Background and Objectives: Burnout is considered a public health crisis among physicians and is related to poor quality of life, increased medical errors, and lower patient satisfaction. A recent literature review and conceptual model suggest that awareness of life meaning, or meaning salience, is related to improved stress and coping, and may also reduce experience of burnout. This study examined associations among meaning salience, burnout, fatigue, and quality of life among family medicine residency program directors.

Methods: Data were collected via an online survey administered by the Council of Academic Family Medicine (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA; n=268, response rate of 45.4%) in December 2018. Program directors completed measures of meaning salience, burnout, fatigue, and quality of life. Data were analyzed using Spearman correlations and path analysis.

Results: Program directors who reported greater experienced meaning salience also reported significantly less burnout (β=-.40, P<.001) and less fatigue (β=-.38, P<.001), which were then both significantly associated with greater quality of life (Ps<.001). Program directors who reported greater meaning salience also reported greater quality of life (β=.21, P<.001). Additionally, there were significant indirect associations between meaning salience and quality of life through less burnout and fatigue (β=.26, P<.001).

Conclusions: The potential for increasing physicians’ awareness of their sense of meaning as a means to prevent or decrease burnout is underresearched and warrants further study. Both preventive measures (eg, wellness curricula) and interventions with already-distressed physicians may encourage regular reflection on meaning in life, especially during busy workdays.

Burnout, characterized as a syndrome of emotional exhaustion and cynicism as a consequence of prolonged stress and anxiety at work, is a significant problem among physicians.1 Research showing about half of all physicians experience some burnout has contributed to it being labeled a public health crisis.2-3 Family physicians in particular have been shown to have a 40% higher risk of burnout than the average physician.3 The work conditions of family physicians, including considerable time pressures, perceptions of chaotic work environments, and low control over their work, may contribute to increased burnout, which in turn may lead to reduced job satisfaction and greater perceived job stress.4

Program directors of family medicine residency programs may be at a particular risk for burnout given their myriad responsibilities. In addition to seeing their own patients in clinic, program directors have considerable job responsibilities of overseeing a residency program in which they may (a) supervise other faculty physicians, (b) manage logistics and schedules of faculty and residents, (c) handle personnel issues among residents and faculty, (d) drive innovations and program changes, and (e) have academic research responsibilities, including writing grants and manuscripts and reviewing scholarly work. In turn, burnout could affect the quality of life of these program directors, and ultimately the program as a whole. Evidence suggests that burnout is related to job turnover in medical residency program directors,5 and frequent turnover in this important role can have ripple effects on the entire program.

Although there is limited evidence on the consequences of burnout in family medicine program directors, the consequences of physician burnout are well documented. Specifically, physicians who experience greater burnout also report increased susceptibility to depression, suicidal ideation, interpersonal conflicts, fatigue, and poor quality of life.1,6 Further, in a systematic review of 47 studies examining burnout in physicians, physicians who experienced greater burnout were at an increased risk of patient safety incidents, poorer quality of care due to low professionalism, and reduced patient satisfaction.7 Given these serious consequences of burnout, universities and health systems are developing programs to promote wellness and mitigate burnout among physicians.8

One potentially important factor that has received minimal attention in the burnout literature is a sense of meaning in life. Recently, Hooker, Masters, and Park9 reviewed the literature and created a conceptual model hypothesizing how a sense of meaning in life may influence greater well-being. In particular, they hypothesized that meaning in life may influence health and well-being through three pathways: (a) reduced experience of stress, (b) more adaptive coping skills, and (c) greater engagement in health behaviors. As burnout is a state of exhaustion caused by prolonged stress, those who experience greater meaning may experience stressful events as less stressful and they may employ better coping strategies to handle those events; therefore, they would experience less burnout and fatigue caused by stress. Research has supported this hypothesis showing that a greater sense of meaning in life is associated with reduced stress,10,11 improved coping skills,12,13 and better psychological health and functioning, including greater quality of life and less fatigue.14,15

A key question is how a sense of meaning in life translates into reduced stress and improved coping. Hooker et al9 suggest that maintaining awareness of what makes one’s life meaningful at any given moment, or a sense of “meaning salience,”16 may be key for translating a global sense of meaning into daily experience and behavioral self-regulation. For program directors, this may be a greater awareness of why they chose professions as family physicians throughout busy days (eg, choosing family medicine to help people improve their health) in coping with more stressful days and their demanding jobs. For example, physicians who regularly reflect upon their dedication to helping patients effectively manage illness may be better equipped psychologically to cope with the everyday stressors of documentation, unpredictable schedules, and long hours. More specifically for program directors, focusing on training the next generation of family physicians may give them meaning in their work, and therefore make it less stressful when they have to work with struggling residents. With reduced experience of stress, program directors would be likely to experience less burnout and less fatigue, which would improve their overall quality of life. However, this pathway has not yet been tested. Thus, better understanding the associations among meaning salience, burnout, and well-being among program directors may shed light into novel approaches to burnout prevention among this group and family physicians as a whole.

The objectives of this study were (1) to examine the associations among meaning salience, burnout, fatigue, and quality of life among program directors of family medicine residency programs, and (2) to test whether there are indirect associations between meaning in life and quality of life through burnout and fatigue. We hypothesized that greater meaning salience would be associated with greater quality of life directly, and that meaning salience would be associated quality of life indirectly through less burnout and fatigue.

Participants and Procedure

Questions were part of a larger omnibus survey conducted by the Council of Academic Family Medicine (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA). The methodology of the CERA Program Director Survey has previously been described in detail.17 The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved the project in November 2018. Data was collected from December 2018 to January 2019.

The sampling frame was all ACGME-accredited US family medicine residency program directors as identified by the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors (AFMRD). Email invitations were delivered with Survey Monkey. We sent seven follow-up emails to encourage nonrespondents to participate. There were 624 program directors at the time of the survey; as 16 had previously opted out of CERA surveys and 18 emails could not be delivered, the final sample size was 590. The overall response rate for the survey was 45.4% (268/590).

Measures

In addition to general demographic items that were part of the larger survey (ie, gender, race/ethnicity, length of time as a program director), this study addressed four domains with 14 questions (questions are available in the Appendix at https://journals.stfm.org/media/2754/appendix-hooker.pdf).

Meaning Salience. The 10-item Thoughts of Meaning Scale16 measured daily meaning salience (eg, “How much have you thought about what makes your life meaningful today?”). Participants rated the items on 7-point Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (absolutely or quite a bit). Items were summed for a total score; higher scores corresponded to greater meaning salience. Previous research has indicated that the scale demonstrates internal consistency and is positively associated with other measures of meaning and purpose in life.12 The internal consistency of the scale was high (a=.89).

Burnout. Two items from the Maslach Burnout Inventory assessed emotional exhaustion (“feeling burned out”) and depersonalization (being “more callous toward people”) in participants’ roles as program director. Both items were on a 7-point Likert-type scale assessing frequency. Items were summed for a total score, with higher scores corresponding to greater burnout. Research has shown that these two items provide meaningful stratification of risk of high burnout among medical professionals.18

Fatigue. The one item assessing fatigue is an adaptation of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) measure on fatigue19; participants rated their fatigue level “today” rather than past week. The time frame was chosen to match the time frame in the meaning salience measure. Participants rated their fatigue on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

Quality of Life. The one item assessing overall quality of life came from the PROMIS global health scale.20 Participants rated their quality of life on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent).

Data Analysis

We conducted analyses using SAS 9.421 and Mplus 8.1.22 We used bivariate Spearman correlations to examine relationships among continuous variables. Path analysis, using robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimation, examined a multiple mediator model assessing the associations among meaning salience, burnout, fatigue, and quality of life, and to test whether there were indirect associations between meaning salience and quality of life through burnout and fatigue. We chose path analysis as the statistical method because it simultaneously estimates multiple linear regression models, allowing for multiple independent and dependent variables, and it can estimate variance due to direct and indirect (mediation) effects. We allowed burnout and fatigue to correlate in the model as it was hypothesized that greater burnout would be associated with greater fatigue. MLR estimation is robust to nonnormality, which may occur with ordinal Likert-type scale variables. The model controlled for gender (male [1] vs female [0]), race/ethnicity (white [1] vs nonwhite [0]), and length of time as a program director. Specifically, direct paths were added so that (a) burnout regressed on gender; (b) fatigue regressed on gender; and (c) quality of life regressed on gender, race/ethnicity, and length of time as a program director. Furthermore, the model included cases with partially complete data using full information robust maximum likelihood estimation. We assessed model fit using several fit indices: a nonsignificant χ2, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)<.06, comparative fit index (CFI)>.95, and standardized root mean residual (SRMR)<.08.23

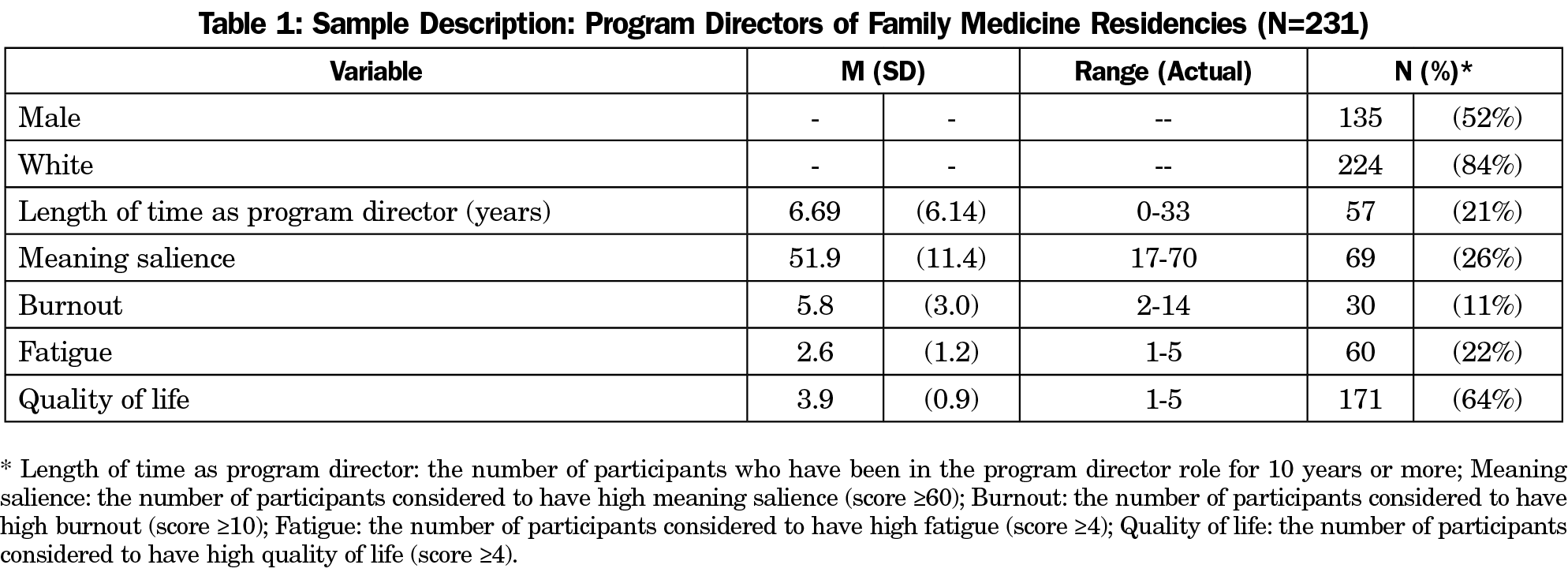

A total of 231 program directors who answered questions about meaning salience were included in the analyses (48% female, 84% white). This represented a survey response rate of 39%. Sample descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. The majority of respondents had been in the program director role for less than 10 years (79%). Further, program directors reported low levels of burnout (89%), fatigue (78%), and meaning salience (74%). Nearly two-thirds of program directors reported high quality of life (64%; see Table 1 notes for specifics on how the scores were categorized).

Table 2 shows correlations among the study variables. In the bivariate analyses, meaning salience was significantly and negatively associated with burnout and fatigue, and positively associated with quality of life. Program directors who were more aware of their meaning during the day experienced less burnout and fatigue and greater quality of life. Burnout and fatigue were significantly and negatively associated with quality of life; program directors who experienced greater burnout and fatigue also experienced reduced quality of life. Burnout and fatigue were moderately and positively correlated; program directors who reported greater burnout also reported experiencing more fatigue. Women reported greater burnout and fatigue than men; however, there were no sex differences in quality of life or meaning salience. Program directors with longer tenures reported greater quality of life and less fatigue.

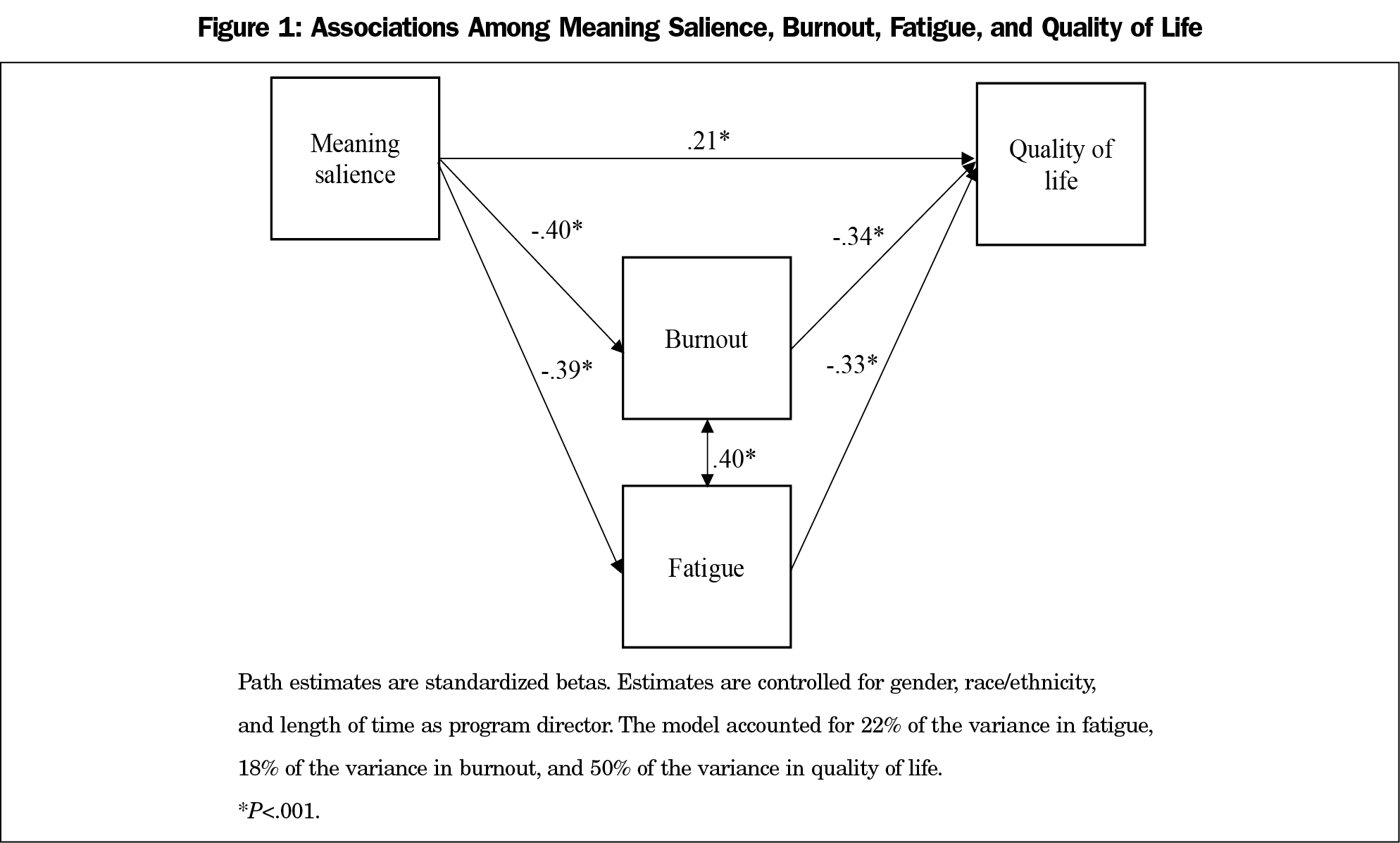

The overall path analysis model adequately fit the data (χ2 [4]=8.33, P=.08; RMSEA=.06 [90% CI=.00, 13]; CFI=.99; SRMR=.03; see Figure 1). Covariates were not included in the model for visual simplicity. As hypothesized, greater experienced meaning salience was significantly associated with both less burnout and less fatigue, which were then both significantly associated with greater quality of life. Program directors who reported more awareness of meaning during the day also experienced less burnout and less fatigue and greater quality of life. In addition to the significant, direct, and positive association between meaning salience and quality of life, there were significant indirect associations between meaning salience and quality of life through burnout (β=.14, P<.001) and fatigue (β=.13, P<.001). The total indirect effect of meaning salience on quality of life through burnout and fatigue was significant (β=.26, P<.001) and the total effects (both direct and indirect) of meaning salience on quality of life were moderate and significant (β=.47, P<.001). Thus, program directors who were more aware of what made their lives meaningful during the day experienced less burnout and less fatigue, which indirectly was related to greater quality of life. Being more aware of meaning during the day was also directly related to greater quality of life. For every standard deviation increase in meaning salience, quality of life increased by nearly half a standard deviation. The model accounted for 22% of the variance in fatigue, 18% of the variance in burnout, and 50% of the variance in quality of life.

As hypothesized, program directors who were more aware of what makes their life meaningful reported lower levels of burnout and fatigue and greater quality of life. Furthermore, program directors who experienced greater meaning salience indirectly experienced greater quality of life through less burnout and fatigue. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine meaning in life in relation to burnout among family medicine program directors. These results are consistent with previous studies that have found meaning in life to be associated with less burnout in other professions (ie, firefighters) and to be associated with better overall psychological health and functioning.14,15,24 Our findings support previous hypotheses that being aware of one’s sense of meaning could be helpful for reducing stress.9

Program directors in this sample reported lower levels of burnout (11%) compared to another study of practicing physicians (38%).3 This is consistent with a review of the burnout literature that found that physicians in academic or other practices have lower rates of burnout compared to physicians in private practice.25 The roles of family medicine program directors are very different than those of practicing family physicians not in academic settings who primarily conduct clinical care. Program directors have leadership roles in an academic setting, which require them to handle the daily stressors of running a residency program, including managing busy schedules, handling personnel issues, and dividing their time among academic, administrative, and clinical roles. It may be that having more autonomy and control as a program director is helpful for coping with job stress.25 It may also be that those who are able to handle the variety of responsibilities and the leadership role self-select into the role of a program director, and they were better able to handle stress than some of their peers.

Regardless, results of this study suggest that program directors who are able to refocus their attention on what makes their life meaningful, or who are aware of how their job contributes to their meaning throughout the day, may be better equipped to cope with those stressors. Although research on meaning, stress, and burnout is limited among physicians, evidence from other participant populations offers some support. Specifically, participants in laboratory stress studies with a greater sense of meaning demonstrate reduced cardiovascular reactivity (heart rate variability) in response to stress.26 Further, individuals who track their meaning over several days (effectively pausing and reflecting on meaning) and experience an increase in daily meaning are more likely to use proactive coping strategies (planning to cope with future events).13 These previous studies suggest that those who experience greater meaning are experiencing less stress and are more likely to employ adaptive coping strategies to manage stress as it arises. These studies support the notion that meaning salience is beneficial for coping with stress, and therefore could reduce experience of burnout or fatigue and improve quality of life.

Identifying factors related to less burnout and fatigue could be helpful in improving wellness among program directors and, more broadly, among physicians. We surmise that many physicians chose medicine as a career with aspirations of curing disease, partnering with patients, and improving overall health. Indeed, physicians who believe their work is personally meaningful and have a prosocial purpose experience less burnout.27 Program directors may have the added sense of meaning of training the next generation of family physicians who will care for the health and well-being of the population. However, program directors and physicians can easily lose sight of the meaning in work when overwhelmed by the many demands associated with the current practice of medicine; for example, practicing physicians devote approximately half of their time to working in the electronic medical record.28,29 In the current study, many program directors reported low levels of meaning salience, suggesting this domain might benefit from intervention. Preventive measures (eg, wellness curricula) and interventions with already distressed physicians may teach exercises that physicians can incorporate in their busy schedules to encourage regular reflection on sense of meaning as a physician. One example may be encouraging purposeful reflection during a busy work day, such as in the middle of the clinic day or in a day of meetings, when the program director or physician can pause for 1-2 minutes to reflect on what is meaningful or important to them. This type of intervention may recharge the person’s ability to cope with stressors and therefore reduce the likelihood of burnout or fatigue. Alternatively, sending physicians occasional messages (such as a text message) reminding them of what they said gives their life and work meaning may encourage more reflection and resilience. Finding ways to help program directors and physicians cope with the stressors of their job is key to reducing burnout, and ultimately depression, suicidal ideation, interpersonal conflicts, fatigue, and poor quality of life.1,6

This study is limited by the cross-sectional study design, which means that cause and effect cannot be inferred. In addition, measures of burnout, fatigue, and quality of life were obtained through 1- or 2-item scales, which may reduce the reliability and variance of those constructs compared to longer measures. Also, these results cannot be generalized to physicians in other specialties or roles. However, this study is strengthened by the use of a large, national sample of family medicine residency directors.

This study provides initial evidence that greater meaning salience is related to less burnout and fatigue and greater well-being among family physicians. Future studies should use samples of physicians from other specialties and roles (not just program directors). Both daily diary studies of burnout and meaning and evaluation of interventions that increase meaning salience among physicians would be interesting next steps.

References

- Rothenberger DA. Physician burnout and well-being: A systematic review and framework for action. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(6):567-576. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000844

- Jha A, Iliff A, Chaoi A et al. A crisis in healthcare: A call to action on physician burnout. Harvard Global Health Institute. http://www.massmed.org/News-and-Publications/MMS-News-Releases/Physician-Burnout-Report-2018/. Published 2018. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199

- Rabatin J, Williams E, Baier Manwell L, Schwartz MD, Brown RL, Linzer M. Predictors and outcomes of burnout in primary care physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(1):41-43. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150131915607799

- O’Connor AB, Halvorsen AJ, Cmar JM, et al. Internal medicine residency program director burnout and program director turnover: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2019;132(2):252-261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.10.020

- Tawfik DS, Profit J, Morgenthaler TI, et al. Physician burnout, well-being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(11):1571-1580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.05.014

- Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-1330. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713

- Ripp JA, Privitera MR, West CP, et al. Well-being in graduate medical education: A call for action. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):914-917. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001735

- Hooker SA, Masters KS, Park CL. A meaningful life is a healthy life: A conceptual model linking meaning and meaning salience to health. Rev Gen Psychol. 2018;22(1):11-24. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000115

- Burrow AL, Hill PL. Derailed by diversity? Purpose buffers the relationship between ethnic composition on trains and passenger negative mood. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2013;39(12):1610-1619. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213499377

- Zilioli S, Slatcher RB, Ong AD, Gruenewald TL. Purpose in life predicts allostatic load ten years later. J Psychosom Res. 2015;79(5):451-457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.09.013

- Smith BW, Zautra AJ. Purpose in life and coping with knee-replacement surgery. Occup Ther J Res. 2000;20(1_suppl):96S-99S. https://doi.org/10.1177/15394492000200S109

- Miao M, Zheng L, Gan Y. Meaning in life promotes proactive coping via positive affect: A daily diary study. J Happiness Stud. 2017;18(6):1683-1696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9791-4

- Low G, Molzahn AE. Predictors of quality of life in old age: a cross-validation study. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30(2):141-150. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20178

- Thompson P. The relationship of fatigue and meaning in life in breast cancer survivors. Onc Nurs Forum 2007;34(3):653-660. https://doi.org/10.1188/07.ONF.653-660

- Hooker SA, Masters KS. Daily meaning salience and physical activity in previously inactive exercise initiates. Health Psychol. 2018;37(4):344-354. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000599

- Mainous AG III, Seehusen D, Shokar N. CAFM Educational Research Alliance (CERA) 2011 Residency Director survey: background, methods, and respondent characteristics. Fam Med. 2012;44(10):691-693.

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Single item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization are useful for assessing burnout in medical professionals. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(12):1318-1321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1129-z

- Lai JS, Cella D, Choi S, et al. How item banks and their application can influence measurement practice in rehabilitation medicine: a PROMIS fatigue item bank example. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(10)(suppl):S20-S27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.08.033

- Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, et al; PROMIS Cooperative Group. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Med Care. 2007;45(5)(suppl 1):S22-S31. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04

- SAS Institute, Inc. The SAS System for Windows (Version 9.4). [Computer software] Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 2015.

- Muthén B, Muthén L. Mplus version 8 [Computer software]. 2018.

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6(1):1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Krok D. Can meaning buffer work pressure? An exploratory study on styles of meaning in life and burnout in firefighters. Arch Psychiatry Psychother. 2016;1(1):31-42. https://doi.org/10.12740/APP/62154

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516-529. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12752

- Ishida R, Okada M. Effects of a firm purpose in life on anxiety and sympathetic nervous activity caused by emotional stress: assessment by psycho-physiological method. Stress Health. 2006;22(4):275-281. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1095

- Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(3):415-422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.11.012

- Rosenthal DI, Verghese A. Meaning and the nature of physicians’ work. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1813-1815. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1609055

- Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: A time and motion study in 4 Specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(11):753-760. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-0961

There are no comments for this article.