Background: Remediation and early intervention for family medicine residents who experience performance problems represent a challenge for programs, faculty, and residents. Some evidence suggests that identifying those at risk for performance problems and providing support early may prevent more serious issues later in residency.

Objectives: We wanted to explore the perspectives of content experts to identify best practices for early intervention and remediation to address common challenges and create a framework for more effective and inclusive early intervention and remediation.

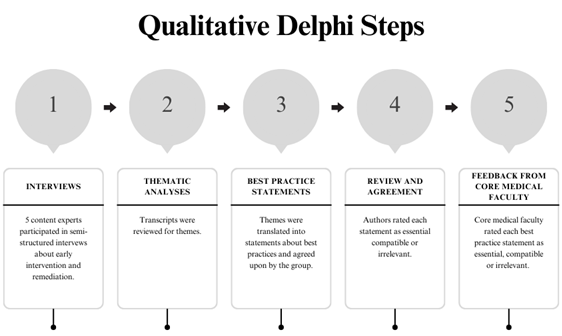

Methods: We used a Delphi approach to identify themes and best practices for early intervention and remediation, including qualitative interviews, identification of themes, clarification of essential practices, and confirmation of agreement with core medical faculty.

Results: Our qualitative interviews and Delphi methodology identified best practices in five main categories: (a) early assessment and identification, (b) feedback, (c) resident engagement, (d) intervention strategies and resources, and (e) documentation. From an initial pool of 38 recommendations, we identified a final group of 11 practices that generated broad agreement among behavioral science faculty and core medical faculty.

Conclusions: Key principles for early intervention and remediation include early skill assessment, data-driven feedback, collaborative processes, diverse resources, clear documentation, and faculty training for providing actionable feedback. While our Delphi study provided in-depth insights into various programs’ practices, it may not capture unique practices across all programs. Future research on early intervention and remediation should explore current practices, aiming for specific, collaborative, and transparent processes, with insights from experienced faculty, to enhance equity and effectiveness.

Remediation in residency is less studied than remediation in undergraduate medical education.1 Multiple factors contribute to the structure of residency being more difficult to navigate for many learners: for example, increasing general awareness of factors that contribute to learning struggles (eg, ADHD),2, 3 increased prevalence of disabilities and accommodations in the undergraduate medical school setting,4 increased access to medical careers for underrepresented populations who have suffered structural educational discrimination,5 increasing risk of mental health disorders among residents,6, 7 changes to preresidency performance measures,8 and the interruption of clinical experiences associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.9 We can reasonably assume that the demand for effective early intervention and remediation processes in residency education will increase significantly.

The process of remediation can be challenging for learners and faculty alike, taking an emotional toll on residents with performance problems and faculty physicians.10, 11 When residents experience performance problems, faculty spend an average of 19.8 hours of additional time with them to explain and implement interventions (not including time for planning, assessment, or preparation).12 In some instances, faculty turnover can be attributed to burnout from the remediation process.13 Residents who have gone through remediation have reported overwhelming emotions, negative stigma that can lead to isolation from peers, and lack of transparency that can lead to a negative remediation culture within residency.14 In some instances, residents are further stigmatized with pejorative labels (eg, “dyscompetent” or “disruptive”), further disrupting psychological safety and residency culture. 15, 16

Developing a structured, transparent process can create more predictability, consistency, and equity. Faculty and resident satisfaction with remediation programs increases when the process is clear and consistent.10 Structured, systematic, and transparent remediation processes contribute to successful remediation outcomes and learner satisfaction. 12, 13

Resident characteristics also seem to predict propensity for performance problems and academic probation. Programs refer residents who are international medical graduates, non-White, married, male, and older for remediation more frequently,17, 18 suggesting that biases may be at play. Faculty themselves may have different thresholds for gaps in medical knowledge or professionalism that can lead to differential referral for remediation. As such, a clear remediation process reduces program liability and vulnerability to accusations of bias. 19

While most programs strive for a consistent process, faculty and program personnel must overcome significant barriers to clarity, transparency, and consistency. Remediation tends to be a relatively infrequent occurrence in most residencies, with estimates ranging from 2% to 9%. 15, 18, 20, 21 Remediation is common enough to trouble most residency programs from time to time, but not common enough so that faculty develop consistent familiarity or process expertise. Further adding to the complexity of early intervention and remediation, each resident arrives with a unique set of experiences, context, and skills (eg, coping skills, support systems, personality characteristics, access to resources) that faculty take into account as they craft a resident-centered learning plan. Residency programs have varied access to tools to assess performance and clarify deficits13 in order to increase the chance of remediation success.22 Many residency programs experience shortages of personnel and other organizational resources, making devoting time and attention to formal or informal remediation difficult. Remediation efforts often require increased supervision; increased faculty time to develop and monitor plans; acquisition of learning materials; and external consultants, tutors, or evaluators.12, 22 Clear thresholds for how and when the intensity of remediation should be escalated can be difficult to develop, complicating decisions about probation, human resources involvement, and dismissal. These high-stakes decisions also tend to be associated with an increased emotional toll.

Furthermore, clarifying and organizing early intervention and prevention strategies is rare. Over the years, the literature has suggested that early intervention, prior to formal remediation, could result in better outcomes.5, 10, 14, 23, 24 Residents and programs may be able to identify subthreshold problems through self-report, exam scores, and facilitated discussions with mentors.10 Suggestions for what could be considered preventative measures have begun to emerge in the remediation literature. Early assessment of residents’ general fit for specific programs could reduce the likelihood of performance mismatches and trigger early supportive interventions.24 Explicit instruction in executive skills required for residency holds promise for easing performance problems.25 Normalizing challenges of residency and help-seeking may create an environment in which learners feel more comfortable asking for support. 5, 11 All these preliminary examples suggest that thoughtful process, early screening, and curriculum to address predictable struggles (ie, intervention strategies for residents’ skill deficits) could reduce the burden on residents and programs alike.

Because behavioral science faculty (BSF) have recently been recognized as core faculty members in family medicine residencies, they are often actively involved in the remediation process. Kalet et al26 highlighted the need for a team of interdisciplinary experts to address the diverse needs of struggling learners. BSF training and skills match well with the early intervention and remediation process. Equipped with skills to precisely identify skill deficits and underlying causes, BSF are able to effectively match performance problems with curated intervention strategies. Given their high levels of training in learning and behavior, BSF often enrich the remediation process with evidence-based approaches and learning theory to facilitate effective planning and ensure that threats to well-being are mitigated to the extent possible. Finally, BSF often are able to intervene with their knowledge of interpersonal process to facilitate effective communication, clarify boundaries, and delineate systemic factors affecting both resident performance and remediation programming. In many programs, BSF hold a formal or informal role as a supportive individual within a residency program, and they view advocacy for individuals with mental health disorders and disabilities as a professional responsibility.

In summary, early intervention and remediation is a complex and intensive process that is still somewhat ill-defined and has room for significant improvements to provide compassionate, individually tailored, and successful interventions. In this study, we aimed to identify best practices for the early intervention and remediation process that can serve as guideposts for a wide range of family medicine residency structures.

Overview

Five content experts participated in semistructured interviews about early intervention and remediation. The transcripts were reviewed for themes, which were then translated into best practice statements and agreed upon by the group. The authors rated each statement as essential, compatible, or irrelevant. Core medical faculty then provided feedback by rating the best practice statements using the same criteria. See Figure 1 for an overview of the process.

Expert Panel

At the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) Annual Conference in May 2022, the Family and Behavioral Health Collaborative met, and the authors of this article identified a need to better understand early intervention and remediation. We recruited content experts from the STFM Family and Behavioral Health Collaborative. Ten individuals from a variety of programs agreed to participate in a work group to identify best practices for early intervention and remediation of struggling residents in family medicine residency. Programs included university-based residencies, university-affiliated community-based residencies, and community-based residencies. One prospective content expert from our initial work group left family medicine education. Nine participants in the study group, the authors of this paper, served as content experts and developed the methodology, themes, and best practice recommendations for this scholarship. In this study, experts were behavioral science faculty who attended the 2022 STFM Annual Conference in Indianapolis and volunteered at the Family and Behavioral Health Collaborative to form a study group around early intervention and remediation of residents with performance problems. Each had been central to efforts to improve the early intervention and remediation process in their program. At the time of publication, our panel had a mean 16 years of experience, a range from 3 to 30 years of experience, and only one author with less than 10 years of experience in family medicine residency education.

Best Practice Thematic Analysis

This qualitative Delphi study followed a procedure detailed by Sekayi and Kennedy 27 and modified to collect detailed qualitative data from a variety of programs before identifying best practice statements (Figure 1). In the first step of the Delphi process (Figure 1 , Step 1), we interviewed five content experts using a semistructured format (Table 1). Interview questions were circulated in advance to develop consensus. Qualitative interviews were the most efficient way to ensure that content experts were able to engage in the initial step in the Delphi methodology. Five authors volunteered to participate in the interviews based on schedule availability (A.C., A.R., J.S, K.F., E.D.).

|

Describe how you identify residents who are struggling. What sources of information do you use? How do you know?

|

|

How does your program identify specific domains or skills that will require additional support, accommodations, or intervention? In which domains do residents most commonly struggle? For which domains does your program provide the best/most efficacious resources? For which domains does your program feel less confident about intervening?

|

|

What are the steps that your program may take in the early intervention and remediation process (from recognition to dismissal)? Who are the key stakeholders that are most involved at each step?

|

|

How do you involve residents in the remediation process? How does resident involvement change depending on escalation or severity of concern?

|

|

Based on your experiences, what recommendations would you give for best practices for programs for when they encounter family medicine residents with difficulties?

|

Item Identification

The transcripts were deidentified by C.H. and subsequently coded by A.C., J.S., K.F., and A.R. Authors did not review their own transcripts when identifying themes. C.H. reviewed the final themes (Table 2) agreed upon by A.C., A.R., J.S., K.F., E.D. and J.A. and created statements about best practices for subsequent review (Figure 1, Step 2). This process resulted in a best practices questionnaire (Table 3) with 38 statements derived from thematic analysis (Figure 1 , Step 3).

|

Theme

|

Recommendation

|

Thematic material

|

Sample

quote

|

|

Early assessment and identification

|

Use a broad array of sources to evaluate resident skills and performance.

|

ITE scores, OSCEs, simulation lab, patient surveys, staff surveys, preceptor feedback, EMR note completion rates, feedback from senior residents, observations from program coordinator, resident concerns discussed in faculty meetings

|

“During orientation we do a mock in-training exam and we do some OSCEs of skills that . . . we’ve learned that our residents have not gotten. . . . We use those two as a baseline kind of landmark for people who need . . . an individualized education plan.”

|

|

Feedback

|

Establish a structure of performance review and advising meetings. Develop more opportunities for struggling learners to elicit feedback, seek support, and develop skills.

|

Schedule advisor meetings on at least a quarterly basis; use a checklist of activities/questions to be completed during each meeting to provide consistency and predictability; provide training for residents on eliciting effective feedback.

|

“Residents are supposed to meet with their advisor every month . . . and at that [time] the advisor [is] supposed to review evaluations with the resident, talk about their . . . individualized learning plan.”

|

|

Resident engagement

|

Destigmatize help-seeking behavior by normalizing challenges during residency, modeling vulnerability, and creating a transparent, accessible process for seeking help.

|

Develop a collaborative process through first holding an informal discussion with the advisor to discuss concerns/feedback, elicit resident perspective and reactions, balance emotional support with corrective feedback, and obtain resident input for next steps/plan.

|

“There’s this tension between giving clear feedback about performance and really being able to address residents’ feelings of vulnerability in the process.”

|

|

Intervention strategies and resources

|

Identify specific measurable steps for meaningful improvement when creating intervention/remediation plans.

|

Explain processes in the program manual and review when the intervention plan is initiated and every time progress is assessed; faculty should clearly state their role in the moment (eg, skills coach vs evaluator).

|

“We do expect the advisor and the resident to meet regularly—depending on what we decide ‘regularly’ is—to make sure that the things that we’re setting in place . . . are happening or . . . maybe we need to regroup and change this a little bit.”

|

|

Documentation

|

For any resident on the early intervention and remediation continuum, document plans clearly, including specific strategies, time-limited evaluation periods, and next steps if performance does not improve (ie, escalation).

|

Document meeting dates, concerns discussed, context/classification of struggle (medical knowledge vs professionalism), SMART goals, responsibilities of resident/faculty/outside providers, place in the intervention process, next review date, next steps depending on improvement or failure to progress; demonstrate transparency through sharing notes/plan with the resident.

|

“[We] come up with a proposed plan . . . share it with the resident, tweak it, and then we all sign it and put it in play.”

|

|

Statement

#

|

Item

|

Score

|

|

1

|

Use a broad array of sources to evaluate resident skills and performance (eg, direct observation, mock ITE, OSCE, presentations, patient surveys, staff surveys, preceptor feedback, chart completion rates, completed documentation, feedback from senior residents, self-assessment, program coordinator, informal observation, CCC review)

|

18

|

|

2

|

Destigmatize help-seeking behavior by normalizing challenges during residency, modeling vulnerability, and creating a transparent, accessible process for accessing help.

|

18

|

|

3

|

Identify specific measurable steps for meaningful improvement (eg, SMART goals, milestone-linked thresholds) when creating intervention/remediation plans.

|

18

|

|

4

|

Create an orderly, transparent process for early intervention and remediation that identifies specific steps and program personnel and roles at each step.

|

18

|

|

5

|

For any resident on the early intervention and remediation continuum, document plans clearly, including specific strategies, time-limited evaluation periods, and next steps if performance does not improve (ie, escalation).

|

18

|

|

6

|

Explicitly identify key early experiences in residency (eg, inpatient service) that provide data about skills and formalize a consistent system for collecting that data.

|

17

|

|

7

|

Incorporate faculty development in giving feedback and evaluating performance regularly.

|

17

|

|

8

|

Train faculty to document concerns about resident performance.

|

17

|

|

9

|

Begin with a collegial conversation between the resident and a familiar faculty member (eg, advisor) to elicit resident reactions to concerns and assess resident needs.

|

17

|

|

10

|

Keep a predictable schedule of performance review and advising meetings, and create more opportunities for struggling learners to elicit feedback, seek support, and develop skills.

|

17

|

|

11

|

Once a plan is in place, elicit performance feedback from faculty regularly to gain insight on progress and need for further intervention and escalation.

|

17

|

|

12

|

Elicit self-assessment early and routinely including residents’ perceived strengths and areas for growth.

|

16

|

|

13

|

Develop opportunities for direct observation of clinical encounters and interpersonal interactions to identify problems.

|

16

|

|

14

|

Structure CCC meetings to aggregate data and identify key components of resident functioning.

|

16

|

|

15

|

Clarify language used for specific steps in the process of early intervention and remediation all the way through probation and dismissal. Make sure faculty and key stakeholders (eg, residency affairs, human resources) are involved.

|

16

|

|

16

|

Recognize the important difference between skill development and serious lapses of professionalism and differentiate the process accordingly.

|

16

|

|

17

|

Ensure that mental health and disability resources are in place.

|

16

|

|

18

|

Design experiences early in residency so that core faculty, senior residents, staff, and community faculty can assess performance.

|

15

|

|

19

|

Create routine opportunities for faculty to share impressions of resident performance formally and informally, including during meetings.

|

15

|

|

20

|

Create formal and informal means for residents to self-identify needs and struggles.

|

15

|

|

21

|

Explicitly engage residents from the beginning about what to do if they are struggling or if their performance is not as good as they want it to be.

|

15

|

|

22

|

Use milestone domains to characterize patterns in performance as they relate to residents’ skills.

|

14

|

|

23

|

Develop PGY-specific performance standards linked to milestones, key resident EPAs, and responsibilities.

|

14

|

|

24

|

Create opportunities for faculty to identify specific domains when giving feedback in any environment.

|

14

|

|

25

|

Use a team approach with specific personnel assigned to monitor progress and maintain follow-up on plans.

|

14

|

|

Statement #

|

Item

|

Score

|

|

26

|

When documenting specific plans to address performance, include residents in the process and create shared written documentation with interventions, goals, and evaluation periods.

|

14

|

|

27

|

Once residents have a formal plan, empower the advisor to advocate for the resident in a mentoring role, while another faculty serves as the leader of evaluation and intervention.

|

14

|

|

28

|

Create a process that accounts for different perspectives between faculty and between faculty and residents, including strategies for checking bias.

|

14

|

|

29

|

Create a process that respects residents as whole people and takes into account that frequent scrutiny leads to a sense of vulnerability.

|

14

|

|

30

|

Perform regular faculty development to support skills in feedback and engaging residents effectively.

|

14

|

|

31

|

Monitor readily available archival data, including chart completion, notes, and time-sensitive tasks.

|

13

|

|

32

|

Utilize CCC meetings to identify key domains of concern.

|

13

|

|

33

|

Anticipate the need for domain-specific remediation by developing domain-specific tools for intervention and remediation.

|

13

|

|

34

|

Ensure that faculty have clarity to deliver micro-level feedback for domain-specific skills when intervention is in place.

|

13

|

|

35

|

Link junior residents who have performance problems with high-performing seniors to develop practical skills (eg, organization, presentations, well-being).

|

12

|

|

36

|

No matter the stage in the process, elicit resident reactions to the intervention and follow-up strategies.

|

12

|

|

37

|

Begin with the lowest stakes, least threatening step possible for early intervention.

|

11

|

|

38

|

Acknowledge systemic factors and predictable challenges that could provide information about domain-specific skills.

|

8

|

Delphi Survey Process

All nine content experts rated each statement as essential (2), compatible (1), or irrelevant (0) for early intervention and remediation best practices (Figure 1 , Step 4). Item scores were used to identify the 11 most essential statements (Table 4), with five items that all authors agreed were essential and six items that all but one author rated as essential.

|

Faculty #

|

Item

|

Score

|

|

11

|

Once a plan is in place, elicit performance feedback from faculty regularly to gain insight on progress and need for further intervention and escalation.

|

34

|

|

1

|

Use a broad array of sources to evaluate resident skills and performance (eg, direct observation, mock ITE, OSCE, presentations, patient surveys, staff surveys, preceptor feedback, chart completion rates, completed documentation, feedback from senior residents, self-assessment, program coordinator, informal observation, CCC review).

|

34

|

|

5

|

For any resident on the early intervention and remediation continuum, document plans clearly, including specific strategies, time-limited evaluation periods, and next steps if performance does not improve (ie, escalation).

|

33

|

|

2

|

Destigmatize help-seeking behavior by normalizing challenges during residency, modeling vulnerability, and creating a transparent, accessible process for accessing help.

|

33

|

|

8

|

Train faculty to document concerns about resident performance.

|

32

|

|

10

|

Keep a predictable schedule of performance review and advising meetings, and create more opportunities for struggling learners to elicit feedback, seek support, and develop skills.

|

31

|

|

7

|

Incorporate faculty development in giving feedback and evaluating performance regularly.

|

31

|

|

4

|

Create an orderly, transparent process for early intervention and remediation that identifies specific steps and program personnel and roles at each step.

|

31

|

|

3

|

Identify specific measurable steps for meaningful improvement (eg, SMART goals, milestone-linked thresholds) when creating intervention/remediation plans.

|

31

|

|

17

|

Ensure that mental health and disability resources are in place.

|

30

|

|

9

|

Begin with a collegial conversation between the resident and a familiar faculty member (eg, advisor) to elicit resident reactions to concerns and assess resident needs.

|

30

|

|

6

|

Explicitly identify key early experiences in residency (eg, inpatient service) that provide data about two skills and formalize a consistent system for collecting that data.

|

29

|

Best Practice Endorsements

We sought the feedback of core medical faculty in each of our programs to determine broader agreement for best practices that we had identified as essential (Figure 1 , Step 5). Seventeen faculty responded to the survey, including three program directors, four associate program directors, and 10 core faculty. All respondents were MDs and DOs with a range of experience (one with 1 year or less, four with 2 years of experience, five with 3–5 years of experience, two with 5–8 years of experience, and five with 9 or more years of experience). Core medical faculty rated each statement using the same response options used for the Delphi survey process described earlier (essential [2], compatible [1], and irrelevant [0] for early intervention and remediation best practices).

This study was reviewed and classified as exempt by the Western Michigan Home Stryker MD School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Thematic Analysis

Review of transcripts from semistructured interview questions yielded themes in five main categories: (a) early assessment and identification, (b) feedback, (c) resident engagement, (d) intervention strategies and resources, and (e) documentation. In general, our content experts agreed that a wide array of data about skills and performance should be collected early in residency to offer more opportunities to identify problems and provide support. Interviews with content experts also revealed themes about engaging residents early and eliciting residents’ perceptions of performance problems. Thematic analysis indicated that clear feedback is a necessary component of improved resident performance, facilitating clarity of expectations. Content experts discussed familiarity with a range of intervention strategies depending on the nature of performance problems. Finally, thematic analysis indicated that careful documentation is an important component of early intervention and remediation to monitor progress, to understand when strategies should change or intensify, and to record performance thresholds for advancement, probation, and dismissal. Please see Table 2 for themes, examples, and sample quotations.

Delphi Questionnaire Results

Our Delphi questionnaire revealed a range of consensus ratings about best practices for each of the 38 items, from 8 to 18. Table 3 contains items and consensus ratings sorted according to score with those items scoring an 18 representing perfect agreement that the recommendation is essential for remediation. Five items were rated as essential by all content experts. Six additional items were rated as essential by eight out of nine content experts.

Best Practice Endorsements

On the subset of items rated as most essential by content experts, core medical faculty displayed substantive agreement about their importance for early intervention and remediation (Table 4). For this subset of essential items, scores ranged from perfect agreement (34) to less agreement (29). None of the items in the final subset received a rating of 0 from any of the core medical faculty.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This project was designed to develop a road map for best practices in early intervention and remediation with family medicine residents. The overall goal was to identify processes for improving existing remediation programs and to develop new programs that emphasize collaboration between residents and program personnel. Recommendations contained in Table 4 represent essential practices identified and agreed upon by behavioral science content experts and a cohort of medical faculty at affiliated programs.

Our recommendations could be summarized effectively by the following principles:

-

Family medicine residency programs should assess residents’ skills early and often.

-

Programs should actively collect performance data and disseminate actionable feedback.

-

Engaging residents early in a collaborative process designed to elicit their perspective can help identify relevant needs and context.

-

A system that incorporates key stakeholders, diverse tool kits, and resources designated for specific domains of functioning will serve residents and programs more effectively.

-

Clear documentation promotes accountability, facilitates follow-through, and provides vital thresholds for both advancement and intensification of interventions.

One key overall message reflected in the thematic analysis is the importance of being intentional and developing an organized, transparent approach to remediation. The panel recommended that residents and faculty approach early intervention and remediation as a normal part of the learning process, with a collaborative process that is based on fair, objective evaluations. Programs should proactively train faculty to provide clear feedback that includes actionable steps for skill development. All relevant meetings, feedback, and interventions should be part of an organized plan that is well-documented. Resident mental health needs and unique accommodations should be taken into account, and these should also be documented.

We must recognize inherent limitations of this methodology. While this Delphi-type study allowed for depth and reflection on practices in a variety of programs, many programs have unique practices that would not be captured in this study. The data came from a relatively small number of BSF; and programs and this methodology cannot identify all the nuances of the remediation processes conducted by various programs around the country. The design of the study did not include before and after data, and thus limited us from predicting effectiveness of the method. Because these results are limited in their generalizability, programs should certainly take each individual resident’s needs into account when developing early intervention and remediation programs. While the results of this study offer guiding principles, we encourage faculty to continue to network with other programs to learn more about how to address early intervention and remediation.

Future research on early intervention and remediation should further explore current remediation practices across family medicine residency programs. Faculty should strive to develop early intervention and remediation processes that are specific, collaborative, transparent, and grounded in existing theories on effective remediation. This study showed that experienced BSF are in agreement on the important factors in this area and that surveying experienced core faculty for their ideas on this topic has value. Further studies on early intervention and remediation methods could lead to greater standardization of these processes and thus enhance fairness and equity. Further studies would enrich our knowledge and promote more effective strategies for remediation that could be tailored to a variety of environments.

References

-

Frazier W, Wilson SA, D’Amico F, Bergus GR. Resident remediation in family medicine residency programs: a CERA survey of program directors.

Fam Med. 2021;53(9):773-778.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.546572

-

Cadick A, Haymaker C, McGuire N. This is my learner, not my patient: addressing concerns in learners with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Int J Psychiatry Med. 2022;57(5):434-440.

doi:10.1177/00912174221116730

-

Abdelnour E, Jansen MO, Gold JA. ADHD diagnostic trends: increased recognition or overdiagnosis? Mo Med. 2022;119(5):467-473.

-

Meeks LM, Jain NR, Moreland C, Taylor N, Brookman JC, Fitzsimons M. Realizing a diverse and inclusive workforce: equal access for residents with disabilities.

J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(5):498-503.

doi:10.4300/JGME-D-19-00286.1

-

Chou CL, Kalet A, Costa MJ, Cleland J, Winston K. Guidelines: the dos, don’ts and don’t knows of remediation in medical education.

Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8(6):322-338.

doi:10.1007/S40037-019-00544-5

-

Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

JAMA. 2015;314(22):2,373-2,383.

doi:10.1001/jama.2015.15845

-

Pereira-Lima K, Meeks LM, Ross KET, et al. Barriers to disclosure of disability and request for accommodations among first-year resident physicians in the US.

JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(5):e239981.

doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.9981

-

Spring L, Robillard D, Gehlbach L, Simas TAM. Impact of pass/fail grading on medical students’ well-being and academic outcomes.

Med Educ. 2011;45(9):867-877.

doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.03989.x

-

Dedeilia A, Papapanou M, Papadopoulos AN, et al. Health worker education during the COVID-19 pandemic: global disruption, responses and lessons for the future—a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Hum Resour Health. 2023;21(1):13.

doi:10.1186/s12960-023-00799-4

-

Wu JS, Siewert B, Boiselle PM. Resident evaluation and remediation: a comprehensive approach.

J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(2):242-245.

doi:10.4300/JGME-D-10-00031.1

-

Krzyzaniak SM, Wolf SJ, Byyny R, et al. A qualitative study of medical educators’ perspectives on remediation: adopting a holistic approach to struggling residents.

Med Teach. 2017;39(9):967-974.

doi:10.1080/0142159X.2017.1332362

-

Guerrasio J, Garrity MJ, Aagaard EM. Learner deficits and academic outcomes of medical students, residents, fellows, and attending physicians referred to a remediation program, 2006-2012.

Acad Med. 2014;89(2):352-358.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000122

-

Guerrasio J, Brooks E, Rumack CM, Aagaard EM. The evolution of resident remedial teaching at one institution.

Acad Med. 2019;94(12):1,891-1,894.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002894

-

Krzyzaniak SM, Kaplan B, Lucas D, Bradley E, Wolf SJ. Unheard voices: a qualitative study of resident perspectives on remediation.

J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(4):507-514.

doi:10.4300/JGME-D-20-01481.1

-

-

Barnhoorn PC, van Mook WNKA. Professionalism or professional behaviour: no reason to choose between the two.

Med Educ. 2015;49(7):740-740.

doi:10.1111/medu.12650

-

Yao DC, Wright SM. National survey of internal medicine residency program directors regarding problem residents.

JAMA. 2000;284(9):1,099-1,104.

doi:10.1001/jama.284.9.1099

-

Guerrasio J, Brooks E, Rumack CM, Christensen A, Aagaard EM. Association of characteristics, deficits, and outcomes of residents placed on probation at one institution, 2002-2012.

Acad Med. 2016;91(3):382-387.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000879

-

Lefebvre C, Williamson K, Moffett P, et al. Legal considerations in the remediation and dismissal of graduate medical trainees.

J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(3):253-257.

doi:10.4300/JGME-D-17-00813.1

-

Dupras DM, Edson RS, Halvorsen AJ, Hopkins RH Jr, McDonald FS. “Problem residents”: prevalence, problems and remediation in the era of core competencies.

Am J Med. 2012;125(4):421-425.

doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.12.008

-

Bhatti NI, Ahmed A, Stewart MG, Miller RH, Choi SS. Remediation of problematic residents—a national survey.

Laryngoscope. 2016;126(4):834-838.

doi:10.1002/lary.25599

-

Katz ED, Dahms R, Sadosty AT, Stahmer SA, Goyal D; CORD-EM Remediation Task Force. Guiding principles for resident remediation: recommendations of the CORD Remediation Task Force.

Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(suppl 2):S95-S103.

doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00881.x

-

Domen RE. Resident remediation, probation, and dismissal basic considerations for program directors.

Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;141(6):784-790.

doi:10.1309/AJCPSNPAP5R5NHUS

-

Rumack CM, Guerrasio J, Christensen A, Aagaard EM. Academic remediation: why early identification and intervention matters.

Acad Radiol. 2017;24(6):730-733.

doi:10.1016/j.acra.2016.12.022

-

van Mook WNKA, de Grave WS, Wass V, et al. Professionalism: evolution of the concept.

Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20(4):e81-e84.

doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2008.10.005

-

Kalet A, Guerrasio J, Chou CL. Twelve tips for developing and maintaining a remediation program in medical education.

Med Teach. 2016;38(8):787-792.

doi:10.3109/0142159X.2016.1150983

-