Background and Objectives: The Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) antiracism task force created and led an Antiracism Learning Collaborative (ALC) to help STFM members identify racist structures and behaviors within their academic institutions and develop projects to become leaders for change. The Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care was tasked with evaluating whether the 2-year program’s goals were met.

Methods: Through a call for applications, 20 dyads were accepted for participation. At least one dyad member had to be of a racial or an ethnic population that is underrepresented in the medical profession. Participant involvement took place from January 2022 through September 2023. The following data sources were evaluated: project plans, four survey sets, anecdotal meeting notes, mentor meeting forms, and final reports and presentations from the dyads.

Results: A total of 34 participants (17 dyads) completed the study from 17 institutions. Generally, participants learned several antiracism concepts and how to take steps to counter racist structures and behaviors through actionable approaches and language use. Strengths of the program were the tools and resources offered to dyads for their project implementation. Two major challenges were institutional opposition or lack of support and lack of time (both for dyads and for various local community partners).

Conclusions: Overall, ALC met each goal. Future evaluations of similar initiatives should consider defining what success for individual projects looks like and provide a predefined rubric to gauge success.

As the US population and family medicine workforce become increasingly racially and ethnically diverse, 1, 2 academic family medicine has an imperative to implement initiatives that advance racial equity and reduce the prevalence of bias and racism within their institutions. 3, 4 Historically, medical educational institutions often have perpetuated misinformation regarding race and failed to create safe educational environments for trainees, thus contributing to decreased intention of students to work in underserved or minority communities after graduation. 5, 6 In particular, trainees and faculty, especially those racially underrepresented in medicine (URM), have been affected by biased policies and practices within their academic institutions that led to or enabled discrimination. 7-11 Ultimately, these unjust practices and biases have severely negatively impacted URM students’ medical school admission and academic performance, 9 as well as URM faculty and trainees’ grant-funding opportunities. 12

Addressing systemic racism in medicine can resolve or mitigate these negative experiences and have profound positive impacts on both patients and clinicians. For example, research has shown that having a culturally competent 13, 14 and racially and ethnically diverse workforce can lead to better patient and clinician communication, better medical adherence, and higher patient satisfaction. 3, 4 For URM students and trainees, mentorship and allyship are mitigating factors that can increase career and personal satisfaction, provide opportunities for career advancement, and encourage productivity in research. 15, 16 Arguably, the most important factor for enabling sustainable change is buy-in from leadership to support diversity and equity related efforts in academic medical institutions; leaders denote prioritization and set the tone for organizational culture. 17, 18 Thus, medical institutions are central to addressing systemic racism.

For these reasons, the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) appointed an antiracism task force for the purpose of advancing racial equity and reducing the prevalence of racism in academic family medicine. The antiracism task force created an action plan to help operationalize and address concepts such as antiracism, racist structures, and allyship. 19 Existing constructs, 20 combined with STFM’s antiracism and health equity resources, 21 contributed to one of the task force’s creations: the Antiracism Learning Collaborative (ALC). This 2-year collaborative focused on supporting longitudinal projects that helped reduce racism within academic medical institutions. The task force solicited applications through a variety of electronic communications to STFM members and other academic family medicine organizations nationally. Applications consisted of preparticipation surveys, a project work plan proposal, and at least one letter of support from the department chair, dean, or other leader within the participants’ institution. The task force members then reviewed, ranked, and scored 57 applications; in the end, they selected 20 dyads, each with at least one dyad member being URM. The task force members also recruited mentors to provide guidance and expertise to participants; they received 31 applications and settled on 10 mentors, each of which they then paired with two dyads. ALC activities took place from January 2022 through September 2023.

The Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care (RGC), on behalf of the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), evaluated ALC activities to determine whether ALC achieved the five goals described here. RGC was uniquely positioned to evaluate the ALC project because of its extensive work in supporting the primary care pathway for graduate medical education, as well as its work in promoting health equity. Ensuring equitable opportunities and removing barriers for learners are critical to growing the primary care workforce, and thus, central to RGC’s mission.

Goal 1: Empower and Educate Participants so They Will Identify Racist Structures and Behaviors Within Their Academic Institutions and Become Leaders for Change

ALC provided content that emphasized how to recognize racist structures and behaviors embedded in institutions and what actions to take to enable a shift toward antiracist constructs for individuals and organizations. Specifically, topical content included training upstanders, promoting precise use of language, explaining dominant cultural norms, outlining biases and power in institutions, finding allies, maximizing impact, and managing expectations. The ALC task force shared content via presentations, resources, and tools during virtual and in-person meetings and on the STFM Connect platform. Additionally, participants completed an online course on leading change (www.stfm.org/leadingchange). Discussions focused on experiences and learnings of task force members, presenters, mentors, and participants; these were shared throughout the ALC program.

Goal 2: Promote Allyship

ALC promoted allyship in numerous ways. First, ALC required all dyads to include one URM and one ally. Teams also were required to develop SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound) objectives and describe how these objectives promoted allyship. Individual project objectives varied from generalized descriptions to specific aspects of allyship promotion and enhancement. Lastly, presentations and discussions focused on or referred to the importance of allyship in partnerships and collaborations.

Goal 3: Spread Effective Change Strategies

To help participants disseminate their project findings and affect sustainable, effective change at their institutions, ALC provided a loose framework based on five key components.

-

Know institutional history, understand previous work in local environments, and build on existing initiatives.

-

Cultivate, sustain, and enhance relationships.

-

Utilize external institutions to foster local community engagement.

-

Encourage and provide participants with different opportunities to disseminate their project findings via channels such as presentations, teaching seminars, and publications.

-

Encourage participants to be pragmatic in their approach, align their project objectives with their institutions’ missions, and incorporate sustainability plans.

Goal 4: Identify Which Projects/Strategies/Dyad Combinations Were Effective (and Why), With Strategies for Spreading Them to Other Institutions

Through the cultivation and dissemination of information and resources, ALC encouraged participants to develop sustainable strategies that could be applied at other institutions. ALC stressed the importance of engagement with their stakeholders, whether they were community partners, leadership, or those affected by interventions (ie, students, residents, and/or faculty). ALC also noted the importance of being selective and intentional about who to work with and the need to secure time investments from leadership stakeholders up front.

Goal 5: Identify Which Components of ALC Were Effective and Which Should Be Changed for Future Cohorts

ALC included five overarching components that provided the foundation for the project: infrastructure, dyads, project plans, mentorship, and meetings. ALC infrastructure was flexible so that it could respond to unforeseen needs. A dedicated STFM staffer served in a management and administrative capacity, which was critical to program implementation. As for mentorship, the task force tried to pair dyads with mentors based on availability, geography, and skill set. ALC held both virtually and in-person meetings.

The project evaluation used multiple data sources: project plans; four survey sets (baseline, 7-month, 14-month, and 1-month post program) that contained both quantitative and qualitative assessment questions; four anecdotal meeting notes (in-person and virtual); five mentor-mentee meeting form sets; and 17 final reports and presentations from the dyads. RGC performed quantitative and qualitative analyses, and an STFM staff member, an outside consultant specialized in antiracism, and an ALC task force member reviewed results. For the quantitative analysis, we included only those individuals who participated in all four survey sets. The study received AAFP Institutional Review Board approval. Table 1 provides a breakdown of how the measures under each goal were analyzed qualitatively and quantitatively.

|

Goal 1: Empower and educate participants

|

|

Measures

|

Qualitative

|

Quantitative

|

|

Improvement in self-reported confidence in racism reduction (pre vs post)

|

• Personal attributes/barriers described

|

• Confidence scores over time (pre, base, mid, and post)

|

|

Perception of racism within participants’ institutions (pre vs post)

|

• Institutional successes/barriers described

|

• Perception scores (six questions) over time (pre, base, mid, and post)

|

|

Level of impact of projects on reducing structural racism (post)

|

• Learnings to be shared

• Implementation components

• Written project plans and verbal reports

|

• Institutional rating over time (pre, base, mid, and post)—two-way contingency table

• Progress rating (post)

|

|

Types of changes/projects that had the highest level of impact

|

• Implementation components

• Sustainability

• Written project plans and verbal reports

• Next steps to complete project

|

• Mentor support (post)

|

|

Goal 2: Promote allyship

|

|

Measures

|

Qualitative

|

Quantitative

|

|

Level of impact of allyship (post)

|

• Mentor descriptions (forms)

• Written project plans and verbal reports

|

• One of the goals of this learning collaborative was to promote allyship. Do you think that goal was accomplished? (post only)

|

|

Goal 3: Spread effective change strategies

|

|

Measures

|

Qualitative

|

Quantitative

|

|

Types of changes/projects that had the highest level of impact

|

• Implementation components

• Sustainability

• Written project plans and verbal reports

• Next steps to complete project

|

• N/A

|

|

Goal 4: Identify effective projects/strategies/dyad combinations

|

|

Measures

|

Qualitative

|

Quantitative

|

|

Level of impact of projects on reducing structural racism (post)

|

• Implementation components

• Learnings to be shared

• Written project plans and verbal reports

|

• Institutional rating over time (pre, base, mid, and post)—two-way contingency table

• Progress rating (post)

|

|

Types of changes/projects that had the highest level of impact

|

• Implementation components

• Sustainability

• Written project plans and verbal reports

• Next steps to complete project

|

• N/A

|

|

Goal 5: Identify effective components of the Antiracism Learning Collaborative

|

|

Measures

|

Qualitative

|

Quantitative

|

|

Mentor perceptions (post)

|

• Mentor descriptions (forms)

|

• Mentor support (post)

|

|

Types of changes/projects that had the highest level of impact

|

• Implementation components

• Sustainability

• Written project plans and verbal reports

• Next steps to complete project

|

• N/A

|

Qualitative Analytic Plan

The qualitative data sources consisted of all the aforementioned data sources that included open-ended responses. A member from the research team summarized the data for each dyad and then extrapolated conclusions based on the findings. These findings were shared with the larger research team to ensure alignment with the quantitative data. The team also discussed the significance and meaning of the data. Emergent themes related to each of the five evaluation goals were extracted from the findings and discussions with the team. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus with the research team at-large.

Quantitative Analytic Plan

The quantitative data source consisted solely of the survey sets, excluding the open-ended responses. Summary statistics on personal demographics and institutional characteristics were derived from the baseline survey. Outcome variables included confidence, six antiracism perceptions, institutional rating, progress, perception of mentor support, and barriers, attributes, and support. Institutional rating, progress, and mentor perception outcome measures were analyzed via a stacked bar chart and two-way contingency table. The mentor perception outcome measures were analyzed via a group mean rating chart. The remaining outcome measure—barriers, attributes, and support—was analyzed via stacked bar charts.

Participant Characteristics

At the conclusion of ALC, 20 dyad spots were filled and 17 of 20 dyads (total of 34 participants) completed the program. For the purposes of the quantitative analysis, only those who participated in all surveys were included, which resulted in a total of 31 participants analyzed (Table 2). Most participants were from the West (35.48%), had an MD (77.42%), were Black or African American (41.94%), and/or were from a community-based, university residency program (35.48%).

|

Variable (by participant, not dyad)

|

Categories

|

Participants, n (%)

|

|

Region

|

Midwest

|

8 (25.81)

|

|

Northeast

|

5 (16.13)

|

|

Northwest

|

0

|

|

Not in US

|

1 (3.23)

|

|

Southeast

|

4 (12.90)

|

|

Southwest

|

2 (6.45)

|

|

West

|

11 (35.48)

|

|

Degree of education

|

DO

|

2 (6.45)

|

|

MD

|

24 (77.42)

|

|

MEd

|

1 (3.23)

|

|

PhD

|

4 (12.9)

|

|

Race/ethnicity

|

Asian or Asian American

|

5 (16.13)

|

|

Black or African American

|

13 (41.94)

|

|

White or Caucasian

|

9 (29.03)

|

|

Hispanic or Latino

|

4 (12.90)

|

|

Institution

|

Community-based, nonaffiliated residency program

|

2 (6.45)

|

|

Community-based, university residency program

|

11 (35.48)

|

|

Private medical school

|

1 (3.23)

|

|

Public medical school

|

10 (32.26)

|

|

University-based residency program

|

7 (22.58)

|

Goal 1

At each survey stage, participants were asked about confidence, that is, “How confident are you in your skills to lead meaningful change within your institution?” The mean confidence rating declined at the 7-month survey, then increased for the remaining surveys. By the conclusion of ALC, 38% of participants noted increased confidence in their skills to lead meaningful change in their institution, and 100% of participants believed they incorporated strategies that led to positive outcomes when implementing their projects. See Table 3 for exemplar quotes associated with each goal.

|

Goal

|

Example comments

|

|

Goal 1: Empower and educate participants so they will identify racist structures and behaviors within their academic institutions and become leaders for change

|

“As a new faculty member trying to find my way and work on issues I’m passionate about, the collaborative helped to improve my confidence, keep me on track (with specific deadlines/goals), and helped me to give my work respect within my institution.”

|

|

“[Of the guest speakers invited to talk with ALC participants,] Dr Sunny Nakae’s talk in Kansas City was revelatory; I learned a lot and think about the talk often. She offered empathy and real useful advice. Next, [STFM task force leader] Dr Trisha Elliot’s presence generally was inspiring and she served as an excellent role model. The panel at the final session was very helpful for career advice.”

|

|

Goal 2: Promote allyship

|

“Diverse resident leaders have held us accountable to this work; working with an amazing ally leader has been instrumental to this work. It was timely and we were able to recognize that we had to pivot, and did so accordingly.”

|

|

“It is helpful to have leaders of different social identities lead this work, to provide a rich diverse perspective to help this work go further. Furthermore, it was helpful to have both a URM/BIPOC leader and a White ally leader help work on this from their own vantage points and use their individual and collective lived experience to go deeper.”

|

|

Goal 3: Spread effective change strategies

|

“Providing faculty with a directive one-pager to review course materials for appropriate use of race equips them with a tool to take action rather than just passively receiving professional development.”

|

|

“There are materials out there, so don’t reinvent the wheel. Listen to those around you who have experience in DEI work and/or lived experience in the realm of racial inequity (interprofessionals and patients/communities) and actively follow their lead regarding problems to address and how.”

|

|

Goal 4: Identify which projects/strategies/dyad combinations were effective (and why), with strategies for spreading them to other institutions

|

“Alignment with institutional mission/vision is critical to success. Also, communicate the alignment of objectives/outcomes of desired change to key stakeholders in a way that will resonate and amplify the opportunity.”

|

|

“Pivot earlier and look for low-hanging fruit. For example, although our project wanted to have face-to-face sessions, we [should] have easily implemented virtual as a phase one approach [instead] leading to sooner impact.”

|

|

“Involving students or other learners has been really helpful for a number of reasons. First of all, they are the key stakeholders; the curriculum serves them and so their input matters. Secondly, bringing student data back to faculty/leadership was an effective strategy to catalyze change/acceptance. Third, it disperses workload and empowers leaders to engage with the work.”

|

|

Goal 5: Identify which components of the learning collaborative were effective and which should be changed for future cohorts

|

“The STFM Antiracism Learning Collaborative was an amazing experience. I especially enjoyed hearing of best practices and lived experiences of the guest speakers. This was extremely helpful in norming the strengths and challenges of working in the antiracism space. It would be great to include more voices.”

|

|

“I really enjoyed the in-person experiences; it really helped us deepen our connection and do critical learning and unlearning related to antiracism. I think there should be monthly virtual experiences to help sustain our community and connection over the duration of the collaborative.”

|

|

“The ‘official’ support from the STFM enabled leadership buy-in. The genuine engagement of the people (task force leader, STFM staff and project leaders, dyads, mentors) was so important. Rules for formation of dyad worked well in my opinion, with effective diversity of lived experience related to antiracism work in medical education within the participants. I’m not sure if it was purposeful, but the other very effective aspect was the diversity in stage of career from residents to those who are eligible for retirement; meeting with other STFM members living their purpose is always refreshing, and this group was exceptionally uplifting.”

|

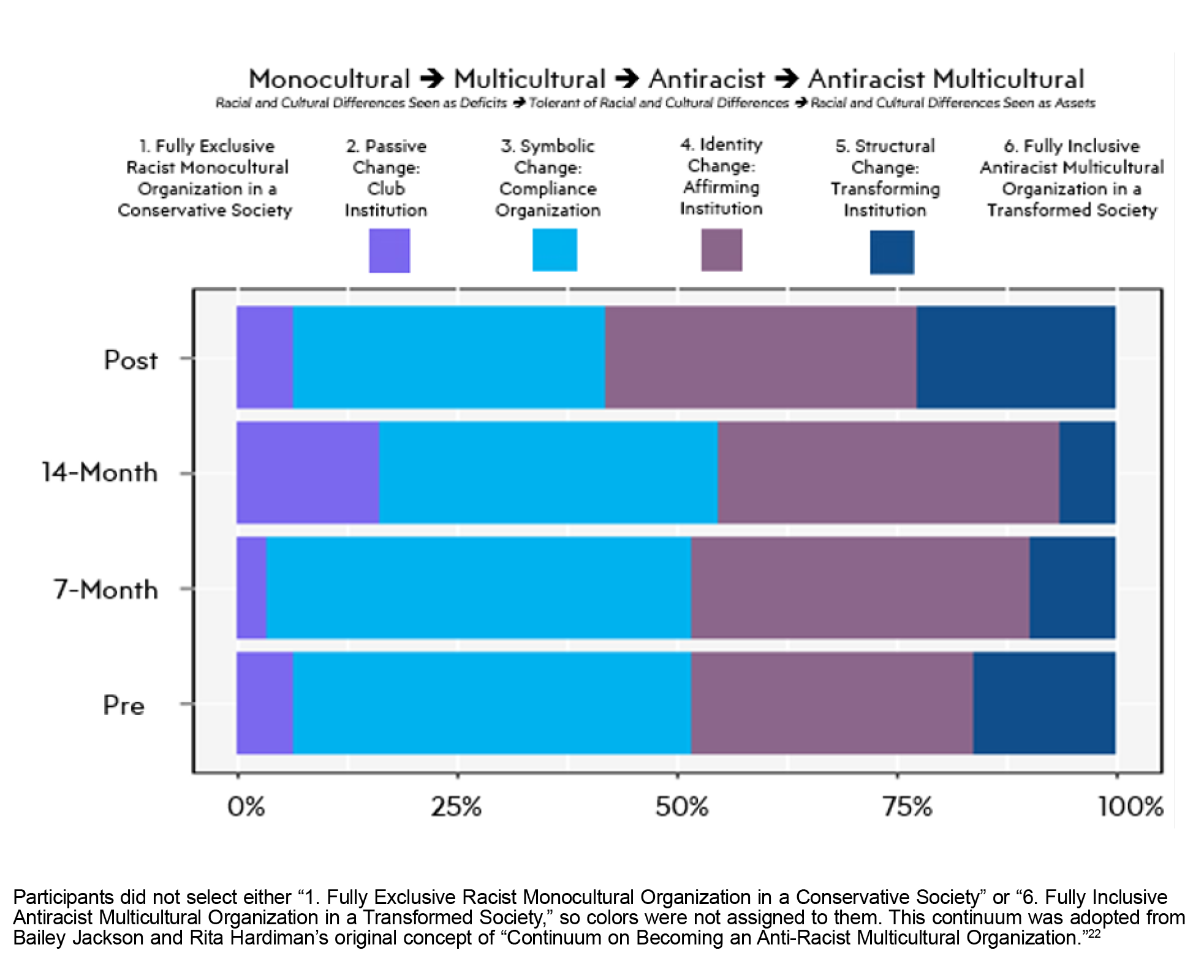

Participants also were asked to “Review the Continuum on Becoming an Anti-Racist Multicultural Organization. 22 Based on the descriptions, where would you rate your institution?” Responses fluctuated over time, as seen in Figure 1. At the 14-month survey, the passive change category (club institution) increased substantially, and the structural change category (transforming institution) decreased, meaning that more participants rated their institutions lower on the continuum, that is, monocultural, compared to the baseline and 7-month surveys. In the post survey, participants rated more institutions in the structural change category (transforming institution) than the 14-month survey.

Goal 2

Two projects listed allyship as the central focus for antiracism promotion and institutional change; a handful of others focused on informing and guiding education for allies or specifically referred to getting buy-in from allies for successful project implementation; and the remaining ones recognized the importance of allyship for project implementation. By the conclusion of ALC, 94% of participants said that ALC met its goal to promote allyship.

Goal 3

Participants indicated that understanding institutional history was beneficial in gaining buy-in from leadership. Participants who developed mutually beneficial relationships and discussed managing expectations in their institution reported more buy-in and facilitated change. Additionally, participants saw value in exploring potential connections outside of their department because others may have been working on similar initiatives. Participants who engaged local community partners in their projects thought that initiating and/or extending relationships to drive action were well worth their efforts. Participants indicated that following a practical and critically thought-out plan made using their data to tell a compelling story easier, as well as to garner institutional support.

Goal 4

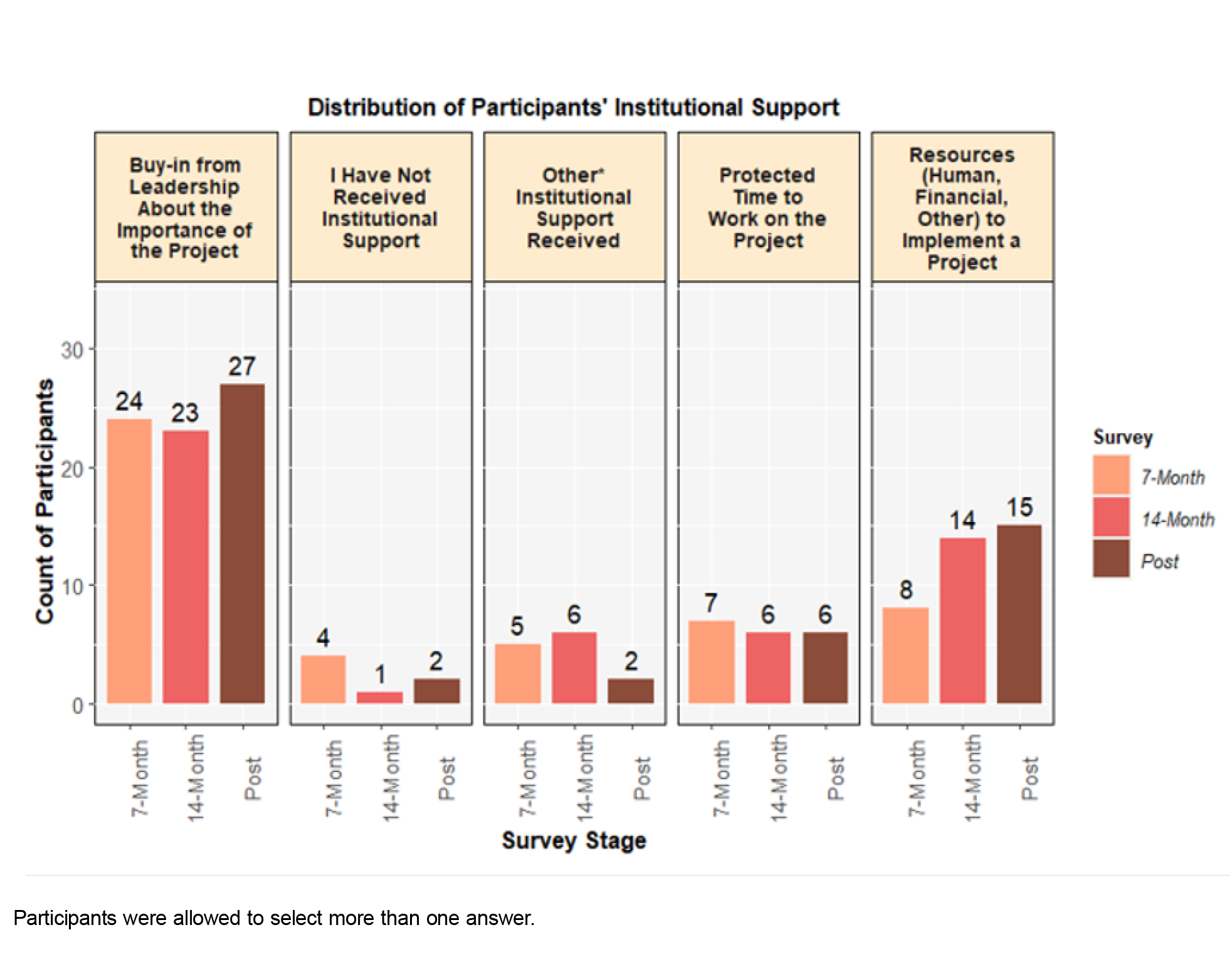

The most reoccurring and effective strategy the participants acclaimed centered on engagement with stakeholders. Buy-in from institutional leadership was particularly important to participants, as noted in the survey question, “Which of the following institutional supports can you credit with any success you’ve had implementing your project?” (Figure 2). To secure chances of buy-in, participants claimed demonstrating value to their institutions as a critical strategy to employ.

Key indicators that led to effective projects included incorporating existing resources and tools and integrating sustainability into project planning. Utilizing existing resources and tools, whether from ALC or elsewhere, saved time and effort. Similarly, incorporating antiracist language and concepts, such as changing language from determinants to drivers and integrating structural racism into previous concepts, into existing curricula were appealing to leadership due to the streamlined approach and structure, which increased the chances of a sustainable project. Obtaining funding to support current and future efforts also laid the groundwork for future success.

Several topics emerged that contributed to effective dyad relationships: logistics, soft skills, and ability to pivot. Prioritizing and organizing their projects helped dyads meet deadlines and maintain a sense of accountability. To overcome barriers and delays to project plans, dyads had to use soft skills, such as creative thinking and patience. Lastly, their ability to pivot in difficult situations was critical in moving their projects forward.

Goal 5

Regarding working in a dyad, participants overwhelmingly praised the structure because it allowed them to pair with another at a different career stage and lived experience. However, some dyads expressed challenges with consistently meeting with their partner due to external commitments. Most found meetings with their mentors to be beneficial, because the meetings helped clarify next steps and provided an opportunity for mentees to share their needs, frustrations, and experiences. Overall, a direct, positive, association emerged between the number of times participants met with their mentors and program progression. Overall, attendees found the in-person meetings to be more beneficial and effective for engaging with other participants. However, virtual meetings were still helpful in that they provided an opportunity for leadership to check in with participants and for participants to touch base with their fellow participants. When participants expressed a desire for more meetings to sustain ALC connectivity and discuss successes and challenges, ALC responded by implementing virtual office hours and unstructured time to talk; however participation in both was extremely limited, and these were discontinued.

Summary

Our evaluation focused on whether ALC met the five goals it set out to achieve; overall, ALC met each goal, however the degree of effectiveness of each achievement is open to interpretation because the data were subjective. Generally, participants learned antiracism concepts and how to counter racist structures and behaviors, such as identifying dominant cultural norms or tactics used to suppress others within institutions, implementing actionable approaches (ie, being an agent of change), and using antiracist language. Strengths of the learning collaborative were the tools and resources offered to the dyads for individual project implementation, such as the discussion platform and the leading change course.

Over the duration of ALC, participants encountered both expected and unexpected challenges; and depending on the strength of their influence over a given challenge, they either were able to adapt and complete their projects or were forced to pivot their project plans entirely. For example, when participants encountered “anti-antiracism/anti-diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI)” legislative mandates enacted in some states, as well as various levels of pushback from their institutions, dyads had to completely alter their projects to comply with state law and/or discuss the intentions of their projects with institutional stakeholders, which may have inspired future change in those institutions. Participants also faced challenges regarding the lack of protected time to implement their projects, even though prior to being selected for participation, applicants were required to obtain a letter of support from their department chair, dean, or other leader indicating how they and the department, program, or institution would support the dyad member and their change efforts.

ALC Program and Evaluation Limitations

Several program and evaluation limitations existed. First, a small number of institutions and dyads participated in the project, yielding limited data. Increasing the sample size would help with generalizability. Second, each institution had its own viewpoint on the importance of implementing antiracist projects, so participating dyads received varying levels of institutional support. For the evaluation team, demarcating specific cutoffs regarding what constituted goal achievement was difficult due to different starting and ending points. In future projects, the project leadership and evaluation team should define overall metrics for success and develop a rubric participants can use to gauge their individual project’s success. Third, the overall project evaluation was based primarily on self-reported data. These data are prone to biases, such as limited flexibility in responses, misinterpreted questions, and self-serving responses. Hence, developing an overall metrics of success and a defined rubric can help mitigate this issue.

Future Directions

To best serve participants and institutions in their journeys to reduce racist structures and behaviors, enhancements to future collaboratives could maximize the return on effort and investment. Considerations for future endeavors include potentially conducting a longitudinal study of institutional outcomes to see whether changes continue or project implementation is sustainable; encouraging participants to seek funding to support their projects (eg, through implementation and data analysis) and providing ideas for funding sources; providing more opportunities for in-person collaboration, communication, and structured networking between dyads; and providing suggestions to mentors on how to engage with their mentees in a more structured path that detailed what to do and how to move forward.

Our evaluation of STFM’s ALC pilot program concludes that the project was overall successful. ALC provided subject matter experts, tools, resources, mentors, and structural support (eg, funding for travel to meetings) that enabled participants to use their expanding knowledge and skills to take actionable steps to identify and mitigate racist structures and behaviors within their institutions. Participants were supportive and appreciative of the opportunity to be part of the collaborative, and lessons learned during the implementation and evaluation process can be used to shape ongoing ALC efforts to reduce racism in family medicine education.

Presentations

Preliminary findings were presented in-person via a poster at the 2023 North American Primary Care Research Group Annual Meeting, October 30 to November 3, in San Francisco, California. Final results were presented at the 2024 Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference, May 4 to 8, in Washington, DC.

Conflict Disclosure

This study was partially financially supported by the Adtalem Global Education Foundation.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the members of the STFM Antiracism Initiative Task Force: Tricia Elliott, MD; Thomas W. Bishop, PsyD, MA; Echo Buffalo-Ellison, MD; Renee Crichlow, MD; Edgar Figueroa, MD; Victoria Gorski, MD; Cleveland Piggott, Jr, MD, MPH; Kristin Reavis, MD; Mary Theobald, MBA; Emily Walters; and Julia Wang, MD.

References

-

-

-

-

Walters E. Building a diverse academic family medicine workforce: URM initiative focuses on four strategic areas.

Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(1):87-88.

doi:10.1370/afm.2511

-

Lehn C, Huang H, Hansen-Guzman A, et al. Longitudinal antiracism training for family medicine residency faculty.

PRiMER. 2023;7:40.

doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2023.351932

-

Phelan SM, Burke SE, Cunningham BA, et al. The effects of racism in medical education on students’ decisions to practice in underserved or minority communities.

Acad Med. 2019;94(8):1,178-1,189.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002719

-

Espaillat A, Panna DK, Goede DL, Gurka MJ, Novak MA, Zaidi Z. An exploratory study on microaggressions in medical school: what are they and why should we care?

Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8(3):143-151.

doi:10.1007/S40037-019-0516-3

-

Orom H, Semalulu T, Underwood W III. The social and learning environments experienced by underrepresented minority medical students: a narrative review.

Acad Med. 2013;88(11):1,765-1,777.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a7a3af

-

Odom KL, Roberts LM, Johnson RL, Cooper LA. Exploring obstacles to and opportunities for professional success among ethnic minority medical students.

Acad Med. 2007;82(2):146-153.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31802d8f2c

-

Hung R, McClendon J, Henderson A, Evans Y, Colquitt R, Saha S. Student perspectives on diversity and the cultural climate at a U.S. medical school.

Acad Med. 2007;82(2):184-192.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31802d936a

-

Dickins K, Levinson D, Smith SG, Humphrey HJ. The minority student voice at one medical school: lessons for all?

Acad Med. 2013;88(1):73-79.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182769513

-

Evans MK, Rosenbaum L, Malina D, Morrissey S, Rubin EJ. Diagnosing and treating systemic racism.

N Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):274-276.

doi:10.1056/NEJMe2021693

-

White J, Plompen T, Tao L, Micallef E, Haines T. What is needed in culturally competent healthcare systems? a qualitative exploration of culturally diverse patients and professional interpreters in an Australian healthcare setting.

BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1,096.

doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7378-9

-

Brach C, Fraser I. Reducing disparities through culturally competent health care: an analysis of the business case.

Qual Manag Health Care. 2002;10(4):15-28.

doi:10.1097/00019514-200210040-00005

-

Bonifacino E, Ufomata EO, Farkas AH, Turner R, Corbelli JA. Mentorship of underrepresented physicians and trainees in academic medicine: a systematic review.

J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(4):1,023-1,034.

doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06478-7

-

Bath EP, Brown K, Harris C, et al. For us by us: instituting mentorship models that credit minoritized medical faculty expertise and lived experience.

Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:966193.

doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.966193

-

Eze N. Driving health equity through diversity in health care leadership.

NEJM Catalyst. 2020;1(5).

doi:10.1056/CAT.20.0521

-

-

-

-

-

There are no comments for this article.