Background and Objectives: Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is an important concept for family medicine and is part of several Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education milestones. Social media (SM) has become a cornerstone in most of our lives. Previous studies show the use of SM in medical education is expanding. The objective of this study is to use SM for medical education focusing on teaching EBM through an innovative, engaging video series.

Methods: This quasi-experimental study used pre- and postintervention surveys between May 2022 and June 2022 using the American Board of Family Medicine National Journal Club initiative as a foundation. A total of 196 residents and fellows from various family medicine residency programs were eligible to participate. Surveys consisted of SM usage, EBM engagement, EBM comfort and confidence adapted from a validated tool, and questions about the articles reviewed in the videos.

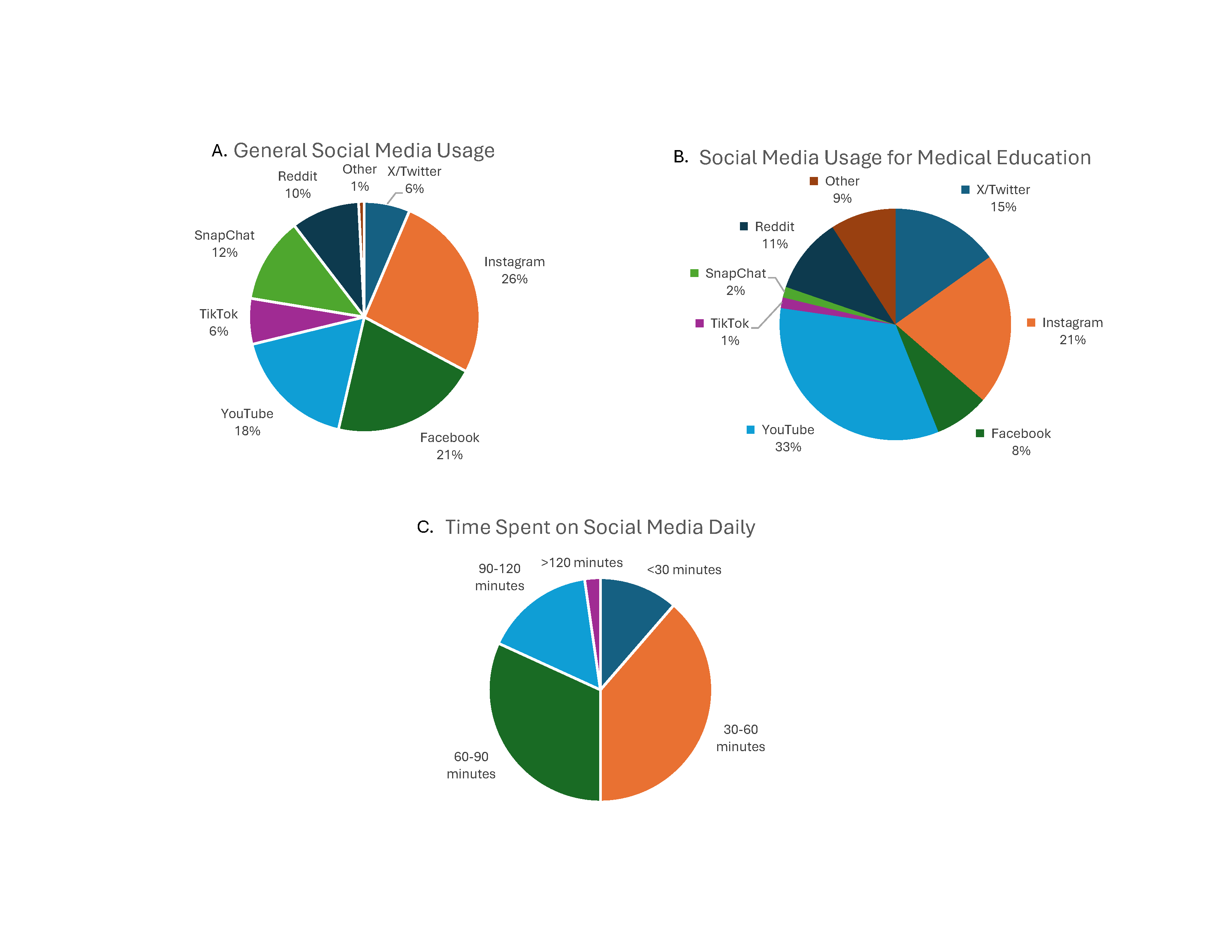

Results: A total of 44 of 196 residents and fellows from various family medicine residency programs participated in the preintervention survey. Most participants identified learning about EBM through residency didactics. The most popular SM platforms were Instagram and YouTube for medical content. Participants were least comfortable on the 10-point scale for critically appraising study methods. Postintervention cumulative scores for knowledge about the journal articles increased from 64% to 85%.

Conclusions: The video series taught EBM concepts and were well received, albeit with a low postintervention response rate. These findings contribute to the evolving landscape of medical education with implications for improving the effectiveness of EBM teaching through SM platforms.

Teaching evidence-based medicine (EBM) has been studied in medical education and is a key component in the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) milestones. 1-6 However, program directors have reported issues protecting resident time for teaching EBM, having faculty unprepared to deliver feedback on EBM skills, and being skeptical overall about EBM. 7 When EBM is delivered in a structured, longitudinal way, learners have significant increases in comfort and confidence using EBM through a validated assessment tool. 8, 9

Social media (SM) is a technology-based platform where users create and interact with content on a global scale.10 SM use in medical education is growing with an exponential rise in publications since 1996.10-12 A recent review found X (formally Twitter) was used in 157 publications, Facebook in 103, and blogs and podcasts in 176. 11 Learners use SM for professional networking, acquisition of procedural skills, and recruitment. 12-16 Studies have shown that SM is an effective adjunct to didactic content, improving learner engagement and amplifying publication views. 17-22 Our purpose was to create a novel method of EBM teaching that uses SM to disseminate content and to evaluate its effectiveness.

We aimed to describe learners’ (a) current SM use; (b) current engagement, confidence, and comfort with EBM principles and resources; and (c) change in knowledge of EBM concepts and emerging clinical information. UPMC has eight family medicine residency programs, with a total of 196 learners in the 2021-2022 academic year.

Procedures

This project was supported by the American Board of Family Medicine through a $5,000 grant to promote its National Journal Club initiative where recipients were asked to innovate EBM teaching. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh approved this study.

In April 2022, the cohort of 196 learners was emailed study information and asked to complete an anonymous preintervention survey. Starting in May 2022, our video intervention was posted weekly for 6 weeks to our program’s SM, which included YouTube, Instagram, Facebook, and X (formerly known as Twitter). Additionally, the cohort was emailed the same links weekly for rolling recruitment. Because anyone could access our SM, emails ensured that only members of the cohort responded to the surveys. The final video was shared in June along with the postintervention survey. Participants received a $5 gift card for completing each survey; those completing both were entered into a raffle for $100 gift cards at study completion.

Each video was divided into two parts: case scenarios and EBM teaching. During the case portion, learners followed an investigation of clinical questions using the latest evidence. Each incident is investigated using storytelling to illustrate trial outcomes. During the EBM teaching portion, the video used an article as a basis to review concepts. Table 1 provides an overview of the articles reviewed, concepts taught, and overall viewership.

|

Video

|

Article

|

Clinical EBM

teaching points

|

Statistical EBM

teaching points

|

Viewership

(total)*

|

|

1

|

Charging Murder Is No Yolk!

|

Association Between Egg Consumption and Risk of Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by Krittanawong et al 23

|

Eating more than one egg a day is not associated with an increased risk of ASCVD.

|

• POEMs vs DOEs

• Levels of evidence

• Hazard ratios

|

311

|

|

2

|

Saying DOACs Are Better, Just A-Fib?

|

Rivaroxaban in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation and a Bioprosthetic Mitral Valve by Guimaraes HP et al 24

|

Rivaroxaban was noninferior to warfarin with respect to time until death, major cardiovascular disease, and major bleeding in patients with bioprosthetic mitral valves and A-Fib.

|

• PICOs

• Noninferiority

|

200

|

|

3

|

COPD, A Place Where Beta-Blockers Be-Lung?

|

Association of β-Blocker Use With Survival and Pulmonary Function in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary and Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by Yan-Li Yang et al 25

|

Patients with COPD who take beta-blockers had a reduction in all-cause and inpatient mortality, and those who took cardio-selective agents had a reduction in COPD exacerbations.

|

• Forest plots

• Confidence intervals

• Trial weights

|

361

|

|

4

|

Exercise, Numero Uno in Concussion Treatment?

|

Early Subthreshold Aerobic Exercise for Sport-Related Concussion by Leddy et al 26

|

Subsymptom threshold aerobic exercise prescribed to adolescents with concussion symptoms is safe, speeds recovery, and may reduce incidence of chronic concussions.

|

• Masking and blinding

• Allocation concealment

• Simple vs block vs stratified randomization

|

315

|

|

5

|

The Man Behind the Curtain

|

Association of Low-Value Testing With Subsequent Health Care Use and Clinical Outcomes Among Low-Risk Primary Care Outpatients Undergoing an Annual Health Examination by Bouck et al[27]

|

Testing in low-risk patients as part of an annual health exam increases the likelihood of subsequent specialist visits, diagnostic tests, and procedures.

|

• Propensity-matched scoring

|

390

|

|

6

|

It’s Not a SPRINT, It's a Marathon

|

Blood Pressure Targets in Adults With Hypertension (Review) by Arguedas JA et al 27

|

Lower blood pressure targets may reduce MI and CHF but may increase other serious adverse events with no difference in death from any cause or total serious adverse events.

|

• Forest Plots

• Relative Risk

• Confidence Intervals

• Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool

|

427

|

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

This quasi-experimental study used a pre- and postintervention survey. Surveys were reviewed by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh. Respondent data from the two surveys were linked with a unique identifier using Qualtrics (Qualtrics LLC). The preintervention survey included (a) demographics; (b) SM usage in general and for medical education; (c) EBM engagement; (d) EBM comfort/confidence; and (e) questions pertaining to each video (a clinical concept and an EBM concept). EBM comfort/confidence was identified via an adapted validated scale. 8 The postintervention survey consisted of (a) the same questions related to the videos for recall; (b) an assessment of the intervention; and (c) overall engagement.

Forty-four of a possible 196 learners (22.4%) participated in the preintervention survey. Respondents included 13 postgraduate year 1 family medicine residents, 11 postgraduate year 2 family medicine residents, 10 postgraduate year 3 family medicine residents, 3 fellows, and 7 pharmacy residents. Respondents identified residency didactics as the main resource to review primary medical literature (86%) followed by journal websites (61%), applications (52%), podcasts (34%), and SM (23%). For EBM engagement, 89% of respondents reported spending at least 30 minutes daily using secondary resources to review literature for learning purposes. Most respondents (55%) strongly agreed that EBM was part of their residency’s culture, and 80% identified EBM as important. EBM confidence/comfort is reported in Table 2. Respondents were least comfortable with critically appraising study methods. SM respondent use is reported in Figure 1. Of note, 52% used SM and podcasts 15 or fewer minutes per week for EBM.

|

Question

|

Minimum

|

Maximum

|

Mean

|

Standard

deviation

|

Variance

|

|

1

|

How confident are you in your ability to identify a gap in your knowledge related to a patient or client situation (eg, history, assessment, treatment)?

|

3

|

10

|

7.61

|

1.65

|

2.74

|

|

2

|

How confident are you in your ability to formulate a question to guide a literature search based on a gap in your knowledge?

|

4

|

10

|

7.18

|

1.6

|

2.56

|

|

3

|

How confident are you in your ability to effectively conduct an online literature search to address the question?

|

3

|

10

|

7

|

1.68

|

2.82

|

|

4

|

How confident are you in your ability to critically appraise the strengths and weaknesses of study methods (eg, appropriateness of study design, recruitment, and data collection and analysis)?

|

3

|

10

|

5.77

|

1.64

|

2.68

|

|

5

|

How confident are you in your ability to determine whether evidence from the research literature applies to your patient’s situation?

|

4

|

10

|

6.89

|

1.37

|

1.87

|

|

6

|

How confident are you in your ability to ask your patient about his/her needs, values, and treatment preferences?

|

4

|

10

|

8.23

|

1.44

|

2.08

|

|

7

|

How confident are you in your ability to decide on an appropriate course of action based on integrating the research evidence, clinical judgment, and patient preferences?

|

3

|

10

|

7.18

|

1.37

|

1.88

|

|

8

|

How confident are you in your ability to continually evaluate the effect of your course of action on your patients’ outcomes?

|

2

|

10

|

6.84

|

1.74

|

3.04

|

Overall, respondents scored 64% cumulatively on the preintervention survey of the EBM questions that were subsequently covered in the video series. Question results with the lowest scores were about the effects of egg consumption on cardiovascular disease (11%), the effects of lower blood pressure on mortality (36%), and the purpose of propensity scoring (43%).

Videos averaged 334 views (200 to 427 views). Following the videos, seven respondents completed the postintervention survey. Respondents used YouTube and Instagram for video access. Overall, respondents scored 85% cumulatively on the postintervention survey of the video-related questions. Only one respondent’s score decreased from the preintervention survey and four participants’ scores improved. All respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the series enhanced their EBM knowledge and that they would share a similar video series with coworkers/learners.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies on engaging learners in family medicine residency programs using SM to disseminate EBM teaching. Respondents noted that their primary source of emerging literature comes from didactics. Given that ACGME milestones include EBM concepts, we feel that learners should practice finding and evaluating the best available evidence. Our project encouraged SM use for EBM content and taught concepts through educational videos. Importantly, postintervention results showed improvement, which is encouraging, for the use of SM to teach.

Respondents to the preintervention survey preferred to engage with medical education on SM built around videos (YouTube and Instagram). This may represent a shift from older platforms like X and Facebook where videos are less common and shorter.28, 29 Given this finding, we hypothesize that content for learners may best be created in video format. Average video views (334) exceeded the total number in the cohort (196), meaning that videos either were watched multiple times or reached beyond our cohort (Table 1). Anecdotally, applicants to our residency program mention the video series in interviews. SM can be accessed asynchronously and without intent to learn. Educators may want use SM to capitalize on these attributes.

Respondents’ lowest self-assessment in the EBM comfort/confidence scale focused on their ability to apply EBM to articles (Table 2). These included the ability to critically appraise evidence, evaluate treatment effectiveness, and determine the relevance to patients. Our videos attempted to influence these areas by equally distributing allotted time to education and critical appraisal. Learners felt most confident identifying their own knowledge gaps.

Limitations include low postintervention response rate and not evaluating changes in EBM comfort/confidence in this survey. To remove the burden of completing the scale a second time, we decided not to collect these data because the survey was distributed in the final week of an academic year, where residents’ attention to it may have been diminished. These data may have provided insight on EBM comfort/confidence following the series. Nonetheless, postintervention scores on the video-related questions increased, perhaps showing that confidence/comfort in critical appraisal increased.

The results of this project describe EBM comfort and use of SM in medical education. Further studies are needed to understand the relationship SM may have with learner retention and engagement.

References

-

Mai DH, Taylor-Fishwick JS, Sherred-Smith W, et al. Peer-developed modules on basic biostatistics and evidence-based medicine principles for undergraduate medical education.

MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:11026.

doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11026

-

Anderson CR, Haydek J, Golub L, et al. Practical evidence-based medicine at the student-to-physician transition: effectiveness of an undergraduate medical education capstone course.

Med Sci Educ. 2020;30(2):885-890.

doi:10.1007/s40670-020-00970-9

-

Song C, Porcello L, Hernandez T, Levandowski BA. Description and evaluation of an evidence-based residency curriculum using the evidence-based medicine environment survey.

Fam Med. 2022;54(4):298-303.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2022.652106

-

Rahimi-Ardabili H, Spooner C, Harris MF, et al. Online training in evidence-based medicine and research methods for GP registrars: a mixed-methods evaluation of engagement and impact.

BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):492.

doi:10.1186/s12909-021-02916-0

-

-

Paulsen J, Al Achkar M. Factors associated with practicing evidence-based medicine: a study of family medicine residents.

Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:287-293.

doi:10.2147/AMEP.S157792

-

Epling JW, Heidelbaugh JJ, Woolever D, et al. Examining an evidence-based medicine culture in residency education.

Fam Med. 2018;50(10):751-755.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.576501

-

Salbach NM, Jaglal SB. Creation and validation of the evidence-based practice confidence scale for health care professionals.

J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(4):794-800.

doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01478.x

-

Romney W, Salbach NM, Perry SB, Deutsch JE. Evidence-based practice confidence and behavior throughout the curriculum of four physical therapy education programs: a longitudinal study.

BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):839.

doi:10.1186/s12909-023-04821-0

-

Cheston CC, Flickinger TE, Chisolm MS. Social media use in medical education: a systematic review.

Acad Med. 2013;88(6):893-901.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828ffc23

-

Chan TM, Dzara K, Dimeo SP, Bhalerao A, Maggio LA. Social media in knowledge translation and education for physicians and trainees: a scoping review.

Perspect Med Educ. 2020;9(1):20-30.

doi:10.1007/S40037-019-00542-7

-

Colbert GB, Topf J, Jhaveri KD, et al. The social media revolution in nephrology education.

Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3(3):519-529.

doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2018.02.003

-

Chan WS, Leung AY. Use of social network sites for communication among health professionals: systematic review.

J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(3):e117117.

doi:10.2196/jmir.8382

-

Sterling M, Leung P, Wright D, Bishop TF. The use of social media in graduate medical education: a systematic review.

Acad Med. 2017;92(7):1,043-1,056.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001617

-

Rapp AK, Healy MG, Charlton ME, Keith JN, Rosenbaum ME, Kapadia MR. YouTube is the most frequently used educational video source for surgical preparation.

J Surg Educ. 2016;73(6):1,072-1,076.

doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.04.024

-

Phung A, Wright K, Choi NJS. An analysis of a family medicine residency program’s social media engagement during the 2021-2022 match cycle.

PRiMER. 2023;7:8.

doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2023.426399

-

Plack DL, Abcejo AS, Kraus MB, Renew JR, Long TR, Sharpe EE. Postgraduate-year-1 residents’ perceptions of social media and virtual applicant recruitment: cross-sectional survey study.

Interact J Med Res. 2023;12:e42042.

doi:10.2196/42042

-

Cassidy DJ, Mullen JT, Gee DW, et al. #SurgEdVidz: using social media to create a supplemental video-based surgery didactic curriculum.

J Surg Res. 2020;256:680-686.

doi:10.1016/j.jss.2020.04.004

-

Galiatsatos P, Porto-Carreiro F, Hayashi J, Zakaria S, Christmas C. The use of social media to supplement resident medical education—the SMART-ME initiative.

Med Educ Online. 2016;21(1):29332.

doi:10.3402/meo.v21.29332

-

Koontz NA, Hill DV, Dodson SC, et al. Electronic and social media-based radiology learning initiative: development, implementation, viewership trends, and assessment at 1 year.

Acad Radiol. 2018;25(6):687-698.

doi:10.1016/j.acra.2017.11.025

-

Flynn S, Hebert P, Korenstein D, Ryan M, Jordan WB, Keyhani S. Leveraging social media to promote evidence-based continuing medical education.

PLOS One. 2017;12(1):e01689620168962.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0168962

-

Maggio LA, Leroux TC, Artino AR Jr. To tweet or not to tweet, that is the question: a randomized trial of Twitter effects in medical education.

PLOS One. 2019;14(10):e0223992.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0223992

-

Yang Y-L, Xiang Z-J, Yang J-H, Wang W-J, Xu Z-C, Xiang R-L. Association of β-blocker use with survival and pulmonary function in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Eur Heart. 2020; 41(46):4,415-4,422.

doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa793

-

Guimarães H, et al. Rivaroxaban in patients with atrial fibrillation and a bioprosthetic mitral valve.

N Engl J Med. 2020;383(22):2,117-2,126.

doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2029603

-

Bouck Z, Calzavara AJ, Ivers NM, et al. Association of low-value testing with subsequent health care use and clinical outcomes among low-risk primary care outpatients undergoing an annual health examination.

JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):973-983.

doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1611

-

Guimarães H, et al. Rivaroxaban in patients with atrial fibrillation and a bioprosthetic mitral valve.

N Engl J Med. 2020;383(22):2,117-2,126.

doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2029603

-

Krittanawong C, Narasimhan B, Wang Z, et al. Association between egg consumption and risk of cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Am J of Med. 2021;134(1):76-83.E2.

doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.05.046

-

Bouck Z, Calzavara AJ, Ivers NM, et al. Association of low-value testing with subsequent health care use and clinical outcomes among low-risk primary care outpatients undergoing an annual health examination.

JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):973-983.

doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1611

-

There are no comments for this article.