Qualitative study designs provide critical insights into pressing health care problems by answering why, how, and what questions: Why do patients not adhere to medications? How do providers use guidelines? What clinic features contribute to quality of care? Qualitative methods often consist of interviews or focus groups but also can include observations or archival data. These methods elucidate patient and provider experiences, behaviors, or beliefs; describe phenomena; and provide rich insights into local contexts. While family medicine has long acknowledged the value of qualitative research, clinicians and medical educators may have limited exposure. Our objectives are to (a) orient clinicians to qualitative research, and (b) guide them through the stages of qualitative study design, from planning, to data collection, to analyses, on through dissemination of a final product. We describe the tenets of qualitative inquiry: an insider perspective, holism, attention to power dynamics, reflexivity, and flexibility. We explain how to choose among qualitative data collection methods, such as interviews, focus groups, observation, and archival data review. Lastly, we provide key considerations for analyzing qualitative data, disseminating final product(s), and maximizing methodological quality. This practical guide for clinicians gives a grand tour of the overall purpose of and approaches to qualitative study designs and offers considerations when using qualitative methods in research and quality improvement studies.

AN INTRODUCTION TO QUALITATIVE METHODS AND WHY TO USE THEM

Why do patients not take their medications? How do family physicians juggle guidelines in the context of competing demands? What types of contextual factors contribute to a clinic’s quality of care? These questions are ripe for qualitative inquiry because they are socially complex, contextual, and benefit from people’s perspectives and experiences. Qualitative research can provide patient perspectives on adherence,1,2,3 explore providers’ experiences providing guideline concordant care,4,5,6,7 or describe clinic contexts.8,9,10

Family medicine has long valued qualitative research because it provides a deep, holistic understanding of health care problems.11,12,13 Qualitative methods can yield information unobtainable through quantitative research, such as the tension family doctors experience when caring for patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain14 or why some physicians continue to order lumbar spine MRIs for uncomplicated low back pain despite limited evidence supporting improved outcomes.15 Qualitative inquiry facilitates understanding of behaviors, beliefs, and experiences, and can provide insightful explanations informed by local contexts.16,17,18 Moreover, qualitative data illuminates the meaning people ascribe to behaviors and practices, such as the role of the physical exam in family medicine.19

CONCEPTUALIZING QUALITATIVE STUDIES

Qualitative studies are foundationally and epistemologically distinct from quantitative studies, meaning that the principles underlying the approaches are different.13,20 In qualitative research, the goal is often describing, exploring, or explaining a phenomena of interest. Quantitative and qualitative methods have different disciplinary traditions, approaches to data collection and analysis, and methods for assessing rigor.18,20 For example, we (the authors of this manuscript) are medical anthropologists; we draw from the tenets of our training to inform qualitative study designs (Table 1) that (a) provide an emic, insider perspective, (b) are holistic, (c) attend to power dynamics, (d) are reflexive, and (e) are used flexibly.13

Qualitative study design term |

Key features |

Audit trail |

Qualitative researchers document data collection procedures to ensure rigor.

Documents the researcher’s logic Records research steps and decisions from early in the research process Might include information such as inclusion/exclusion criteria, frequency of contact, number of responses, and/or participants lost to follow-up and why Can be used as a reference during the writing process |

Emic perspective |

Qualitative researchers emphasize the importance of understanding the emic perspective.

Emic perspective: the insider’s or participant’s perspective (eg, patient or health care staff who are interviewed) Etic perspective: the outsider’s or nonparticipant’s perspective (eg, researcher or health care staff who conduct the interview) |

Flexibility |

Qualitative researchers employ flexible methods.

-

Sampling that may be iterative -

Data collection that is often semi-structured -

Data collection and analysis that are often iterative over time

|

Holistic approach |

Qualitative researchers employ a comprehensive, big picture view of research (e.g., people living with HIV: illness/lived experiences, disease impacts, environmental factors, health care access, local contexts, how cultural beliefs and values impact lived experiences).

Includes perspectives of diverse people on team Considers research problem from diverse perspectives (eg, a multifaceted understanding) Incorporates diverse types of data (eg, interviews, medical record) Includes diverse types of participants Includes the participant’s lived experiences |

Power dynamics |

Qualitative researchers recognize the importance of how power dynamics impact the research or quality improvement process in various ways.

Data collection: who conducts the interview or leads data collection in relation to the participant and why a provider interviewing patients may be problematic (eg, focus group composition may be hindered if power dynamics are not considered) Analysis: how the researcher’s role and background can impact analysis and presentation of results |

Purposive sampling |

Qualitative researchers typically employ purposeful sampling to obtain rich information about people, contexts, or settings. This approach differs from probability sampling or sampling to make generalizations about a population. Following are various ways purposeful sampling is performed:

Criterion sampling (for specific characteristics) Homogeneous sampling (for similar characteristics) Snowball sampling (through word of mouth) Maximum variation (to enhance diversity) |

Transferability |

Qualitative researchers do not aim to achieve generalizability. Instead, qualitative research uses transferability, which is based on the reader’s determination whether study results apply to different contexts, settings, or populations. Transferability is enhanced in various ways:

Rich description of the results and population of interest Use of theories, models, or frameworks to help translate results in a relatable way or make comparisons across different contexts Clear presentation of results so that readers understand the findings |

Tenets of Qualitative Research

An insider perspective, gained through asking study participants open-ended questions, is among the hallmarks of qualitative research.13 The perspective of doctors, patients, or community members can illuminate why they think or act the way they do. Gaining an insider perspective might include interviewing patients on the barriers they experience taking medication as prescribed or conducting observations of clinic routines to explain practice variation.10,21,22,23

Holism means understanding issues comprehensively. Researchers can apply a holistic perspective to a problem by incorporating multiple methods (eg, interviews and observation), eliciting diverse perspectives (eg, patient and clinician), or combining data (eg, qualitative and quantitative). For example, understanding medication adherence is multifaceted and complex, and thus benefits from combining methods and perspectives. One approach might entail pairing medical record data documenting prescriptions, patient demographics, health conditions, and provider notes with patient interviews.24 A holistic approach can help describe features of the organizational context where an evidence-based practice (eg, mental health in primary care) is being implemented.25

Attention to power means considering the study population, how people relate to others, and the broader systems in which they live and work.13,26,27 Medicine is inherently hierarchical, with roles having varying levels of power.26 These power dynamics have implications for the study design, such as the composition of a focus group. A heterogenous mixture of doctors and nurses might limit the scope of topics raised and stifle open discussion, while a homogenous group of patients with the same disease or condition promotes nuanced discussion about life experiences. Similarly, power differentials can constrain conversations between the interviewer and participant (eg, a doctor and patient). Unique risks exist when a doctor interviews patients for a research study. Steps can be taken such as not interviewing patients in your own clinic or avoiding formal titles. These approaches do not entirely remove power differentials because hierarchical differences remain between patients and doctors. Power and hierarchy are linked to social attributes (eg, race, gender, age, disability, religion, economic status, education). These factors influence how people interrelate and how they interact with researchers.

Reflexivity, which is related to power, means considering team members’ roles and experiences—their unique backgrounds, histories, and training (ie, their positionality), and how these affect data collection or analysis. For example, a social scientist and clinician would draw upon different training and experiences while conducting an interview about a disease and would understand data differently during analysis. These distinct perspectives can be desirable and can impact how data are understood. A study about routine clinic practices might be informed by a clinician’s work experiences, while a social scientist might ask insightful, open-ended questions because they are unfamiliar with clinic operations or disease treatment. A best-case scenario can occur when social scientists and clinicians work together, each bringing their distinct lens to research questions and data. One author (L.K.) includes family physicians in her qualitative research projects, melding clinical and anthropological experiences and insights.28 The reflexive process can be facilitated by having team members write (using analytic memos)29 or talk about how their training and experiences inform their understanding of the research problem.

Qualitative study designs can be used flexibly.30 Flexibility may include how an interview guide is used or who is interviewed. Qualitative interview guides should guide conversations. The interviewer may change the order of questions or omit and add questions depending on what the participant is sharing. Interviewers might probe to delve deeper into why a participant made a particular statement. Flexibility also may occur when novel or unexpected information is gathered during interviews, necessitating alterations in the study design. For example, if patient interviews emphasize family members’ roles in medication adherence, future interviews could expand to family members either in interview guide questions or as additional participants.

We have found that early practitioners, who might be more familiar with structured survey questions, find the concept of flexibility useful when embarking on qualitative studies. When submitting protocols to an institutional review board (IRB), we explain that the qualitative interview is a guided conversation rather than a fixed questionnaire. However, significant alteration of the interview protocol, such as an entirely new line of inquiry, may require submitting an IRB amendment.

DESIGNING QUALITATIVE STUDIES

A qualitative study design is comprised of specific methods, such as interviews, focus groups, observation, and/or archival (existing) data (Table 2). The design is the broader framework, of which the methods are just one part.

Method |

Best use |

Considerations |

Examples |

Interviews |

|

Good for personal experiences, including taboo topics Different from clinical interviews or getting a medical history31 Be mindful of power dynamics13 Need~10 participants per group of interest as a general starting point3 |

Common population include:

Patients Providers Hospital staff Hospital leadership Community members Family members Caregivers |

Focus groups |

|

Limited number of questions Challenging to recruit people for the same time Power dynamics matter (homogenous) People with something in common (eg, same disease or training or work setting) The N is the number of focus groups, not participants17 Typically need at least 2–4 focus groups to compare and analyze33 |

|

Observation |

|

Not good for taboo or infrequent behaviors34,40 Need permission to access space Specify what is/is not being observed13 |

|

Archival data |

|

Not good for exploratory work Static information Limited to what was already reported Often used to complement primary data collection rather than replace it |

Meeting notes Medical records Social media posts |

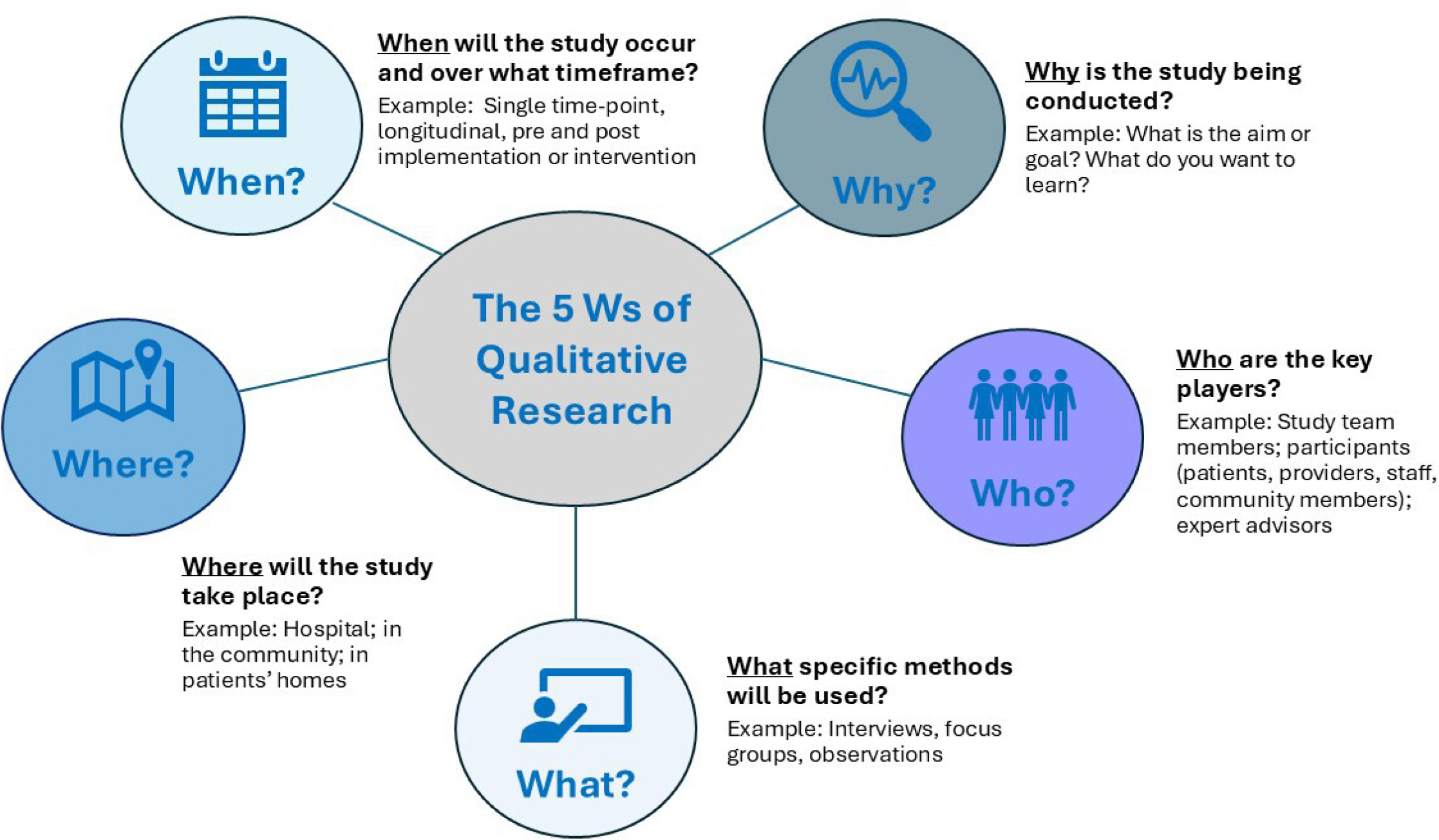

The Five W’s of Qualitative Research: Why, Who, What, Where, When

When designing a qualitative study, consider the five W’s of qualitative research (Figure 1).

Why is the study being conducted? Is the study exploratory (unknown topic); explanatory (expand on quantitative results); or descriptive (describe human experience or problem)?35 The research question (what you want to learn) should guide the methods and approach.

Who are the key players? Who specifically should be included/excluded as a participant? Who will be on the study team?

Where will the study take place? At the hospital, in the community, in patients’ homes?

What data collection methods will be used (eg, interviews, focus groups, observation)?

When will the study occur and over what time frame?

THE STAGES OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

In keeping with the practical nature of this article, here we provide an overview of the four stages of conducting qualitative research. Stage 1, planning, includes thinking about goals, approach, team members, and time frame. Stage 2, data collection, guides what methods will be used and how participants will be identified and recruited. Stage 3, analysis, informs what will be done with the data once collected. Stage 4, dissemination, focuses on the product or end goal, typically a manuscript. Thinking of these as stages helps make connections across the research process. Although we present these stages linearly, they often are iterative.

Stage 1. Planning

Thoughtful planning (Table 3) is critical to rigorous work.13 Planning includes thinking through key components: objective, methods, team members, analysis, timeline, approvals, budget (including participant compensation and transcription), and end product(s). A primary focus should be on the research question; this focus guides all the work. What is the study goal, and which strategies (methods) align with the goal(s)?

Component |

Considerations |

Objective |

What is the specific goal of the work?

What do you want to accomplish?

Are qualitative methods (eg, exploratory, descriptive, explanatory) appropriate? |

Method(s) |

Which methods (eg, interview, focus groups, observation, archival data) can help answer the question(s)?

Are quantitative methods (eg, survey, medical record) also needed? |

Team |

What work needs to be done?

Who has the skills or training to complete the project? |

Analysis |

What data will you have and what do you want to learn from it?

What analytic approach will you use?

Who is on the analytic team?

How will you disseminate (eg, conference, manuscript, report) the findings? |

Timeline |

What is the time frame?

How long will it take to accomplish all the steps (eg, funding, training team members, institutional review, data collection, data analysis, dissemination)? |

Approval |

What official approvals are needed?

What informal permission (eg, head nurse) is needed? |

Dissemination |

What are the end products (eg, executive summary, manuscript)? |

Qualitative methods can stand alone or be paired with quantitative data (mixed methods). In mixed-method study designs, how the methods relate to each other, the order they are conducted, and how data are integrated should be specified.35

Typically, qualitative researchers are engaged in primary data collection and involved in recruitment, scheduling, and then conducting interviews, focus groups, or observations. These activities can be labor-intensive and benefit from a team approach. Thus, qualitative research is often conducted by a multidisciplinary team, with members assuming distinct roles. The study lead is responsible for conceptualizing the research and securing the funding as well as ensuring methodological quality. Additionally, team members might include a project manager overseeing study logistics, a research assistant helping with daily tasks, and a methodologist/analyst helping collect and analyze data. Trainees, such as medical students, residents, or fellows, can learn and contribute. Studies also may include other investigators who provide content or methods expertise. Frequently, as team members, family medicine clinicians are introduced to qualitative methods, working alongside a mentor or research associate. Experienced qualitative team members support the entire process, from conceptualization through the final product. They help ensure rigor and enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of the data and findings.36

Stage 2. Data Collection

Selection of data collection methods depends on the research question(s) and population(s) of interest (eg, who the study participants are). Interviews entail a one-on-one conversation, which is good for in-depth understanding of a single person’s experiences. An interview may sound like a conversation, but it is a highly orchestrated discussion facilitated by the interviewer.37 Interviews can be repeated with the same person over time. Interview data are then compiled across participants to give a rich view of the phenomena of interest.

Focus groups comprise a group conversation where people share and compare ideas in relation to a topic.38,39 These are effective for generating ideas around a subject of interest and offer breadth of a topic over depth. The interview or focus group guides are informed by the study goals and the best ways to ask participants questions. Interviews and focus groups are common data collection types in health services research and quality improvement, but observation and archival data offer additional ways to gain qualitative insights.

Observations provide understanding of conversations, processes, interactions, and behaviors that are difficult for people to remember or explain, and are useful for documenting implicit actions often done without thinking.40 Observations illuminate behaviors in context. While concern might exist, observing participants is unlikely to change their behavior.35

Archival data consists of existing data, such as meeting minutes, clinical guidelines, and information from the electronic health record, websites, educational materials, or historical records.13 These can be analyzed for historical trends, provide objective documentation or inform primary data collection.

Key to qualitative data collection is data organization.13 Project and data management in qualitative research are sometimes overlooked. We recommend that the team develop data management plans early in the study. This includes the participant identification system, file organization and naming, where data will be stored, how data will be organized for analysis and shared with analysts, and the like. Keeping track of recruitment and participation data through spreadsheets can later help characterize the population for reporting. This organization is particularly important when the study has different types of data, different participant types, or different phases of qualitative research.

Additional factors to consider are timelines, approvals, and final products. Funding or educational goals often inform study timelines. Studies typically are reviewed by an independent party, such as an IRB, to determine whether the activity is research or quality improvement, each with specific guidelines. A GANTT chart (a timeline with activities mapped to study month) helps researchers consider each step and how long it takes from approvals through the end product.

Researchers should clearly specify selection and inclusion criteria for participants. Who are you trying to reach? What are the eligibility criteria? How will you reach potential participants? How many people do you need to speak with? Sampling in qualitative studies is not about having enough people for a representative sample of the population. Instead, the goal is to speak with the right mixture of people to feel confident about answering the research question. Determining sample size is highly dependent on the goals of the work and disciplinary tradition, although some rough principles are outlined.41,42,43,44 Purposive sampling is a focused strategy to obtain rich information from cases aligned with the research question.44,45

Recruitment is labor intensive. Reaching potential participants can take multiple tries. IRBs may have rules about contacting potential participants to minimize coercion, while participants may be more responsive to certain forms of outreach. Mailed letters, emails, phone calls, text messages, and even instant messaging can be viable recruitment strategies. Busy clinicians may be overloaded with emails, but receptive to instant messages.46 To facilitate recruitment, team members or an advisory group can help identify strategies, such as asking collaborators to connect you to potential participants. We have found recruiting clinicians in person, during routine staff meetings or didactic sessions, fruitful. Social media can help reach potential participants, but may tempt people who are not the population of interest but are instead interested in compensation.47 Recruitment outside a clinical setting, in a community, can take additional work. Succinctly providing the purpose of the study and what is being asked of participants can increase participation.

Compensating participants with cash payments or gift cards is a gesture of respect for their time and expertise. Others in your institution or related fields should be consulted to identify a going rate. Institutions vary regarding who can be paid. Employee payments typically depend on employer rules (eg, some institutions do not allow staff compensation).

Stage 3. Analysis

The analysis phase can be challenging, especially for those new to qualitative research. Qualitative analysis is iterative and focuses on making meaning of the data. It often involves identifying concepts or themes across interviews, focus groups, observations, or archival data. Qualitative analysis has a different rhythm from quantitative analysis, and researchers can benefit from working with experienced team members. Planning for analysis should come early in the process. Avoid collecting volumes of qualitative data, only to be stuck trying to figure out what to do next.

A range of qualitative methodological approaches and analysis techniques are available. The approach should match the study objectives, data collected, and ultimate goal. For example, if the goal is to be more descriptive and less interpretive, you would conduct interviews that encourage participants to describe their experiences. You could then use thematic analysis to understand the various aspects of participants’ experiences.

Common approaches used in health research include content analysis,48 which focuses on categories in the data; thematic analysis,49 which identifies patterns of meaning; and rapid analysis,50 which is a streamlined approach for rapid turnaround projects; as well as many other useful approaches. This introductory article provides only a brief synopsis. For more information on qualitative analysis, see Saldaña for an overview of coding qualitative data51 or Starks and Brown Trinidad52 for a comparison of methods such as phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Further readings are provided in Table 4 for specific approaches.

Approach |

Description |

Further reading |

Case study |

Focused on the individual cases or settings (eg, people who adhere to medications; clinics that prescribe more vs less appropriately; departments that adopt a new initiative or program) |

Baškarada S. Qualitative case study guidelines. The Qual Rep. 2014;19(40):1–25.

Stake, RE. Qualitative case studies. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry. 3rd ed. Sage; 2008:119–149. |

Content analysis |

Focused on language and categories in the data. More useful when categories are specified a priori or using a framework |

Hsieh, H-F, Shannon, SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1,277–1,288. |

Discourse analysis |

Examination of narrative or conversations between people. Useful for patient-provider communication and health care staff interactions |

Eggly, S. Physician-patient co-construction of illness narratives in the medical interview. Health Commun. 2002;14(3):339–360.

Koenig, CJ. Discourse/conversation analysis. In: Ho EY, Bylund CL, Van Weert JCM, et al, eds. The International Encyclopedia of Health Communication. Wiley; 2023.

Rejnö, A, Berg L, Danielson E. The narrative structure as a way to gain insight into peoples’ experiences: one methodological approach. Scand J Caring Sci. 2014;28(3):618–626. |

Phenomenology |

Focuses on understanding and describing the lived experience of a specific phenomenon |

Starks H, Brown Trinidad S. Choose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(10):1,372–1,380. |

Pragmatic ethnography |

A holistic, multimethod approach focused on understanding the insider, emic perspective |

Hamilton AB, Fix GM, Finley EP. Pragmatic Healthcare Ethnography: Methods to Study and Improve Healthcare. 2024; Routledge. |

Rapid analysis |

Streamlined yet systematic approach for more rapid turnaround projects |

Kowalski CP, Nevedal AL, Finley EP, et al. Planning for and assessing rigor in rapid qualitative analysis (PARRQA): a consensus-based framework for designing, conducting, and reporting. Implement Sci. 2024;19:71.

Nevedal AL, Reardon CM, Opra Widerquist MA, et al. Rapid versus traditional qualitative analysis using the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR). Implement Sci. 2021;16(1):67. |

Thematic analysis |

Identifies patterns of meaning |

Clarke V, Braun V. Thematic analysis. J Posit Psychol. 2017;12(3):297–298. |

Stage 4. Dissemination

Researchers should consider potential dissemination products early in the planning process. What are you hoping to deliver at the end of the project? Consider what kind of product you are expecting: report, presentation, manuscript, and so forth. Focusing on the final product can provide purpose, a timeline, and closure. Qualitative products typically support findings with quotations, which are the data derived from the interviews or focus groups. Archival data or field notes from observations are less common, but appropriate.40,53 Qualitative quotes can provide a rich narrative exploring the study question. Quotes can and should be integrated into the products. Visual displays and matrices also can be a useful way to communicate findings.54

Other considerations for dissemination are who is leading the effort, required approvals for sharing results, and, if publishing a manuscript, which journal might be a good fit. We have found targeting journals that publish qualitative papers to be helpful.13 Some journals may require a methods checklist, while others prefer the inclusion of the interview or focus group guide; however, these are not necessary to demonstrate rigor.55

The features of a qualitative study design necessitate different strategies to assess rigor compared to quantitative studies.17,18,36,56,57,58,59,60,61 Using quantitative standards to design and assess rigor in qualitative methods, such as generalizability, a preference for large sample sizes, and representativeness are inappropriate for qualitative studies.55 Instead, transferability is the extent to which the reader determines whether study results are applicable to other settings or contexts. Transferability is enhanced with rich descriptions, clear presentation of study results, and/or the use of theories, models, or frameworks.55 Transparency is a closely related process where the researcher is clear (and transparent) about what steps they took. Audit trails are a strategy to document data collection procedures.62 Capturing details throughout the data collection process allows for thick, rich description of the study procedures, which is a marker of quality. Overall, the fit between the study goals and the data collection procedures are good metrics of qualitative rigor.50,56,57

Available resources such as the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research59 or Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research60 provide basic guidance for rigor. These criteria can be used as a guide to identify steps to include in the study design and writing. Following the principle of flexibility, qualitative studies may not adhere to every aspect of the checklist. Thus, caution should be taken because checklists may miss valuable aspects of the study, such as originality or the substance of the findings.61

This practical guide for clinicians gives a grand tour of the overall purpose of and approaches to qualitative study designs and offers key considerations when using qualitative methods. By providing this guidance, we aim to help clinicians understand how qualitative methods are rigorous and can answer diverse health care delivery questions.

This material is based upon work supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research, and Quality Enhancement Research Initiative. Dr. Fix is supported by IIR 21-215; Drs. Fix and Nevedal are supported by PEC17-002. Dr. Nevedal is supported by the Rapid Qualitative Methods for Implementation Practice Hub (QIS 22-234) and QUE 20-012.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

G.F. developed the initial draft. All authors (G.F., A.N., L.K.) then contributed to and revised all sections of the manuscript. All authors were involved in the revisions and then read and approved the final manuscript.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

References

-

Nicosia FM, Spar MJ, Stebbins M, et al. What is a medication-related problem? A qualitative study of older adults and primary care clinicians.

J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(3):724–731. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05463-z

-

Herrera PA, Moncada L, Defey D. Understanding non-adherence from the inside: hypertensive patients’ motivations for adhering and not adhering.

Qual Health Res. 2017;27(7):1023–1034. doi:10.1177/1049732316652529

-

van der Straten A, Stadler J, Montgomery E, et al. Women’s experiences with oral and vaginal pre-exposure prophylaxis: The VOICE-C qualitative study in Johannesburg, South Africa.

PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e89118. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089118

-

Solomon JL, Gifford AL, Asch SM, et al. How do providers prioritize prevention? A qualitative study. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(10):e342–7.

-

Gani I, Litchfield I, Shukla D, Delanerolle G, Cockburn N, Pathmanathan A. Understanding “Alert Fatigue” in primary care: qualitative systematic review of general practitioners attitudes and experiences of clinical alerts, prompts, and reminders.

J Med Internet Res. 2025;27. doi:10.2196/62763

-

Tuepker A, Zickmund SL, Nicolajski CE, et al. Providers’ note-writing practices for post-traumatic stress disorder at five United States veterans affairs facilities.

J Behav Health Serv Res. 2016;43(3):428–442. doi:10.1007/s11414-015-9472-9

-

Vest BM, York TRM, Sand J, Fox CH, Kahn LS. Chronic kidney disease guideline implementation in primary care: a qualitative report from the TRANSLATE CKD study.

J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(5):624–631. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2015.05.150070

-

Crable EL, Biancarelli DL, Aurora M, Drainoni M-L, Walkey AJ. Interventions to increase appointment attendance in safety net health centers: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

J Eval Clin Pract. 2021;27(4):965–975. doi:10.1111/jep.13496

-

Lacy NL, Paulman A, Reuter MD, Lovejoy B. Why we don’t come: patient perceptions on no-shows.

Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(6):541–545. doi:10.1370/afm.123

-

Bokhour BG, Bolton RE, Asch SM, et al. how should we organize care for patients with human immunodeficiency virus and comorbidities? A multisite qualitative study of human immunodeficiency virus care in the United States department of veterans affairs.

Med Care. 2021;59(8):727–735. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001563

-

Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Sage; 1999.

-

Webster F, Rice K. Corrigendum: Conducting ethnography in primary care.

Fam Pract. 2019;36(6). doi:10.1093/fampra/cmz061

-

Hamilton AB, Fix GM, Finley EP. Pragmatic Healthcare Ethnography: Methods to Study and Improve Healthcare. Routledge; 2024.

10.4324/9781003390657

-

Desveaux L, Saragosa M, Kithulegoda N, Ivers NM. Family physician perceptions of their role in managing the opioid crisis.

Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(4):345–351. doi:10.1370/afm.2413

-

Nevedal AL, Lewis ET, Wu J, et al. Factors influencing primary care providers’ unneeded lumbar spine mri orders for acute, uncomplicated low-back pain: a qualitative study.

J GEN INTERN MED. 2020;35(4):1044–1051. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05410-y

-

Guest G, Namey EE, Mitchell ML. Collecting Qualitative Data: A Field Manual for Applied Research. Sage; 2013.

10.4135/9781506374680

-

Hamilton AB, Finley EP. Qualitative methods in implementation research: an introduction.

Psychiatry Res. 2019;280:112516. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112516

-

Sofaer S. Qualitative methods: what are they and why use them? Health Serv Res. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1101–1118.

-

Kelly MA, Freeman LK, Dornan T. Family physicians’ experiences of physical examination.

Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(4):304–310. doi:10.1370/afm.2420

-

Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. Choosing Among Five Traditions. Sage; 1998.

-

Gillespie C, Rose AJ, Petrakis BA, Jones EA, Park A, McCullough MB. Qualitative study of patient experiences of responsibility in warfarin therapy.

Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(22):1798–1804. doi:10.2146/ajhp170736

-

Hahlweg P, Härter M, Nestoriuc Y, Scholl I. How are decisions made in cancer care? A qualitative study using participant observation of current practice.

BMJ Open. 2017;7(9). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016360

-

Bolton RE, Bokhour BG, Hogan TP, Luger TM, Ruben M, Fix GM. Integrating personalized care planning into primary care: a multiple-case study of early adopting patient-centered medical homes.

J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(2):428–436. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05418-4

-

Fix GM, Dryden EM, Boudreau J, Kressin NR, Gifford AL, Bokhour BG. The temporal nature of social context: insights from the daily lives of patients with HIV.

PLoS One. 2021;16(2). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246534

-

Ritchie MJ, Parker LE, Kirchner JE. Facilitating implementation of primary care mental health over time and across organizational contexts: a qualitative study of role and process.

BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1). doi:10.1186/s12913-023-09598-y

-

Fix GM, Kaitz J, Herbst AN, et al. Practical strategies for co-design: the case of engaging patients in developing patient-facing shared-decision making materials for lung cancer screening.

J Patient Exp. 2024;11. doi:10.1177/23743735241252247

-

Rogers L, De Brún A, Birken SA, Davies C, McAuliffe E. The micropolitics of implementation; a qualitative study exploring the impact of power, authority, and influence when implementing change in healthcare teams.

BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1059. doi:10.1186/s12913-020-05905-z

-

Kahn LS. Community, clinics, and courts: an applied anthropology journey.

Pract Anthropol. 2020;42(1):17–20. doi:10.17730/0888-4552.42.1.17

-

Rogers RH. Coding and writing analytic memos on qualitative data: a review of johnny saldaña’s the coding manual for qualitative researchers.

TQR. 2018;23(4):889–892. doi:10.46743/2160-3715/2018.3459

-

M. Frankel, Kelly J., Devers R. Study design in qualitative research-1: developing questions and assessing resource needs.

Education for Health: Change in Learning & Practice. 2000;13(2):251–261. doi:10.1080/13576280050074534

-

Hunt MR, Chan LS, Mehta A. Transitioning from clinical to qualitative research interviewing.

Int J Qual Methods. 2011;10(3):191–201. doi:10.1177/160940691101000301

-

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? an experiment with data saturation and variability.

Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. doi:10.1177/1525822X05279903

-

Guest G, Namey E, McKenna K. How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes.

Field Methods. 2017;29(1):3–22. doi:10.1177/1525822X16639015

-

Weston LE, Krein SL, Harrod M. Using observation to better understand the healthcare context.

Qual Res Med Healthc. 2021;5(3). doi:10.4081/qrmh.2021.9821

-

Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices.

Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6 Pt 2):2134–2156. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12117

-

Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1189–1208.

-

Patton M. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Sage; 2002.

-

-

-

Fix GM, Kim B, Ruben M, McCullough MB. Direct observation methods: a practical guide for health researchers.

PEC Innov. 2022;1. doi:10.1016/j.pecinn.2022.100036

-

Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales.

Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2021;13(2):201–216. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

-

Conlon C, Timonen V, Elliott-O’Dare C, O’Keeffe S, Foley G. Confused about theoretical sampling? Engaging theoretical sampling in diverse grounded theory studies.

Qual Health Res. 2020;30(6):947–959. doi:10.1177/1049732319899139

-

DiStefano AS, Yang JS. Sample size and saturation: A three-phase method for ethnographic research with multiple qualitative data sources.

Field Methods. 2024;36(2):145–159. doi:10.1177/1525822X231194515

-

Wutich A, Beresford M, Bernard HR. Sample sizes for 10 types of qualitative data analysis: an integrative review, empirical guidance, and next steps.

Int J Qual Methods. 2024;23. doi:10.1177/16094069241296206

-

Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research.

Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533–544. doi:10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

-

Wu J, Lewis ET, Barnett PG, Nevedal AL. Instant messaging: an innovative way to recruit primary care providers for qualitative research.

J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1612–1614. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05533-2

-

Medero K, Abdi H, Ford C, Gollust S. Detecting and preventing imposter participants: methods and recommendations for qualitative researchers.

Qual Health Res. 2025;0. doi:10.1177/10497323251333243

-

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis.

Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

-

-

Kowalski CP, Nevedal AL, Finley EP, et al. Planning for and assessing rigor in rapid qualitative analysis (PARRQA): a consensus-based framework for designing, conducting, and reporting.

Implement Sci. 2024;19(1). doi:10.1186/s13012-024-01397-1

-

Saldaña J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 4th ed. Sage; 2021.

-

Starks H, Trinidad SB. Choose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory.

Qual Health Res. 2007;17(10):1372–1380. doi:10.1177/1049732307307031

-

Fix GM, Hyde JK, Bolton RE, et al. The moral discourse of HIV providers within their organizational context: An ethnographic case study.

Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(12):2226–2232. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.018

-

Verdinelli S, Scagnoli NI. Data display in qualitative research.

Int J Qual Methods. 2013;12(1):359–381. doi:10.1177/160940691301200117

-

Nevedal AL, Kowalski CP, Finley EP, Fix GM, Hamilton AB, Koenig CJ. Optimizing qualitative methods in implementation research: a resource for editors, reviewers, authors, and researchers to dispel ten common misperceptions about qualitative research methods.

Implementation Sci. 2025. doi:10.1186/s13012-025-01474-z

-

Carminati L. Generalizability in Qualitative Research: A Tale of Two Traditions.

Qual Health Res. 2018;28(13):2094–2101. doi:10.1177/1049732318788379

-

LaDonna KA, Artino AR Jr, Balmer DF. Beyond the guise of saturation: rigor and qualitative interview data.

J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(5):607–611. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-21-00752.1

-

Tracy SJ, Hinrichs MM. Big tent criteria for qualitative quality.

: Matthes J, Davis CS, Potter RF, eds. The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods. Wiley; 2017.

10.1002/9781118901731.iecrm0016

-

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups.

Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

-

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations.

Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

-

Morse J. Why the

Qualitative Health Research (QHR) review process does not use checklists.

Qual Health Res. 2021;31(5):819–821. doi:10.1177/1049732321994114

-

Carcary M. Evaluating qualitative research—implementing the research audit trail. : Azzopardi J, ed. Proceedings of the 8th European Conference on Research Methods for Business and Management Studies. Valetta, Malta

There are no comments for this article.