An adverse childhood experience (ACE) score measures negative occurrences, such as abuse, neglect, and instability, before age 18.1–4 Similarly, a benevolent childhood experience (BCE) score measures positive occurrences, such as social support and stability.2–4 Nationally, 63.9% of adults report one or more ACE occurrences; 17.3% report four or more ACE occurrences.5 Understanding and addressing the impact of ACEs on medical students is vital. Research shows that ACEs negatively impact health while BCEs have positive effects, with high BCE scores potentially offsetting the adverse outcomes of high ACE scores.3,5,6 Some studies have suggested that childhood experiences affect depression and behavioral health, while others have explored their influence on provider-patient relationships and practice preferences.7–11 However, little is known about the combined influence of ACE and BCE scores on coping mechanisms. Given that coping strategies can be healthy or unhealthy, this study explored how ACEs and BCEs shape adult coping in preclinical medical students, with implications for early intervention.12,13

BRIEF REPORTS

The Link Between Childhood Experiences and Coping Mechanisms in Medical Students

Gabrielle Plata, MS | Neeti Swami | Angelica Nibo | Haley Lewsey | Aya Bou Fakhreddine, MS | David Trotter, PhD | Elisabeth Conser, MD

Fam Med. 2025;57(10):732-736.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2025.195277

Background and Objectives: This study explored the influence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and benevolent childhood experiences (BCEs) on coping mechanisms among medical students. It aimed to determine the association between ACE and BCE scores and their impact on coping behaviors, recognizing the potential for interventions to promote healthier coping strategies.

Methods: We used data collected from the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine P3-1 Honors Project Omnibus Survey among preclinical medical students. Participants self-reported ACE and BCE scores, along with the frequency and perceived effectiveness of both healthy and unhealthy coping mechanisms.

Results: The analysis showed a significant negative correlation between ACE and BCE scores, indicating that higher ACE scores corresponded to lower BCE scores. Social support emerged as the most common healthy coping mechanism, while self-blame stood out as the predominant unhealthy coping strategy. Additionally, we found statistically significant associations between BCE scores and the use of coping strategies such as spiritual support, self-blame, and isolation.

Conclusions: Findings imply that high ACE scores correlate with impulsive behaviors. Conversely, high BCE scores are associated with lower tendencies for self-blame, isolation, and impulsive activities, suggesting protective factors. The study underscores the need for interventions to foster healthy coping mechanisms, particularly for individuals with high ACE scores.

Data were gathered via the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC) School of Medicine P3-1 Honors Project Omnibus Survey, which was exempt from review by the institutional review board. This survey was administered to preclinical medical students in Lubbock, Texas, and it garnered responses from 138 participants. Respondents were tasked with calculating their ACE and BCE scores based on a supplied assessment. Students self-reported their usage frequency and perceived efficacy of both healthy and unhealthy coping mechanisms using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = always). The survey provided examples of coping mechanisms falling within each of the following categories: friend support, plan making, reframing, physical exercise, spiritual support, blaming, avoidance, isolation, venting, and impulses.

We analyzed the data using Spearman’s correlation coefficient to examine the correlation between ACE and BCE scores. We estimated adjusted odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals using ordinal logistic regression models to investigate possible relationships between ACE and BCE scores and the use of coping mechanisms. We adjusted these models for BCE scores when examining the association between ACE score and each coping behavior, and for ACE scores when investigating the association between BCE scores and coping behaviors.

Of 138 preclinical medical students surveyed, 44% identified as female, 54% as male, and 1% as gender nonconforming or chose not to disclose. Students fell into the following age groups: 21–23 (33%), 24–26 (51%), 27–30 (12%), and 31+ (4%). The racial/ethnic makeup of respondents was 57% Caucasian/White, 17% Asian, 7% Hispanic/Latino, 6% Black/ African American, 2% Middle Eastern/North African, 9% multiple selected, and 2% chose not to disclose.

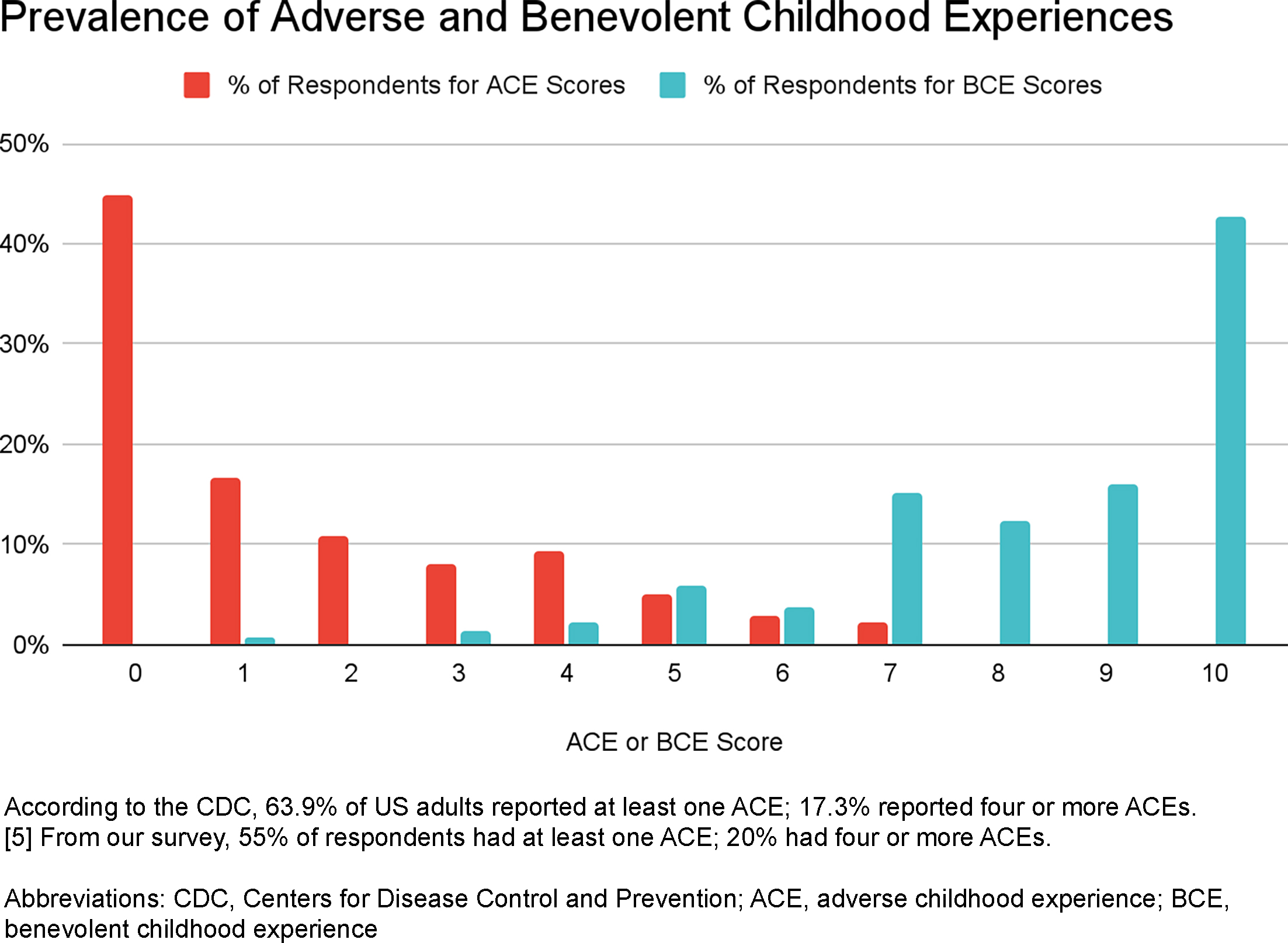

Fifty-five percent of respondents had one or more ACE occurrences, and 20% of respondents had four or more ACE occurrences. Every respondent had one or more BCE occurrences (Figure 1). Forty-five percent of respondents had no ACE occurrences, 43% had all 10 BCEs, and 30% had both those scores. We found a statistically significant negative correlation between the ACE score and the BCE score with an r value of r=–0.55 (P value <0.01), meaning that as the ACE score increased, the BCE score decreased.

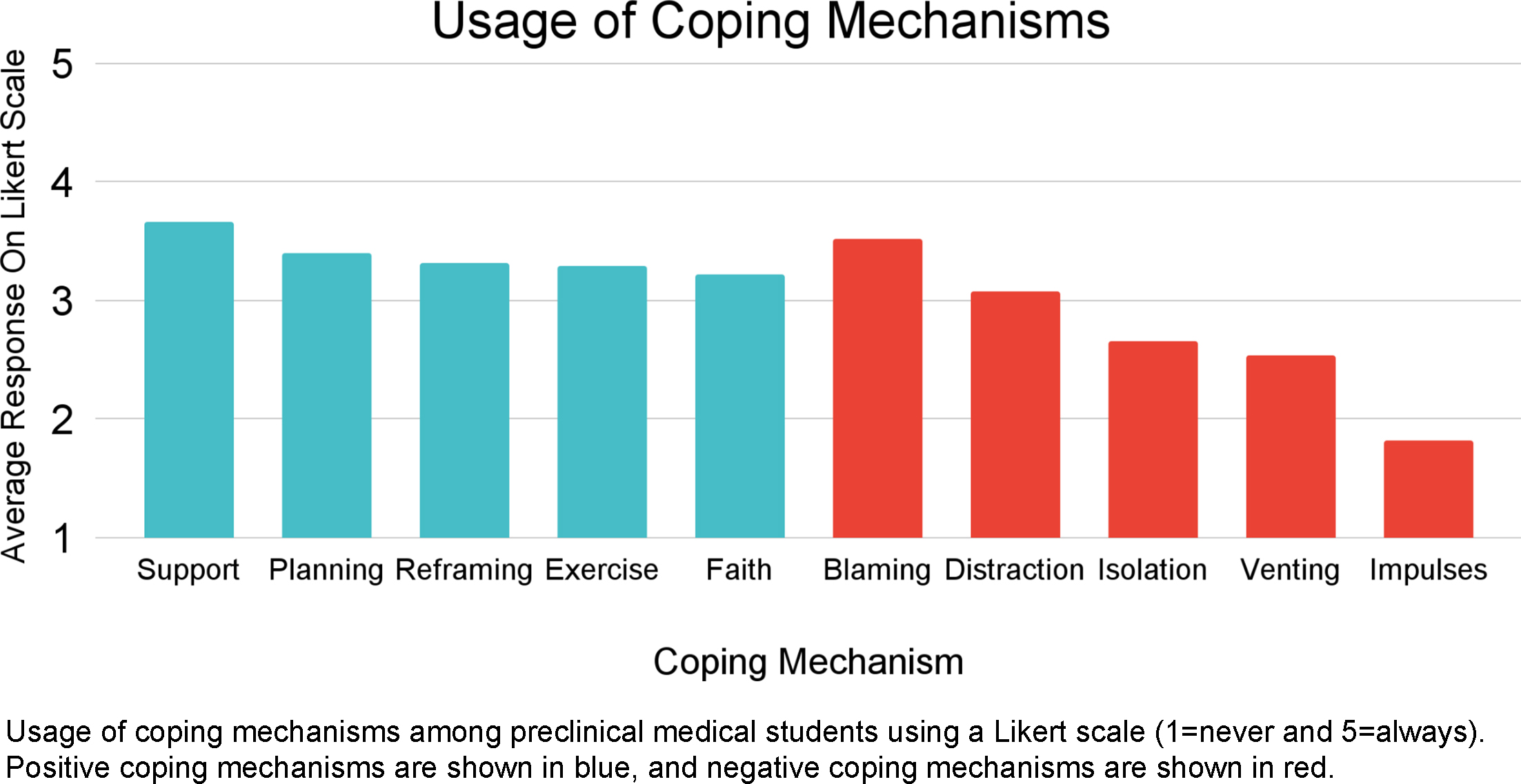

The most frequently utilized healthy and unhealthy coping mechanisms, measured on a 5-point Likert scale, were social support (3.67) and blaming (3.52; Figure 2). Aside from blaming, respondents generally used healthy coping mechanisms more frequently than unhealthy coping mechanisms.

Adjusted odds ratios for coping mechanisms as related to both ACE and BCE scores demonstrated that spiritual support, self-blaming, and isolation were all significantly associated with the BCE score. Each one-unit increase in BCE score was associated with an increased adjusted odds of using spiritual support by 21%, and decreased adjusted odds of using self-blaming and isolation by 18% and 21%, respectively (Table 1). Additionally, impulsive behavior was significantly associated with both ACE and BCE scores. Each one-unit increase in ACE score was associated with an increased adjusted odds of impulsive behavior by 29%, while each one-unit increase in BCE score was associated with decreased adjusted odds of impulsive behavior by 22% (Table 1). We also investigated a possible relationship between race/ethnicity and ACE and BCE scores and found no statistically significant differences across racial or ethnic categories.

|

Survey question topic |

ACE score Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

BCE score Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

|

Social support |

0.91 (0.75–1.09) |

1.14 (0.95–1.37) |

|

Plan making |

0.94 (0.77–1.13) |

1.12 (0.93–1.34) |

|

Reframing |

1.09 (0.9–1.32) |

1.05 (0.87–1.27) |

|

Physical exercise |

1.18 (0.98–1.42) |

1.1 (0.92–1.32) |

|

Spiritual support |

0.98 (0.81–1.18) |

1.21 (1.02–1.46)a |

|

Blaming |

1.1 (0.91–1.34) |

0.82 (0.67–0.99)a |

|

Avoidance |

1.14 (0.95–1.37) |

0.85 (0.7–1.03) |

|

Isolation |

1.14 (0.94–1.38) |

0.79 (0.65–0.96)a |

|

Venting |

0.97 (0.81–1.17) |

1.06 (0.87–1.28) |

|

Impulses |

1.29 (1.07–1.56)a |

0.78 (0.64–0.94)a |

|

Capable of managing stressors |

0.97 (0.8–1.18) |

1.16 (0.95–1.42) |

|

Healthy coping skills |

0.95 (0.79–1.15) |

1.12 (0.94–1.35) |

|

Effective coping skills |

0.92 (0.76–1.12) |

1.17 (0.96–1.42) |

Adjusted odds ratios for use and perception of coping mechanisms relative to ACE score, adjusted for BCE score, and relative to BCE score, adjusted for ACE score. Odds ratios are shown adjacent to 95% confidence intervals in parentheses.

aStatistically significant.

Abbreviations: ACE, adverse childhood experience; BCE, benevolent childhood experience; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio

The results suggest that high ACE scores, after experiencing abuse or instability, may lead to impulsive behaviors such as excessive spending, binge drinking, or extreme dieting. Conversely, high BCE scores, with support often found in spirituality, are linked to lower self-blame, isolation, and impulsivity. Positive role models and environments appear to offset the effects of ACEs by fostering autonomy, control, self-esteem, and a sense of belonging.

Many medical students have zero ACEs, potentially reflecting social and educational advantages they may have experienced in childhood.14 However, some students have a low ACE and a low BCE score. Several studies have suggested that a low BCE score may predict worse mental health outcomes in adulthood independent of ACE score.2,15–17

Additionally, 20% of respondents, like 17.3% of the general population, have four or more ACEs, predisposing them to several chronic conditions and unhealthy coping.1,5 One important consideration for ACEs is racially disadvantaged status. Though our study found no significant racial/ethnic differences, national data show unequal ACE exposure. Larger studies may better assess how ACEs, BCEs, and coping differ across disadvantaged groups.18

Further research is needed to clarify how other factors influence coping development. While we did not assess the use of TTUHSC-specific resources such as student counseling or wellness sessions, these likely supported positive coping. We also found a significant link between ACE scores and impulsive behaviors (eg, alcohol use, spending, binge eating), though substance use was not measured separately. In broader populations, high ACE scores are tied to greater risk for substance use, depression, and suicide.7,19–22 The same may be true for medical students and physicians, but research on the effect of ACEs on the incidence of substance use disorders in this population is limited.

This study highlights the need for both further research and intervention. Given the higher suicide rate among physicians and the link between ACEs and poor mental health, our findings suggest that screening ACE/BCE scores may help identify at-risk medical students and guide targeted support.19

Limitations of this study included the nongeneralizable sample set, age of respondents (most under 35), disproportionately low responses from disadvantaged racial groups, subjectivity of question interpretation, and possible fatigue from the length of the full survey. Additionally, the prompt “What do you usually do when you experience a stressful event?” was accidentally omitted.

While ACEs cannot be changed, research has suggested that students with high ACEs benefit from mental health resources.23 Given this, we have created and implemented a series of activity-based interventions to help replace negative coping habits with positive ones such as grounding techniques, mindfulness, and social connection. We plan to make our materials available for use by other institutions.

Understanding ACEs and BCEs in medical students can shed light on tendencies such as self-blame, isolation, impulsivity, or seeking spiritual comfort. When included in trauma-informed medical curricula, students may better recognize ACEs in themselves and in clinical encounters.24,25 Such curricula can further prepare future physicians for clinical manifestations, which commonly present in underserved populations.26

Finally, knowledge is power, but it is also a privilege. Beyond pediatricians, abuse specialists, and therapists, we can share ACE/BCE information with peers who may be unaware of its pertinence.

This study was presented at the following venues:

-

2023 Texas Pediatric Society Annual Meeting, September 28–October 1, 2023, Round Rock, Texas.

-

2024 Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Conference on Medical Student Education, February 9–11, 2024, Atlanta, Georgia.

Disclaimer: Views expressed do not reflect the views of affiliated institutions.

References

-

The original ACE study. https://nhttac-stage.acf.hhs.gov/soar/eguide/stop/adverse_childhood_experiences

-

Positive childhood experiences and adult mental and relational health in a statewide sample: associations across adverse childhood experiences levels. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(11):e193007.

-

ACEs and counterACEs: how positive and negative childhood experiences influence adult health. Child Abuse Neglect. 2019;96:104089.

-

Positive childhood experiences predict less psychopathology and stress in pregnant women with childhood adversity: a pilot study of the benevolent childhood experiences (BCEs) scale. Child Abuse Negl. 2018;78:19–30.

-

Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences among U.S. adults behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2011-2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(26):707–715.

-

Positive childhood experiences and ideal cardiovascular health in midlife: associations and mediators. Prev Med. 2017;97:72–79.

-

Association of adverse childhood experiences and depression among medical students: the role of family functioning and insomnia. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1134631.

-

Bidirectional associations between family conflict and child behavior problems in families at risk for maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 2022;133:105832.

-

Impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) and Childhood Protective Factors (CPF) on physical and mental health of medical students of a public sector medical university. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2025;5(2):e0004285.

-

Associations between adverse childhood experiences and medical students’ interest in careers: a single-setting study. Front Psychiatry. 2025;16:1483871.

-

Ghosts in the exam room, empathy, and physician well-being. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(5):529–531.

-

A count of coping strategies: a longitudinal study investigating an alternative method to understanding coping and adjustment. PLoS One. 2017;12(10).

-

Adverse childhood experiences and coping strategies: identifying pathways to resiliency in adulthood. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2019;32(5):594–609.

-

Study finds medical students disproportionately come from affluent backgrounds. MPR News. 2022. Accessed March 21, 2022. https://www.mprnews.org/story/2022/03/21/study-finds-medical-students-disproportionatelycome-from-affluent-backgrounds

-

A systematic review of positive childhood experiences and adult outcomes: promotive and protective processes for resilience in the context of childhood adversity. Child Abuse Negl. 2023;144:106346.

-

Positive adult experiences as turning points for better adult mental health after childhood adversity. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1223953.

-

Positive childhood experiences and adult health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2023;152(1).

-

The prevalence of adverse childhood experiences, nationally, by state, and by race or ethnicity. Child Trends. 2018. Accessed May 25, 2025. https://www.childtrends.org/publications/prevalence-adversechildhood-experiences-nationally-state-race-ethnicity

-

Suicide among physicians and health-care workers: a systematic review and metaanalysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(12).

-

Assessment of risk factors for suicide among US health care professionals. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(8):713–721.

-

Adverse childhood experience patterns, major depressive disorder, and substance use disorder in older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25(3):484–491.

-

Adverse childhood experiences in medical students: implications for wellness. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(4):369–374.

-

Exploring resilience factors in medical students with adverse childhood experiences: a pilot study. Acad Psychiatry. 2022;46(2):218–222.

-

Adverse childhood experiences and trauma informed care: the future of health care. Pediatr Res. 2016;79(1-2):227–233.

-

Trauma-informed medical education (TIME): advancing curricular content and educational context. Acad Med. 2021;96(5):661–667.

-

Trauma and resilience informed research principles and practice: a framework to improve the inclusion and experience of disadvantaged populations in health and social care research. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2023;28(1):66–75.

Lead Author

Gabrielle Plata, MS

Affiliations: Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine, Lubbock, TX

Co-Authors

Neeti Swami - Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine, Lubbock, TX

Angelica Nibo - Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine, Lubbock, TX

Haley Lewsey - Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine, Lubbock, TX

Aya Bou Fakhreddine, MS - Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine, Lubbock, TX

David Trotter, PhD - Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine, Lubbock, TX

Elisabeth Conser, MD - Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine, Lubbock, TX

Corresponding Author

Elisabeth Conser, MD

Correspondence: Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine, Lubbock, TX

Email: Elisabeth.Conser@ttuhsc.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.