Background and Objectives: Residency programs are expected to meet many requirements in training their residents, including providing adequate numbers of pediatric visits and procedures opportunities. In the residency program studied here, these numbers were inadequate, despite the efforts of faculty members over the years. A self-designated faculty champion (with traits including vision, persuasiveness, proactivity, and tenacity) launched a series of clinical initiatives to combat these problems.

Methods: The number of pediatric visits in the Family Medical Center (FMC) were tracked and compared from 2012, prior to the intervention led by the faculty champion, through 2023. The number of procedures performed in the FMC were tracked and compared from 2015, when the procedures-only clinic was launched by the faculty champion, through 2023.

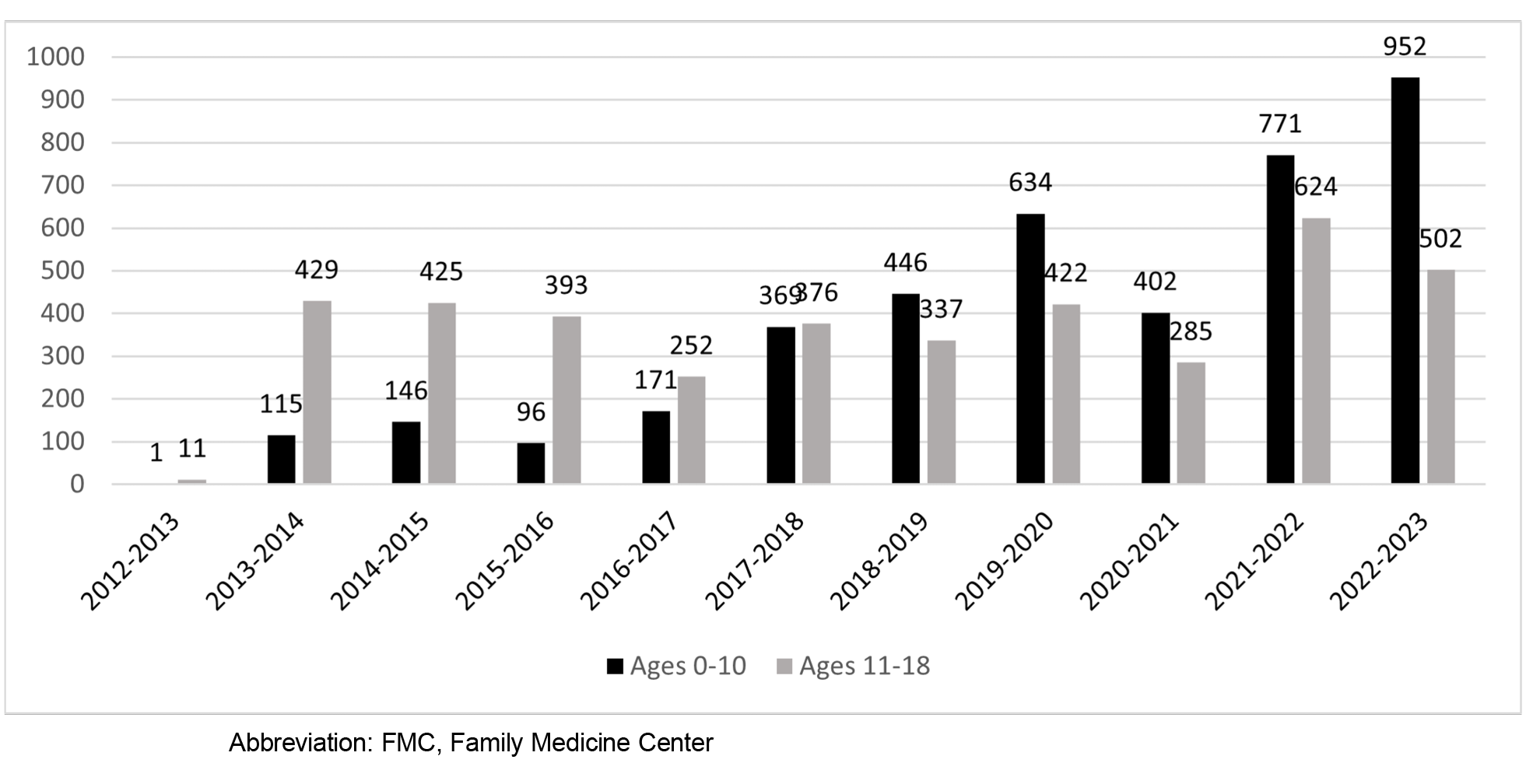

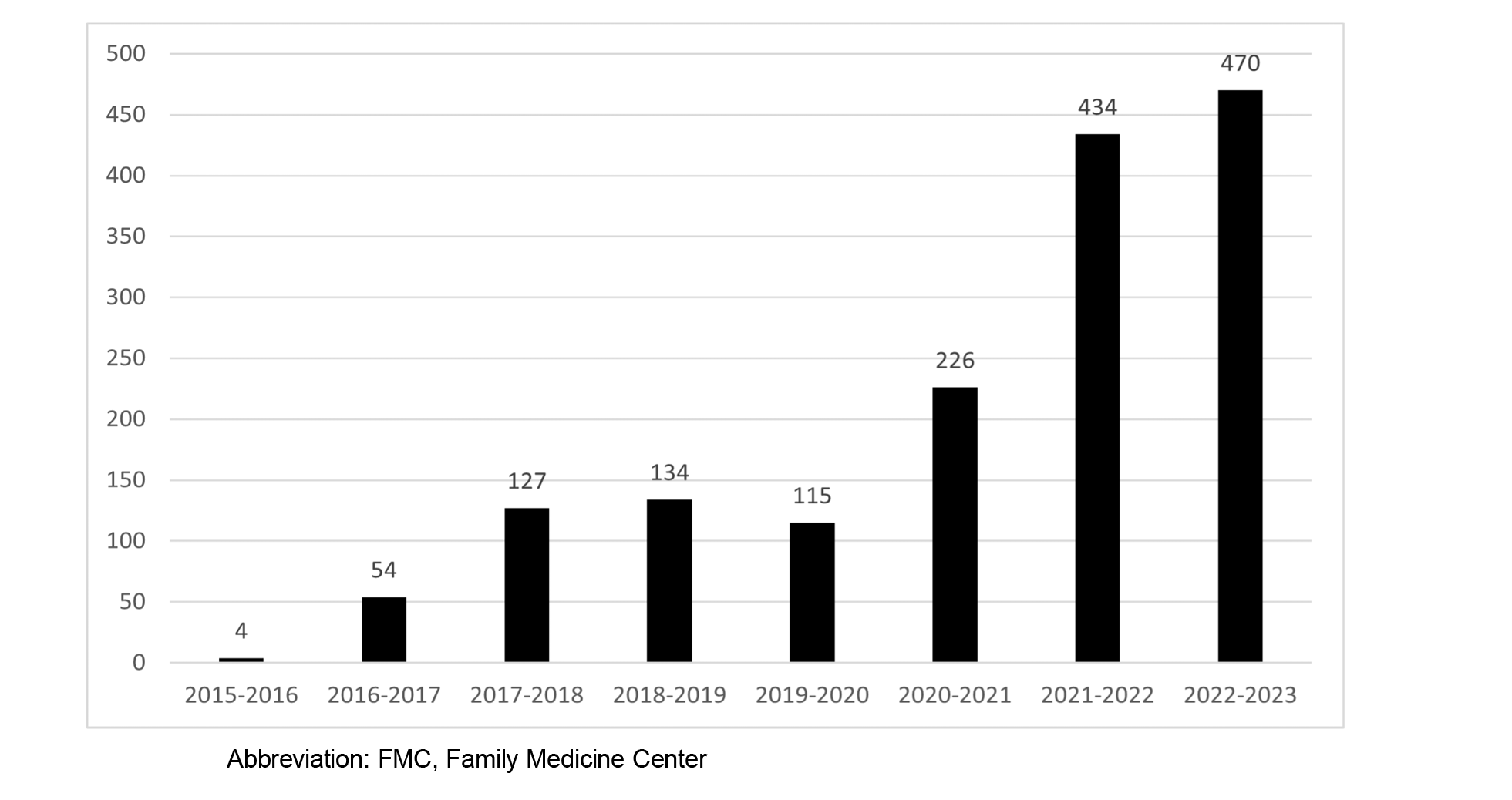

Results: The number of pediatric visits in the FMC in 2012–2013 was a total of 12. By 2022–2023, that number had grown to 1,454. The number of procedures in the FMC was four in 2015–2016, but by 2022–2023 had grown to 470. The improved numbers support competency-based medical education, with increased faculty observation, teaching, and evaluation. For procedures training, the improved numbers support faculty members in using the Procedural Competency Assessment Tools to evaluate resident performance.

Conclusions: A faculty champion who is interested, self-motivated, persistent, and focused on leading the project from beginning to end can bring about significant improvements in a residency program, despite the program’s track record of difficulty in making such improvements.

Finding the means to initiate improvements in a residency program can be daunting. Often the problem is not recognizing the need, but rather identifying strategies to execute improvements despite barriers 1 and finding a champion who possesses the skills to lead efforts in solving such problems.

The efficacy of a champion leading curricular improvements in family medicine residency programs has been established in several studies. This includes curricula in wellness and quality improvement, which have been championed by faculty and even residents. 2, 3 Programs with an oral health champion were more likely to provide training that resulted in residents being well prepared for board questions on oral health. 4 Having a faculty champion to lead a community medicine curriculum was found to be essential, 5 and the lack of a champion was identified as a top barrier to launching trauma-informed care training in family medicine. 6

Such champions, who are often found leading quality improvement strategies, tend to show enthusiasm, intrinsic motivation, and commitment to bring about change. They possess qualities including excellent communications skills, influence, grit, persuasiveness, ownership of change efforts, proactivity, empathy, ability to inspire and motivate, vision, perseverance, and the drive to bring about change. They often choose to become a champion, as opposed to being appointed, and they often flourish when they focus on areas of specific personal interest. 7 One study divided change champions into two categories: those who champion a project, and those who lead organizational changes. In both situations, change champions were determined to be critical to success. 1, 8-14

The purpose of this study was to analyze the methods, processes, and outcomes of a faculty champion in increasing the numbers of pediatric visits and procedures performed in a family medicine residency program. These two areas were the focus because the program had a history of struggling to meet Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requirements in both cases.

IRB Statement

The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) Institutional Review Board determined that this project is not human subject research and does not fall under the jurisdiction of the IRB review process (IRB# 274344).

Pediatrics

Prior to 2012, the number of pediatric visits in the Family Medical Center (FMC) on the UAMS Little Rock campus was very small. In 2012, a self-identified faculty champion in the residency program emerged, analyzed the problem to pinpoint five areas most in need of change, and led all aspects of the transformation.

-

Fostering buy-in from faculty, residents, and staff. This was a complex process that involved persuasiveness, explanation that ACGME requirements must be met, and assurance that training, equipment, and supplies would be provided.

-

Facilitating readiness through training and equipment purchases. Didactics and workshops taught by pediatricians were scheduled. Staff members went to the UAMS Newborn Nursery and to Arkansas Children’s Hospital for training, especially on infants. Supplies (eg, play equipment, medical supplies, an infant scale, a measuring board, stickers, toys, books, and pediatrics lab supplies) were purchased, and vaccines were made available. The faculty champion relied on strong communication skills and the ability to motivate staff members to be willing to learn and take on new tasks.

-

Building a schedule to support dedicated pediatric slots. At first, resident scheduling templates were redesigned to allow for dedicated pediatrics slots during which no adults could be scheduled. The faculty champion negotiated this process and later facilitated the addition of a pediatrics resource template, allowing for the scheduling of pediatrics patients with no limit on the number of slots.

-

Recruiting pediatric patients from Arkansas Children’s Hospital and the UAMS Newborn Nursery. This effort included tenacious negotiating with their leadership, marketing the FMC services, and making the waiting area and clinic rooms more welcoming to children and families.

-

Budget. The necessary funds were provided by the residency program, the FMC, and the department in response to the champion’s vision, justifications, and advocacy.

Procedures

Prior to 2016, the opportunity for residents in the UAMS Little Rock family medicine residency program to perform procedures was limited. The faculty champion began by increasing his own procedural proficiency through workshops on ultrasound, joint injections, and other procedures. From there, the champion asked the faculty for referrals and requested a scheduling template and dedicated clinical space. At first, the procedures clinic was staffed by the faculty champion and one resident. That grew to two residents and students as well. Additional faculty members were trained and eventually became champions of the process. As the number of procedures increased, faculty members were able to incorporate the Procedural Competency Assessment Tools, 15 as recommended by the Council of Academic Family Medicine (CAFM) to evaluate resident performance in procedural skills.

The cost of some training was covered by faculty enhancement funds that already existed. The remainder was covered by the department chair on the premise that increased procedures would lead to additional clinical income.

Pediatrics

After years of stagnation, the numbers of pediatric patients in the FMC rose to levels that seemed impossible. Figure 1 shows the increase in pediatric visits since 2012.

Some growing pains were associated with the process. The faculty champion addressed issues and dealt with unforeseen difficulties, such as the COVID-19 pandemic that affected patient numbers across the board.

Procedures

When the procedures clinic launched in 2015–2016, the total number of procedure visits in the FMC was four. The number now is typically in the hundreds, as shown in Figure 2. The breadth of procedures also has grown and now includes approximately 10 dermatological procedures, 15 musculoskeletal procedures, and 10 women’s health procedures.

After years of futile efforts, one interested, enthusiastic, and self-identified faculty champion 8, 9 with proper support and resources was able to build the framework to improve the numbers of pediatric visits and procedures. The improved numbers, while not necessarily a stand-alone indication of curriculum improvement, support competency-based medical education as required by ACGME 16 with the enhanced resident experience resulting in more faculty observation, teaching, and evaluation. For procedures training, the improved numbers support faculty members in using the Procedural Competency Assessment Tools 15 as recommended by CAFM to evaluate resident performance in procedural skills. Prior to the significant increases in pediatrics and procedures numbers, such robust evaluation and curriculum development would have been almost impossible.

Budgetary needs were small for this project, given that the improvements were implemented over a period of years and that some training was covered by faculty enhancement funds. Other program curricula were improved when faculty members and residents began championing their own interests in diverse areas, including research, wellness, lifestyle medicine, opioid stewardship, and community outreach. Champion characteristics such as taking ownership, persisting, and maintaining self-motivation have been keys to success. 8-14

Limitations of this study included the small size of the residency program and the generalizability of results, because faculty motivation and barriers can vary from program to program. Though this study focused on pediatrics and procedures, the usefulness of a champion can be applied to any curricular or other program challenges.

Next steps include analyzing the identification of champions and determining whether appointed champions function as well as those who volunteer. Another consideration is determining what faculty development strategies might encourage faculty members to become champions and whether similar strategies are workable for residents and other staff members.

A self-motivated, energetic, and proactive champion with drive and tenacity can conquer problems that have stymied less persistent leaders in residency training. One champion also can inspire others to step forward as champions to lead improvements where needed.

Presentations

An earlier version of the topic was presented as a poster at the American Academy of Family Physicians Family Medicine Experience Conference in October 2021 (virtual conference).

References

-

Demes JAE, Nickerson N, Farand L, et al. What are the characteristics of the champion that influence the implementation of quality improvement programs?

Eval Program Plann. 2020;80:101795.

doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2020.101795

-

Penwell-Waines L, Runyan C, Kolobova I, et al. Making sense of family medicine resident wellness curricula: a Delphi study of content experts.

Fam Med. 2019;51(8):670-676.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.899425

-

Grover P, Volshteyn O, Carr DB. Physical medicine and rehabilitation residency quality improvement and research curriculum: design and implementation.

Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;100(2,Suppl 1):S23-S29.

doi:10.1097/PHM.0000000000001550.

-

Silk H, Savageau JA, Sullivan K, Sawosik G, Wang M. An update of oral health curricula in US family medicine residency programs.

Fam Med. 2018;50(6):437-443.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.372427

-

Vickery KD, Rindfleisch K, Benson J, Furlong J, Martinez-Bianchi V, Richardson CR. Preparing the next generation of family physicians to improve population health: a CERA study. Fam Med. 2015;47(10):782-788.

-

Dichter ME, Teitelman A, Klusaritz H, Maurer DM, Cronholm PF, Doubeni CA. Trauma-informed care training in family medicine residency programs: results from a CERA survey.

Fam Med. 2018;50(8):617-622.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.505481

-

-

Damschroder LJ, Banaszak-Holl J, Kowalski CP, Forman J, Saint S, Krein SL. The role of the champion in infection prevention: results from a multisite qualitative study.

Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(6):434-440.

doi:10.1136/qshc.2009.034199

-

Miech EJ, Rattray NA, Flanagan ME, Damschroder L, Schmid AA, Damush TM. Inside help: an integrative review of champions in healthcare-related implementation.

SAGE Open Med. 2018;6.

doi:10.1177/2050312118773261

-

Soo S, Berta W, Baker GR. Role of champions in the implementation of patient safety practice change.

Healthc Q. 2009;12(Sp):123-128.

doi:10.12927/hcq.2009.20979

-

Stevens B, Bueno M, Rao M, et al. An exploratory case study investigating the implementation of a novel knowledge translation strategy in a pandemic: the Pandemic Practice Champion.

Implement Sci Commun. 2022;3(1):45.

doi:10.1186/s43058-022-00294-2

-

Bonawitz K, Wetmore M, Heisler M, et al. Champions in context: which attributes matter for change efforts in healthcare?

Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):62.

doi:10.1186/s13012-020-01024-9

-

Flanagan ME, Plue L, Miller KK, et al. A qualitative study of clinical champions in context: clinical champions across three levels of acute care.

SAGE Open Med. 2018;6.

doi:10.1177/2050312118792426

-

Shaw EK, Howard J, West DR, et al. The role of the champion in primary care change efforts: from the State Networks of Colorado Ambulatory Practices and Partners (SNOCAP).

J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(5):676-685.

doi:10.3122/jabfm.2012.05.110281

-

-

Newton WP, Magill M, Barr W, Hoekzema G, Karuppiah S, Stutzman K. Implementing competency based ABFM board eligibility.

J Am Board Fam Med. 2023;36(4):703-707.

doi:10.3122/jabfm.2023.230201R0

There are no comments for this article.