Background and Objectives: Prior research showed that many clerkship directors (CDs) felt that the role benefited their careers but lacked adequate protected time and administrative support. Given family medicine faculty demographics, women are overrepresented in this role, while Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous faculty are underrepresented in medicine (URiM) and as CDs. Here we explore characteristics of US CDs and perceived benefits and challenges of the role.

Methods: We included 10 questions about CD time allocation and role perceptions in the 2024 Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance survey of CDs.

Results: Forty-eight percent (76/158) of CDs were eligible for analysis, of which 57% (46/76) were women and 9% (7/76) were URiM. These US CDs reported that the role increased prospects for promotion (86%) and attaining professional goals (93%); only 33% felt that the role increased compensation. Multivariate analysis showed years as CD increased the odds of academic promotion. CDs reported 1.5 days per week protected time but spent 2 days per week for the role; women spent more time than men (P = 0.04). Only one-third had any protected scholarship time, with women having less time than men (P = 0.02). Women CDs served half as many years as men (P = 0.01).

Conclusions: CDs valued the role for promotion and career advancement. However, they felt inadequately compensated and reported insufficient time for the role and for scholarship. Given the importance of clerkships for recruiting students into family medicine, it is critical to ensure adequate protected time, scholarship time, and commensurate compensation to attract and retain excellent faculty for the CD role.

Clerkship directors (CDs) serve an important role for medical students and family medicine departments. High-quality family medicine clerkships are positively associated with students matching into family medicine—an important consideration for addressing primary care shortages in the United States.1,2 In 2003, most internal medicine CDs felt that the position benefited their careers, with higher positive associations for CDs with adequate salary and administrative coordinator support as well as clearly defined responsibilities.3 In 2007 in seven clinical fields, including family medicine, CDs agreed that the role increased their overall job satisfaction and, to a lesser extent, enhanced career advancement.4 At the same time, these CDs reported devoting twice as much time to the role (33%) than the protected time given (16%), and average reported staff support was 0.69 full-time equivalent (FTE)4 rather than the 1.0 FTE recommended in the Alliance for Clinical Education [ACE] guidelines.5 However, these data were collected nearly two decades ago, and responsibilities of CDs have grown amidst an increasingly uncertain and complex health care environment.6,7 Garnering sufficient resources for the position in terms of time and administrative support has been a challenge across all specialties.8,9

Disparities in leadership representation, pay, and promotion are well-documented in family medicine for women and those underrepresented in medicine (URiM), although less pronounced than in academic medicine as a whole.10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) URiM definition includes Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous, but excludes Asian because data did not delineate Asian subpopulations and a large majority of Asian physicians do not classify as URiM. In 2020, women represented 53% of full-time family medicine faculty but only 42% of residency program directors and 30% of department chairs.16 At the same time, women were overrepresented among clerkship directors (61%) and associate residency program directors (58%).16 Also in 2020, family physicians who met the AAMC URiM definition made up 13% of family medicine faculty in medical schools and represented 16% of department chairs, 11% of program directors, and 12% of clerkship directors.16 Family medicine CD demographics changed significantly between 2012 and 2023 with increases in women CDs from 48.8%–60.2%,19 consistently higher than the overall percentage of women family medicine faculty, which increased from 46.1%–55.8% during that time.20,21 In contrast, the numbers of URiM CDs fluctuated over time ranging as high as 15.0% in 2021 but overall went from 7.2% in 2012 to 5.6% in 2023.19 With the exception of 2021, these were consistently lower than the overall percentage of URiM family medicine faculty, which increased slightly from 13.0%–14.2% over the same time.22,23

Considering the critical importance of the CD position and the shifting responsibilities and demographics of those serving in the role, we need updated data on perceptions of the benefits and challenges of the role and how it relates to time allocation and career trajectory. Data regarding any differences based on gender and URiM status are also lacking. The aim of this study is to help fill these gaps in the literature for family medicine CDs.

Design and Data Collection

The 2024 Council of Academic Family Medicine (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine clerkship directors collected cross-sectional data for this project. Seehusen et al described the infrastructure and methods for CERA annual omnibus surveys,24 and Kost et al detailed the specific methodology for the 2024 clerkship director study.25 This survey’s administration occurred June 4 to July 12, 2024. CERA surveys include standing questions that describe the CDs and their institutions. Table 1 contains the unique survey questions for this project. CERA data collection was approved by the American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board in May 2024 (IRB #19–366_A26); our analysis of de-identified data was exempt from IRB review.

Question stem |

Response options |

1. What best describes your credentials? |

Assistant professor (tenure track) Associate professor (tenure track) Full professor (tenure track) Assistant professor (nontenure track) Associate professor (nontenure track) Full professor (nontenure track) Clinical assistant professor Clinical associate professor Clinical professor Other |

2. Which of the following best describes how you became clerkship director? |

I applied for the role and was chosen. I volunteered for the role. I was asked to take on the role, and I accepted. I was assigned to take on the role. |

3. Based on the promotion criteria at my institution, I believe being a clerkship director increases my overall prospects for promotion.

4. Based on the compensation structure at my institution, I believe being a clerkship director increases my overall compensation per time worked.

5. I believe being a clerkship director will help me attain my professional goals. |

Strongly disagree Somewhat disagree Somewhat agree Strongly agree |

6. When you became clerkship director, what was the self-identified gender of the chair of your department? |

|

7. On average, how much time do you have per week built into your schedule for being a clerkship director?a

8. On average, how much time do you actually spend per week on clerkship director tasks?b

9. On average, how much time do you spend per week in direct patient care?

10. On average, how much time do you have protected per week for scholarly activities (research, grant writing, presentations, publications)? |

None 1/2 day 1 day 1½ days 2 days 2½ days 3 days 3½ days 4 days 4½ days 5 days or more |

CD Study Sample

CERA generated a list of 173 eligible survey recipients for 2024 (158 in the United States and 15 in Canada). A total of 91 responded. For the final sample, we excluded respondents who did not provide information on key variables and those located in Canada due to potential differences in training, salary, and promotion compared to the United States.

Analysis

We computed descriptive statistics (mean, median, n, %) and conducted bivariate comparisons using χ2, Fisher’s exact, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests. We described the CD role for the full sample and explored differences in self-reported CD gender by career stage (years since residency); academic rank; tenure track; gender of department chair; how the role was obtained (volunteered, applied, was asked and accepted, was assigned); time allocation for CD role, scholarly activities, and patient care; as well as perceptions about the CD role related to compensation, promotion, and professional goals. Finally, we used ordinal logistic regression to predict rank (assistant, associate, full professor) using these predictors: male gender; duration in CD role (in years); protected time for scholarship (in half days); protected time for CD role (in half days); and time since residency graduation (in years). Significance testing used α = 0.05. Stata version 14 (Stata Corp) was used for analysis.

Sample Description

Of the 173 eligible CDs, 91 (53%) responded to more than one survey question. We excluded two respondents who answered only part of the demographic questions, seven who did not answer the subset of questions related to our study aims, and the six Canadian respondents. Our final sample for analysis was 76 US CDs (48% of 158 US CDs). Kost et al25 published details of this survey methodology and noted that this sample was representative of CAFM family medicine clerkship directors.

Clerkship Director Role

Table 2 shows characteristics of CDs and their institutions. Of 76 respondents, more than half (57%) reported being female/women, most (75%) identified as White, and 9% identified as URiM. All CDs were physicians. Most respondents served at public medical schools, and about half were at institutions with class sizes of 150 or less. Institutions of participants were spread geographically throughout the United States, and all but one reported having mandatory family medicine clerkships. Most clerkships used a block design for the family medicine curriculum. At the time of becoming CD, nearly two-thirds of respondents had male department chairs.

CLERKSHIP DIRECTOR CHARACTERISTICS |

n (%) |

Gender |

Male/man |

33 (43) |

Female/woman |

43 (57) |

Other: did not disclose, genderqueer/gender nonconforming, nonbinary |

0 |

Race/ethnicity |

Hispanic/Latino/Spanish |

1 (1) |

Asian |

14 (18) |

Black/African American |

3 (4) |

White |

57 (75) |

Multiracial |

1 (1) |

Other: American Indian/Alaska Native/Indigenous, Middle Eastern/North African, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander |

0 |

Underrepresented in medicine (URiM) self-identification |

URiM |

7 (9) |

Non-URiM |

68 (89) |

Did not disclose |

1 (1) |

Physician’s degree |

Yes (eg, MD/DO) |

76 (100) |

No |

0 |

CLERKSHIP CHARACTERISTICS |

Clerkship design |

Block |

56 (74) |

Longitudinal |

10 (13) |

Block and longitudinal |

10 (13) |

Mandatory clerkship |

Yes |

75 (99) |

No |

0 |

Did not disclose |

1 (1) |

INSTITUTIONAL CHARACTERISTICS |

Type of institution |

Public |

53 (70) |

Private |

22 (29) |

Did not disclose |

1 (1) |

Medical school class size, number of students |

≤150 |

41 (54) |

>150 |

35 (46) |

Geographic location |

Northeast (New England, Middle Atlantic) |

16 (21) |

South (South Atlantic, East South Central, West South Central) |

27 (36) |

Midwest (East North Central, West North Central) |

18 (24) |

West (Mountain, Pacific) |

15 (20) |

Department chair gender at the time of CD hiring |

Male/man |

49 (64) |

Female/woman |

27 (36) |

Other: did not disclose, genderqueer/gender nonconforming, nonbinary |

0 |

When exploring URiM and gender differences in CD role responses, we noted that the self-reported URiM group was too small (n = 7) to compare against those who did not self-identify as URiM (n = 68, one respondent did not disclose). Statistical power was insufficient to draw conclusions about similarities or differences.

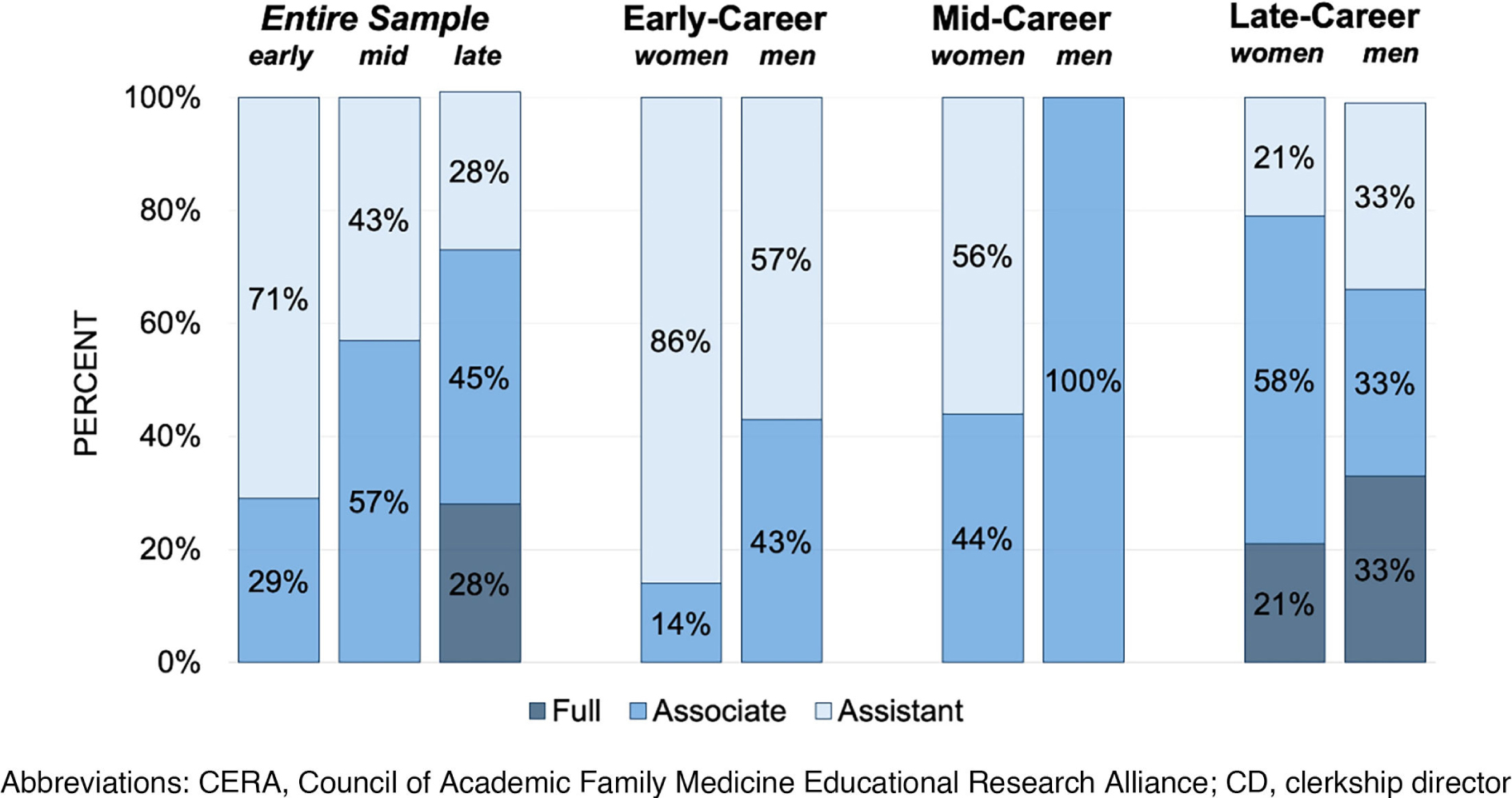

Table 3 describes respondents’ career credentials. Regarding academic rank, many CDs (41%) were assistant professors, and few (14%) were full professors. Less than a quarter (20%) of respondents were tenured or on the tenure track. About half of CDs were in the late stage of their career, defined as 15 or more years after graduation from residency. Among late-career CDs, nearly one-third remained assistant professors (Figure 1). Most CDs were asked to take on the role and accepted; others applied, volunteered, or were assigned to the position. Reported time in the CD role ranged from a few months to 26 years, with nearly one-third serving in the role more than 10 years.

|

Total (N = 76)* |

Women (N = 43)* |

Men (N = 33) |

P value |

|

n (%) or median (interquartile range, IQR) |

|

CLERKSHIP DIRECTOR CREDENTIALS |

Career stage |

.09 |

Early (0–7 years past residency) |

14 (18) |

7 (17) |

7 (21) |

|

Mid (8–14 years past residency) |

21 (28) |

16 (38) |

5 (15) |

|

Late (15+ years past residency) |

40 (53) |

19 (45) |

21 (64) |

|

Career rank |

.27 |

Assistant professor |

31 (41) |

20 (47) |

11 (33) |

|

Associate professor |

34 (45) |

19 (44) |

15 (45) |

|

Full professor |

11 (15) |

4 (9) |

7 (21) |

|

Tenured or tenure track, yes |

15 (20) |

8 (19) |

7 (21) |

.78 |

How CD role was obtained |

.55 |

Applied and was chosen |

22 (29) |

11 (26) |

11 (33) |

|

Volunteered |

6 (8) |

4 (9) |

2 (6) |

|

Was asked and accepted |

47 (62) |

28 (65) |

19 (58) |

|

Was assigned |

1 (1) |

0 |

1 (3) |

|

Total time in CD position, years |

.004** |

≤5 |

33 (43) |

22 (51) |

11 (33) |

|

6–10 |

21 (28) |

15 (35) |

6 (18) |

|

>10 |

22 (29) |

6 (14) |

16 (48) |

|

Median (IQR) |

6 (3–11.5) |

5 (3–9) |

10 (4–14) |

.01** |

TIME ALLOCATION |

Protected time for CD role, days/week |

.33 |

<1.5 |

32 (42) |

15 (35) |

17 (52) |

|

= 1.5 |

18 (24) |

12 (28) |

6 (18) |

|

>1.5 |

26 (34) |

16 (37) |

10 (30) |

|

Median (IQR) |

1.5 (1–2) |

1.5 (1–2) |

1.0 (1–2) |

.16 |

Self-reported actual time spent in CD role, days/week |

.15 |

<1.5 |

16 (21) |

6 (14) |

10 (30) |

|

= 1.5 |

17 (22) |

9 (21) |

8 (24) |

|

>1.5 |

43 (57) |

28 (65) |

15 (45) |

|

Median (IQR) |

2.0 (1.5–2.5) |

2.0 (1.5–3) |

1.5 (1–2) |

.04** |

Patient care time, days/week |

|

None |

5 (7) |

2 (5) |

3 (9) |

.94 |

0.5–1.5 |

28 (37) |

16 (37) |

12 (36) |

|

2–3 |

36 (47) |

21 (49) |

15 (45) |

|

≥3.5 |

7 (9) |

4 (9) |

3 (9) |

|

Median (IQR) |

2 (1–2.75) |

2 (1–2.5) |

2 (1–3) |

.97 |

Protected scholarship time, days/week |

.02** |

None |

50 (66) |

33 (77) |

17 (52) |

|

≥0.5 |

26 (34) |

10 (23) |

16 (48) |

|

Median (IQR) |

0 (0–0.5) |

0 |

0 (0–0.5) |

.03** |

PERCEPTIONS ABOUT THE CD ROLE |

Increases promotion prospects |

65 (86) |

36 (84) |

29 (88) |

.75 |

Helps attain career goals |

71 (93) |

41 (95) |

30 (91) |

.65 |

Increases compensation |

25 (33) |

14 (34) |

11 (33) |

.94 |

We found that women had served as CD for significantly fewer years than men (median 5 versus 10 y, P = 0.01; Table 3). We also found some gender differences by rank, especially when looking at the mid-career level. All mid-career men were associate professors while more than half of mid-career women were still assistant professors (P = 0.045, Fisher’s exact test; Figure 1). We found no significant gender differences regarding tenure status or process for obtaining the CD position.

All but two respondents reported having protected time for their CD role (median 1.5 days/week; Table 3), yet CDs reported needing more time to fulfill role requirements (median 2 days/week). CDs reported spending a median of 2 days in direct patient care. Regarding scholarship, only one-third of CDs reported having any protected time for scholarly activities such as research, grant writing, presentations, or publications. While women had slightly more protected time for the role than men, the self-reported actual time that women spent on the role was higher than men by one-half day per week (2.0 vs 1.5 days/week, P = 0.04; Table 3). We found no gender differences in the weekly time spent in direct patient care. However, only half as many women as men had any protected scholarship time (23% vs 48%, P = 0.02).

Based on promotion criteria at their institution, 86% of respondents believed that being a CD increased their overall prospects for promotion, and 93% believed that being a CD would help them attain their professional goals (Table 3). In contrast, only one-third believed that being a CD increased their overall compensation per time worked based on their institution’s compensation structure. We found no gender differences in these perceptions about the CD role.

Predicting Academic Promotion

Using ordinal regression modeling, we examined predictors of academic promotion. In this model, the only variable predictive of promotion was total time in the CD role (Table 4). With every additional year spent in the CD role, the odds of promotion to the next level increased by 1.21-fold when controlling for CD gender, scholarly time (half days), protected time (half days), and years since residency.

Outcome: academic rank (assistant professor, associate professor, professor) |

|

Odds ratio |

Std error |

Z |

|P|>z |

95% confidence interval |

Male |

0.957 |

.491 |

–0.09 |

.931 |

0.350–2.618 |

Years as CD |

1.209 |

.080 |

2.86 |

.004 |

1.061–1.377 |

Protected time for scholarship (half-days) |

1.161 |

.391 |

0.44 |

.657 |

0.600–2.248 |

Protected time for CD role (half-days) |

0.756 |

.128 |

–1.65 |

.100 |

0.542–1.055 |

Years since residency graduation |

1.014 |

.031 |

0.46 |

.643 |

0.955–1.078 |

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

CDs in our study believed that the role was beneficial for promotion and attaining professional goals but was undercompensated both in salary and protected time. The beliefs that the CD role increased prospects for promotion and attaining professional goals were consistent with older studies.3,4 Our multivariate analysis lent modest support to this perspective, with time in the CD role being the only independent predictor of career rank (Table 4). Notably, years in the CD role were more influential than years since residency. Despite positive perceptions about the role increasing promotion, many CDs remained unpromoted: 28% of late-career CDs and 43% of mid-career CDs were assistant professors. Only 14% of total CDs in our study had attained the rank of full professor and only 20% were tenured or on the tenure track, compared to 2004 when 20% of family medicine CDs were full professors and 33% were on the tenure track.8 This trend is reflective of a downward trend for tenure in academic medicine in general and family medicine in particular.26,27 Similarly, the number of academic family physicians at the full professor rank has decreased from 12.6% in 2004 to 10.1% in 2024.28,29

In contrast to positive views on career advancement, only one-third of respondents agreed that the CD role increased compensation. Inadequate support for the position itself and CDs’ scholarship have long been issues across all specialties.8,9 CDs in our study reported 1.5 days per week or less protected time for the role, which is similar to previous findings4 but substantially less than the 2.5 days per week recommended by ACE.5 Only 16% of CDs in our sample met or exceeded the minimum recommended protected time. At the same time, CDs provided a median of 2 full days of direct patient care per week, and only one-third had any protected time for scholarship. Limited support for the position and lack of time for scholarship, coupled with the negative perception about compensation, could help explain why nearly two-thirds of CDs were asked to take on the role rather than seeking it out. The question remains of why US CDs are not better supported with pay and protected time for the role and academic pursuits, given that high-quality clerkships are vital for recruiting medical students to the specialty of family medicine.1,2

Since 2013, more than half of family medicine CDs have been women, and the percentage of women CDs has exceeded the overall percentage of women faculty.19,20,21 Our study data showed a small decrease in women in the CD role in 2024 to 57%, essentially now at parity when compared to overall full-time family medicine faculty (56% women).30 CAFM has set goals to increase female representation among CDs beyond parity to 70% women by 2025.16 In contrast, URiM has remained low among CDs despite gains in URiM family medicine department chair representation, which rose from 9.8% in 2011 to 19.1% in 2023.19 Only 7 (9%) of our US CD sample self-identified as URiM, well below the overall percentage of URiM full-time family medicine faculty (14.1%) in 202431 and even further from matching percentages in the US population.32 CAFM has set an intermediate goal to increase URiM representation among CDs to 15% by 2025 with the important aim of having family physicians who are representative of the US population.16 However, any previous measures appear not to have generated lasting increases. Given the low numbers of URiM faculty in CD positions, qualitative methods rather than quantitative analysis would be needed to explore and understand lagging URiM representation.

A lack of understanding exists of how the CD role fits into a faculty member’s career trajectory particularly as it relates to gender. Men have been in the role twice as long as women (10 years vs 5 years). This difference could represent more women using this role as a stepping stone earlier in their careers or men remaining in the role preretirement. Also, women had significantly less protected time for scholarship than men. Reasons for the differences in scholarship time may relate to men being later in their career and/or more likely to negotiate for the time.33 At the same time, women in our sample reported the same amount of direct patient care as men but more time spent on the CD role. Possibly that extra half day per week women reported spending on the CD role may displace other activities that could increase compensation and promotability, potentially contributing to known gender gaps in pay and promotion. We did not ask specifically about the breakdown of time spent within the CD role or reasons behind time allocation, so we can only speculate on how women are spending that extra time (eg, learning the new role, creating curricular innovations, mentoring/advising medical students, taking on more administrative tasks). Qualitative inquiry could further explore career trajectories, including how early-career CDs differ from late-career CDs, as well as gender differences in role duration, time spent on the role, and protected scholarship time.

Limitations

Although this is a national study, the population of US family medicine CDs numbers only 158, so the sample size is small due to the response rate (48% of US CDs). Certain subgroups of CDs may have participated disproportionately, which could affect the findings. However, the sample is well distributed across the United States, with typical representation from public and private universities and similar proportion of universities having large and small class sizes. Further, a recent study by Kost et al indicated that respondents were representative of overall family medicine CDs in terms of location, gender, race/ethnicity, self-identified URiM, and physician status.25 With a survey study, another limitation is that all data are self-reported and subject to recall bias and social desirability. Finally, given that this is an observational survey study, we can look at only association, not causation.

Recommendations

Future research should employ qualitative methods to look more deeply into perceptions of the CD position as well as motivations for taking on and remaining in this critical role in family medicine, especially among URiM and women faculty. To recruit and retain the best and brightest, it is important to ensure that the role comes with (a) adequate protected time and staff support, (b) adequate protected scholarship time along with mentorship and resources to support CDs’ eligibility for promotion, and (c) commensurate compensation so that faculty are not penalized financially for taking on this key role.

Next Steps

We have another CERA study in progress with data on the CD role from the perspective of family medicine department chairs. That study addresses the effectiveness of their CD, the amount of dedicated staff support, and the department chairs’ perspectives on the CD role in terms of promotability, potential for advancement to a higher leadership position, and compensation.

2025 Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference (scholarly roundtable discussion), Salt Lake City, UT, May 2025.

The authors thank the 2024 CERA Survey of Clerkship Directors leaders for providing in-kind support for this project. The authors also thank Jennifer Stowe, MS, for assistance with artwork, Julie Gaines, MLIS, for assistance with the literature search, and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

References

-

-

Rabinowitz HK. The relationship between medical student career choice and a required third-year family practice clerkship. Fam Med. 1988;20(2):118–121.

-

Elnicki DM, Hemmer PA, Udden MM, et al. Does being a clerkship director benefit academic career advancement: results of a national survey.

Teach Learn Med. 2003;15(1):21–24. doi:10.1207/S15328015TLM1501_05

-

Ephgrave K, Margo KL, White C, et al. Core clerkship directors: their current resources and the rewards of the role.

Acad Med. 2010;85(4):710–715. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2cdf1

-

Morgenstern BZ, Roman BJB, DeWaay D, et al. Expectations of and for clerkship directors 2.0: a collaborative statement from the Alliance for Clinical Education.

Teach Learn Med. 2021;33(4):343–354. doi:10.1080/10401334.2021.1929997

-

Beck Dallaghan GL, Ledford CH, Ander D, et al. Evolving roles of clerkship directors: have expectations changed?

Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1). doi:10.1080/10872981.2020.1714201

-

Hoffmann-Longtin KJ, Hernandez RA. If I quit in the clinic and do nothing but teach, I’m going to be looking for a new job: an exploration of uncertainty management in medical education.

Communication Studies. 2020;71(5):724–739. doi:10.1080/10510974.2020.1819840

-

Gazewood J, Margo K, Jerpbak C, Burge S, Ballinger T, Usatine R. Predoctoral directors: who are they and what do they do in these trying times? Fam Med. 2007;39(3):171–177.

-

Margo K, Gazewood J, Jerpbak C, Burge S, Usatine R. Clerkship directors’ characteristics, scholarship, and support: a summary of published surveys from seven medical specialties.

Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):94–99. doi:10.1080/10401330902791065

-

Lautenberger DM, Dandar VM. The State of Women in Academic Medicine 2023-2024: Progressing Toward Equity. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2024.

-

Richter KP, Clark L, Wick JA, et al. Women physicians and promotion in academic medicine.

N Engl J Med. 2020;383(22):2148–2157. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1916935

-

Carr PL, Raj A, Kaplan SE, Terrin N, Breeze JL, Freund KM. Gender differences in academic medicine: retention, rank, and leadership comparisons from the National Faculty Survey.

Acad Med. 2018;93(11):1694–1699. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002146

-

Dandar VM, Lautenberger DM. Exploring Faculty Salary Equity at U.S. Medical Schools by Gender and Race/Ethnicity. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2021.

-

Ganguli I, Sheridan B, Gray J, Chernew M, Rosenthal MB, Neprash H. Physician work hours and the gender pay gap — evidence from primary care.

N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1349–1357. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa2013804

-

Chen SY, Jalal S, Ahmadi M, et al. Influences for gender disparity in academic family medicine in North American medical schools.

Cureus. 2020;12(5). doi:10.7759/cureus.8368

-

Weidner A, Elliott T, Franko J. From ADFM, AFMRD, NAPCRG, & STFM: CAFM sets goals for diversity of leaders & faculty.

Ann Fam Med. 2022;20(1):95–98. doi:10.1370/afm.2784

-

Adetoye M, Gold K. Race and gender disparities among leadership in academic family medicine.

J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(5):902–905. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2022.AP.220122

-

Samuel A, Soh MY, Durning SJ, Cervero RM, Chen HC. Parity representation in leadership positions in academic medicine: a decade of persistent under-representation of women and Asian faculty.

BMJ Lead. 2023;7:1–7. doi:10.1136/leader-2023-000804

-

Ringwald BA, Edwards Y, Vengal S, Montemayor J, Ringwald C. The changing faces of academic family medicine leadership: a CERA secondary analysis.

Fam Med. 2025;57(3):201–207. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2025.804452

-

-

-

-

-

Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW. Creating a centralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research.

Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257–260. doi:10.1370/afm.2228

-

Kost A, Ellenbogen R, Biggs R, Paladine HL. Methodology, respondents, and past topics for 2024 CERA clerkship director survey.

PRiMER. 2025;9:7. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2025.677955

-

Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Syed ZA, Shakil A, Schneider FD. Trends in tenure status in academic family medicine, 1977–2017: implications for recruitment, retention, and the academic mission.

Acad Med. 2020;95(2):241–247. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002890

-

Mallon WT, Cox N. Promotion and tenure policies and practices at U.S. Medical schools: is tenure irrelevant or more relevant than ever?

Acad Med. 2024;99(7):724–732. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000005689

-

-

-

-

-

-

Stead W, Manne-Goehler J, Blackshear L, et al. Wondering if I’d get there quicker if I was a man: factors contributing to delayed academic advancement of women in infectious diseases.

Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10(1). doi:10.1093/ofid/ofac660

There are no comments for this article.