Nepal, a low-middle income, land-locked country in Southeast Asia sandwiched between China and India and home of eight of the 10 highest mountains in the world, was relatively isolated until the 1980s. Nearly 80% of the population of approximately 31 million still reside in rural areas with rugged terrain, making access to health care challenging for many.1 Nepal has had dramatic changes in both the government and the health care sector since the article published in Family Medicine in 2000 (Table 1). 2

SPECIAL ARTICLES

Progress and Challenges in Family Medicine and Residency Training Over 25 Years in Nepal

Tula Krishna Gupta, MD | Lani Kay Ackerman, MD

Fam Med. 2025;57(5):328-332.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2025.591411

Over the past 25 years, Nepal has made admirable progress not only in improving living conditions and health indices but also in training family physicians, called medical doctors in general practice (MDGPs). This article examines the evolution and contributions of family physicians, the development of their own unique residency curriculum, and their current and evolving practice scope. It also evaluates recruitment and retention challenges and suggests strategies for advancing family medicine in Nepal. Family physicians have been pioneers in health care delivery in Nepal and have had a profound impact on improving access to primary and emergent medical care for the rural population. They have contributed to the decrease in morbidity and mortality rates and improved life expectancy. Family medicine residencies and physicians have been and are evolving to meet the ever-changing needs of their country, leading primary and emergency care; but urgent reforms are needed for their recruitment and retention. Despite Nepal’s uniqueness and leadership in South Asia in its recognition for and development of full-scope, well-trained family physicians, MDGP leaders need collaboration and support from both their own government and medical community, as well as from international educators, to continue to lead the country in improving health and decreasing health disparities.

|

Date |

Key event impacting family medicine development |

|

1964 |

—Nepal Medical Council formed by the government of Nepal to oversee registration of qualified doctors (and later to accredit medical colleges and residencies) |

|

1978 |

—First medical college opens at Tribhuvan University, Institute of Medicine for MBBS —Kathmandu Primary health system established with health posts at the village level |

|

1982 |

—Calgary Nepal Project funded by government of Nepal and University of Calgary, Canada, launches the first postgraduate training in Nepal, MDGP |

|

1990 |

—Multiparty democracy within a constitutional monarchy established in Nepal |

|

1990 |

—GPAN established as a chapter of the Nepal Medical Association —GPAN starts and MDGP Journal begins publishing |

|

1991 |

—MDGP program shifts from Canada and Nepal to only Nepal Entrance exam required |

|

1993 |

—National Safe Motherhood Program begins operating in 10 districts |

|

1996–2006 |

— Maoist-led civil war disrupts primary health care in rural areas and impacts MDGP physicians and all health workers, particularly in rural areas |

|

2001 |

—National Academy of Medical Sciences opens —Royal family massacre impacts stability of government and health system —BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences begins family medicine/MDGP residency |

|

2005 |

—Patan Hospital begins MDGP residency |

|

2006 |

—Nepal Medical Council develops regulations for postgraduate practice |

|

2008 |

—240-year Shah dynasty abolished, and federal democratic republic established |

|

2010 |

—Journal of General Practice and Emergency Medicine of Nepal started by GPAN —Family medicine incorporates emergency medicine as well |

|

2015 |

—New constitution restructures the political system into a federal republic and declares that health is a fundamental human right —Restructure of health system with more local government autonomy and creation of seven new provinces, impacting distribution of funds and family doctors |

|

2015 |

—Massive earthquakes disrupt health care, especially in rural areas, impacting MDGP physicians and further increasing rural/urban inequity of services |

|

2016–current |

—Federal system with mixed health care financing system with theoretically free basic services and health insurance Targeted social health protection initiated |

|

2023 |

—General Practice Association of Nepal (GPAN) renamed General Practice Emergency Medicine Association of Nepal (GPEMAN) |

Abbreviations: MDGP, medical doctor in general practice; MBBS, bachelor of medicine and bachelor of surgery; GPAN, General Practitioner Association of Nepal

Though Nepal has made great progress in increasing life expectancy (from 57 to 73), reducing maternal mortality (from 539 to 151 per 100,000), infant mortality (from 78 to 28), and neonatal mortality (from 50 to 21),6-9 large disparities still exist among different regions and social groups in access to and quality of health care. Health services in urban areas are estimated at 25 times that of rural regions, and maternal and neonatal mortality rates are 3 to 5 times higher in remote, rural areas compared to metropolitan areas. 4, 6, 7, 10

Family Medicine Development in Nepal and Contributions of MDGPs

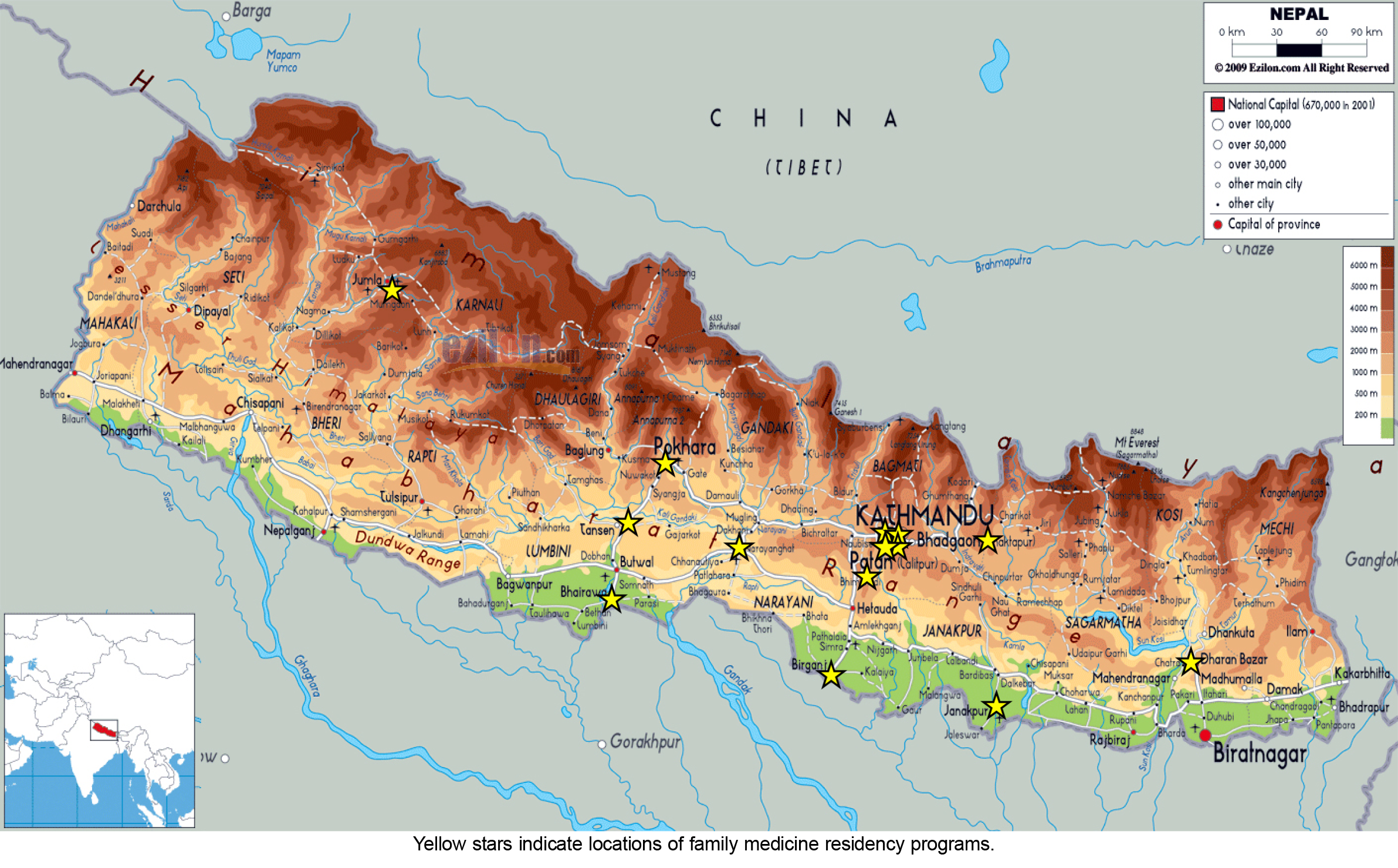

Formal medical education in Nepal began in 1978 when the Institute of Medicine (IOM) at Tribhuvan University in Kathmandu became the first medical college granting a bachelor of medicine and bachelor of surgery (MBBS) degree, equivalent to the MD degree in the United States. In 1982, a collaboration between IOM, Tribhuvan University, and University of Calgary (Canada)—the Calgary Nepal Project—launched the first postgraduate training in Nepal. This family medicine residency, which referred to its graduates as medical doctors in general practice (MDGPs), was the first 3-year residency in family medicine in Southeast Asia, and became not only the forerunner of other specialties but also the foundation for primary care.2, 11, 12, 13 Shortly after, a proliferation of public and private medical colleges and residencies ensued to a total of 22, with the Nepal Medical Council overseeing the registration and later accreditation of the programs (Figure 1). 11

From the inception of primary health care in Nepal, the contributions of family physicians have aligned with the needs of their country. A 5-year study demonstrated that family physicians with advanced obstetric and surgical skills decreased mortality and morbidity, resulting in a call from the community for more such physicians.14 In a rural, resource-limited hospital serving multiple districts, retrospective review of procedural volume after addition of family physicians showed the following new services: cesarean delivery, appendectomy, hernia and hydrocele repair, orthopedic surgery, tubal ligation and vasectomy, chest tube insertion, continuing medical education for all staff, rotations for MDGP residents, increase in access to care in all areas in the region, and improved health care indices.15 By providing comprehensive advanced obstetrical and emergency care at rural hospitals, institutional birth rates increased, with a subsequent decrease in infant and maternal mortality.16 Another 5-year study showed increased utilization of health care in the community after arrival of a family physician providing primary care and surgical services.17 In Karnali province, one of the most inaccessible and underserved regions in Nepal, family physicians successfully implemented emergency obstetric care, reducing maternal and neonatal mortality rates. 18

Though the primary health care system in Nepal has been active since 1978,5, 12 rural family doctors have strengthened the system by providing accessible health care, directing vaccination campaigns, supporting mid- and low-level health care providers, developing referral systems, working with the public health system, and leading change.13 The massive 2015 earthquake, followed by the COVID-19 pandemic, exposed the lack of resources within the infrastructure of Nepal’s four-tier primary health care system of community health workers, primary health centers, secondary-level health care facilities (district hospitals), and tertiary health care facilities (specialized hospitals)19 and highlighted the family physicians’ critical role as the backbone of the primary health care system.

With chronic diseases now superseding infectious diseases in causes of disability and death, family physicians have taken the lead in providing care for mental illness,20 chronic disease management,21, 22 and even cancer.23 Family physicians effectively triage patients in both the emergency department and outpatient clinics,24 improving the health system efficiency. They are conducting needed clinical research on local disease patterns and outcomes.25, 26 In addition, family/MDGP physicians have led the field of emergency medicine and recently started emergency medicine fellowships for MDGP graduates. As faculty in medical colleges, family physicians are the leaders in teaching students emergency medicine, clinical medicine, humanities, and ethics. 27, 28

Family Medicine Postgraduate (Residency) Development and Scope of Practice

While family medicine residencies are based at teaching hospitals and clinics, many rotations are at rural district hospitals. The previous apprenticeship-based program (with a timeline governed by the Nepal Medical Council) is now changing to competency-based residency education.29 The family medicine residency follows a structured 3-year curriculum similar among most institutions (Table 2).

|

|

Posting department |

Weeks |

|

First-year rotations |

||

|

1 |

Orientation and training |

1 |

|

2 |

Internal medicine |

18 |

|

3 |

Dermatology |

4 |

|

4 |

Pediatrics |

18 |

|

5 |

Psychiatry |

4 |

|

6 |

Forensic medicine |

2 |

|

7 |

General practice and emergency with radiology |

4 |

|

8 |

Examination |

1 |

|

Second-year rotations |

||

|

1 |

Orientation and training |

1 |

|

2 |

Surgery |

18 |

|

3 |

Anesthesiology |

4 |

|

4 |

Obstetrics and gynecology |

18 |

|

5 |

Orthopedics |

6 |

|

6 |

General practice and emergency |

4 |

|

7 |

Examination |

1 |

|

Third-year rotations |

||

|

1 |

Orientation and training |

1 |

|

2 |

District hospital posting |

18 |

|

3 |

Anesthesia and intensive care unit |

5 |

|

4 |

Emergency |

18 |

|

5 |

Radiology |

4 |

|

6 |

Elective |

4 |

|

7 |

Examination |

2 |

Note: Admission requirement includes completion of Grade 12 and MBBS degree (MD equivalent) from a college approved by the Nepal Medical Council, and satisfactory score on the entrance exam.

Abbreviations: MDGP, medical doctor in general practice; MBBS, bachelor of medicine and bachelor of surgery

Unique aspects of the Nepali family medicine curriculum, compared to that of the United States and many other countries, include a dual emphasis on pediatrics and adult medicine, a mandatory forensic medicine rotation, extensive emergency medicine training, increased surgical and obstetrical training, a hospital-based focus, and an emphasis on development of team management and leadership skills.18 Training in community-based continuity care, epidemiology, primary care, preventive medicine, and health promotion is also a unique aspect of the family medicine curriculum. Most programs have a family medicine outpatient clinic and observation beds in the emergency department; however, while the residents manage the hospital patients on the services on which they rotate, not all teaching hospitals have a separate inpatient ward. Family medicine/MDGP residents spend months in community and rural rotations as well, where they are supervised by other family physicians in inpatient and outpatient settings. Teaching, evaluation, and assessment of residents are done by MDGP faculty physicians through direct observation as well as with input from specialty faculty with whom the residents rotate. In addition, objective structured clinical examinations, logbook reviews, case-based evaluations, and external examiners (MDGP or family physicians from other institutions) are used for assessment and advancement. Core competencies of patient-centered care, clinical reasoning, procedural skills, communication skills, scholarship, leadership, community orientation, and professionalism are evaluated.29 Upon successful completion of the program and passing the required exams, graduates earn an MD degree in general practice (MDGP; similar to a US board certification in family medicine*).

Family/MDGP physicians in Nepal possess unique skills tailored to the country’s diverse and challenging health care landscape, making their scope of practice wider than family physicians in many countries; it includes primary care of acute and chronic illness for all ages of children and adults, preventive, emergency, mental health, and rehabilitative care, emergency obstetric and surgical procedures, triaging of patients (in emergency and outpatient settings), planning and policy formation, clinical research, and teaching. The contributions of family physicians demonstrate utilization of the skills learned in the Nepali family medicine residency and adaptation to the changing needs of their country. 12, 14, 15, 16, 17

As specialized medical institutions increase, but training positions in family medicine do not, Nepal’s population continues to face inequitable medical coverage, particularly in remote, rural areas. Recruitment and retention are not increasing, despite recent government support for MDGP residency programs such as Karnali Academy of Health Sciences in rural, high-altitude areas with poor health care indices, and even with increased advocacy by family/MDGP physicians themselves to increase their numbers to reduce health disparities. Challenges in recruiting medical students include lack of exposure during the undergraduate curriculum and perceived lack of opportunity for future advancement, pay, and quality of life.30, 31 A 2008 survey of MDGP residents found that the most critical factors in promoting retention in rural areas were career development, recognition, financial incentives, working conditions, and education for children.32 A successful 3-year incentive program offered such a package of human resources (central personnel management, performance-based incentives, comfortable accommodation, and a service scholarship) as support to family doctors who could perform advanced obstetric, surgical, and orthopedic care. The results were a 100% retention of the family physicians in seven rural hospitals.14 Unfortunately, these practices have not been adopted nationally.33 Challenges with a preponderance of patients presenting late for care or refusing treatment due to lack of resources or lack of understanding are also deterrents for retention in some areas.34 A 2023 survey of family/MDGP physicians cited major challenges to recruitment and retention because of poor health policy and lack of governmental recognition of their specialty as first contact physicians for primary care. They requested more seats for family medicine training, improved working environment, improved salary, improved opportunities for continuing medical education and fellowships, and a robust primary care system led by MDGPs. 33

In 2024 a group of family/MDGP physicians proposed strategies and solutions to advance family medicine: the General Practice Reformation Agenda. The recommendations were developed after focused group discussions, interviews, polls, debates, and panel discussions on key issues and their potential solutions, with many practicing family physicians. They group noted a pressing need for a centralized outpatient department system led by family/MDGP physicians, recognition of their specialty and acknowledgment for their expertise and contributions, equal status to other specialties, increased integration into medical education, education of the public on their skills, monetary and status incentives to practice in underserved areas, and faculty development. 33

Nepalese educators and health leaders deserve commendation for their success in developing unique, local family medicine/MDGP residency programs, which have produced Nepali physicians with skills in primary and emergency care. Overcoming many obstacles over the past 25 years, they have decreased health disparities and improved the health of their nation. Their continued success, however, will depend on the support of their peers, the Ministry of Health, and the international medical education community. 33

*A graduate of a family medicine residency program, MDGP, previously referred to as a “Medical Doctor in General Practice," is now called a “Medical Doctor in General Practice and Emergency Medicine" in most institutions, reflecting increased focus on emergency medicine.

References

-

World Factbook. Nepal. Central Intelligence Agency. Accessed October 20, 2024. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/nepal

-

Ackerman L, Karki P. Family practice training in Nepal. Fam Med. 2000;32(2):126-128. https://www.stfm.org/familymedicine/vol32issue2/Ackerman126

-

United Nations Development Programme. Nepal: sustainable and economic transformation. Accessed October 19, 2024. https://www.undp.org/nepal/inclusive-economic-growth

-

Adhikari B, Mishra SR, Schwarz R. Transforming Nepal’s primary health care delivery system in global health era: addressing historical and current implementation challenges. Global Health. 2022;18(1):8. doi:10.1186/s12992-022-00798-5

-

Marasini B. Health system development in Nepal. J Nepal Med Assoc. 2020;58(221):65-68. doi:10.31729/jnma.4839

-

Ghimire PR, Agho KE, Ezeh OK, Renzaho AMN, Dibley M, Raynes-Greenow C. Under-five mortality and associated factors: evidence from the Nepal demographic and health survey (2001-2016). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(7):1,241. doi:10.3390/ijerph16071241

-

Ministry of Health and Population. A Report on Maternal Mortality. National Statistics Office; 2023. Accessed October 15, 2024. mohp.gov.np

-

Department of Health Services, Nepal. The Nepal Health Facts Sheet 2023. Accessed October 15, 2024. https://dohs.gov.np/national-health-facts-sheet-2023

-

Department of Health Services, Nepal. Annual Health Report 2079/80 (2023-4). Accessed October 12, 2024. https://dohs.gov.np/category/annual-report

-

Karki BK, Kittel G. Neonatal mortality and child health in a remote rural area in Nepal: a mixed methods study. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2019;3(1):e000519. doi:10.1136/bmjpo-2019-000519

-

Nepal Medical Council. Universities and colleges. Accessed October 15, 2024. https://nmc.org.np

-

Gauchan B, Mehanni S, Agrawal P, Pathak M, Dhungana S. Role of the general practitioner in improving rural healthcare access: a case from Nepal. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1):23. doi:10.1186/s12960-018-0287-7

-

Gupta A, Prasad R, Abraham S, et al. Pioneering family physicians and the mechanisms for strengthening primary health care in India: a qualitative descriptive study. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023;3(6):e0001972. doi:10.1371/journal.pgph.0001972

-

Zimmerman M, Shah S, Shakya R, et al. A staff support programme for rural hospitals in Nepal. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(1):65-70. doi:10.2471/BLT.15.153619

-

Dangal B, Kwan Ng JY, Gauchan B, Khadka MB, Pathak M. Role of general practitioners in transforming surgical care in rural Nepal: a descriptive study from eastern Nepal. J Gen Pract Emerg Med Nepal. 2021;8(11):5-9. doi:10.59284/jgpeman70

-

Maru S, Bangura AH, Mehta P, et al. Impact of the roll out of comprehensive emergency obstetric care on institutional birth rate in rural Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):77. doi:10.1186/s12884-017-1267-y

-

Agrawal P, Giri B, Gupta P, Nepali A, Parajuli S. Utilization of diagnostic services at a municipal hospital in rural Nepal: perspective from a general practitioner-led primary care delivery. J Gen Pract Emerg Med Nepal. 11(17), 62–66.

-

Karnali Academy of Health Sciences. Website. Accessed October 20, 2024. https://kahs.edu.np

-

Krishna Gupta T, Bhattarai K, Pal A, Kasaudhan SM, Manandhar N. Outcome of Covid 19 patients admitted in emergency department of Karnali Academy of Health Sciences, teaching hospital. Journal of College of Medical Sciences Nepal. 2023;19(1):82-88. doi:10.3126/jcmsn.v19i1.53330

-

Acharya B, Tenpa J, Basnet M, et al. Developing a scalable training model in global mental health: pilot study of a video-assisted training program for generalist clinicians in rural Nepal. Glob Ment Health (Camb). 2017;4:e8. doi:10.1017/gmh.2017.4

-

Pal A, Kumar Yadav M, Krisha Gupta T. Assessing severity of chronic obstructive lung diseases (COPD) using CAT score among high altitude residents of Nepal. Nepal Med J. 2022;5(1):39-44. doi:10.37080/nmj.135

-

Dangal B, Kharal PM. General practitioners tackling burden of non-communicable diseases in primary care setting of Nepal: way forward: GP managing non-communicable diseases. J Gen Pract Emerg Med Nepal. 2023;10(15):60-62. doi:10.59284/jgpeman221

-

Gyawali B, Thapa N, Savage C, et al. Training general practitioners in oncology: a needs assessment survey from Nepal. JCO Glob Oncol. 2022;8(8):e2200113. doi:10.1200/GO.22.00113

-

Kharal PM. Triaging of patients by general practitioners (GPs) in primary health care settings: a neglected aspect in the health policy & practice in Nepal: triaging of patients by GP in primary health care. J Gen Pract Emerg Med Nepal. 2023;10(15):40-44. doi:10.59284/jgpeman210

-

Gupta TK, Kasaudhan SM, Paudyal V, et al. Pattern and clinical outcome of poisoning cases admitted in emergency department of a tertiary care center at high altitude Nepal. SCIREA J Clin Med. 2023;8(2):130-140. doi:10.54647/cm321050

-

Gupta TK, Kasaudhan SM, Paudyal V, et al. Patterns of ENT problems under general practice in rural hospital of high altitude. Journal of Chitwan Medical College. 2023;13(1):43. doi:10.54530/jcmc.1266

-

Bhandari SS, Adhikari S. Emergency medicine in Nepal: are we going the right way and fast enough? Int J Emerg Med. 2023;16(1):79. doi:10.1186/s12245-023-00553-6

-

Lewis M, Smith S, Paudel R, Bhattarai M. General practice (family medicine): meeting the health care needs of Nepal and enriching the medical education of undergraduates. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2005;3(2):194-198.

-

Shrestha S, Shrestha A, Shah JN, Gongal RN. Competency based post graduate residency program at Patan Academy of Health Sciences, Nepal. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2021;19(1):189-195. doi:10.33314/jnhrc.v19i1.3263

-

Kushwaha A, Kadel AR. Attitude of interns towards family medicine as a career in a tertiary care hospital. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2019;57(219):361-363. doi:10.31729/jnma.4634

-

Hayes BW, Shakya R. Career choices and what influences Nepali medical students and young doctors: a cross-sectional study. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11(1):5. doi:10.1186/1478-4491-11-5

-

Butterworth K, Hayes B, Neupane B. Retention of general practitioners in rural Nepal: a qualitative study. Aust J. Rural Health. 2008;16(4):201-206. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1584.2008.00976.x

-

Shrestha A, Ghimire R, Bajracharya S, et al. General practice reformative agenda, 2024. J Gen Pract Emerg Med Nepal. 2024;11(17):106-123. doi:10.59284/jgpeman279

-

Hansen KL, Bratholm Å, Pradhan M, Mikkelsen S, Milling L. Physicians’ experiences and perceived challenges working in an emergency setting in Bharatpur, Nepal: a qualitative study. Int J Emerg Med. 2022;15(1):61. doi:10.1186/s12245-022-00466-w

Lead Author

Tula Krishna Gupta, MD

Affiliations: Department of General Practice and Emergency Medicine, Karnali Academy of Health Sciences, Jumla, Nepal

Co-Authors

Lani Kay Ackerman, MD - Department of Clinical Sciences, Tilman J. Fertitta Family College of Medicine, University of Houston, Houston, TX, USA

Corresponding Author

Lani Kay Ackerman, MD

Correspondence: Department of Clinical Sciences, Tilman J. Fertitta Family College of Medicine, University of Houston, Houston, TX, USA

Email: lkackerm@central.uh.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.