Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine; 1967.

35. Boeije H. A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative data. Qual Quant. 2002;36(4):391-409. doi:10.1023/A:1020909529486

36. Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage. 2006.

37. Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ. 2000;320(7226):50-52. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50

38. Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483-488. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6

40. Reynolds B, Quinn Crouse S. Effective communication during an influenza pandemic: the value of using a crisis and emergency risk communication framework. Health Promot Pract. 2008;9(4)(suppl):13S-17S. doi:10.1177/1524839908325267

41. Reynolds B, Deitch S, Schieber RA. Crisis and emergency risk communication: pandemic influenza. CDC Stacks; 2007. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/7037

42. Hershkovich O, Gilad D, Zimlichman E, Kreiss Y. Effective medical leadership in times of emergency: a perspective. Disaster Mil Med. 2016;2(1):4. doi:10.1186/s40696-016-0013-8

43. Nathanial P, Van Der Heyden L. 2020. Framework and principles with applications to CoVid-19: INSEAD working Paper No. 2020/17/FIN/TOM. SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3560259 doi:10.2139/ssrn.3560259

44. Mcnulty EJ, Marcus LJ, Henderson JM. Every leader a crisis leader? Prepare to lead when it matters most. Leader Leader. 2019;2019(94):33-38. doi:10.1002/ltl.20470

45. Mainous AG III. A towering babel of risk information in the COVID-19 pandemic: trust and credibility in risk perception and positive public health behaviors. Fam Med. 2020;52(5):317-319. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.530121

46. Al-Dahash H, Thayaparan M, Kulatunga U. 2016. Understanding the terminologies: disaster, crisis and emergency. Proceedings of the 32nd Annual ARCOM Conference 1191–12000.

47. Robinson SK, Meisnere M, Phillips RL, Mccauley L; Board on Health Care Services. Committee on Implementing High-Quality Primary Care. 2021. Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press

48. Geyman JP. Beyond the COVID-19 pandemic: the urgent need to expand primary care and family medicine. Fam Med. 2021;53(1):48-53. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.709555

49. Seehusen DA, Ledford CJW. A clarion call to our family medicine colleagues. Fam Med. 2020;52(7):471-473. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.806737

50. Bowen G. Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept. Qual Res. 2008;8(1):137-152. doi:10.1177/1468794107085301

Lead Author

David G. White, MD, CCFP, FCFP

Affiliations: Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada | North York General Hospital, North York, ON, Canada

Co-Authors

Mary Ann O'Brien, PhD - Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Sylvie D. Cornacchi, MSc - Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Risa Freeman, MD, MEd, CCFP, FCFP - Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada | North York General Hospital, North York, ON, Canada

Eva Grunfeld, MD, DPhil, CCFP, FCFP - Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada | Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, Toronto, ON, Canada

Corresponding Author

David G. White, MD, CCFP, FCFP

Email: david.white@utoronto.ca

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.