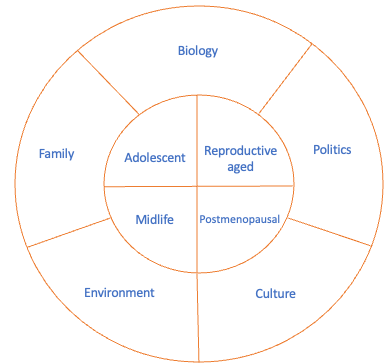

My senior resident scholarly project in 1995 was to develop a definition and model of women’s health. I used this basic model (Figure 1) to design a curriculum for a primary care women’s health fellowship. Since my fellowship, I have spent the past 28 years refining the model based on many hundreds of clinic and hospital visits of women at all life stages. My model consisted of two concentric circles. In the middle was a definition of the life cycle based on what was going on in a woman’s life. If she was pregnant, she was in the reproductive life cycle, whether she was 16 years old or 40, for example. The outer circle included biology, politics, environment, culture, and family. All these factors impact a woman’s life and health. To be an effective and impactful women’s health clinician, one must address each factor. It is straightforward to teach residents and students about biology, but more challenging convey how external factors contribute to a woman’s health.

FROM THE EDITOR

Teaching Women’s Health in Family Medicine

Sarina Schrager, MD, MS

Fam Med. 2024;56(4):217-218.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2024.798935

Family physicians are unique among women’s health providers. We see people at all life stages (from childhood, adolescence, reproductive years, midlife and older ages) and in many settings (hospital, clinic, home, nursing home, birthing centers). We are trained with an emphasis on wholistic care, seeing women within the context of their families, their unique cultures, and the world as a whole. Studies focusing on teaching women’s health in internal medicine residencies examine reproductive health 1, 2 and learning how to do breast and pelvic examinations. Family medicine clinicians are unique in that we address women’s health between internal medicine and obstetrics and gynecology. Our bread-and-butter curriculum covers basic obstetrics and gynecologic care.

Much has changed in women’s health over the last 3 decades, but much has remained the same. Definitions of gender have changed, with more conscious thought about the impact of biology as well as other inputs on gender. We no longer assume that the gender assigned to people at birth is their chosen gender later in life. Language has changed, with more deliberation about not alienating people based on their biologic gender at birth. Medicine has changed with now hundreds of different types of medications and imaging studies. Advances in infertility management and cancer management have greatly improved women’s lives.

Much has not changed, however. The impact of politics on women’s lives continues to come to the forefront in many of our patient encounters. Women dealing with poverty, violence at home, lack of access to safe living situations, insufficient food for their children, lack of access to reliable contraception, lack of health insurance, and in many states, no options for pregnancy termination if that is their choice. Our challenge as family medicine educators is to teach medical students and residents that women’s health is more than biology. It’s more than uteruses, ovaries, and breasts. It’s more than just the ways that diseases manifest differently in women than men. It’s more than how to insert an intrauterine device or etonogestrel implant. It’s women not being part of many foundational medical studies. It’s women oftentimes prioritizing their families over their own health. It’s the idea that where you live codifies your health care opportunities. Our challenge is to see women in the context of their daily lives.

For this issue, we are defining women’s health as the health of people born with ovaries, uteruses, and breasts, but acknowledge the overlap in concerns and conditions with people who are transgender or nonbinary.

This theme issue of Family Medicine, entitled “Teaching Women’s Health in Family Medicine,” includes studies examining the methods for optimal teaching of gynecologic procedures 3, 4 and articles looking at reproductive justice. 5, 6 This issue’s narratives poignantly share stories about labor 7 and access to abortion. 8 Ultimately, a theme issue represents the work that was submitted and revised based on peer review. It is remarkable how many of the papers submitted for this issue relate to reproductive health and access to abortion. In 1995, when I was doing my fellowship, a woman’s right to choose whether to continue a pregnancy was codified into law through Roe v Wade. In 2024, this is no longer the case. Women’s reproductive freedom is integrally related to our ability to provide wholistic, supportive, person-centered care. This is a key lesson offered in this theme issue and through the hundreds of women we care for weekly.

References

-

McClintock AH, Starks H, Williams M. Women’s health for a primary care workforce. Clin Teach. 2022;19(3):251-256. doi:10.1111/tct.13483

-

Henrich JB, Schwarz EB, McClintock AH, Rusiecki J, Casas RS, Kwolek DG. Position paper: SGIM sex- and gender-based women’s health core competencies. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(10):2407-2411. doi:10.1007/s11606-023-08170-y

-

Rezaiefar P, Waqas N, Archibald D, Humphrey-Murto S. Novel Performance Rating Instruments for Gynecological Procedures in Primary Care: A Pilot Study. Fam Med. 2024;56(4):234-241. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2023.261011.

-

Callen EF, Na'Allah R, Lewis A, Kerns J, Hester CM. Block Scheduling for LARC in a Family Medicine Residency Program. Fam Med. 2024;56(4):259-263. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2023.253918.

-

Kuizon C, Stumbar SE. Envisioning Reproductive Equity for All. Fam Med. 2024;56(4):264-265. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2024.211916.

-

Carvajal DN, McLean I, Wang L, Brahmi D, Washington JC. Equity and Justice in Family Medicine Clinical Care and Teaching Must Incorporate a Reproductive Justice Framework. Fam Med. 2024;56(4):222-228. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2024.973758.

-

Thomson C. A Magic Trick. Fam Med. 2024;56(4):266-266. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2024.140924.

-

Stumbar SE. Florida Abortion Clinic. Fam Med. 2024;56(4):267-267. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2024.706258

Lead Author

Sarina Schrager, MD, MS

Affiliations: Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI

Corresponding Author

Sarina Schrager, MD, MS

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.