Background and Objectives: The number of US family physicians providing pregnancy care continues to decline. The 2023 US family medicine training requirements increased flexibility for pregnancy care training. We aimed to evaluate the correlation between residency program structures and curriculum with graduate maternity care provision.

Methods: Our prospective cohort study of family medicine graduates used the 2018 Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) program director survey to measure program characteristics and maternity care curricular elements and the 2021 family medicine national graduate survey (NGS) of 2018 residency graduates to measure outcomes. Logistic regression determined the associations between residency elements and graduate provision of maternity care and deliveries.

Results: The cohort included 779 graduates (48% of the NGS sample). A total of 28.5% reported providing maternity care (MC) and 13.2% reported performing deliveries. In adjusted models, performing more than 80 deliveries during residency (MC OR=4.70 [3.21, 6.88]; Deliveries OR=15.39 [8.21, 28.85]) and exposure to six or more faculty providing this care (MC OR=2.37 [1.62, 3.47]; Deliveries OR=4.75 [2.58, 8.72]) were associated with providing maternity care and deliveries in practice. Four or more months of obstetrics training was associated with performing deliveries only (OR=3.34, [1.98, 5.61]). Neither program characteristics nor a continuity delivery requirement was associated with providing maternity care or deliveries.

Conclusions: In a large national cohort study, performing more than 80 deliveries during residency, exposure to six or more faculty delivering babies, and completing four or more months of obstetrics training (deliveries only) were associated with graduates providing maternity care and deliveries. These findings align with the 2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Family Medicine Residency Requirements for comprehensive pregnancy care training.

The percentage of family physicians who provide pregnancy care has been steadily decreasing.1–5 This trend persists despite an unmet need for and maldistribution of pregnancy care services, especially in rural communities, and persistently high US maternal mortality rates.6–8 Interest in and intention to provide pregnancy care among US family medicine residency graduates greatly exceeds the number who ultimately do so.9,10 Pregnancy care training is required for all family medicine residencies; however, the focus and scope of these experiences vary widely from one program to another.11,12 Previous studies have identified geographic region, employment opportunities, lifestyle considerations, and malpractice concerns as factors influencing decisions about providing pregnancy care in practice.10,13–18 Other studies focusing on the impact of pregnancy care training during residency were informative but had limitations. Most explored factors associated with the intent to provide pregnancy care rather than exploring actual practice patterns and relied on estimated rather than actual graduate outcomes.12,17 Many focused on minimum training requirements rather than the impact of robust training.19 The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) pregnancy care requirements for family medicine residency were revised in 2023 to allow programs more flexibility and to include specific training requirements for the practice of comprehensive maternity care, including managing deliveries, after graduation. Pregnancy care practice by graduates whose training was consistent with the 2023 comprehensive pregnancy care requirements has not been explored.

Comprehensiveness in family medicine practice has been associated with decreased hospitalizations and decreased health care costs.20 Increasing the number of family medicine residency graduates who provide pregnancy care has been suggested as a strategy for maintaining family medicine comprehensiveness; for improving access to care, especially in rural and underserved communities; and for reducing health care disparities for pregnant people and children.10,19–24 Understanding residency-related factors that correlate with future pregnancy care practice will support curricular design and development of training structures that enable graduates to achieve the competencies needed to pursue this path.25 To this end, this study investigates the demographic characteristics, residency structures, and curricular elements associated with family medicine graduates providing pregnancy care in practice. Note that while we preferentially refer to “pregnancy care” out of respect for the diversity of persons who may be pregnant, we refer to “maternity care” when discussing this study because this term was used in the study surveys and was commonly used at that time, prior to widespread recognition of the need for greater sensitivity in describing the care of pregnant people. For the purpose of this study, “maternity care” describes any care provided specifically for pregnancy in any setting.

Setting and Participants

The Family Medicine Residency Outcomes Project (FM-ROP) is a prospective cohort study of 2018 family medicine residency graduates that explored training factors associated with outcomes of interest; the project’s goal was to identify key residency structures and processes that achieved desired practice outcomes. The FM-ROP study design and methods are described in detail elsewhere.25 Briefly, data about residency curricula that these graduates experienced were obtained from a Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) program director survey26,27 that was administered in the summer of 2018.28 The survey asked program directors to provide their program’s ACGME identification number and answer questions about their program over the previous 3 years (the time interval when the 2018 graduates completed residency). The CERA survey questions and de-identified results are available on the CERA website.29 These data were linked to graduate practice outcome data from the 2021 American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) national graduate survey (NGS).30–32 The 2021 NGS questions and aggregate results are available on the ABFM website.3 Resident demographics were gathered from ABFM administrative databases. Race was self-reported by the resident during registration for the 2018 ABFM initial certification examination in response to a “select best” question and is reported here as is, except that “Native American/Alaska Native” and “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander” were combined into an “Indigenous” category due to the small sample size.

Our primary study focus was to determine whether graduates were providing maternity care and performing deliveries in practice 3 years after completing residency. The exposures of interest were measured with the CERA survey and included various program structures and curricular processes. Residency program structures included region of program, type of community served by program (urban, urban/suburban, rural), size of program, program type (university, community-university affiliated, community-unaffiliated, military), program accreditation type, and presence of other training programs (specifically obstetrics). Residency program curricular processes included the number of faculty providing maternity care and performing deliveries, the months of required obstetrics training, the presence of a continuity delivery requirement, the presence of group prenatal care, and the presence of a family medicine obstetrics (FM-OB) fellowship or track. The number of deliveries a graduate performed in residency was measured at the graduate level with the NGS. Graduate demographics (age, gender, degree type, whether graduated from an international medical school, race/ethnicity) were obtained from ABFM administrative databases. Practice information collected with the NGS included practice region and countylevel practice rurality using the Rural-Urban Continuum Codes.33 For the CERA variables concerning the number of faculty practicing maternity care or performing deliveries, the number of months of obstetrics training, and resident delivery volume, the natural distribution of responses as the primary considerations for choosing the cut-points for a binomial variable. We also considered the 2023 ACGME family medicine requirements for comprehensive maternity care practice, because we wished to explore how our findings related to these requirements.

Data Analysis

The ABFM research staff merged the program director responses in the 2018 CERA survey with the residency graduate responses on the NGS according to the ACGME program identification number. The unit of analysis was the residency graduate. The final FM-ROP dataset contained all respondents to the NGS whose program director responded to the CERA survey.

First, we used descriptive statistics to characterize our sample. Then we conducted bivariate analyses, which were performed with a false discovery rate post hoc test to determine baseline significance. We conducted two separate multiple logistic regressions to determine independent associations between graduate characteristics and residency curricula and structure with our main outcomes—practicing maternity care and performing deliveries. We used SAS v9.4 software for all analysis.34 The overall project was approved by the American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board.

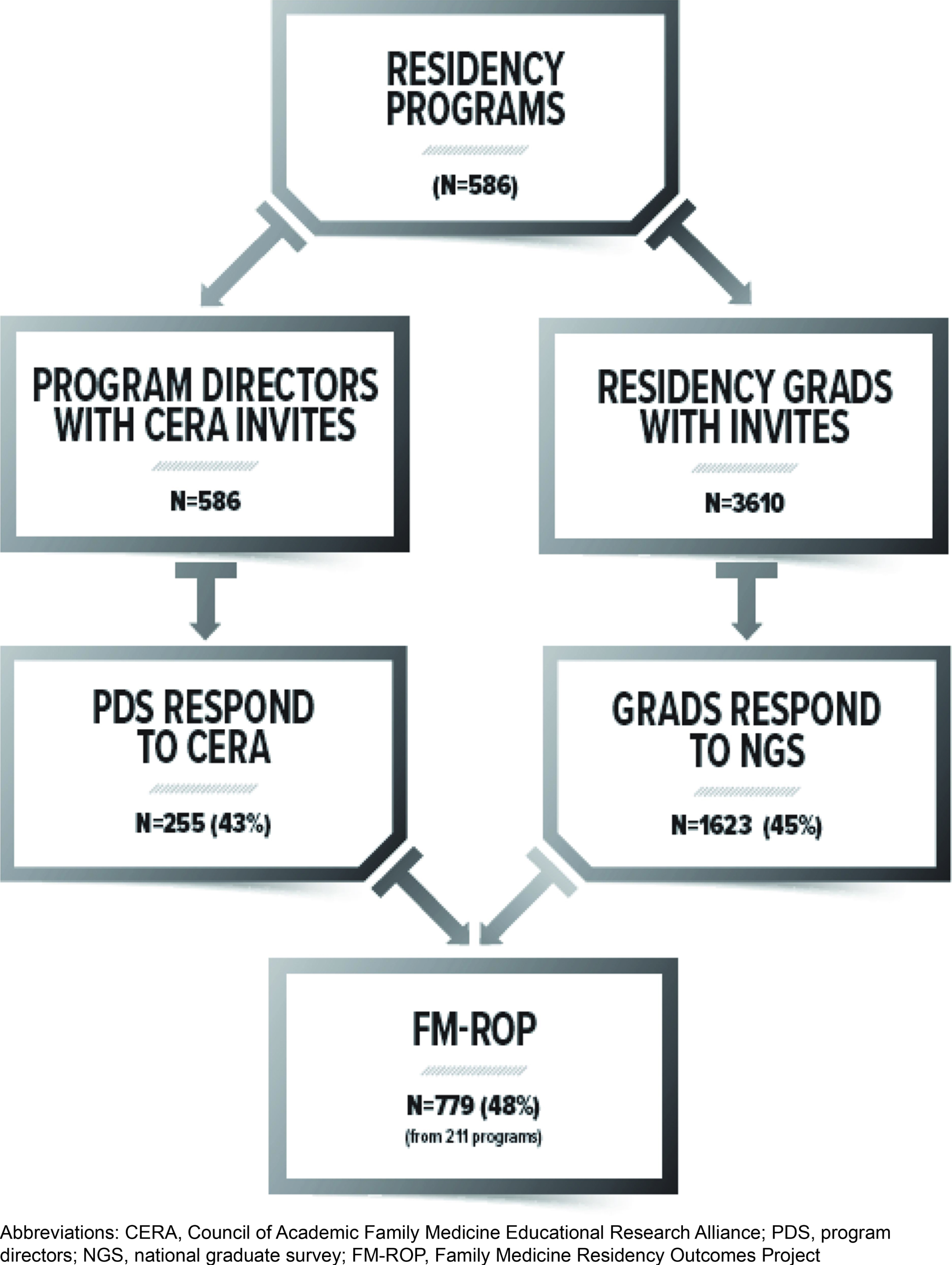

The response rate for the 2018 CERA survey was 43.7% (255/586). The response rate for the 2021 NGS was 45.0% (1,623/3,610). After merging the two data sets, we lost 44 programs because no residents responded to the NGS and 844 residents because their program director did not respond to the CERA survey. Our final analytic sample included 779 graduates from 211 residencies (Figure 1).

For our final analytic cohort, 28.5% (214/752) reported providing maternity care, and 13.2% (99/752) reported performing deliveries (Table 1). Graduate characteristics that were positively associated with providing maternity care and performing deliveries consisted of being a US medical school graduate, being racially White, practicing in a rural area, and practicing in the Midwest or West. Program characteristics that were positively associated with providing maternity care and performing deliveries included program region and size. Most graduates providing maternity care and performing deliveries completed residency in the Midwest or West and were least likely to have trained in the Northeast. Regarding program size, 87.0% of graduates providing maternity care and 90.7% of graduates performing deliveries trained in programs with 19 or more residents. The presence of an OB/GYN residency at the sponsoring institution was negatively associated with only performing deliveries (Table 1). Program curricular processes that were positively associated with graduates providing maternity care and performing deliveries consisted of at least six faculty members performing or supervising deliveries, at least four required curricular months of obstetrics training, performance of at least 80 deliveries during residency, and the presence of an FM-OB track or fellowship (Table 2). The presence of group prenatal visits was associated with performing deliveries only. However, a continuity delivery requirement was not significant.

|

|

Total

|

Practicing maternity care

|

Maternity care

|

Performing deliveries

|

Delivery

|

|

N=752 n (%)

|

N=214 n (%)

|

P values

|

N=99 n (%)

|

P values

|

|

Graduate demographics

|

|

Age (mean, SD)

|

34.8 (3.9)

|

34.63 (2.95)

|

.1823

|

34.38 (2.97)

|

.1070

|

|

Gender (female)

|

429 (57.0)

|

135 (63.1)

|

.0559

|

65 (65.7)

|

.0903

|

|

Degree (MD)

|

594 (79.0)

|

176 (82.2)

|

.1796

|

84 (84.8)

|

.1474

|

|

IMG

|

194 (25.8)

|

43 (20.1)

|

.0487a

|

8 (8.1)

|

.0003a

|

|

Race

|

.0487a

|

|

.0012a

|

|

White

|

488 (66.5)

|

147 (70.3)

|

|

84 (85.7)

|

|

|

Black

|

65 (8.9)

|

12 (5.7)

|

|

3 (3.1)

|

|

|

Asian

|

131 (17.8)

|

29 (13.9)

|

|

5 (5.1)

|

|

|

Indigenous

|

7 (1.0)

|

3 (1.4)

|

|

2 (2.0)

|

|

|

All others

|

43 (5.9)

|

18 (8.6)

|

|

4 (4.1)

|

|

|

Ethnicity

|

.1796

|

|

.0373a

|

|

Hispanic

|

74 (10.1)

|

16 (7.7)

|

|

3 (3.1)

|

|

|

Non-Hispanic

|

660 (89.9)

|

193 (92.3)

|

|

95 (96.9)

|

|

|

Practice rurality (RUCC)

|

|

Metropolitan

|

626 (86.1)

|

168 (26.8)

|

.0487a

|

71 (11.3)

|

.0012a

|

|

Practice region

|

.0314a

|

|

.0019a

|

|

Northeast

|

85 (11.7)

|

26 (12.6)

|

|

10 (10.4)

|

|

|

South

|

207 (28.4)

|

41 (19.9)

|

|

11 (11.5)

|

|

|

Midwest

|

192 (26.4)

|

66 (32.0)

|

|

35 (36.5)

|

|

|

West

|

244 (33.5)

|

73 (35.4)

|

|

40 (41.7)

|

|

|

Program

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Residency region

|

.0392a

|

|

.0077a

|

|

Northeast

|

85 (11.7)

|

26 (12.6)

|

|

10 (10.4)

|

|

|

South

|

207 (28.4)

|

41 (19.9)

|

|

11 (11.5)

|

|

|

Midwest

|

192 (26.4)

|

66 (32.0)

|

|

35 (36.5)

|

|

|

West

|

244 (33.5)

|

73 (35.4)

|

|

40 (41.7)

|

|

|

Residency community served

|

.3190

|

|

.9167

|

|

Inner city

|

111 (15.7)

|

28 (13.7)

|

|

13 (13.7)

|

|

|

Rural

|

99 (14.0)

|

36 (17.6)

|

|

14 (14.7)

|

|

|

Suburban

|

237 (33.6)

|

67 (32.8)

|

|

31 (32.6)

|

|

|

Urban/suburban

|

259 (36.7)

|

73 (35.8)

|

|

37 (38.9)

|

|

|

Residency size

|

|

|

.0456a

|

|

.0292a

|

|

<19 residents

|

120 (16.8)

|

27 (13.0)

|

|

9 (9.3)

|

|

|

19–31 residents

|

374 (52.5)

|

101 (48.8)

|

|

45 (46.4)

|

|

|

>31 residents

|

219 (30.7)

|

79 (38.2)

|

|

43 (44.3)

|

|

|

Residency type

|

|

|

.3910

|

|

.3910

|

|

University-based

|

166 (23.3)

|

44 (21.3)

|

|

17 (17.5)

|

|

|

Community-based, universityaffiliated

|

451 (63.3)

|

135 (65.2)

|

|

70 (72.2)

|

|

|

Community-based, not affiliated

|

56 (7.9)

|

13 (6.3)

|

|

6 (6.2)

|

|

|

Military

|

30 (4.2)

|

13 (6.3)

|

|

4 (4.1)

|

|

|

Primary clinic training site

|

|

|

.2943

|

|

.3985

|

|

Hospital-based

|

370 (51.9)

|

108 (52.2)

|

|

47 (48.5)

|

|

|

Nonhospital, nonprofit

|

155 (21.7)

|

36 (17.4)

|

|

18 (18.6)

|

|

|

Nonhospital, for-profit

|

52 (7.3)

|

16 (7.7)

|

|

8 (8.2)

|

|

|

FQHC

|

109 (15.3)

|

36 (17.4)

|

|

19 (19.6)

|

|

|

Military

|

23 (3.2)

|

8 (3.9)

|

|

3 (3.1)

|

|

|

Other

|

4 (0.6)

|

3 (1.5)

|

|

1 (2.0)

|

|

Single-residency institution

|

265 (37.2)

|

87 (42.0)

|

.1715

|

48 (49.5)

|

.0279a

|

|

Presence of an OB/GYN residency

|

292 (41.7)

|

70 (34.3)

|

.0174a

|

25 (26.0)

|

.0015a

|

|

Accreditation in 2015

|

.3910

|

|

.4809

|

|

ACGME

|

538 (75.6)

|

162 (78.6)

|

|

77 (80.2)

|

|

|

Dual ACGME/AOA

|

171 (24.0)

|

44 (21.4)

|

|

19 (19.8)

|

|

|

AOA only

|

3 (0.4)

|

|

|

|

Practicing maternity care

|

Maternity care

|

Performing deliveries

|

Delivery

|

Total

|

|

N=214 n (%)

|

P values

|

N=99 n (%)

|

P values

|

N=752 n (%)

|

|

6 + FM OB faculty

|

136 (65.7)

|

<.0001a

|

81 (83.5)

|

<.0001a

|

359 (50.4)

|

|

4 + months OB training

|

92 (44.4)

|

<.0001a

|

60 (61.9)

|

<.0001a

|

238 (33.4)

|

|

>80 deliveries

|

122 (57.3)

|

<.0001a

|

84 (84.8)

|

<.0001a

|

231 (30.8)

|

|

Continuity delivery requirement

|

166 (81.0)

|

.1071

|

77 (79.4)

|

.5343

|

545 (76.9)

|

|

Presence of group prenatal visits

|

63 (30.7)

|

.0943

|

35 (36.1)

|

.0250a

|

186 (26.2)

|

|

Presence of FM-OB fellowship

|

88 (67.7)

|

.0288a

|

31 (41.9)

|

.0261a

|

100 (20.0)

|

|

Presence of FM-OB track

|

45 (30.4)

|

.0003a

|

42 (73.7)

|

<.0001a

|

266 (59.5)

|

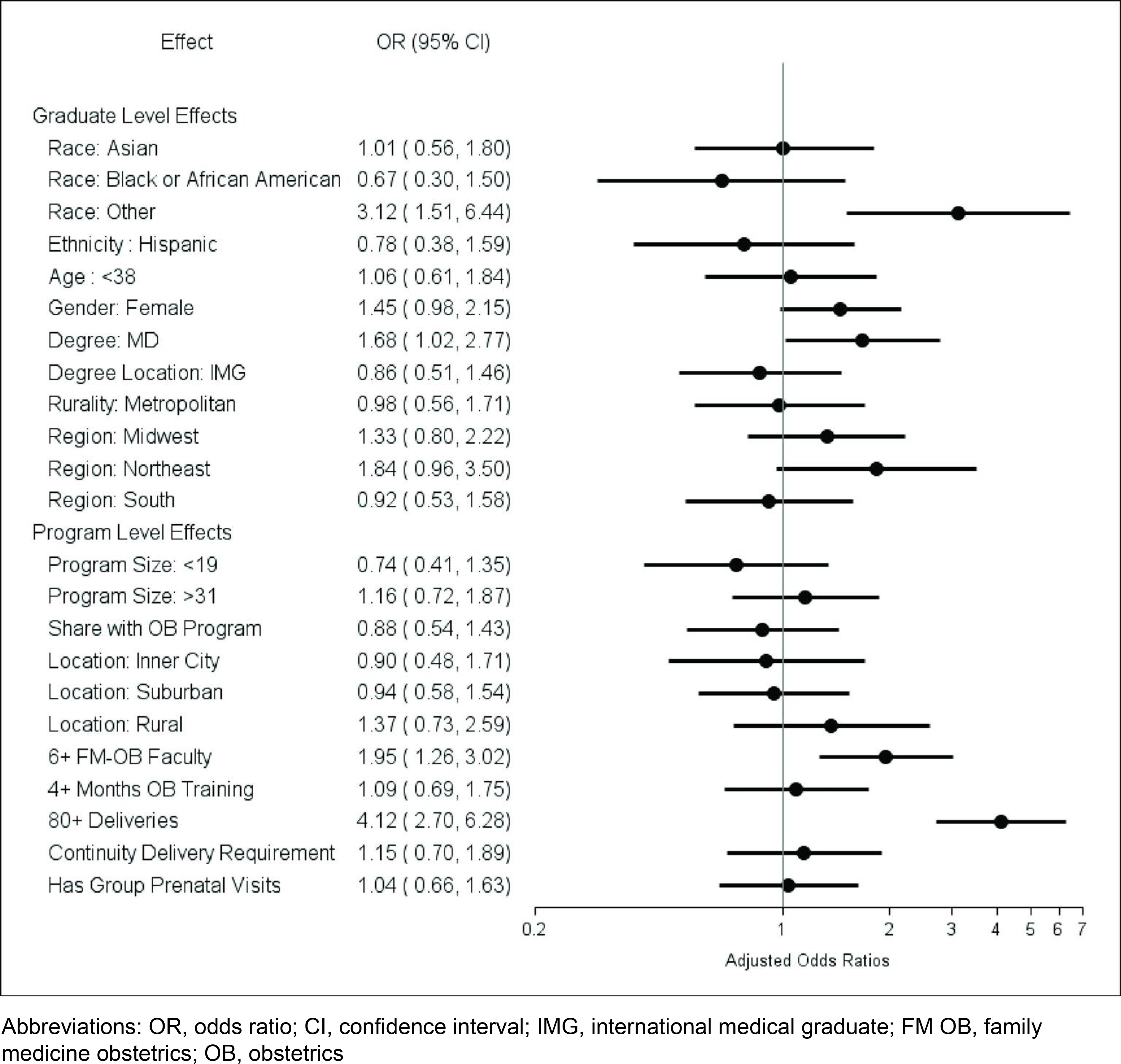

In multivariate analysis of associations with graduates providing maternity care (Figure 2), the personal characteristics with higher odds of providing maternity care were the graduate reporting a race in the Other category (3.12 [1.51, 6.44]) and having an MD medical degree (1.68 [1.02, 2.77]). No program characteristics were associated with providing maternity care. Program processes associated with significantly higher odds of providing maternity care after graduation were exposure to at least six faculty performing or supervising deliveries (1.95 [1.26, 3.02]) and performance of at least 80 deliveries during residency (4.12 [2.70,6.28]).

In multivariate analysis of associations with graduates performing deliveries (Figure 3), the only personal characteristic with higher odds of performing deliveries was having an MD degree (2.66 [1.27, 5.58]). No program characteristics were associated with graduates performing deliveries. Program processes associated with significantly higher odds of graduates performing deliveries after residency were exposure to at least six faculty performing or supervising deliveries (3.90 [1.91, 8.00]) and performing at least 80 deliveries during residency (12.61 [6.35,25.04]).

In this first large national prospective study, we found a strong and significant association between graduates performing at least 80 deliveries during residency and caring for pregnant patients and performing deliveries in practice 3 years after graduation. Four or more months of required obstetrics training during residency was associated with performing deliveries only. The strength of the associations we found between delivery volume during residency and providing pregnancy care in practice was striking; graduates providing maternity care were more than six times as likely to have performed more than 80 deliveries in training, and graduates performing deliveries were more than 12 times as likely. These findings align with the July 2023 ACGME family medicine residency requirements for delivery competency.11

The national conversation about pregnancy care training requirements in family medicine residency has been characterized by lively debate and a reckoning with our nation’s complex and evolving systems of care for pregnant people (ie, streamlining and concentrating clinician time in a single setting).20 The literature has suggested that producing more well-trained family medicine graduates who choose to include pregnancy care in their practice could help to address maternity care deserts, reduce birth-related disparities, and promote health throughout the life cycle.21,35,36 To accomplish this goal, a deeper understanding of the impact of specific training elements on future pregnancy care practice will be needed, especially given limited pregnancy care training opportunities in some residency programs. In 2023, the ACGME Family Medicine Review Committee implemented major changes to the pregnancy care training requirements, attempting to delineate the specific training needed for family physicians to provide outpatient pregnancy care and the additional training required for a family physician to independently manage intrapartum patients and perform vaginal deliveries. The concern in the maternity care community is whether these new standards are based on evidence. We believe this study provides the first step toward answering this question.

While our results clearly suggest that training time and delivery volume matter, we are not suggesting that volume or time guarantees competency or is a surrogate for it. The development of competency is a complex process, requiring the interplay of knowledge, skills, behaviors, and values.37–39 Many factors impact the speed with which competency develops, including learner aptitude, the degree of active learner engagement, the sequence and progression of learning experiences and graduated independence, and the quality of feedback provided in response to direct observation.40,41 National standards and specific, consistent methods of assessing competency remain the gold standard for ensuring that graduates are prepared for specific aspects of family medicine practice. However, ensuring adequate volume and training time creates conditions with sufficient breadth and clinical complexity to allow competency to develop. While recognizing the likelihood of outliers, we believe that our results shed light on the volume and exposures typically needed to support the development of competency in providing care during pregnancy and the confidence needed for graduates to choose to provide this care after graduation.

We also found that exposure to six or more faculty performing or supervising deliveries was strongly associated with graduates providing maternity care and performing deliveries in practice. In addition to ensuring that residents receive robust clinical teaching, procedural training, and sufficient feedback on progress toward maternity care competency, a faculty cohort of this size provides powerful role modeling of sustainable family medicine practice that includes pregnancy care. This finding may address some resident concerns about lifestyle factors associated with providing pregnancy care. Of note, according to our results, exposure to one faculty member engaged in pregnancy care as required by previous versions of the ACGME family medicine requirements11 was not associated with graduates providing such care in practice.

Our study found that a continuity delivery requirement was not significantly associated with graduates providing pregnancy care. Similarly, exposure to group prenatal visits was not significantly associated with graduates providing pregnancy care, when controlling for other residency curricula and structures in multivariate analyses. Both these findings differ from the findings of previous studies of initial graduate practice as reported by program directors, but not measuring outcomes directly from graduates.12,41 We are not suggesting that continuity delivery or group prenatal visit experiences are not valuable. However, our findings may provide important information for establishing curricular priorities when programs aim to produce graduates who provide pregnancy care. Residency characteristics were not a significant factor in multivariate analyses. This finding suggests that developing residency curricula that produce graduates who provide pregnancy care may be possible in a wide variety of programs.

The most notable strength of this study is that it examined graduate outcomes related to providing pregnancy care and deliveries in family medicine practice, and comprehensively explored associations with specific residency processes and exposures. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to do so. We explored the impact of a full range of pregnancy care training experiences, including advanced experiences, where previous studies mainly focused on minimum training requirements. By using national samples of both program directors and residency graduates, we were able to explore outcomes and associations in a wide variety of residency settings, which suggests that our findings are generalizable.

As with all survey research, our study may have been limited by recall bias. However, this was likely minimized by the timing of survey administration. Social desirability bias was possibly related to the desire to positively portray program attributes and graduate practice patterns. The response rate to the NGS was lower than desired, likely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, which made the analysis of certain items challenging due to the smaller number of responses. The intersection of multiple contributing factors is complex and was difficult to fully assess. Lastly, nonparticipation by program directors excluded the responses of their program’s graduates in the matched analysis, which could introduce bias. While program directors were representative of residencies in 2018,25 merging with NGS respondents resulted in a small bias toward larger programs. Variability in program director participation suggests a need for improved engagement and reporting accuracy. Increasing CERA survey completion within the program director community is essential for capturing comprehensive residency characteristics that can inform future training requirements and policies, including those established by ACGME.

Areas for future study should include continued evaluation of graduate practice outcomes following the introduction of the July 2023 ACGME requirements, including outcomes related to the requirements for providing comprehensive pregnancy care (inclusive of vaginal deliveries). Although we found the presence of advanced training experiences such as FM-OB fellowships and areas of concentration were positively associated with graduate pregnancy care provision, the number of responses for those items was small. Further investigation specifically focusing on the impact of these advanced training opportunities may provide important information about their impact on graduate practice outcomes, as well as on the graduates of residencies with which they are associated. Although residency characteristics were overall not significant in our study, continued investigation is warranted, considering the unprecedented volume of newly accredited programs that are emerging nationally in a variety of settings and affiliations. Finally, further investigation of the impact of family medicine residency graduates who provide pregnancy care in rural and underresourced communities would further characterize their potential to increase access to this care and improve maternal and neonatal outcomes in these communities.

As the call becomes louder for family medicine residencies to train more graduates who provide pregnancy care in order to mitigate worsening workforce shortages in many US communities, we believe our findings provide important guidance for residency programs and their sponsoring institutions. Programs seeking to train graduates who provide pregnancy care should prioritize building or maintaining a sustainable complement of family medicine faculty who perform deliveries (our study suggests six or more). Our findings suggest that these programs should ensure that their residents perform at least 80 vaginal deliveries during residency, and they should provide at least 4 months of obstetrics training for residents who intend to provide intrapartum care and deliveries. To realize potential workforce gains, sponsoring and partnering institutions will need to provide the support and resources for developing and maintaining these curricular offerings. Our study suggests that these residency elements can overcome program characteristics such as geographic region, affiliation, and the presence of an OB/GYN residency program in sponsoring institutions, opening the door for programs in a wide variety of settings to train graduates who will provide pregnancy care in their future practice (Appendix A and Appendix B).

Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) Annual Meeting, Tampa FL, May 2, 2023; North American Primary Care Research Group Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA, October 30, 2023; STFM Annual Meeting, Los Angeles, CA, May 2, 2024; American Academy of Family Physicians Residency Leadership Summit, Kansas City, MO, March 25, 2025.

The American Board of Family Medicine Foundation provided financial support for Dr Wendy Barr.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Sebastian Tong, MD, MPH, Tyler Barreto, MD, and Aimee Eden, PhD, who assisted with developing the CERA program director survey questions.

References

-

Tong STC, Makaroff LA, Xierali IM, et al. Proportion of family physicians providing maternity care continues to decline. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(3):270–271.

-

Rayburn WF. The Obstetrician-Gynecologist Workforce in the United States: Facts, Figures, and Implications, 2017. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2017.

-

American Board of Family Medicine. National family medicine residency graduate reports.

-

Cohen D, Coco A. Declining trends in the provision of prenatal care visits by family physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(2):128–133.

-

Chen FM, Huntington J, Kim S, Phillips WR, Stevens NG. Prepared but not practicing: declining pregnancy care among recent family medicine residency graduates. Fam Med. 2006;38(6):423–426.

-

Hoyert D. Maternal mortality rates in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics Health E-Stats, 2024; 2022.

-

Kozhimannil KB, Interrante JD, Henning-Smith C, Admon LK. Rural-urban differences in severe maternal morbidity and mortality in the US, 2007-15. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(12):2077–2085.

-

March of Dimes. Nowhere to Go: Maternity Care Deserts Across the US. 2024.

-

Barreto TW, Eden AR, Petterson S, Bazemore AW, Peterson LE. Intention versus reality: family medicine residency graduates’ intention to practice obstetrics. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(4):405–406.

-

Barreto TW, Eden A, Hansen ER, Peterson LE. Opportunities and barriers for family physician contribution to the maternity care workforce. Fam Med. 2019;51(5):383–388.

-

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. ACGME; 2025.

-

Sutter MB, Prasad R, Roberts MB, Magee SR. Teaching maternity care in family medicine residencies: what factors predict graduate continuation of obstetrics? A 2013 CERA program directors study. Fam Med. 2015;47(6):459–465.

-

Rayburn WF, Petterson SM, Phillips RL. Trends in family physicians performing deliveries, 2003-2010. Birth. 2014;41(1):26–32.

-

Barreto TW, Eden AR, Hansen ER, Peterson LE. Barriers faced by family medicine graduates interested in performing obstetric deliveries. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(3):332–333.

-

Godwin M, Hodgetts G, Seguin R, MacDonald S. The Ontario family medicine residents cohort study: factors affecting residents’ decisions to practise obstetrics. CMAJ. 2002;166(2):179–184.

-

Dresden GM, Baldwin L-M, Andrilla CHA, Skillman SM, Benedetti TJ. Influence of obstetric practice on workload and practice patterns of family physicians and obstetriciangynecologists. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(Suppl 1):S5–11.

-

Tong ST, Makaroff LA, Xierali IM, Puffer JC, Newton WP, Bazemore AW. Family physicians in the maternity care workforce: factors influencing declining trends. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(9):1576–1581.

-

Rayburn W. Who will deliver the babies? Identifying and addressing barriers. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(4):402–404.

-

Fashner J, Cavanagh C, Eden A. Comparison of maternity care training in family medicine residencies 2013 and 2019: a CERA program directors study. Fam Med. 2021;53(5):331–337.

-

Bazemore A, Petterson S, Peterson LE. More comprehensive care among family physicians is associated with lower costs and fewer hospitalizations. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(3):206–213.

-

Goldstein JT, Hartman SG, Meunier MR, et al. Supporting family physician maternity care providers. Fam Med. 2018;50(9):662–671.

-

Tong ST, Eden AR, Morgan ZJ, Bazemore AW, Peterson L. The essential role of family physicians in providing cesarean sections in rural communities. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(1):10–11.

-

Barreto T, Jetty A, Eden AR, Petterson S, Bazemore A, Peterson LE. Distribution of physician specialties by rurality. J Rural Health. 2021;37(4):714–722.

-

Worth A. The numbers quandary in family medicine obstetrics. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(1):167–168.

-

Barr WB, Peterson LE, Fleischer S, Seehusen DA. National family medicine residency outcomes project methodology. PRiMER. 2024;8:52.

-

-

Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW. Creating a centralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257–260.

-

Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. CERA ABFM linked residency outcomes research study. 2018.

-

Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. CAFM Educational Research Alliance (CERA).

-

Mitchell KB, Maxwell L, Miller T. The national graduate survey for family medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(6):595–596.

-

Weidner AKH, Chen FM, Peterson LE. Developing the national family medicine graduate survey. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(5):570–573.

-

Peterson LE. Using the family medicine national graduate survey to improve residency education by monitoring training outcomes. Fam Med. 2021;53(7):622–625.

-

USDA Economic Research Service. Rural-Urban Continuum Codes.

-

SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® 15.3 User’s Guide. 2023.

-

Thomson C, Goldstein JT, Pecci CC, Oluyadi F, Shields SG, Farahi N. Reply to “comparison of maternity care training in family medicine residencies 2013 and 2019: a CERA program directors study”. Fam Med. 2022;54(1):69.

-

Barr WB, DeMarco MP. Family medicine obstetrics: answering the call. Ann Fam Med. 2024;22(5):367–368.

-

Misra S, Iobst WF, Hauer KE, Holmboe ES. The importance of competency-based programmatic assessment in graduate medical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(2 Suppl):113–119.

-

Nguyen VT, Losee JE. Time- versus competency-based residency training. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(2):527–531.

-

Magee SR, Eidson-Ton WS, Leeman L, et al. Family medicine maternity care call to action: moving toward national standards for training and competency assessment. Fam Med. 2017;49(3):211–217.

-

Holmboe ES. Realizing the promise of competency-based medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90(4):411–413.

-

Barr WB, Tong ST, LeFevre NM. Association of group prenatal care in US family medicine residencies with maternity care practice: a CERA secondary data analysis. Fam Med. 2017;49(3):218–221.

There are no comments for this article.