Purpose: Rural family medicine residency programs (RFMRPs) encounter unique hardships that threaten their sustainability and efficacy despite their recent success at addressing the rural physician shortage. The aim of this study was to explore strategies employed by RFMRP program directors from across the United States to strengthen their programs in the context of evolving paradigms in graduate medical education (GME).

Methods: The authors conducted a qualitative semistructured telephone interview with 19 program directors of RFMRPs in June and July of 2020. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using thematic content analysis.

Findings: Two major themes emerged: (1) community enrichment and (2) the ability to evolve to meet demands. Community enrichment had five subthemes: evaluate local resources, prioritize community buy-in, design a robust continuity clinic, identify or cultivate a local physician champion, and support faculty and physician preceptors. Programs evolving to meet demands had four subthemes: frequently revisit program mission to align with scope of family medicine, redefine expectations in medical education, integrate longitudinal experiences, and implement innovation in curriculum design.

Conclusions: Community enrichment and programs’ ability to evolve to meet demands are important attributes of a successful RFMRP. Our findings highlight strategies utilized by RFMRPs to help meet the needs of the changing landscape of rural family medicine GME and help identify best practices for developing RFMRPs.

The shortage of rural physicians remains a public health issue despite the existence of targeted federal and state initiatives: 19% of the US population is rural, however only 11% of physicians practice in a rural area, indicating a severe shortage of rural physicians.1 Many reasons for this have been reported in the literature, along with recommendations and strategies for addressing the issue.1- 4 With the majority of rural general practitioners consisting of family physicians, rural communities may rely more heavily on family physicians to manage patients with complex diseases, compared to urban communities that have more access to specialists.1 A number of studies have demonstrated that rurally-trained residency graduates are more likely to work and stay in a rural area. 5- 9 One study showed that 60% of rural program graduates practiced in a rural area 4 years postgraduation.10 Thus, teaching institutions and medical organizations are exploring rural family medicine residency programs (RFMRPs) as a potential avenue to broaden graduate medical education (GME) opportunities and expand the rural physician workforce.11 The definition and different types of RFMRPs have been described in the literature,12- 14 and our data pool includes both rurally located and integrated rural training track programs.

As rural training programs have garnered more support,10, 11 roadmaps15, 16 have been put forth to help interested medical organizations and academic medical centers with RFMRP development, including a blueprint for assessing rural communities for potential development.17 In addition, goals and opportunities for RFMRP quality improvement have been described.18 One study used a qualitative approach to understand threats to family medicine rural training tracks’ sustainability and identify program resilience factors.19 Yet, there is a dearth of qualitative studies aimed at identifying strategies and best practices employed by program directors from RFMRPs.

This qualitative study explores common strategies and best practices employed by program directors from RFMRPs across the United States to strengthen their respective residency programs, including first-hand accounts of curricular adaptations and innovations used to overcome educational barriers. Understanding the perspectives of program directors is critical as they directly oversee the educational environment and make continuous improvements aligned with Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements.20 The findings from this study help characterize the essence of a successful RFMRP to help new and developing institutions create a more effective program and add qualitative insight to residency program development blueprints proposed in the literature.15, 17, 21- 24

We conducted a qualitative semistructed telephone interview using content analysis with a directed approach.

Sample and Setting

We emailed 99 US program directors listed on the publicly available Rural Training Track (RTT) Collaborative’s “Listing of Participating Programs” directory,25 inviting them to participate in a 30-minute telephone interview. We sent second email invitations to nonresponders after 1 month of initial email; 19 accepted the invitation in total.

Procedures

We developed a semistructured interview guide from methods of DiCicco-Bloom and Crabtree.26 The guide underwent internal testing27 with a medical education researcher with experience of qualitative methodologies (D.M.) and the corresponding author (T.M.), who has experience with developing a new RFMRP (Table 1).

|

• In what year did your program become accredited by ACGME and accept its first class?

• Can you tell me about your curriculum model?

a. What are the unique features of your program?

b. What factors did you have to consider when developing your curriculum?

c. What longitudinal experiences does your curriculum incorporate, if any?

d. How are didactics and scholarly activities structured into your curriculum?

• What are your curriculum’s weaknesses and strengths?

a. What changes are currently being made to your curriculum?

b. How has your program addressed potential low numbers for required clinical experiences, such as in obstetrics or inpatient pediatrics?

c. How did you promote stakeholder buy-in for the establishment of a rural family medicine residency program?

d. How did the health care professional community respond to the proposal of establishing a rural family medicine residency program?

• How did your program establish good partnerships with the neighboring hospitals or clinics?

• How is faculty retention?

a. What qualifications and educational training do you look for when hiring for faculty?

• How is resident retention?

a. What do the residents end up practicing or doing after graduation?

• Reflecting to the initial stages of your curriculum development, is there anything that you would do differently?

a. What advice would you give to an institutional who is thinking about or currently developing a rural family medicine residency program?

• Where do you think the future training of rural family medicine is heading?

a. How do you think ACGME requirements influence, or will influence, the training of rural family medicine residency programs?

|

Data Collection

The first author (L.F.) conducted all one-on-one, semistructured telephone interviews between June 2020 and July of 2020. Each interview lasted between 22 and 45 minutes, was audio recorded, and transcribed verbatim. L.F. wrote field notes after each interview to reflect on interviewees’ observations, growing insights, and how the student-outsider role may have informed the research process. Thematic saturation was evident when interviews yielded no new findings.

Data Analysis

We uploaded transcribed material into the qualitative data analysis software ATLAS.ti (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) and L.F. carried out abductive coding using content analysis with a directed content approach.28 We elected a directed approach to gain a richer understanding of employed strategies or best practices used by RFMRP program directors based on prior research.28, 29 In this study’s context we derived initial codes from existing theoretical frameworks and knowledge in RFMRP development, while allowing for additional data-driven codes to be generated from unanticipated observations (eg, interviewees’ advice and strategies used to overcome barriers).30, 31 L.F. then compared the transcripts to one another to develop broad, preliminary categories. We sought to establish trustworthiness in this qualitative research study by selecting relevant strategies for establishing rigor as recommend by Morse. 32 These included thick description, carefully developing a coding system, peer review debriefs, and paying attention to researcher bias through maintenance of a reflexive journal. Thus, our practice to demonstrate rigor involved biweekly peer review debriefs between L.F. and T.M., who refined categories into major themes and subthemes, and cross-verified mutual comprehension and application of codes. In addition, reflexive insights (eg, prior knowledge of residency development, researcher speculations about potential findings, etc) were considered and bracketed throughout all stages of the research process.33 Quinnipiac University’s Institutional Review Board judged this study to be exempt from federal regulations (protocol #04320).

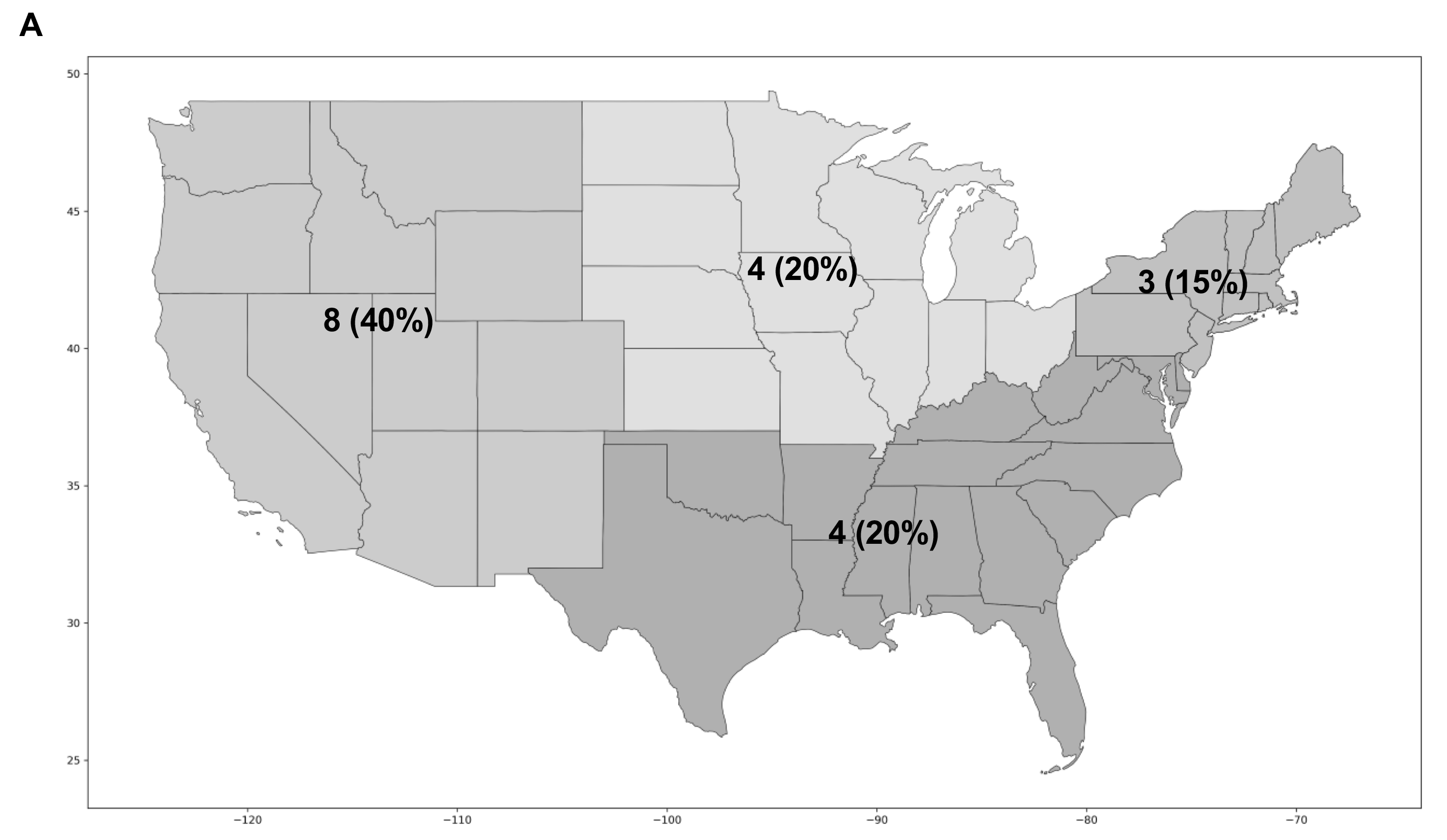

A total of 19 interviews were conducted with family medicine residency program directors—two identified as women and 17 identified as men. Interviewees encompassed all geographic areas in the United States with the Midwest representing 20%, the Northeast representing 15%, the South representing 20%, and the West representing 40% (Figure 1). We quantified program type and other key characteristics (Table 2). Community enrichment and evolving to meet demands were two major themes that best characterized the essence of a successful RFMRP. We identified and analyzed subthemes to better describe the multidimensional nature of the two major themes.

We identified five subthemes for the theme of, “community enrichment” (Table 3). Nearly all interviewees discussed the importance of community buy-in and its challenges. Having conversations at length with key stakeholders was identified to be critical for program development. An interviewee asserted it may “take a long time … like years … to convince people it is the right thing to do.” Community buy-in requires “… open communication, frequent re-communication with folks about what you are trying to do and what you are looking for.” A proper environmental scan to identify and assess local resources is also important. Common local resources identified that served as community assets were mental and behavioral health facilities, elementary schools/high schools, athletic teams, annual community events, and tribal health centers. Many interviewees believed that identified community assets should be prioritized in curricular design, as this will help developing programs differentiate themselves from other well-established programs and potentially be utilized as an effective recruitment strategy. One interviewee stated, “Your best strengths are going to be looking at what [resources are] already there.” In addition, many interviewees described their process of establishing clinical partnerships across great distances when key training resources were not available locally. Another subtheme we identified was to prioritize designing a robust continuity clinic. Advantages to designing a robust continuity clinic included bolstering family physician identity, enhancing residents’ clinical knowledge and skills, and delivery of high-quality care for community members. An interviewee stated, “I like having the clinic being our main priority … I think that is better for the patients.” Another interviewee added, “I think the residents learn more from clinic than they do from the rotations.” Cultivating or identifying a local physician champion was a common strategy to strengthen interviewees’ respective programs. One interviewee stated, “I think the most useful thing would be to have a local champion … more specifically a local family medicine physician who understands the lay of the land.” The idea of allocating resources to “grow your own” was identified as a common strategy for overcoming the lack of an existing local physician. Lastly, several interviewees proposed that adequately supporting faculty and physician preceptors was integral for program development. Many mentioned the challenging environment for faculty. An interviewee shared,

… we don’t have enough protected administrative time for faculty … So, a lot of it is just an add on with pretty marginal additional pay, or no additional pay, to what is already a busy, rural physician that takes a lot of call.

Many interviewees encouraged new and developing programs to seek out opportunities to provide faculty with adequate financial compensation.

We identified four subthemes for the theme of “evolving to meet demands” (Table 4). One common subtheme was to frequently revisit program mission to align with scope of family medicine. Interviewees encouraged new and existing rural residency programs to evaluate their mission, vision, and educational goals on an annual basis. Interviewees suggested that allocating the time and effort to outline program goals will help navigate developing programs through difficult decisions such has redefining or narrowing the scope of rural family medicine training. One interviewee shared their experience with this process:

… I do feel like our curriculum is based on an older model of training residents and I want to make sure that I am actually training residents for what they are going to go do, which is part of why I eliminated … one first year internal medicine rotation because I just looked at all of my graduates and none of them are doing high-level hospitalist work and I was like, ‘Wait a minute, why are we spending so much time in the hospital?’

On the contrary, some interviewees urged new and developing programs to develop a mission and program goals consistent with full-spectrum training:

It is up to residency programs to continue to push the envelope and stress the importance of full spectrum care because if you have ever practiced in a rural setting, you know that none of the specialists like to go out there and so, it makes no sense to restrict our family medicine training …

Many interviewees described the importance of defining and redefining expectations in medical education. Specifically, many interviewees discussed the importance of establishing firm boundaries with faculty and staff to prevent misunderstandings and “people taking advantage” of the program and residents. The integration of longitudinal experiences was identified among interviewees to be of value for it helps integrate clinical concepts for residents. Longitudinal experiences varied widely including but not limited to dermatology, health systems management, behavioral health, newborn nursery, and geriatrics. An interviewee shared it may be challenging to integrate longitudinal experiences into the curriculum, however:

I think we would have looked at longitudinal curriculum a little bit more. I think there may have been a way to build the rotations a little bit better if they weren’t always in blocks, but once the blocks were in place it would have taken a lot of work to switch back.

Finally, we identified innovation in curriculum design to be critical in program development. One interviewee stated,

The other thing is thinking outside of the box. So, you know, you need to do all these blocks and all these requirements, and we found that over time are a lot of different ways of meeting those requirements without necessarily having the rotations you would see at a bigger hospital.

Many interviewees identified creativity, flexibility, and dedication to education were necessary attributes for not only a program director to possess, but also critical qualities needed for innovative curricular design and transforming the landscape of family practice.

|

Rural Designation

|

n (%)

|

|

Rurally located

|

10 (53)

|

|

Integrated rural training track*

|

9 (47)

|

|

Type of Sponsoring Institution

|

n (%)

|

|

Academic medical center/medical school

|

6 (33.3)

|

|

General/teaching hospital

|

5 (27.8)

|

|

Community hospital

|

3 (16.7)

|

|

Federally qualified health center

|

2 (11.1)

|

|

Consortium

|

1 (5.6)

|

|

Other

|

1 (5.6)

|

|

Years Since Initial Accreditation

|

n (%)

|

|

Fewer than 5 years

|

6 (33)

|

|

5 to 10 years

|

7 (39)

|

|

More than 10 years

|

5 (28)

|

|

Size of Program

|

n (%)

|

|

Fewer than 10 residents

|

9 (50)

|

|

10 to 20 residents

|

7 (39)

|

|

Greater than 20 residents

|

2 (11)

|

|

Years as Program Director

|

n (%)

|

|

Fewer than 5 years

|

7 (39)

|

|

5 to 10 years

|

9 (50)

|

|

Greater than 10 years

|

2 (11)

|

|

Subtheme

|

Quote

|

|

Prioritize community buy-in

|

“I honestly think the community buy-in is going to be the most important. Having them on your side throughout the process is critical. Most curriculum you can kind of weave it in and out based on the requirements and what the local available resources are ... Here is a great example: We have an orthopedic group in town and at first, they were sort of lukewarm, didn’t want residents or anything. And we told our first class of residents, ‘Listen you guys are our ambassadors, you really got to make this work’. So, they did. After the very first rotation with that orthopedic group, they called me up and said, ‘We want more residents.’ So, having that level of buy-in is critical.” [Interviewee 3]

|

|

Evaluate local resources

|

“My advice would be to step back and look at your resources. And then … try to make a curriculum based on your resources, which is a little backwards. Usually, I think people do a curriculum and then try to find the resources to try to fulfill that curriculum. But I think in a rural area you have to look at your resources first and then design your curriculum based on what you have available.” [Interviewee 6]

|

|

Design a robust continuity clinic

|

“I think the thing we are in the midst of right now – which is doing the clinic first collaborative and the clinic first approach – is something I would start early. I think [our program], like many family medicine residencies, was kind of inpatient focused heavy. Meaning that we would often set up our inpatient rotations first, and sort of put outpatient experiences in and around the inpatient curriculum. So … it felt like the hospital was at the center and it really should be that the outpatient continuity clinic is at the center and that is where the essence of family medicine happens; that’s where you get to know your patients over time and take care of them in the context of their real, rural lives. So, I would encourage you to have a curriculum that is focused on outpatient continuity experiences first.” [Interviewee 8]

|

|

Cultivate or develop a local physician champion

|

“I think in my situation it really helped that I was from [this community] and had relationships, and I had to work to meet program director requirements, but I think that was a very positive thing … I think if somebody … dropped in that maybe looked better on paper as program director, then I don’t think [the program] would be as successful.” [Interviewee 13] “What we have had to do is we are trying to recruit a family practice physician that will check all the boxes … My hope is that we will be able to grow one on our own. That we will have a resident that comes through who likes OB, gets along with our Ob-Gyns, and … develop the relationship over the three years that our Ob-Gyns will look at them differently.” [Interviewee 1]

|

|

Adequately support faculty and physician preceptors

|

“One other thing that we do to support of our community of physicians … We give every preceptor who is a community preceptor or a volunteer preceptor, at the end of the year, just a certificate that says you have participated in the training of our family medicine residents for [insert hours] last year. They like that little token of appreciat[ion], but another cool thing about that is that a lot of CME certified lobbies like the AAFP will allow you to claim CME credit for teaching and that certificate gives them evidence that they taught, and hopefully with their boards can claim CME credit for it.” [Interviewee 3]

|

|

Subtheme

|

Quote

|

|

Frequently revisit mission to align with scope of family medicine

|

• “…Over time I would say the curriculum has evolved in that, now … it’s not that we train somebody to go out and do that full spectrum in a rural area, we provide training that allows somebody to go out and do what’s needed in a rural area … it really comes down to what is the true mission of your rural residency. I think that [your] mission statement … you’ve got to put a lot of hard thoughts into it. I tell you, we come back to it every year. ‘Is this still what we want to do? Train full spectrum?’ And over the years it’s come up, ‘Can we maintain the obstetrical piece? Can we maintain this level of inpatient experience?’” [Interviewee 17]

• “I think that… it is getting harder and harder to train primary care. To me, it is the most important group that we need to be training, but I have seen fewer and fewer medical students do it. And I think the breadth of what they are doing, what most rural programs are doing, including my own, is less and less compared to what I came out doing 27 years ago and what the residents now come out and do is just different because there is just a greater penetration of specialists, even in rural areas. So, it is harder to get training in operative obstetrics and procedural and inpatient medicine because there are people that just want to do that and, you know, what primary care is mostly outpatient and, you know, how do you balance between those two things? It is hard. I don’t know; it is an evolving process.” [Interviewee 11]

|

|

Redefine expectations in medical education

|

• “Your program director has to be pretty strong in setting up boundaries … I did have to hold the line pretty early in that, it is surprising how many physicians don’t know how medical education works, and administrators. The reason why I say that is, early on, you would have people who thought of them as cheap labor, and the focus has to be on education. There were a couple times early on, the hospital, you know, one of the administrators would come down and say, our pediatrics department is getting overwhelmed can I pull a couple of the residents out of their continuity clinic to go help out. Because all they look at is … at least they are seeing patients and I would have to say, absolutely not, this is their continuity clinic, they are required to be here and take care of their patients …” [Interviewee 1]

|

|

Integrate longitudinal experiences

|

• “… [when] my residents refer someone to counseling services or to psychiatry, it would be great if that resident could go to those appointments … because I think they would learn a lot from their own patient … or if the patient is getting a hip replacement surgery, the resident should maybe assist in that surgery so they could follow their patient. That takes scheduling, juggling sometimes. But I think that kind of stuff is more educational, sticks with you more.” [Interviewee 6]

• “We really rotate the weeks because… maybe to see a bit more of what family medicine looks like, right, because family medicine doesn’t do OB only on Mondays and then on Tuesdays all dermatology and then Wednesdays, you know, endocrinology. It is varied all the time. So, during the longitudinal weeks we have, just, a lot of things the residents do. Some of them scholarly, like they can lead journal club, they’ll have a day with orthopedics and then they will have two days of continuity clinic and then they will do neuropsychiatric testing or spend a day with the pharmacy doctor or spend the day with the behaviorist. And, of course, if there are resident preferences, you know, if a resident really wants to do c-sections, we will integrate c-section into their longitudinal weeks.” [Interviewee 4]

|

|

Be innovative in curriculum design

|

• “… this is your time to think about the ideal way to train family medicine physicians. So, when you do your curriculum try to make it the very best way that you can imagine training … I would say it is an exciting thing because you can use this as an opportunity to think outside the box, and do something new, and be innovative. So, don’t get trapped into thinking that you have to do it the same way every other place is doing it, because that’s not true. The ACGME has some rules, but there is also a lot of leeway in there to basically do and create what you want.” [Interviewee 16]

• “For example … if they are doing general surgery and the surgeon does scopes on Tuesday’s afternoons and they have seen two weeks of scopes and they really don’t need to see anymore then we will pull them back to clinic.” [Interviewee 7]

• “We have been able to develop a pretty strong global health experience … where we have been able to send 1-2 teams a year … typically each team is 2 residents and a faculty, and they spend a month in [a rural area in Africa] working on inpatient adult medicine and inpatient pediatric medicine, primarily. So, we count those numbers towards the ACGME requirements. So far that’s how I have tried to get around that challenge.” [Interviewee 17]

|

RFMRPs have demonstrated success in training graduates to practice rural family medicine; yet, there is a dearth of first-hand accounts and reports of best practices from program directors that would assist institutions with the development of a sustainable rural residency program. Prior studies have focused on IRTT infrastructure sustainability, identifying IRTT challenges and resilience factors crucial for avoiding closure.19, 34, 35, 36 This is the first qualitative study to identify and describe common strategies implemented by program directors of RFMRPs across the nation to strengthen rural residency program development.

Our study identified community enrichment and evolving to meet demands to be two major themes that best characterized the essence of a successful RFMRP. Community enrichment includes prioritizing community buy-in and a proper evaluation of local resources. We also identified the ambulatory clinic to be a critical aspect of the RFMRP experience as it promotes resident training and strengthens professional identify formation. Cultivating or developing a local physician champion while adequately supporting faculty was found to be integral to a successful RFMRP. Evolving to meet demands included the need to frequently revisit program mission to align with scope of family medicine, the ability to define boundaries in medical education, effectively integrating longitudinal experiences, and exercising creativity and innovation.

Our study corroborates findings reported in the literature that identifying community assets is essential in preliminary residency developmental stages.15, 23 Previous reports state community assessments are important to identify interested parties, document clinical capacity, and evaluate physical resources.15, 23 Our data highlight that capitalizing on community strengths may be instrumental for developing a unique curriculum that focuses on community needs, such as facilities or community programs dedicated towards global health, street medicine, and addiction medicine, among other examples.

Our findings illustrate the importance of developing the ambulatory clinic as the focal point of the RFMRP experience, which supports the utility of the Clinic First Collaborative approach.37 Clinic First is a paradigm that aims to improve ambulatory residency training and experience for residents and patients.37 The effectiveness of this paradigm is currently under study. However, no study to date has specifically linked the Clinic First approach to RFMRPs graduate outcome metrics. A recent survey found that 68% of family medicine residency directors state their ideal curriculum is the Clinic First model yet, only 27% actually practiced the model, suggesting a delay in curricular implementation.38 Barriers, such as lack of paradigm understanding, lack of institutional support, or scheduling challenges have been documented.38 Ultimately, the Clinic First Collaborative shows potential but its impact in a rural setting warrants further investigation.

Interestingly, many of our interviewees highlighted the value of embedding longitudinal experiences into the curriculum. Literature on the outcomes of longitudinal experiences in residency programs are lacking although a few studies have shown promising data.39, 40, 41 One study reported that resident participation in a longitudinal elective significantly influenced their growth in day-to-day clinical experiences, learning ability, and freedom to explore areas of interest in more detail.39 Another study found that a longitudinal quality improvement experience improved family medicine resident quality improvement competency and increased scholarship and leadership expereience.40 Although initial studies are promising, further research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of longitudinal curricula in RFMRPs.

Many interviewees commented on the changing scope of rural family medicine, including the vulnerability of full-spectrum care and how some RFMRPs may be shifting to a “learn as you will practice” paradigm to address specific local or regional population health care needs. This narrower scope of practice for family physicians may have a negative impact on patient health outcomes in a rural setting.1, 5 A cross-sectional study that studied 13,884 family physicians taking the American Board of Family Medicine Maintenance of Certification for Family Medicine Examination found a significant decrease in intent to practice full-spectrum care in recertifying practitioners compared to graduating residents. Most notably, there was a significant decrease in intent to practice in several key areas, including prenatal care (50.2% vs 9.9%), home visits (44.1% vs 9.3%), inpatient care (54.9% vs 33.5%), and obstetric care (23.7 vs 7.7%).42 Studies indicate the underlying reasons for the change in a narrower scope are multifactorial, such as the national and regional health care demands, practice setting, local demographics and cultural norms, personal preferences, and more.43, 44 Narrowing the scope of family practice may have serious consequences on population health as greater continuity of care has been associated with lower mortality45 and lower rates of patient hospitalizations and health care costs.46 There is a need for further research into identifying and devising solutions to address health disparities attributed to change in rural family medicine practice scope.

Limitations of this study include its relatively small convenience sample of program directors from RFMRPs, though our sample size achieved thematic saturation. In addition, a limitation of using a qualitative study design is the generalizability of our findings. However, our primary goal was to enhance the contextualized understanding of RFMRP development through program directors’ perspective. Interviewer bias may have subconsciously influenced the responses from the interviewees. To mitigate interviewer bias, we carried out critical reflexivity at every stage of the research process.33

In conclusion, community enrichment and the ability for residency programs to evolve to meet demands are important components to a successful RFMRP. Developing RFMRPs may benefit by evaluating one’s local resources, prioritizing community buy-in, designing a robust continuity clinic, identifying and cultivating a local physician champion, and supporting the community of faculty and physicians. Additionally, frequently revisiting one’s program’s mission to align with the scope of family medicine, redefining expectations in medical education, integrating longitudinal experiences, and implementing innovation in curriculum design are potential strategies to help RFMRPs evolve to meet GME demands. Future research can explore the advantages and consequences of a narrower scope of practice for family physicians or interview residents to gain the unique perspective of a trainee. Our findings help identify best practices for developing RFMRPs and highlight strategies utilized by current programs to help meet the needs of the changing landscape of rural family medicine GME.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ingrid Philibert, PhD, MA, MBA, senior director, accreditation, evaluation and scholarship at the Frank H. Netter MD School of Medicine, for her support and review of this manuscript. The authors honor and acknowledge the original caretakers and traditional village sites our medical institution occupies. The Frank H. Netter MD School of Medicine acknowledges the Quinnipiac, Wappinger, Hammonasset, Mohegan, Mashantucket Pequot, Eastern Pequot, Schaghticoke, Golden Hill Paugussett, Niantic, and Nipmuck nations.

Presentations

The results of this study were presented at the following conferences:

-

Biomedical Research Symposium (virtual poster), November 4, 2020.

-

Netter Summer Research Poster Day (virtual poster), October 23, 2020.

Funding Sources

This project was supported by the Summer Research Fellowship, Frank H. Netter MD School of Medicine.

References

2. McGrail MR, Wingrove PM, Petterson SM, Bazemore AW. Mobility of US rural primary care physicians during 2000-2014. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(4):322-328. doi:10.1370/afm.2096

5. Meyers P, Wilkinson E, Petterson S, et al. Rural Workforce Years: Quantifying the Rural Workforce Contribution of Family Medicine Residency Graduates. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(6):717-726. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-20-00122.1

7. McGrail MR, O’Sullivan BG, Russell DJ. Rural training pathways: the return rate of doctors to work in the same region as their basic medical training. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1):56. doi:10.1186/s12960-018-0323-7

9. Rodgers DV, Wendling AL, Saba GW, Mahoney MR, Brown Speights JS. Preparing family physicians to care for underserved populations: a historical perspective. Fam Med. 2017;49(4):304-310.

11. Longenecker RL, Andrilla CHA, Jopson AD, et al. Pipelines to pathways: medical school commitment to producing a rural workforce. J Rural Health. 2021;37(4):723-733. doi:10.1111/jrh.12542

15. Hawes EM, Weidner A, Page C, et al. A Roadmap to rural residency program development. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(4):384-387. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-19-00932.1

16. Damos JR, Sanner LA, Christman C, Aronson J, Larson S. A process for developing a rural training track. Fam Med. 1998;30(2):94-99.

17. Catinella AP, Magill MK, Thiese SM, Turner D, Elison GT, Baden DJ. The Utah rural residency study: a blueprint for evaluating potential sites for development of a 4-4-4 family practice residency program in a rural community. J Rural Health. 2003;19(2):190-198. doi:10.1111/j.1748-0361.2003.tb00561.x

18. Rourke JT. Postgraduate training for rural family practice. Goals and opportunities. Can Fam Physician. 1996;42:1133-1138.

19. Patterson DG, Schmitz D, Longenecker RL. Family Medicine Rural Training Track Residencies: risks and Resilience. Fam Med. 2019;51(8):649-656. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.769343

20. Lypson M, Simpson D. It all starts and ends with the program director. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):261-263. doi:10.4300/JGME-03-02-33

21. Maudlin RK, Newkirk GR. Family Medicine Spokane Rural Training Track: 24 years of rural-based graduate medical education. Fam Med. 2010;42(10):723-728.

22. Nash LR, Shepherd AJ, Caskey JW, Cass AR. Development of a rural training track for Texas. Tex Med. 2002;98(8):45-50.

23. Liskowich S, Walker K, Beatty N, Kapusta P, McKay S, Ramsden VR. Rural family medicine training site: proposed framework. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61(7):e324-e330.

24. Stearns JA, Stearns MA, Glasser M, Londo RA. Illinois RMED: a comprehensive program to improve the supply of rural family physicians. Fam Med. 2000;32(1):17-21.

27. Kallio H, Pietilä AM, Johnson M, Kangasniemi M. Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(12):2954-2965. doi:10.1111/jan.13031

28. Kibiswa, N . 2019. Directed qualitative content analysis (DQlCA): a tool for conflict analysis.

29. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

31. Coffey AJ, Atkinson PA. Making Sense of Qualitative Data. SAGE Publications; 2021.

32. Morse JM. Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(9):1212-1222. doi:10.1177/1049732315588501

33. Polit DF, Beck CT. Essentials of Nursing Research: Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice. Vol 7. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

35. Eidson-Ton WS, Rainwater J, Hilty D, et al. Training medical students for rural, underserved areas: a rural medical education program in California. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(4):1674-1688. doi:10.1353/hpu.2016.0155

36. Bush RW, LeBlond RF, Ficalora RD. Establishing the first residency program in a new sponsoring institution: addressing regional physician workforce needs. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(5):655-661. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-15-00749.1

37. Gupta R, Barnes K, Bodenheimer T. Clinic first: 6 actions to transform ambulatory residency training. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(4):500-503. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-15-00398.1

38. Zeller TA, Ewing JA, Asif IM. Prevalence of clinic first curricula: a survey of AFMRD members. Fam Med. 2019;51(4):338-343. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.666943

39. Millstein LS, Feigelman S, Custer JW, Giudice EL. Individualisation of resident education through pathways and longitudinal experiences. Med Educ. 2019;53(5):506-507. doi:10.1111/medu.13876

40. Pohl SD, Van Hala S, Ose D, Tingey B, Leiser JP. A Longitudinal curriculum for quality improvement, leadership experience, and scholarship in a family medicine residency program. Fam Med. 2020;52(8):570-575. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.679626

41. Simasek M, Ballard SL, Phelps P, et al. Meeting resident scholarly activity requirements through a longitudinal quality improvement curriculum. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(1):86-90. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-14-00360.1

42. Coutinho AJ, Cochrane A, Stelter K, Phillips RL Jr, Peterson LE. Comparison of intended scope of practice for family medicine residents with reported scope of practice among practicing family physicians. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2364-2372. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.13734

43. Russell A, Fromewick J, Macdonald B, et al. Drivers of scope of practice in family medicine: a conceptual model. Ann Fam Med. 2021;19(3):217-223. doi:10.1370/afm.2669

44. Reitz R, Horst K, Davenport M, Klemmetsen S, Clark M. Factors influencing family physician scope of practice: a grounded theory study. Fam Med. 2018;50(4):269-274. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.602663

45. Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Phillips RL, Bitton A, Landon BE, Phillips RS. Association of primary care physician supply with population mortality in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(4):506-514. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7624

46. Bazemore A, Petterson S, Peterson LE, Phillips RL Jr. More comprehensive care among family physicians is associated with lower costs and fewer hospitalizations. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(3):206-213. doi:10.1370/afm.1787

There are no comments for this article.