Background and Objectives: Academic advancement requires scholarship productivity. Faculty underrepresented in medicine (URiM) face unique challenges that hinder their scholarship productivity. We introduce the term “scholarship delay” as a phenomenon that affects early career academic faculty and describe what is known in the literature about this phenomenon among URiM faculty.

Methods: For the narrative review, we searched PubMed between November 2023 and September 2024 for articles describing URiM publication productivity. Out of 2,351 initial results, we included articles published between 2000 and 2024 and produced in the United States. After excluding articles based on title and abstract content, we thoroughly examined 43 articles and selected 33 for this review. We included primary research articles including survey studies, literature reviews, and demographic data analyses.

Results: Factors that mediate scholarship delay exist prior to one becoming a faculty member; URiM faculty and trainees are disproportionately affected. Several mediating factors cause scholarship delay, including lack of strong research mentorship and sponsorship, lack of protected time toward scholarly pursuits, and competing clinical responsibilities. Additionally, URiM faculty can suffer from unsupportive institutional cultures that lack resources or infrastructure to help them thrive in the production of scholarly work.

Conclusions: Scholarship delay is a significant and underreported phenomenon that affects early career URiM academic faculty and trainees. Solutions that may help mitigate this issue include rectifying barriers at the individual and institutional level prior to and during one’s journey as a faculty member.

As faculty advance in their academic medicine careers, several factors impact their scholarship productivity. The criteria for faculty advancement—advancing in rank or obtaining leadership titles—is variable by institution.1-4 Advancement differs depending on specialty and whether faculty are on tenure or nontenure tracks.5, 6 Furthermore, the resources available to support scholarship are variable.7, 8 Ultimately, faculty’s understanding of the advancement process may impact their prioritization of scholarship. 9-11

Faculty who are underrepresented in medicine (URiM) are not advancing at rates equal to their colleagues in academic medicine.12-14 Despite improvements in representation, the number of URiM faculty in academic medicine is still insufficient.15, 16 Furthermore, the number who achieve professor rank is even smaller.17, 18 URiM faculty often are hired as junior faculty with limited support to advance in rank.14 They are often on clinical tracks, which are slower for promotion.19 Despite their hired role, URiM faculty also are more likely to have additional responsibilities, such as leading subcommittees and assuming volunteer and advocacy roles that benefit minority communities.20, 21 Although much needed in our society, these commitments are less often evaluated in the promotional process compared to research and publications.22 Scholarly productivity depends on institutional support and expectations. Due to this variability, the time to rank promotion also may vary in years.23, 24 Petersdorf et al demonstrated that URiM faculty are promoted 3 to 7 years later than their non-URiM counterparts.25 A similar disparity was noted by Fang et al, with URiM faculty “lagging” in rank promotion, securing tenure tracks and status, compared to their non-URiM counterparts. 14

We introduce the term “scholarship delay” to describe the lack of or minimal production of publications in the early career years of an academic medicine faculty member. We believe that scholarship delay and the factors that impact scholarly productivity play a critical role in URiM faculty career advancement. In this paper, we aim to describe what is known in the literature about scholarship delay in URiM faculty and how URiM faculty are disproportionately affected. We emphasize publications in our proposed definition of scholarship delay because we hypothesize that this specific form of scholarship is where a disparity among URiM faculty is found. We also provide solutions for URiM faculty and their chairs to guide their scholarly path toward successful promotion, tenure, and advancement in their academic career.

For our narrative review, a medical librarian (D.B.) conducted searches within PubMed between November 2023 and September 2024. Articles were eliminated if they were not in English, if they discussed education outside of the United States, if they were no longer available, if they did not discuss medical education or academic medicine, if they did not discuss publication productivity, if they did not discuss URiM groups, or if they had already been selected during a prior search.

We searched for the terms “URiM” and “underrepresented,” which are established in the literature. We did not search for specific identities as they relate to race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, disability, or other unique groups. We chose articles that focused on academic medicine in the United States because the expertise of the authors performing the review is exclusive to the United States. Furthermore, we used PubMed because its publication trend on URiM faculty development recently has demonstrated positive growth.20 Our search included articles published between 2000 and 2024.

Table 1 summarizes our search strategy, exclusion criteria, and article selection with initial search results. D.B. reviewed titles and abstracts for relevance and eliminated articles based on exclusion criteria set by the authors. The 43 articles identified were then first reviewed by two authors (L.A. and S.O.) to verify relevance. These articles included qualitative survey studies, literature reviews, intervention advice, intervention case studies, or demographic data analysis. The articles next were thoroughly examined by all authors to ensure the articles identified and described the problem of scholarship delay or identified interventions and potential solutions. A total of 33 articles ultimately were included in this review. The 10 eliminated articles were removed because they did not provide demographic data by ethnicity/race; they focused broadly on academic medicine success, but did not specifically address scholarship productivity; they mentioned the problem of scholarship delay in URiM faculty, but did not describe it or provide interventions or solutions.

|

Search strategy

|

Results

|

Eliminated

|

In review

|

Reviewed via

|

Exclusion criteria

|

Article research types

|

|

Early career URiM publication

|

2

|

0

|

2

|

Full text review

|

No exclusions

|

Survey study

|

|

URiM scholarship

|

14

|

9

|

5

|

Abstract review

|

Did not discuss medical education/academic medicine; did not discuss publication productivity; duplicate article in another search

|

Survey study; literature review; demographic data analysis

|

|

URiM publication

|

27

|

21

|

6

|

Abstract review

|

Did not discuss medical education/academic medicine; did not discuss publication productivity; duplicate article in another search

|

Survey study; intervention case study; literature review; demographic data analysis

|

|

Early career scholarship

|

345

|

341

|

4

|

Title review

|

Article no longer available (possible retraction); research conducted outside the United States; did not discuss medical education/academic medicine; did not discuss publication productivity; did not discuss URiM or underrepresented groups; duplicate article in another search

|

Survey study; intervention case study;

|

|

Early career publication

|

1432

|

1427

|

5

|

Title review

|

Not available in English; research conducted outside the United States; did not discuss medical education/academic medicine; did not discuss publication productivity; did not discuss URiM or underrepresented groups; duplicate article in another search

|

Survey study; intervention case study; invited commentary

|

|

Early career diversity publication

|

132

|

127

|

5

|

Title review

|

Research conducted outside the United States; did not discuss medical education/academic medicine; did not discuss publication productivity; did not discuss URiM or underrepresented groups; duplicate article in another search

|

Survey study; intervention case study; invited commentary

|

|

Underrepresented scholarship

|

285

|

282

|

3

|

Title review

|

Did not discuss medical education/academic medicine; did not discuss publication productivity; duplicate article in another search

|

Intervention case study; invited commentary,

|

|

Underrepresented early career publication

|

59

|

53

|

6

|

Abstract review

|

Research conducted outside the United States; did not discuss medical education/academic medicine; did not discuss publication productivity; duplicate article in another search

|

Survey study; intervention case study; literature review; invited commentary

|

|

Underrepresented publication productivity

|

9

|

7

|

2

|

Full text review

|

Did not discuss medical education/academic medicine; duplicate article in another search

|

Demographic data analysis; literature review

|

|

URiM promotion

|

46

|

41

|

5

|

Abstract review

|

Did not discuss medical education/academic medicine; did not discuss publication productivity; duplicate article in another search

|

Survey study; literature review, invited commentary; intervention case study; demographic data analysis

|

|

Total

|

2,351

|

2,308

|

43

|

|

|

|

|

Reviewed by authors

|

43

|

10

|

33

|

Full text review

|

Did not provide demographic information by race/ethnicity; did not address or describe scholarship delay; did not provide interventions

|

Survey study; literature review, invited commentary; intervention case study; demographic data analysis

|

The literature review identified several factors that affect academic medicine faculty advancement in general as well as factors that specifically affect URiM faculty. We highlight key articles that describe the problem of scholarship delay among URiM faculty.

Variability in Criteria for Faculty Advancement

Advancement in academic medicine may include rank promotion or attainment of leadership roles such as program director, dean, or departmental chair. Although compensation differs by institution and often is impacted by clinical productivity, a higher academic rank and leadership title may increase a faculty member’s salary.26-28 Though many early career faculty hold leadership roles, scholarly productivity and rank are not always associated with those roles. 29-31 Nonetheless, rank promotion has traditionally been equated with professional success, yielding greater access to professional opportunities for faculty.4, 10 URiM faculty who get selected for leadership positions early in their careers run the risk of a pseudo-leadership experience, in which they are given a title because of the racial or ethnic diversity that they bring but are advanced too early in their career without the necessary training and support to effectively fulfill that role as well as their other faculty priorities, including scholarship. 32

Although rank promotion criteria may vary widely across institutions, an important criterion for many institutions is scholarship productivity.1, 2 Institutional promotion criteria that are publicly available mention other variables, such as years in current rank, teaching evaluations, institutional service, letters of recommendation, and faculty vote. Variability in criteria means that some subjectivity may be necessary in interpreting promotion guidelines and an applicant’s dossier. For clinician-educators, scholarship usually is assessed by their number of regional or national presentations, curricula developed, and peer-reviewed publications.3, 8 However, publications are often more heavily weighted than presentations and are further stratified by order of authorship, journal reputation, and citation impact.2

Faculty Advancement Unique to Specialty and Track

Although scholarly activity is required by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, publications are not as common among academic generalists compared to academics in medical and surgical subspecialties.5, 33 In addition, early career faculty, with fewer than 7 years of experience, may not produce publications due to competing commitments such as clinical and administrative tasks, and limited supported time for scholarly projects or research.9 The importance of scholarship varies within medical specialties. Scholarship in academic primary care specialties is prioritized lower than it is in other subspecialties. 5, 6 Blazey-Martin and colleagues found a strong connection between scholarship and promotion patterns, with longitudinal follow-up after 17 years revealing that academic generalists were less likely to have research productivity and to have been promoted to full professors.5

Depending on the specialty that URiM students and residents enter, their research productivity in training could potentially hinder their academic advancement to varying levels. For example, in the field of ophthalmology where research is heavily weighted, Sun and their team retrospectively reviewed one program’s residency applications over 3 years and recorded each applicant’s scholarly products.34 Then, they analyzed the statistical relationship between demographics and the number and type of scholarly products. They found that URiM applicants had fewer first authorships, had fewer publications in ophthalmology, and were less likely to take time away from training for research.34 Entering a subspecialty as a URiM faculty does not necessarily protect against scholarship delay. Even before entering a faculty rank, those who are URiM are at a disadvantage. Therefore, the presence of seasoned faculty mentors is needed to help steer junior faculty and trainees along the path to scholarship productivity.

Understanding the Track and Advancement Process for Promotion

There is a general lack of education on the tenure promotion process, mentorship, and support for those in academic medicine, particularly depending on the specialty.23 Tenure is the ultimate goal in academic rank advancement. Although tenure varies by institution, it usually protects faculty from unwarranted dismissal and strengthens their academic freedom and financial security.35 However, the number of nontenure track faculty far outnumber those of tenure track faculty, 70% to 30%, respectively. This gap may suggest a lack of interest in scholarly work among nontenured faculty. Yet, nontenure track faculty have robust involvement in quality improvement projects, conference presentations, and scholarly writing. 11

Precareer Opportunities and Preparation for URiM Faculty

Using de-identified data of medical school matriculants, graduated residents, and full-time faculty, Jeffe et al applied statistical modeling to study the mediating effects of 11 variables on the relationship between race, ethnicity, and full-time faculty appointments. Among these variables were research experience in college and residency, standardized test scores, and specialty choice.36 The researchers found that struggles in academic achievement in the basic sciences and in standardized tests for URiM students in higher education hinders scholarly productivity.36 Students who need to remediate do not have time to participate in extracurricular activities such as research. Formal research program participation contributes to academic success in medical training (eg, passing courses), increases the likelihood of entering academics, and leads to publishing literature.36

Nonexistent research apprenticeship or mentorship prior to reaching faculty rank is yet another factor that impacts URiM physicians. URiM learners are lacking among those engaged in research within college, medical school, and residency.36 Moreover, more research opportunities and mentorship are available at university programs compared to community programs.37, 38

Although women are not underrepresented in medicine, they are underrepresented in publication productivity and tenure status.23, 39 Inequities are present as early as the undergraduate level for women physician-scientists, with reports of “higher number of research experiences than men but a significantly lower number of publications.”38 Fewer research opportunities are available at some institutions, such as institutions not within the National Institutes of Health top 40 research-funded medical schools. Interestingly, fewer women and URiMs graduate from top research-ranked medical schools.38 This finding correlates with fewer publications and the disparity between the number of women compared to men in tenure.34 Furthermore, the research contributions from women and URiM physicians are less valued than those from other groups. When compared to men, “women are 59% less likely to receive research awards”; and when compared to non-URiM students, “URiM students are 82% less likely to receive research awards.”38 In summary, while separate, both women and URiMs are underrepresented in the number of publications and tenure positions; also noteworthy is that individuals who identify as both a woman and URiM are severely disadvantaged.

Faculty Support, Mentorship, and Professional Development Opportunities

For URiM faculty, scholarship and mentorship are crucial in the early stages of their career when they are developing their professional identity.40 Using scoping review methodology and data extraction of primary research and commentaries, Russel et al described “pathways with potholes” that URiM physicians uniquely face in their academic careers.41 The potholes include hostile work environments, unsupportive climates, racial discrimination, and the minority tax, all of which detrimentally affect retention and scholarly pursuits.21, 41 These factors also affect other minority groups in medicine and individuals with intersectional identities.38

Primary care scholarship can be perceived as less important than other pursuits, leading to less funding and mentorship.11 Moreover, publications take extensive time to complete, and not all submissions are accepted. Faculty may be discouraged from resubmitting their work. 42 For clinician-educators who see patients and teach trainees, finding time can be challenging. Faculty with more protected time for scholarship have higher promotion rates than those with more clinical time.7

To offset scholarship delay, mentors help steer URiM early career faculty toward meaningful opportunities. Esslinger et al highlighted the importance of mentorship and sponsorship from “high-value mentors” with institutional power and authority.43 Mentorship and sponsorship can help early career faculty to effectively use administrative or supported time. The Program to Launch Underrepresented in Medicine Success at Indiana University School of Medicine entails a 2-year commitment where faculty receive a 10% effort allotment to engage in scholarship and leadership coaching. The initial cohort met the requirements for their 3-year review, promotion, or tenure within 3 years of completing the program.44 Moreover, Jacobs et al demonstrated that faculty with more protected time for scholarship, particularly clinic-based faculty, were promoted to associate and full professor faster.7 For early career investigators and trainees, grant-writing mentorship increases publication productivity.45 However, even with grant-writing mentorship, a gap exists between the publication productivity of URiM investigators and that of their well-represented counterparts. In fact, the gap is wider than the gap that exists among investigators who do not have any mentorship.45 Gutierrez et al noted that pursuing projects concurrently rather than sequentially was vital for building a strong file for promotion and tenure. 45

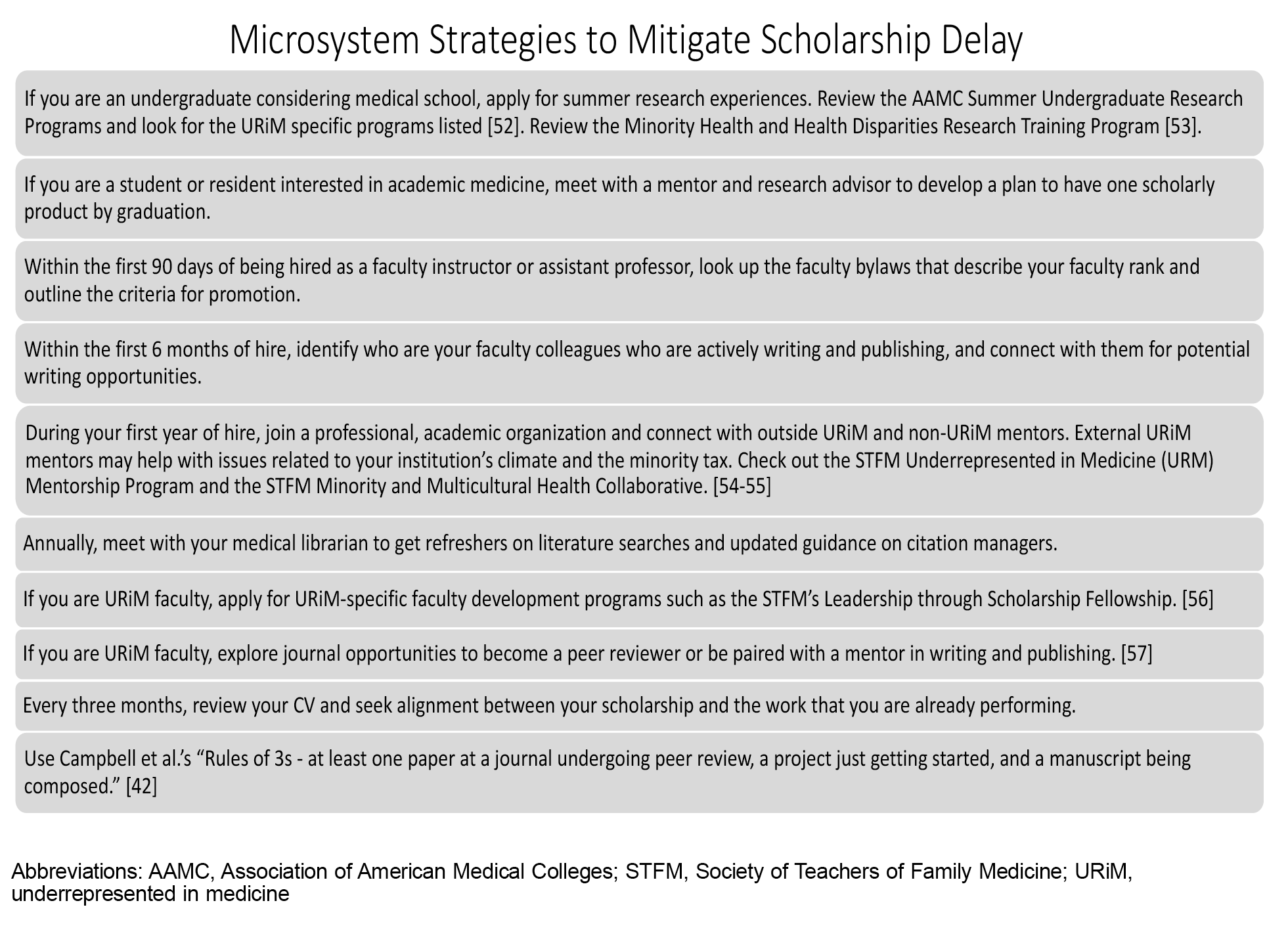

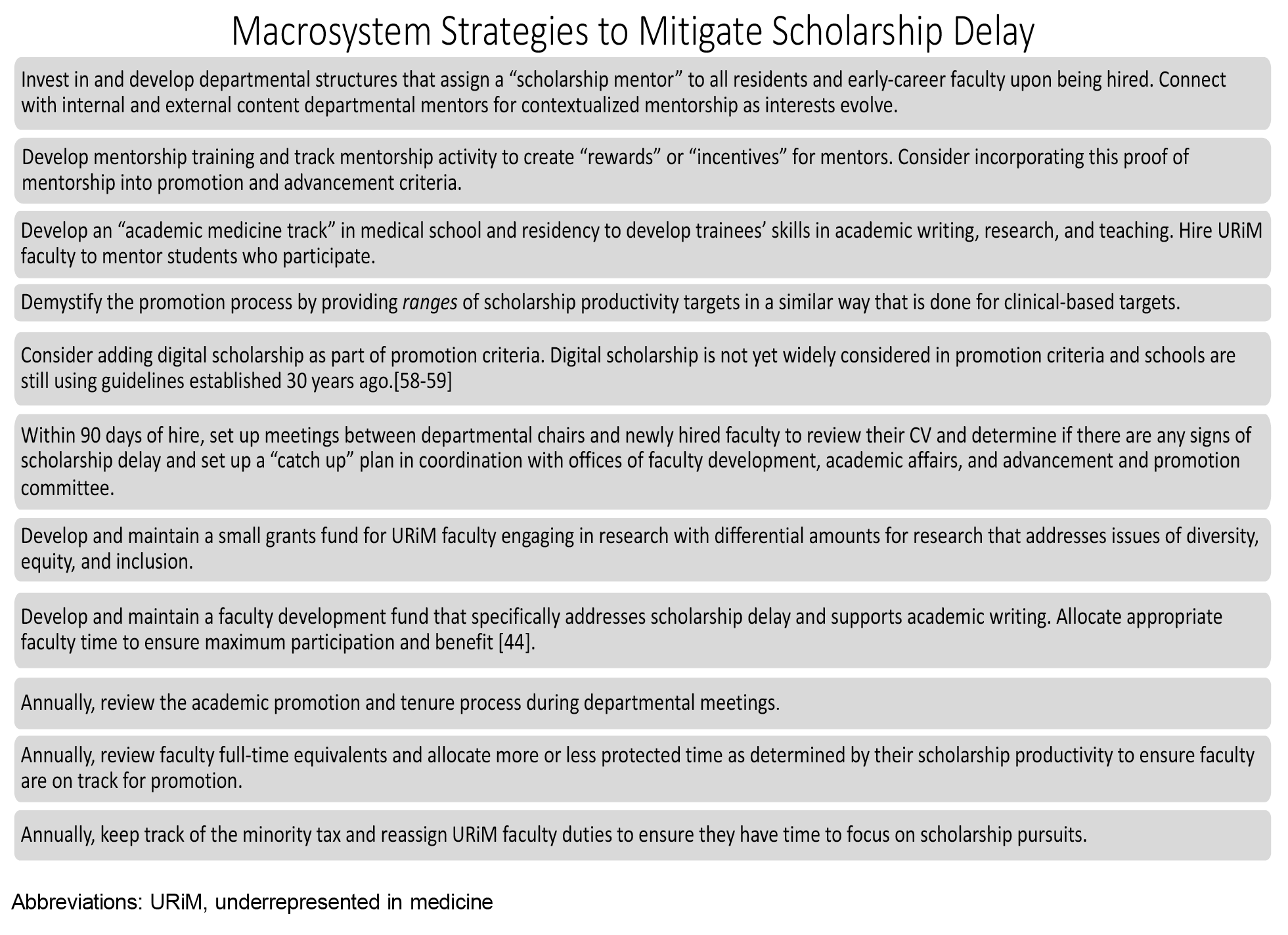

Our review identified several factors that negatively impact the scholarly productivity of early-career URiM faculty in academic medicine. These factors have been previously described as they relate to the minority tax, which refers to the added and inequitable responsibilities that URiM faculty face when tasked with diversity efforts and when dealing with “racism, isolation, mentorship, clinical, and promotion disparities.”20 However, our review of the literature highlights a disparity in scholarship productivity that starts before even reaching faculty rank. This suggests that, for trainees interested in academic medicine careers, addressing scholarship delay is paramount to their success in career advancement. Additionally, it means that departmental chairs can identify newly hired, early career faculty who are starting their careers with scholarship delay. Our review reinforces the urgent need to implement evidence-based solutions to address this problem. We offer microsystem and macrosystem level strategies to consider with suggested timelines in Figure 1, Figure 2, respectively.

Several studies have demonstrated that effective mentorship of early career URiM faculty, including students and residents, helps foster success in their professional careers.9, 38, 45 Mentorship and access to scholarly opportunities, such as early research opportunities in medical school and residency training, are correlated with greater success in a faculty member’s career. Furthermore, the “for URiM by URiM” approach to promote scholarship for junior URiM physicians can be impactful, making the pipeline of mentorship vital as described by Uché Blackstock, a physician and thought leader on bias and racism in health care.46 Establishing relationships with non-URiM mentors is also important. Oh et al described the value of “mentorship networks” and “creative mentoring models” that go beyond the traditional dyad model.47

For those entering faculty roles, Keating et al suggested three tips to ensure academic advancement: (a) timely and thorough documentation of scholarly works and an annual review of the curriculum vitae, (b) effective mentorship with concrete goals and networking opportunities with professionals in advanced roles, and (c) early knowledge of the institutional policies and criteria for promotion.9 Once aware of these expectations, early career faculty must work with their leadership to negotiate new roles and responsibilities and to advocate for protected scholarly time.

The faculty in academic departments with protected time for scholarly work are more likely to be promoted.9 Department leadership should support programs for their early career faculty, especially those with scholarship delay, such as structured writing programs or fellowships. Proulx et al studied the Shut Up and Write program, which improved participants’ publications and grant submissions.48 Kendall Campbell, Judy Washington, and José Rodríguez worked with the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine to develop the Leadership Through Scholarship Fellowship for URiM faculty, which has shown increased productivity and success of their fellows in securing promotion and tenure.49 When academic leaders invest in these faculty development activities, they are aiding the successful promotion of their URiM faculty. Allocating funds and time is imperative. 44, 45

Our literature review found articles that described or addressed scholarship productivity at the URiM student, resident, and faculty levels. However, we did not find articles that tracked scholarship productivity for individuals as they progressed from student to junior faculty. Future studies that map out scholarship productivity in this early career journey, with inclusion of key interventions along the way, can help us better understand what mitigating factors are most effective. Ensuring that we study these interventions in both primary care fields and subspecialties can inform more tailored interventions. To maximize our results, we did not search by individual underrepresented identities; so, we possibly did not capture additional factors that affect specific minority groups.

This study was also limited in its reliance on terms that have variable definitions (eg, early career, scholarship productivity, and academic advancement), which made characterizing the problem of scholarship delay challenging. We need more explicitly defined terms and objective measures of scholarship productivity, with specific parameters for different forms of scholarship. Finally, we conducted a narrative review because available URiM literature was limited. As the literature expands, a future systematic review or scoping review may be possible as well as the ability to characterize scholarship among URiM faculty in tenure and nontenure tracks. More detailed breakdown of faculty data by academic rank, tenure status, and leadership title in the American Board of Family Medicine handbook and the Association of American Medical Colleges faculty reports can help provide additional data for future study. 50, 51

Scholarship delay is a phenomenon that disproportionately impacts early career URiM faculty, and this delay likely starts before they reach faculty rank. Scholarship delay is a novel term, and we recommend its use in future studies to expand the existing literature describing this phenomenon and examining solutions. Mitigating scholarship delay for early career URiM faculty will ensure their meaningful career advancement as well as their enduring contributions to the field of academic medicine.

Conflict Disclosure

Dr Corbin is a Nexplanon trainer for Organon Pharmaceutical Company.

References

-

-

Schimanski LA, Alperin JP. The evaluation of scholarship in academic promotion and tenure processes: past, present, and future.

F1000 Res. 2018;7:1,605.

doi:10.12688/f1000research.16493.1

-

Krzyzaniak SM, Coates WC, Gottlieb M. A guide to creating an educator’s portfolio for the 21st century.

AEM Educ Train. 2024;8(1):e10931.

doi:10.1002/aet2.10931

-

-

Blazey-Martin D, Carr PL, Terrin N, et al. Lower rates of promotion of generalists in academic medicine: a follow-up to the national faculty survey.

J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(7):747-752.

doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3961-2

-

Braxton MM, Infante Linares JL, Tumin D, Campbell KM. Scholarly productivity of faculty in primary care roles related to tenure versus non-tenure tracks.

BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):174.

doi:10.1186/s12909-020-02085-6

-

Jacobs CK, Everard KM, Cronholm PF. Promotion of clinical educators: a critical need in academic family medicine.

Fam Med. 2020;52(9):631-634.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.687091

-

Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists.

J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27.

doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5

-

Keating MK, Pasarica M, Stephens MB, et al. Promotion preparation tips for academic family medicine educators.

Fam Med. 2022;54(5):369-375.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2022.414574

-

Chapman T, Maxfield CM, Iyer RS. Promotion in academic radiology: context and considerations.

Pediatr Radiol. 2023;53(1):8-11.

doi:10.1007/s00247-022-05535-z

-

Rollins LK. Enhancing your scholarship as a family medicine junior faculty member.

Fam Med Community Health. 2020;8(3):e000426.

doi:10.1136/fmch-2020-000426

-

Childs E, Yoloye K, Bhasin RM, Benjamin EJ, Assoumou SA. Retaining faculty from underrepresented groups in academic medicine: results from a needs assessment.

South Med J. 2023;116(2):157-161.

doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001510

-

Kaplan SE, Raj A, Carr PL, Terrin N, Breeze JL, Freund KM. Race/ethnicity and success in academic medicine: findings from a longitudinal multi-institutional study.

Acad Med. 2018;93(4):616-622.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001968

-

Fang D, Moy E, Colburn L, Hurley J. Racial and ethnic disparities in faculty promotion in academic medicine.

JAMA. 2000;284(9):1,085-1,092.

doi:10.1001/jama.284.9.1085

-

Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Mouratidis RW. Where are the rest of us? improving representation of minority faculty in academic medicine.

South Med J. 2014;107(12):739-744.

doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000204

-

Ajayi AA, Rodriguez F, de Jesus Perez V. Prioritizing equity and diversity in academic medicine faculty recruitment and retention.

JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(9):e212426.

doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.2426

-

Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Syed ZA, Shakil A, Schneider FD. Recent trends in faculty promotion in U.S. medical schools: implications for recruitment, retention, and diversity and inclusion.

Acad Med. 2021;96(10):1,441-1,448.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004188

-

Amaechi O, Foster KE, Tumin D, Campbell KM. Addressing the gate blocking of minority faculty.

J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113(5):517-521.

doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2021.04.002

-

Palepu A, Carr PL, Friedman RH, Amos H, Ash AS, Moskowitz MA. Minority faculty and academic rank in medicine.

JAMA. 1998;280(9):767-771.

doi:10.1001/jama.280.9.767

-

Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax?

BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):6.

doi:10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9

-

Campbell KM, Rodríguez JE. Addressing the minority tax: perspectives from two diversity leaders on building minority faculty success in academic medicine.

Acad Med. 2019;94(12):1,854-1,857.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002839

-

Calleson DC, Jordan C, Seifer SD. Community-engaged scholarship: is faculty work in communities a true academic enterprise?

Acad Med. 2005;80(4):317-321.

doi:10.1097/00001888-200504000-00002

-

Murphy M, Callander JK, Dohan D, Grandis JR. Women’s experiences of promotion and tenure in academic medicine and potential implications for gender disparities in career advancement: a qualitative analysis.

JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(9):e2125843.

doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.25843

-

Chang S, Guindani M, Morahan P, Magrane D, Newbill S, Helitzer D. Increasing promotion of women faculty in academic medicine: impact of national career development programs.

J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020;29(6):837-846.

doi:10.1089/jwh.2019.8044

-

-

Burns KH, Borowitz MJ, Carroll KC, et al. The evolution of earned, transparent, and quantifiable faculty salary compensation: the Johns Hopkins pathology experience.

Acad Pathol. 2018;5:2374289518777463.

doi:10.1177/2374289518777463

-

Omoruyi EA, Brown CL, Orr CJ, Montez K. Examining full-time academic general pediatric faculty compensation by gender, race, and ethnicity: 2020–2021.

Acad Pediatr. 2024;24(2):309-317.

doi:10.1016/j.acap.2023.05.017

-

-

Yue T, Khosa F. Academic gender disparity in orthopedic surgery in Canadian universities.

Cureus. 2020;12(3):e7205.

doi:10.7759/cureus.7205

-

Tucker J, Patel S, Benyo S, Wilson MN, Goyal N, McGinn J. Descriptive analysis of otolaryngology program directors with a focus on gender disparity.

Ear Nose Throat J. 2022;1455613221107149.

doi:10.1177/01455613221107149

-

Marhoffer EA, Ein-Alshaeba S, Grimshaw AA, et al. Gender disparity in full professor rank among academic physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Acad Med. 2024;99(7):801-809.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000005695

-

Santiago-Delgado Z, Rojas DP, Campbell KM. Pseudoleadership as a contributor to the URM faculty experience.

J Natl Med Assoc. 2023;115(1):73-76.

doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2022.11.003

-

-

Sun E, Tian J, Eltemsah L, et al. Impact of gender and underrepresented in medicine status on research productivity among ophthalmology residency applicants.

Am J Ophthalmol. 2024;257:1-11.

doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2023.07.018

-

-

Jeffe DB, Yan Y, Andriole DA. Do research activities during college, medical school, and residency mediate racial/ethnic disparities in full-time faculty appointments at U.S. medical schools?

Acad Med. 2012;87(11):1,582-1,593.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826e3297

-

Levine RB, Hebert RS, Wright SM. Resident research and scholarly activity in internal medicine residency training programs.

J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):155-159.

doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40270.x

-

Nguyen M, Chaudhry SI, Asabor E, et al. Variation in research experiences and publications during medical school by sex and race and ethnicity.

JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(10):e2238520.

doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.38520

-

Tella D, Ostad B, Barquin D, et al. Academic productivity among underrepresented minority and women urologists at academic institutions.

Urology. 2023;178:9-16.

doi:10.1016/j.urology.2023.03.044

-

Vaa Stelling BE, Andersen CA, Suarez DA, et al. Fitting in while standing out: professional identity formation, imposter syndrome, and burnout in early-career faculty physicians.

Acad Med. 2023;98(4):514-520.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000005049

-

Russel SM, Carter TM, Wright ST, Hirshfield LE. How do academic medicine pathways differ for underrepresented trainees and physicians? a critical scoping review.

Acad Med. 2023;98(11S):S133-S142.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000005364

-

Tumin D, Brewer KL, Cummings DM, Keene KL, Campbell KM. Estimating clinical research project duration from idea to publication.

J Investig Med. 2022;70(1):108-109.

doi:10.1136/jim-2021-001915

-

Esslinger EN, Van der Westhuizen M, Jalal S, Masud S, Khosa F. Gender-based disparity in academic ranking and research productivity among Canadian anesthesiology faculty.

Cureus. 2020;12(11):e11443.

doi:10.7759/cureus.11443

-

Tucker Edmonds B, Tori AJ, Ribera AK, Allen MR, Dankoski ME, Rucker SY. Diversifying faculty leadership in academic medicine: the program to launch underrepresented in medicine success (PLUS).

Acad Med. 2022;97(10):1,459-1,466.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004611

-

Gutierrez-Wu J, Lawrence C, Jamison S, Wright ST, Steiner MJ, Orr CJ. An evaluation of programs designed to increase representation of diverse faculty at academic medical centers.

J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;114(3):278-289.

doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2022.01.012

-

Blackstock U. Legacy: A Black Physician Reckons With Racism in Medicine. Viking; 2024.

-

Oh L, Linden JA, Zeidan A, et al. Overcoming barriers to promotion for women and underrepresented in medicine faculty in academic emergency medicine.

J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021;2(6):e12552.

doi:10.1002/emp2.12552

-

Proulx CN, Rubio DM, Norman MK, Mayowski CA. Shut Up & Write!

® builds writing self-efficacy and self-regulation in early-career researchers.

J Clin Transl Sci. 2023;7(1):e141.

doi:10.1017/cts.2023.568

-

Robles J, Anim T, Wusu MH, et al. An approach to faculty development for underrepresented minorities in medicine.

South Med J. 2021;114(9):579-582.

doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001290

-

Davis CS, Ha E, Morgan Z, Fagan K, Peterson L, Bazemore A.

The Family Medicine Factbook. American Board of Family Medicine, ABFM Foundation, Center for Professionalism & Value in Health Care; January 2023.

https://familymedicinefactbook.org

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Helton MR, Pathman DE. Scholarship criteria for promotion in the age of diverse faculty roles and digital media.

Fam Med. 2023;55(8):544-546.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2023.554380

-

Johng SY, Mishori R, Korostyshevskiy VR. Social media, digital scholarship, and academic promotion in US medical achools.

Fam Med. 2021;53(3):215-219.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.146684

There are no comments for this article.