Background and Objectives: Maternal care in the United States is in crisis due to obstetrics workforce shortages. Family physicians, with whole-person training and geographical practice distribution, are well-positioned to address this crisis. Family physicians completing a family medicine obstetrics (FMOB) fellowship are trained in surgical skills and high-risk pregnancy management, and often practice in health care shortage areas. This study aimed to update and expand knowledge on FMOB fellowships, focusing on program characteristics and financial sustainability.

Methods: We sent an email-based survey examining fellowship structure and financial information to 44 FMOB fellowships. Representatives of 22 fellowships (50%) anonymously completed the online survey. Authors used descriptive statistics, including frequency, mean, and standard deviation, to summarize the data.

Results: Half the fellowships were housed in family medicine residency programs. Fellowships, mostly 1 year long, admitted on average 2.2 fellows annually. Financially, nearly half (45%) the fellowships operated at a budget deficit, with clinical revenue and federal funding being major funding sources. More than 50% of programs reported that fellows spent less than 20% of their time as an independent billing physician.

Conclusions: FMOB fellows are surgically trained and uniquely positioned to help address the current crisis, including filling obstetric care gaps in underserved and rural areas. Given funding challenges FMOB fellowships face, developing strategies for financial viability of FMOB fellowships going forward is crucial. Opportunities include increasing clinical revenue generation and attaining secure funding via pursuit of accreditation status for FMOB fellowship programs from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Maternal care in the United States is in crisis, largely related to shortages in the obstetrics workforce. The United States has the highest rates of pregnancy-related mortality among high-income nations,1 with rates having tripled since 1987.2,3 Recent evidence demonstrated that maternal mortality was nearly twice as high in rural areas4 and underserved populations, including non-Hispanic Black patients2 and individuals identifying as American Indian/Alaskan native.5 Furthermore, mental health is the leading cause of maternal mortality in the United States, with more than 20% of deaths related to concerns such as suicide, substance use, or overdose.6 Inequity in access to maternal health care, including concentration of obstetricians and maternal-fetal medicine specialists in urban and academic hospital settings, plays a significant role in poor outcomes.7 Addressing this care gap is critical given that more than half of US counties do not have hospitals with obstetric care, and 35% are maternity care deserts.8 Evidence has suggested that when care is not available locally, increased travel time and burden contribute to poor health outcomes.9,10

Family medicine providers represent a substantial component of the obstetrics workforce and based on their training and scope of practice are uniquely suited to help address the maternal care crisis in the United States.11 Family medicine residents are trained to care for pregnant patients in outpatient and inpatient settings, and may seek comprehensive maternal care training during residency, further preparing them to integrate obstetrics into independent practice.12 Twenty-seven percent of recent family medicine graduates go on to provide some maternal care,13 and approximately 6.7% of established family physicians provide obstetric care in their practice.14 Given the more than 120,000 practicing family physicians, these percentages translate to approximately 8,400 family physicians providing deliveries, with family physicians making up approximately 16% of the obstetrics workforce (based on approximately 43,000 OB/GYNs practicing in the United States).15 Family physicians are more likely than any other primary care physician specialty to practice in rural or underserved areas,16 with 27.9% of recent graduates practicing in medically underserved areas.17 Family physicians in rural areas are more likely to deliver babies than family physicians in urban areas.8 Importantly, family physicians are uniquely able to care for both physical and mental health needs beyond the postpartum period; this extended duration is critical because more than half of pregnancy-related deaths occur between 7 and 365 days after birth.18 The ability of family physicians to care for broader populations (ie, all ages and genders) with diverse needs, joined with the ability to provide comprehensive pregnancy-related care, make them particularly well-suited for meeting obstetrics workforce needs.

Supporting advanced training for family physicians in maternal care is essential to addressing the obstetrics health care gap, particularly in underserved areas. Family physicians may receive postresidency specialized training in obstetric care through a 12 month, full-time family medicine obstetrics (FMOB) fellowship. Fellowship training often includes cesarean surgical skills, high-risk pregnancy management, and training for complicated vaginal deliveries. FMOB fellowships play an essential role in addressing the maternal health care crisis because most graduates go on to provide surgical care in community-based hospitals19 and more than half of graduates practice in rural areas.14,20,21 Additionally, among family physicians who perform cesarean deliveries, more than 38% provide care to patients living in counties with no OB/GYN physicians.14

Understanding the current state of FMOB fellowships in the United States is critical given the maternal health care needs in rural and underserved areas. However, because FMOB fellowships lack accreditation from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), gathering this information is challenging. No data on these fellowships are regularly collected, curriculum requirements are not standardized, and programs’ websites tend to provide insufficient information to understand the fellowships’ operational structure.22 Whereas career choices of FMOB graduates have been examined, less is known about characteristics of the fellowship programs themselves. We found one widely implemented survey of FMOB fellowships, conducted in the United States in 2014, that summarized program characteristics and affiliations, education and training curricula, and outcomes of fellows, including cesarean privileges and practice locations.21 That survey demonstrated strong curricula across programs and a desire for formalized accreditation; however, that survey did not address fellowship funding, an important consideration for continuation of these fellowships.

To further support, sustain, and expand FMOB fellowships, an in-depth understanding of current program characteristics, including funding strategies, is needed. Our study sought to update and expand knowledge regarding FMOB fellowships. In addition to understanding program characteristics, affiliations, and settings of care, our study uniquely sought to understand financial and funding characteristics of FMOB fellowships. An updated, comprehensive view of FMOB fellowships will shed light on facilitators and barriers to maintaining and further expanding them to meet current maternal health care needs.

From the American Association of Family Physicians fellowship directory, we identified 49 fellowships focused on advanced maternal care and obstetrics for family physicians. We obtained valid email addresses for 44 of the fellowships. We sent email invitations with survey links to fellowship representatives and administered the survey using the Qualtrics XM platform. The survey was open from February 20, 2024 to April 20, 2024, with multiple reminders sent to fellowship representatives who had not completed the survey. Responses were anonymous. Representatives of 22 fellowships (50%) completed surveys online; 21 of those providing responses identified as the fellowship director, and one identified as program coordinator.

Faculty and research staff at the University of Utah Department of Family and Preventive Medicine designed the survey. The survey included items on fellowship structure and financial information. Fellowship structure items included institutional home, or the fellowship’s primary organizational or administrative home, and affiliations. Respondents could choose only one option for institutional home but could select all that apply for affiliations. Structural items also included program enrollment and length, patient population, and delivery volume. Financial information items addressed fellowship operating budget, fellow salary, benefits, malpractice insurance, productivity benchmarks, funding streams, patient insurance, time fellows spend as independent billing physicians (attendings), and settings in which fellows work as attendings. We used descriptive statistics, including frequencies, averages, and standard deviations, to summarize responses.

Fellowship Structure

Half (50.0%, n = 11) of fellowship programs were primarily housed in family medicine residency programs; 4 (18.2%) were based in community hospitals; and 3 (13.6%) were attached to academic medical centers. The other programs were housed in academic medical centers, federally qualified health centers (FQHC), or in other organizations.

Many fellowship programs were affiliated with residencies (n = 15, 68.2%), community-based hospitals (n = 14, 63.6%), and academic medical centers (n = 10, 45.5%). Fewer programs were affiliated with FQHCs or other organizations. Programs reported admitting an average of 2.2±1.2 fellows annually; specifically, programs admitted 1 (n = 8. 36.4%), 2 (n = 7, 31.8%), 3 (n = 2, 9.1%), or four or more (n = 5, 22.7%) fellows. The majority (n = 20, 90.9%) of programs were 1 year in length.

More than half of fellowship programs (n = 12, 54.5%) primarily served a mix of urban, urban-low income, suburban, and rural patients. Six (27.3%) programs exclusively served an urban low-income patient population. No programs reported exclusively serving rural patients.

Respondents estimated that fellows performed approximately18 vaginal and 14±7.2 caesarean deliveries per month. Roughly half of the vaginal deliveries were performed as trainees (9.4±6.8) and half as attendings (8.9±14.2). Fellows performed few vacuum- or forceps-assisted vaginal deliveries as trainees or attendings. For additional detail on fellowship structure, see Table 1.

Survey measures and response options |

n (%) |

Institutional home (N = 22) |

Family medicine residency program |

11 (50.0) |

Community-based hospital |

4 (18.2) |

Attached to an academic medical center |

3 (13.6) |

Academic medical center |

1 (4.5) |

Federally qualified health center (FQHC) or lookalike |

1 (4.5) |

Other |

2 (9.1) |

Affiliations (N = 22) |

Family medicine residency program |

15 (68.2) |

Community-based hospital |

14 (63.6) |

Academic medical center |

10 (45.5) |

FQHC (or lookalike) |

4 (18.2) |

Other |

1 (4.5) |

Annual admission (N = 22) |

Average, mean (SD) |

2.2 (1.2) |

1 |

8 (36.4) |

2 |

7 (31.8) |

3 |

2 (9.1) |

4+ |

5 (22.7) |

Fellowship length (N = 22) |

1 year |

20 (90.9) |

2 years |

2 (9.1) |

Patient population (N = 22) |

Mixed |

12 (54.5) |

Urban—low income |

6 (27.3) |

Urban |

3 (13.6) |

Suburban |

1 (4.5) |

Rural |

0 |

Deliveries performed (monthly), mean (SD) |

Spontaneous vaginal, trainee (n = 20) |

9.4 (6.8) |

Spontaneous vaginal, attending (n = 14) |

8.9 (14.2) |

Vacuum assisted, trainee (n = 21) |

1.1 (0.9) |

Vacuum assisted, attending (n = 11) |

0.5 (0.7) |

Forceps assisted, trainee (n = 21) |

0.6 (0) |

Forceps assisted, attending (n = 11) |

0 |

Caesarean, trainee (n = 21) |

14 (7.2) |

Fellowship Financial Information

Nearly half of fellowship programs operated with a budget deficit. Specifically, 9 (45.0%) programs operated with a budget deficit, 8 (40.0%) operated with a balanced budget, and 3 (15.0%) operated with a budget surplus.

Fellow salary and provision of malpractice coverage are significant costs of running an FMOB fellowship program. Seven (33.3%) fellowships reported salaries from $60,000 to $69,999, and 7 (33.3%) from $70,000 to $79,999. Additionally, 6 (28.5%) reported salaries greater than $80,000, and 1 (4.8%) program reported salaries in the range of $50,000 to $59,999. Most programs (n = 15, 71.4%) were self-insured for malpractice through a medical system or university. Three (14.3%) obtained malpractice coverage through the Federal Tort Claims Act, and 2 (9.5%) through private insurance. See Table 2 for additional details on operating budget, fellow salary, and malpractice coverage.

|

Survey measures and response options

|

n (%)

|

|

Operating budget (N = 20)

|

|

A budget deficit

|

9 (45.0)

|

|

A budget surplus

|

3 (15.0)

|

|

A balanced budget

|

8 (40.0)

|

|

Fellow salary (N = 21)

|

|

$ 50,000–$ 59,999

|

1 (4.8)

|

|

$ 60,000–$ 69,999

|

7 (33.3)

|

|

$ 70,000–$ 79,999

|

7 (33.3)

|

|

$ 80,000–$ 89,999

|

4 (19.0)

|

|

$ 90,000 or more

|

2 (9.5)

|

|

Cost of benefits (N = 21)

|

|

20% or less of fellow salary

|

7 (33.3)

|

|

21%–25% of fellow salary

|

1 (4.8)

|

|

26%–30% of fellow salary

|

2 (9.5)

|

|

31%–35% of fellow salary

|

3 (14.3)

|

|

I’m not sure

|

8 (38.1)

|

|

Malpractice insurance (N = 21)

|

|

Self-insured

|

15 (71.4)

|

|

Federal tort claims act

|

3 (14.3)

|

|

Private insurance

|

2 (9.5)

|

|

Other (please specify)

|

0

|

|

I’m not sure

|

1 (4.8)

|

|

Productivity benchmarks (N = 22)

|

|

Patient encounter benchmarks

|

4 (18.2)

|

|

Relative value unit (RVU) benchmarks

|

1 (4.5)

|

|

Templates

|

2 (9.1)

|

|

Other benchmarks

|

3 (13.6)

|

|

No productivity benchmarks

|

16 (72.7)

|

|

Time spent as attending, independent billing physician (n = 21)

|

|

Less than 20%

|

12 (57.1)

|

|

20%–29%

|

2 (9.5)

|

|

30%–39%

|

0

|

|

40%–49%

|

1 (4.8)

|

|

50%–59%

|

3 (14.3)

|

|

60% or more

|

3 (14.3)

|

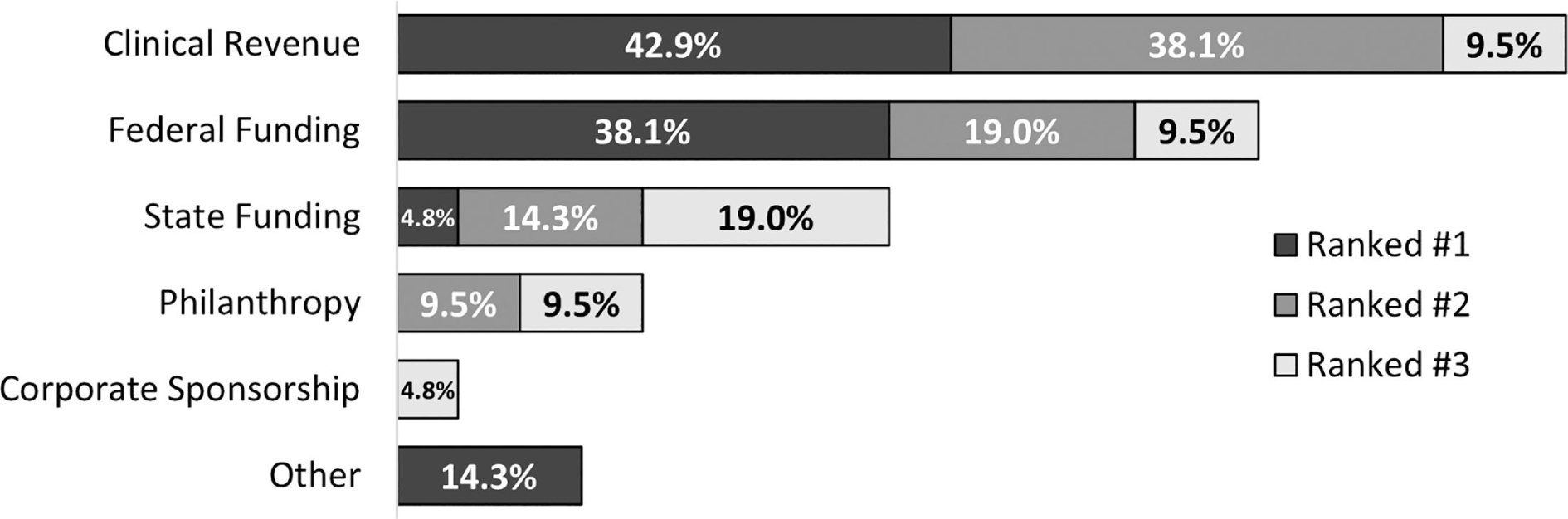

Respondents indicated that clinical revenue and federal and state funding were the major sources of funding (Figure 1). The highest ranked funding stream was clinical revenue; 19 (90.5%) programs ranked clinical revenue in their top three funding sources, and 9 (42.9%) ranked it number one. The next highest ranked funding stream was federal funding; 14 (66.7%) ranked it in the top three, and 8 (38.1%) ranked it number one. Eight (38.1%) programs ranked state funding in their top three, and 4 (19.0%) ranked philanthropy in their top three. One (4.8%) program ranked corporate sponsorship as their third largest funding stream. Three programs ranked other funding sources as their number one. Other funding streams included internal funding through hospital or medical group (two programs) and funding shared with a family medicine residency (one program).

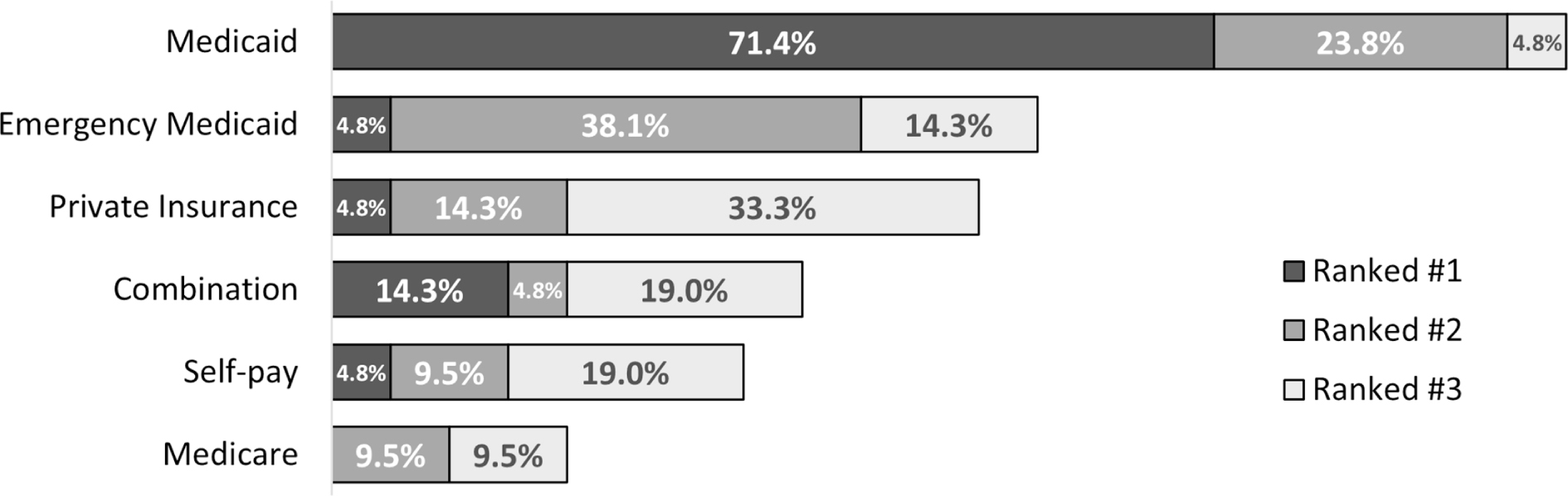

Medicaid was the most common type of patient insurance coverage; all 21 programs included Medicaid in their top three most common patient insurance types, and 15 (71.4%) ranked it number one (Figure 2). Other common insurance types included Emergency Medicaid and private (ie, commercial) insurance; 12 (57.1%) and 11 (52.4%) programs ranked these insurances in their top three most common, respectively. Eight programs (38.1%) ranked combinations of public and private insurance and self-pay in the top three most common patient coverage types; 3 (14.3%) programs ranked it number one. Exclusively self-pay (n = 7, 33.3%) and exclusively Medicare (n = 4, 19.0%) were less commonly included in the top three.

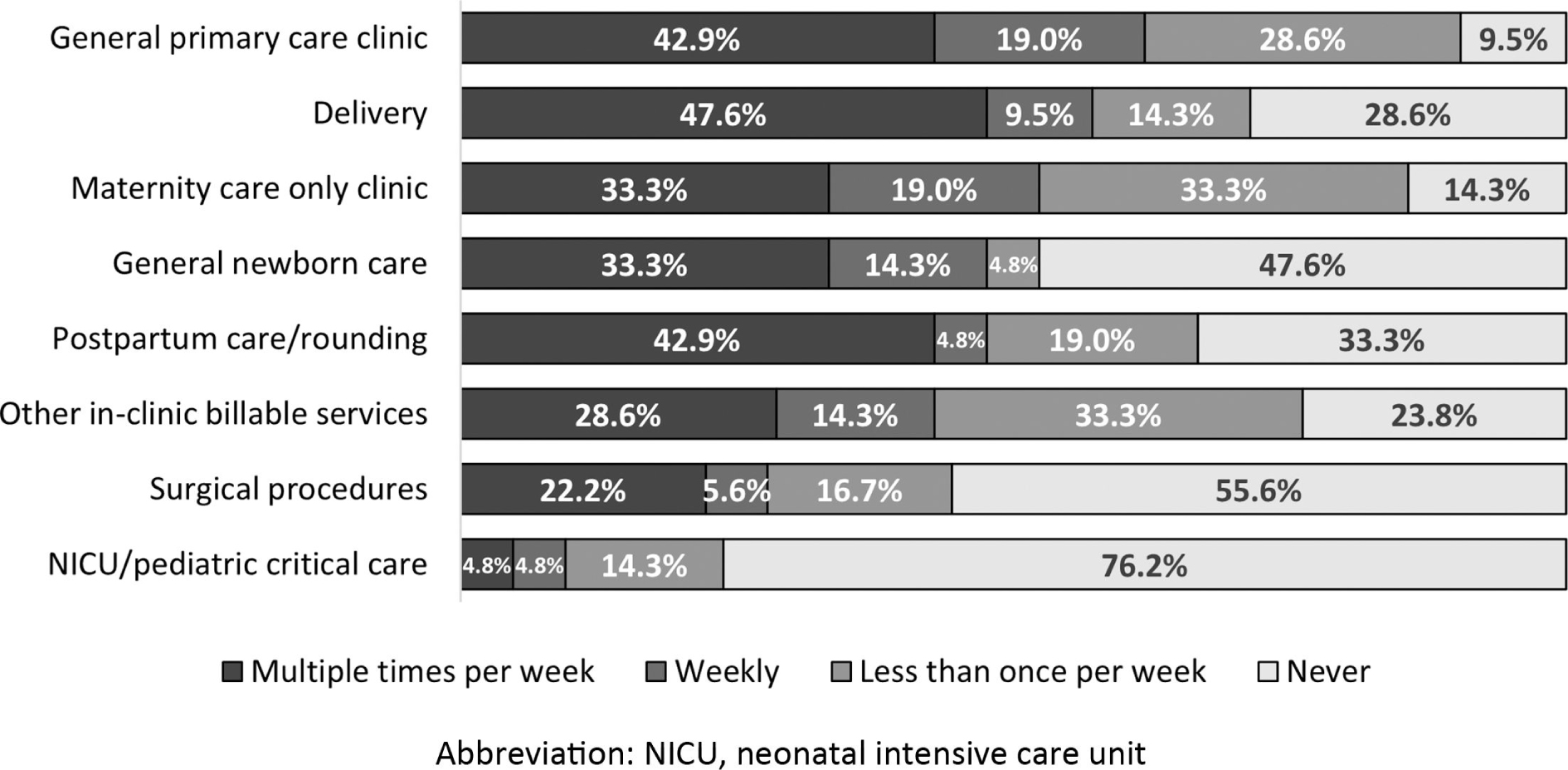

Most (n = 16, 72.7%) fellowship programs reported that they do not use productivity benchmarks for fellows working as attendings. Of programs that used benchmarks, 4 (18.2%) used patient encounters, 2 (9.1%) used templates, 1 (4.5%) used relative value units (RVUs), and 3 (13.6%) used other benchmarks. More than half of programs reported that fellows spend less than 20% of their time as billing physicians or attendings (Figure 3). Common settings in which fellows work as attendings at least weekly include general primary care clinics (n = 13, 61.9%), labor and delivery (n = 12, 57.1%), and maternal care only clinics (n = 11, 52.3%).

This study sought to update and expand the available knowledge regarding FMOB fellowships. Since the identification of 29 active programs in 2014,21 the number has grown to include 44 verifiable FMOB fellowship programs.22 Our findings suggest that structure and many characteristics of FMOB fellowships have remained fairly consistent over the last decade. Most programs remain affiliated with resident training programs and community- and university-based hospitals. The majority of programs admit an average of two fellows and remain 1 year long.

Our study expands on prior research to examine the financial structure and funding of these programs. Of note, nearly half of programs reported operating with a budget deficit. Sustainability of FMOB fellowship programs is critical given the potential of graduates to fill the gap in maternity health care. With programs graduating an average of just over two fellows each year, nearly 100 new surgically trained fellows will enter the workforce annually. Furthermore, if current trends continue,14,20,21 approximately half of graduating fellows will work in rural or otherwise underserved regions, increasing access to crucial prenatal, obstetrical, and postpartum services for many patients.

Our data suggest that funding is an area of concern for many fellowship programs. Ninety percent of programs ranked clinical revenue in the top three funding sources, and clinical revenue was the number one funding stream for more than 40% of programs. Next, we consider clinical revenue implications of fellows as attendings and the use of productivity benchmarks.

The time that fellows work as attending physicians or in independent practice profoundly impacts clinical revenue. In independent practice, fellows perform and bill for services in their core specialty, family medicine. More than two-thirds of fellowship programs reported that fellows spend less than half of a typical work week in an attending role. More than half of programs reported that fellows work as attendings less than 20% of a typical work week. As unaccredited programs, FMOB fellowships may be able to enhance sustainability by increasing fellows’ time spent as independent practicing physicians, thereby increasing revenue. Having fellows primarily perform vaginal deliveries in the attending role can increase clinical revenue and enable supervisory faculty to perform other revenue-generating clinical work. Alternatively, if ACGME accredits FMOB fellowships, use of graduate medical education (GME) funds may supplement funding, reducing the need for revenue from fellow independent billing. ACGME common program requirements for fellowships limit the time fellows may engage in independent practice of their core specialty to 20% or less of their time per week, or 10 weeks of an academic year.23

Additional research is needed to identify the specific reasons FMOB fellows do not spend more time as billing physicians. Some potential reasons are administrative, program priorities, or factors related to liability or revenue. Particularly with unaccredited programs, a patchwork of state and federal laws and insurance and institutional policies govern fellow billing practices, which may encourage programs to limit fellow billing to avoid potential compliance issues. In addition, the process of credentialing new physicians with hospitals and insurance carriers can be onerous compared to the short-term billing benefits. FMOB fellowships consider training as fundamental and may prioritize training and clinical experience over fellows’ billing. Although licensed and credentialed, fellows are in a training role; some fellowships may choose not to have fellows bill because of liability and malpractice factors. Lastly, experienced physicians may bill more efficiently. Fellowships may seek to maximize revenue by minimizing billing by fellows and maximizing billing by more experienced attendings.

Nearly three-quarters of fellowship programs did not use productivity benchmarks for fellows functioning as independent billing physicians in outpatient clinics. Among programs that used benchmarks, patient visit numbers were the most frequent metric. Only one program used RVU benchmarks. Patient visit benchmarks focus on patient volume, but do not address the value of services and the complexities of reimbursement. RVU benchmarks, in contrast, are directly tied to the value of services and translate more directly to revenue. Given the importance of clinical revenue as a funding stream, increasing the use of benchmarks, particularly RVUs, has potential to improve funding and sustainability for fellowship programs.

In addition to clinical revenue, federal funding was an important source of funding for fellowship programs. Two-thirds of programs ranked federal funds in their top three funding sources, and federal funds were the primary source for nearly 40%. The reliance on federal funding is noteworthy given its temporary nature and the potential for nonrenewal of grants, creating financial insecurity. In contrast, GME funds have historically been a stable, long-term source of federal funds. ACGME accreditation would enable FMOB fellowship programs to qualify for GME funding. One survey suggested that the majority of FMOB fellowship directors and other stakeholders, including current and recent fellows, support the idea of ACGME accreditation;24 however, this formalization could present challenges such as loss of curricular flexibility. Concerns also were raised about the potential negative impact on nonfellowship trained family physicians already providing full-spectrum obstetric care, particularly if a certificate of added qualification (CAQ) becomes considered essential to obtaining hospital privileges.24 The balance of more stable funding streams must be weighed against changes in flexibility, administrative burden, and other unintended consequences.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study had several limitations that must be acknowledged. All data were self-reported, and thus were subject to recall bias. Respondents may have had varying levels of familiarity with financial information; for example, more than 30% of respondents were unaware of the costs of fellows’ benefits. Interestingly, this finding itself may be noteworthy given the importance of financial sustainability. Additionally, because surveys were anonymous, we cannot know whether results generalize to programs that did not respond; however, similarity of program structure to that found in prior research21 supports the likelihood of generalizability. Our response rate was approximately 50%; while this is a typical response rate for a sample of physician specialists,25 we cannot know whether all programs would have responded similarly. Strengths of this study included relatively high completion rate of participants from nationwide programs and the comprehensive scope of the survey questions.

Despite increasing numbers of FMOB fellowships, the long-term funding of many of these programs is challenged by budgets operating in deficit. Although programs can focus on increasing clinical revenue for internal funding, an increase in consistent governmental funding would improve sustainability to ensure the ability of these programs to continue to graduate FMOB surgically trained physicians. Without ACGME accreditation, FMOB programs currently are not eligible for federal GME funding. The complicated question of benefits versus potential negative consequences of pursuing accreditation is one that remains to be explored.

FMOB fellowship trained physicians serve an essential role in addressing the maternal care crisis in the United States, especially in rural and underserved areas. Family physicians’ training encompasses care of the parent-child dyad for the first year of life and beyond; pregnancy outcomes and delivery complications are comparable between family physicians and OB/GYNs.26 Furthermore, family physicians are well-equipped to address mental health concerns, which is critical given that factors related to mental health (ie, suicide and substance use overdose) are the leading cause of maternal mortality.6 FMOB trained physicians are practicing in rural areas, have skills in surgery and high-risk pregnancies, and can fill their practice providing care for the entire population. To better address care and access needs, FMOB fellowships need to be expanded, which is dependent on developing long-term financial sustainability.

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) provided support for this study as part of a primary care training and enhancement award (T34HP42133). The contents of this study are of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by HRSA, HHS or the US Government. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Utah reviewed and exempted this study (IRB_00173315).

Presented at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference, May 5, 2025, Salt Lake City, UT.

References

-

-

-

-

Harrington KA, Cameron NA, Culler K, Grobman WA, Khan SS. Rural–urban disparities in adverse maternal outcomes in the United States, 2016–2019.

Am J Public Health. 2023;113(2):224–227. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2022.307134

-

Trost S, Beauregard J, Chandra G, et al. Pregnancy-related deaths among American Indian or Alaska Native persons: Data from maternal mortality review committees in 36 US States, 2017–2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022.

-

-

Deutchman M, Macaluso F, Bray E, et al. The impact of family physicians in rural maternity care.

Birth. 2022;49(2):220–232. doi:10.1111/birt.12591

-

-

Sugg M, Shakya S, Ulrich S, Tyson JS, Runkle J. Mapping maternity care deserts: Driving distance and health outcomes in North Carolina.

J Rural Health. 2025;41(2). doi:10.1111/jrh.70020

-

Deng S, Chen Y, Bennett KJ. The association of travel burden with prenatal care utilization, what happens after provider-selection.

BMC Health Serv Res. 2024;24(1):781. doi:10.1186/s12913-024-11249-9

-

Spiess S, Owens R, Charron E, et al. The role of family medicine in addressing the maternal health crisis in the united States.

J Prim Care Community Health. 2024;15. doi:10.1177/21501319241274308

-

-

-

Tong ST, Eden AR, Morgan ZJ, Bazemore AW, Peterson LE. The essential role of family physicians in providing cesarean sections in rural communities.

J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(1):10–11. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2021.01.200132

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Owens R, Whittaker TC, Galt A, et al. Assessment of family medicine obstetrics fellowship websites in the United States: Content and Usability.

J Prim Care Community Health. 2024;15. doi:10.1177/21501319231225365

-

-

-

Cunningham CT, Quan H, Hemmelgarn B, et al. Exploring physician specialist response rates to web-based surveys.

BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15(1):32. doi:10.1186/s12874-015-0016-z

-

Avery DM, Graettinger KR, Waits S, Parton JM. Comparison of delivery procedure rates among obstetrician-gynecologists and family physicians practicing obstetrics. Am J Clinical Med. 2014;10(1):16–20.

There are no comments for this article.