Background and Objectives: Professional identity formation is a complex construct that continually evolves in relation to an individual’s experiences. The literature on educators identifying as faculty developers is limited and incompletely addresses how that identify affects other identities, careers, and influences on teaching. Twenty-six health professionals were trained to serve as faculty developers within our educational system. We sought to examine the factors that influence the professional identity of these faculty developers and to determine whether a common trajectory existed.

Methods: We employed a constructivist thematic analysis methodology using an inductive approach to understand the experiences of faculty developers. We conducted semistructured recorded interviews. Coding and thematic analysis were completed iteratively.

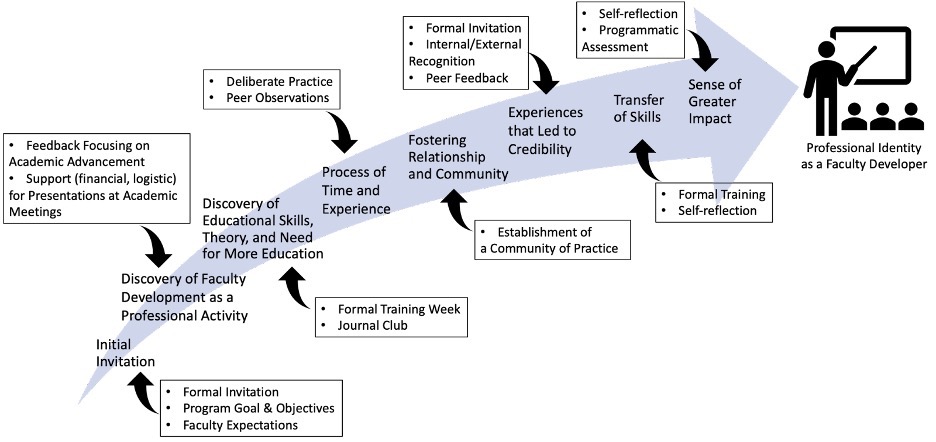

Results: We identified eight primary themes: (1) initial invitation, (2) discovery of faculty development as a professional activity, (3) discovery of educational theory, skills, and need for more education, (4) process of time and experience, (5) fostering relationships and community, (6) transfer of skills to professional and personal roles, (7) experiences that lead to credibility, and (8) sense of greater impact.

Conclusions: An individual’s journey to a faculty developer identity is variable, with several shared pivotal experiences that help foster the emergence of this identity. Consideration of specific programmatic elements to support the themes identified might allow for a strategic approach to faculty development efforts in health professions education.

Professional identity formation (PIF) is a critical process in health professions education. 1 Describing how individuals see themselves in a workplace setting, PIF can be understood as the complex, constant, and transformative process through which individuals take on their chosen profession’s perceived knowledge, skills, values, and behaviors. 2 Jarvis-Selinger et al described PIF as

an adaptive developmental process that happens simultaneously at two levels: (1) the level of the individual, involving the psychological development of the person and (2) the collective level involving the socialization of the person into appropriate roles and forms of participation in the community’s work. 3

Faculty developers—those individuals tasked with delivering faculty development activities—are charged with actively fostering the PIF of academic faculty through active experiences, promoting reflection, and relationship building. 4 To foster the PIF of faculty attending, faculty developers must be skilled in educational methods and facilitation, encouraging reflection across a diverse set of faculty and specialties. To better support these requisite skills, PIF in faculty developers demands explicit consideration. Moreover, considering the factors that influence one’s trajectory toward a professional identity as a faculty developer and the programmatic measures that support this trajectory provides a valuable roadmap for those departments or residency programs hoping to establish a cohort of faculty developers.

Several researchers have explored PIF in faculty developers. Faculty with content expertise periodically act as faculty developers and are frequently asked to deliver workshops to a larger group of faculty. These faculty developers experience PIF through numerous relationships with other identities, including parallel growth or merging. Impacts on the careers of periodic faculty developers include augmented intra- and interdepartmental credibility and relationships, increased national presentations, and academic promotion. 5 Faculty developers continue delivering faculty development because it enhances job satisfaction, connects the individual to the institution, refines mastery of teaching skills, and offers a sense of community with other like-minded individuals. 6, 7

Beginning in 2017, in response to accreditation requirements, our organization experienced an escalation in the number of faculty requesting and attending faculty development that surpassed our capability as faculty developers. To meet the demand for faculty development, we strategically trained a group of medical educators to serve as faculty developers, using a framework similar to the Stanford faculty development course. 8 We imagined that other large medical education organizations and their residencies, which use volunteer and community faculty, might be experiencing a similar increased need for faculty development. With these needs in mind, our research aimed to examine the factors that influence the professional identity of faculty developers. Specifically, our research question became: Is there a common trajectory for faculty developers as their identity as a faculty developer evolves? The answer to this question could inform our organization and others how to create an environment that fosters identity formation of faculty developers.

Setting and Participants

Our institution is a medical school within a large health system with 23 outlying teaching hospitals. Our formal training of core faculty developers began with the first group in 2017 and a second cohort in 2018. Participants completed an in-person weeklong instruction using a train-the-trainer model similar to the Stanford faculty development model. 8 Training focused on educational theory, content acquisition, and the development of facilitation skills. Subsequent practice, with feedback from an experienced faculty developer, took place as participants delivered workshops at a teaching hospital unfamiliar to them. The group provided faculty development at their local hospital and traveled to other teaching hospitals within our extended organization to assist with broader faculty development dissemination. The program is described in full elsewhere. 9 We invited all trained faculty developers to participate in this study: 26 individuals, including 2 dentists and 24 physicians, representing 12 different specialties.

Study Design

We conducted a qualitative study using semistructured interviews to collect data on the experiences of faculty developers. We chose thematic analysis as our analytic method toward understanding the experiences of our subjects. 10 We employed a constructivist paradigm grounded in theory to generate a new theoretical framework based on our codes and themes. However, we realized that our interpretations did not provide such a framework. Instead, we chose to focus our examination on the social and contextual factors of developing a professional identity as a faculty developer, ultimately building on existing concepts of professional identity in faculty developers. Approval for our study was obtained from the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (DBS.2020.129).

Interview Guide

We created our initial interview guide based on a published guide for interviewing faculty developers. 5 The research team, including the interviewer, met to adapt the guide through an iterative review process and discussion. A qualitative interview expert trained a single interviewer in two 1-hour sessions. The interviewer initially conducted six interviews, followed by a team discussion and a debrief of the interviewer’s experiences.

Data Collection

Via email, all faculty developers were invited to participate. One team member (CK) conducted the semistructured interviews from June to September 2020 over Google Meet. Seventeen of the 26 invited faculty developers participated. Verbal consent to participate and be recorded was obtained at the beginning of each interview. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and numbered. The interviewer masked participant names, specialties, and locations in the transcripts, leaving only the interviewer and the inviter aware of the identities of the interviewees; therefore, details of the participant sample cannot be included. The interviewer had no prior relationship with any participant and was not part of the participants’ faculty development training.

Coders initially familiarized themselves with the data by reading all the transcripts. The coders agreed on three transcripts with contrasting perspectives to create the original codebook. Each coder developed a list of codes and created a codebook through an iterative process of chunking and consensus-building. We used the codebook to code two transcripts. Only one of these two transcripts was required to standardize how the codes would be applied. The transcript used to standardize coding was not used in the data collection. We agreed to review and code the subsequent 12 transcripts. Each transcript was individually coded, and discussed by a dyad, six transcripts per dyad. Coded excerpts could be any length (from a phrase to a paragraph), and more than one code could be applied to each excerpt. During the meetings, dyads made field notes to reflect the discussion and highlight significant excerpts. One coder reviewed the remaining four transcripts, revealing no new codes. During the thematic analysis of the codes, coders and the interviewer met to create a thematic map.

Reflexivity

All study authors, except the interviewer, had a relationship with the participants. One (JS) oversaw all faculty development delivered by study participants, one (JH) developed the initial training, and three (JS, KM, and JH) trained all the study participants. Two (JB and GM) trained as faculty developers with the study participants, and one (TM) coordinated administrative contact with the participants. Team members included one senior medical student, one PhD scientist, and five physicians from different specialties, representing three outlying teaching hospitals and the medical school. All five physicians identified as faculty developers with 4 to 17 years of experience. Our own experiences with our faculty developer’s PIF evolution added to our participatory approach to the data analysis. 11

Thematic analysis yielded eight themes on a trajectory toward a professional identity as a faculty developer: (1) initial invitation, (2) discovery of faculty development as a professional activity, (3) discovery of educational theory, skills, and need for more education, (4) process of time and experience, (5) fostering relationships and community, (6) transfer of skills to professional and personal roles, (7) experiences that lead to credibility, and (8) sense of greater impact. When queried, nearly all interviewees had formed a professional identity as a faculty developer (n=15, 88%). The two faculty members who did not yet endorse a professional identity as faculty developers invoked elements of impostorism and a need for additional experience.

Our data, when taken as a whole, provided a common trajectory toward a professional identity as a faculty developer (Figure 1). Examination of this trajectory revealed common initiation steps followed by multiple related themes representing a relatively rapid rise toward a professional identity as a faculty developer. As this professional identity as a faculty developer was solidified, we noted themes supportive of the continued endorsement of this identity. Moreover, exploring these themes allowed for identifying programmatic elements that supported faculty on their trajectory to a professional identity as a faculty developer (Figure 2). Example comments supportive of identified themes are provided in Table 1.

|

Theme

|

Example

comment

|

|

Initial invitation

|

“With the FOCUS program in particular, I was nominated to participate in the initial FOCUS training group, and I thought it sounded like a great opportunity. So, I jumped right in and attended the weeklong training workshop.”

|

|

Discovery of faculty development as a professional activity

|

“I think it [faculty development] has opened my eyes into what’s required to be able to progress in education, whether it’s in the military or whether it’s in a civilian world.”

|

|

Discovery of educational theory, skills, and need for more education

|

“Well, I think as soon as I started getting into it, I realized that this was something that I was very interested in. It was always something that was simmering under the surface for me, but just not conscious of it. And maybe I just didn’t have the right words to put what I wanted to do, but as soon as I started to get exposed, everything just kind of just exploded in my head.”

|

|

Process of time and experience

|

“I think time and experience has definitely helped that evolve, and the deliberate practice of what we do throughout our FOCUS faculty sessions to learn specific skills related to teaching and facilitation.”

|

|

Fostering relationships and community

|

“I think it’s opened doors and provided opportunities that I wouldn’t have been necessarily a part of, but it’s also allowed me to really meet a broader scope of educators at my military treatment facility who I wouldn’t normally work with or interact with on a regular basis, but because of doing these faculty development seminars and lectures, I’ve really been able to meet a broad scope of educators, everyone from dentists to nurse practitioners in different departments to pharmacists.”

|

|

Transfer of skills to professional and personal roles

|

“And I guess I utilize a lot of the facilitation skills in my job when I’m on the IRB and I’m the vice-chair and sometimes chair the meetings. So, if I have to chair the IRB, I definitely utilize those facilitation skills that I’ve learned in faculty development in how I run the discussions at the IRB, which can often go off on tangents. So, having some facilitation skills helps out a lot with that.”

|

|

Experiences that lead to credibility

|

“Mainly because going through the training and having that training attached to my name and the fact that I can say I was selected and completed the faculty development training just gives me more credibility for the techniques and the things that I talk about and suggest. So, I do think it has helped solidify that identity in my department as well as in the hospital.”

|

|

Sense of greater impact

|

“It’s a real chance to make a difference across our organization to really be a force multiplier in education. You go from when you first start training that you want to help the patient, and then you want to have a larger sphere of influence, so you want to help trainees. And then from there, the next step is to really help those who are training the trainees and just increasing that ability to try and drive and make a system better.”

|

Initial Invitation

All interviewees identified the critical impact of being invited to train as a faculty developer. This invitation served as a vital impetus to begin one’s journey toward a professional identity as a faculty developer. The act of inviting is a big deal; this invitation carried a hidden message for both participants and others in the organization. Namely, there’s something special about this training and process. Indeed, several participants noted a preexisting personal interest in teaching and education, and therefore welcomed the invitation to expand on this interest through faculty development.

Discovery of Faculty Development as a Professional Activity

Once invited, interviewees frequently described a process of discovery—specifically, the discovery of faculty development as a distinct professional activity followed by the discovery of educational theory, skills, and the need for more education. Interviewees reported that the program’s opportunities, skills, and content knowledge supported advancement along an envisioned career trajectory while elucidating new academic career pathways. Many interviewees discussed having limited or no knowledge of faculty development as a career path prior to this experience. Additionally, interviewees noted that participating in the program clarified their overall understanding of the career possibilities within academic medicine.

Discovery of Educational Theory, Skills, and Need for More Education

Interviewees also reflected on how entry into faculty development opened their eyes to the possibility of additional growth opportunities and learning requirements. Interviewees alluded to their initial experiences attending faculty development as profound times of new exposure. Comments illuminated an awakening to educational theory, the need for medical educators to understand education, and an expanding perspective of all faculty development had to offer. Recognition of these possibilities fostered further self-directed learning within health professions education.

Process of Time and Experience

Following the discovery of faculty development as a career path and the requisite educational theories and skills required for successful faculty development, interviewees recognized that the process of becoming a faculty developer involves time and experience. This process also facilitated the transfer of learned skills to other professional and personal roles. While all interviewees described a process, each participant had a unique timeline with pivotal common experiences.

Fostering Relationships and Community

Many interviewees identified relationship building as a pivotal factor in developing an identity as a faculty developer. Essential relationships that developed in the process of becoming a faculty developer included having peer-to-peer interactions, building bridges with other faculty members at one’s institution and other teaching hospitals in our system, participating in national faculty development organizations, and establishing connections to executive and institutional leadership. Many interviewees spoke about their relationships with fellow physicians and other educators they otherwise would not have encountered. These interspecialty relationships helped establish their faculty developer identity because certain individuals saw them solely in that role.

Transfer of Skills to Professional and Personal Roles

Several interviewees commented on the applicability of faculty development skills to other professional and personal roles. These skills included communication, group facilitation, and administration. The comments revealed a clear trend: Faculty development skills transferred to being a more effective leader. Additionally, interviewees commented on applying these skills to personal roles, including parental and familial duties.

Experiences That Lead to Credibility

Participants depicted both the evolution of internal credibility and validation from external sources. Several interviewees’ internal credibility grew from a deeper understanding of the material and use of language associated with education. The selection to be part of the program was a type of external validation. Additional external validation came from coaching and feedback, words of appreciation, awards, honors, and further speaking invitations from educational leaders.

Sense of Greater Impact

Interviewees described contributing to something bigger than themselves or advancing a culture shift. Interviewees commented on how they evolved from having an individual focus to an organizational one. They recognized a broader impact than just the individuals they were teaching. This sustaining factor became particularly evident to interviewees as they became more established in their professional identity as a faculty developer.

Our study identified a common trajectory toward a professional identity as a faculty developer among interviewees. We identified eight primary themes along this trajectory. Examining our faculty development program through the lens of these eight themes allowed us to identify vital programmatic elements that supported our faculty on their trajectory toward a professional identity as a faculty developer.

A recent examination of PIF in faculty developers similarly explored constructing a professional identity as a faculty developer. 6 In contrast to the trajectory we described here, that group reported on a convergence of factors in this process; that is, faculty bring diverse life experiences, professional pathways, and backgrounds to a shared work environment. Rather than a convergence of factors, our study clarifies a trajectory toward an identity as a faculty developer and the interventions that institutions, leaders, or individuals might make to grow and maintain faculty developers to meet the increasing demand in health professions education. Exploration of these themes reveals practices within our program that support faculty on their trajectory to a professional identity as a faculty developer. Furthermore, examining the programmatic measures that support faculty developers on their trajectory provides a valuable exercise for clinical departments and residency programs interested in establishing a faculty development program.

Programmatically, to open the door for educators into faculty development, the first step is to create a community where an individual might be invited. Acceptance of this invitation provides room for discovering critical educational theory and skills. Supportive programmatic measures implemented in the initial invitation include valuing the perspectives of invited faculty, reviewing the program’s goals and objectives, and setting expectations for invited faculty members. 12

Participants in this study also described eye-opening experiences: the need for more education and the potential of faculty development as a career path. The discovery of faculty development as a career path is unique to this study. Medical trainees are aware of graduate medical education (GME) leadership positions when they begin training but may be unaware that teaching other faculty is a career option. The presence of a clear career path for educators has been reported as a facilitator for PIF among GME faculty. 13, 14 Programmatic measures we identified to support the discovery of faculty development as a professional activity include providing participants feedback focused on academic advancement and giving financial and logistic support for participants to present at academic meetings.

Participants expressed a realization of a whole new body of knowledge and practice they did not previously know existed and a continued need to heighten this knowledge. The focus on educational theory and skill development during the initial week of training likely contributed to the eye-opening experience described by the interviewees. Moreover, including a journal club in bimonthly program meetings maintained this focus. Interviewees applied these new insights and skills to their faculty development role as well as to their primary educational role.

To ensure that the process of time and experience is supported, educators must be mentored and sponsored to provide them with ongoing opportunities to practice the leadership and facilitation skills faculty development requires. Indeed, prior work identified similar factors that facilitate PIF among GME educators, including an invitation to participate, inclusion within a community supportive of teaching, support of mentors, and involvement in legitimate educational activities. 2, 5, 15-20 Repeated practice reinforces belonging in the faculty development community and allows individuals to grow their abilities and identity. This concept is consistent with Lave and Wenger’s description of situated learning. New entrants into a community of practice begin their involvement through legitimate peripheral participation in the community’s activities. 21 As individuals grow in content knowledge and knowledge of the community, participants move from peripheral to full participation.

With dwindling state and federal funding for education efforts and increasing pressure on the clinical revenue cycle, faculty development efforts are scrutinized because they do not generate revenue. One argument supporting the value of faculty development efforts is that skills transfer to other professional roles. Several participants in our study described this beneficial transfer of skills. The health professions education literature has raised concern that having several roles may create “role strain. 22, 23” Instead of creating an additional burden, our data suggest that expanding one’s role as a faculty developer may enhance performance in other roles of faculty developers (eg, clinicians, administrators, leaders, researchers). Programmatic elements to support skills transfer include formal training in facilitation and self-reflection.

Our study had several limitations. We completed the study at a single institution and within the context of a formal, centrally directed faculty development program. Potentially, our thematic analysis could show remarkable consistency because of this. A research team member not involved in the faculty development training conducted all interviews to minimize this potential effect. The resources invested in this program may limit the generalizability of our findings. Still, the consistency of responses across participants of diverse specialties and professions suggests a natural progression of PIF among faculty developers. A program such as ours may formalize and enhance the process. Future research on faculty development identity formation might elucidate how to develop more effective training programs for faculty developers. For example, research might explore tiering efforts to support faculty developers at different phases of their PIF and emphasizing specific skills that transfer to other professional roles.

In conclusion, we identified eight pertinent themes on a trajectory toward forming a professional identity as a faculty developer. These themes provide vital considerations for those tasked with meeting the ever-increasing demand for expanding faculty development in health professions education. Moreover, incorporating specific programmatic elements that support the themes identified in the trajectory we described will allow for a strategic approach to faculty development efforts in health professions education.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the views or official policy of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Department of the Army/Navy/Air Force, the Department of Defense, or US Government.

References

-

-

Wald HS. Professional identity (trans)formation in medical education: reflection, relationship, resilience.

Acad Med. 2015;90(6):701-706.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000731

-

Jarvis-Selinger S, MacNeil KA, Costello GRL, Lee K, Holmes CL. Understanding professional identity formation in early clerkship: a novel framework.

Acad Med. 2019;94(10):1,574-1,580.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002835

-

Steinert Y, O’Sullivan PS, Irby DM. Strengthening teachers’ professional identities through faculty development.

Acad Med. 2019;94(7):963-968.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002695

-

O’Sullivan PS, Irby DM. Identity formation of occasional faculty developers in medical education: a qualitative study.

Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1,467-1,473.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000374

-

Cavazos Montemayorr RN, Elizondo-Leal JA, Ramírez Flores YA, Cors Cepeda X, Lopez M. Understanding the dimensions of a strong-professional identity: a study of faculty developers in medical education.

Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1):1808369.

doi:10.1080/10872981.2020.1808369

-

O’Sullivan PS, Irby DM. What motivates occasional faculty developers to lead faculty development workshops? A qualitative study.

Acad Med. 2015;90(11):1,536-1,540.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000767

-

Johansson J, Skeff K, Stratos G. Clinical teaching improvement: the transportability of the Stanford faculty development program.

Med Teach. 2009;31(8):e377-e382.

doi:10.1080/01421590802638055

-

Servey J, Bunin J, McFate T, McMains KC, Rodriguez R, Hartzell J. The ripple effect: a train-the-trainer model to exponentially increase organizational faculty development.

MedEdPublish. 2020;9:158.

doi:10.15694/mep.2020.000158.1

-

-

Olmos-Vega FM, Stalmeijer RE, Varpio L, Kahlke R. A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE guide no. 149.

Med Teach. 2022;1-11.

doi:10.1080/0142159X.2022.2057287

-

Bunin JL, Servey JT. Meeting the needs of clinician-educators: an innovative faculty development community of practice.

Clin Teach. 2022;19(5):e13517.

doi:10.1111/tct.13517

-

Sethi A, Schofield S, McAleer S, Ajjawi R. The influence of postgraduate qualifications on educational identity formation of healthcare professionals.

Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2018;23(3):567-585.

doi:10.1007/s10459-018-9814-5

-

Irby DM, O’Sullivan PS. Developing and rewarding teachers as educators and scholars: remarkable progress and daunting challenges.

Med Educ. 2018;52(1):58-67.

doi:10.1111/medu.13379

-

de Carvalho-Filho MA, Tio RA, Steinert Y. Twelve tips for implementing a community of practice for faculty development.

Med Teach. 2020;42(2):143-149.

doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1552782

-

Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Supporting the development of a professional identity: general principles.

Med Teach. 2019;41(6):641-649.

doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1536260

-

Garth B, Kirby C, Nestel D, Brown J. ‘Your head can literally be spinning’: A qualitative study of general practice supervisors’ professional identity.

Aust J Gen Pract. 2019;48(5):315-320.

doi:10.31128/AJGP-11-18-4754

-

Jauregui J, O’Sullivan P, Kalishman S, Nishimura H, Robins L. Remooring: A qualitative focus group exploration of how educators maintain identity in a sea of competing demands.

Acad Med. 2019;94(1):122-128.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002394

-

Weber RA, Cable CT, Wehbe-Janek H. Learner perspectives of a surgical educators faculty development program regarding value and effectiveness: a qualitative study.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(3):1,057-1,061.

doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000475825.09531.68

-

Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education.

Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185-191.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826

-

-

Sethi A, Ajjawi R, McAleer S, Schofield S. Exploring the tensions of being and becoming a medical educator.

BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):62.

doi:10.1186/s12909-017-0894-3

-

Varpio L, Ray R, Dong T, Hutchinson J, Durning SJ. Expanding the conversation on burnout through conceptions of role strain and role conflict.

J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(6):620-623.

doi:10.4300/JGME-D-18-00117.1

There are no comments for this article.