Background and Objectives: A recognized gap exists between primary care physicians’ training in musculoskeletal (MSK) medicine and the burden of MSK complaints in primary care. Family medicine interns often lack adequate baseline MSK physical exam skills, which prompted a proposal to introduce a fourth-year preceptorship to reinforce MSK education. The aim of this study was to prioritize the most important elements to include in this new clinical rotation.

Methods: We employed a three-round, modified Delphi method to derive consensus. Eleven panelists with experience and expertise in MSK training, medical education, or both generated a list of 118 elements. Each panelist then ranked each element by level of importance, and we reviewed the results. The ranking process was repeated two more times with a goal of achieving consensus.

Results: Seventy-seven curricular elements (topics, skills, experiences) achieved consensus recommendation by being ranked either “fairly important” or “very important” for inclusion in the curriculum. Twenty-eight items were unanimously ranked “very important,” 42 received a mix of “very important” and “fairly important” rankings, and seven received unanimous ranking of “fairly important.” Three items were unanimously ranked “neither important nor unimportant.”

Conclusions: Longitudinal repetition of physical exam skills, reinforcement of relevant anatomy, and incorporation of specific frameworks for approaching MSK care are important components. Physical examination of the shoulder, knee, back, and hip are especially meaningful clinically.

A widely recognized mismatch exists between the burden of musculoskeletal (MSK) concerns in the primary care setting and the adequacy of training provided to primary care physicians to manage those concerns. 1-5 A recent Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance study suggested that most family medicine interns begin residency with inadequate MSK physical exam skills, 6 a finding consistent with previous reports that 80% of medical school graduates were deficient in basic MSK medicine. 7 Preclinical MSK education does not improve MSK knowledge assessed at the time of graduation, 8 but primary care MSK rotations can be as effective as orthopedic rotations for training emergency medicine residents. 9 A fourth-year MSK rotation might increase medical school graduates’ competence.

Competency-based training10, 11 requires recurrent, meaningful experiences. The American Medical Society for Sports Medicine has reimagined MSK training in undergraduate medical education (UME), focusing on domains of competence and entrustable professional activities (EPAs). 12 MSK education should be longitudinal, emphasizing basic exam skills in preclinical years with additional sports medicine training in years three and four. 13 To address clinical deficiencies, clinical training opportunities can be redesigned, 14 and outpatient exposure alone can improve trainees’ confidence and willingness to provide care. 15 Inspired by the flexible curriculum outline for family medicine subinternships,16 this study aimed to identify the elements of a meaningful educational experience in MSK medicine for fourth-year medical students.

The Delphi technique is an established method to derive consensus, and modified methods have been used previously in curricular development. 17-19 We employed the modified technique of three rounds, foregoing statistical stability analysis and aiming to achieve consensus regarding which elements should be included in a fourth-year medical student MSK course.

A group within the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Musculoskeletal and Sports Medicine Education Collaborative identified and invited panelists based on prior involvement in scholarly work on similar topics, academic reputation, and experience with curriculum development. Recruitment was by direct invitation from the lead author. A description of the panel’s composition appears in Table 1.

|

Total panelists

|

11

|

|

Gender (self-identified)

|

7 male, 4 female

|

|

Number with certificate of added qualification in sports medicine

|

8 (and 1 in fellowship)

|

|

Nonsports trained participants

|

2

|

|

Reasons for recruitment

|

• Prior contributions to national family medicine curriculum design

• National involvement in medical student education

|

|

Family medicine clerkship faculty

|

8

|

|

Teaching responsibilities

|

All involved in teaching at one or more of the following levels:

• Preclinical education

• Core family medicine clerkship

• Fourth-year family medicine rotations

• Sports medicine electives (medical student and resident levels)

|

We solicited ideas by telephone and email communication (see online Appendix for outreach email) for components and learning objectives of a meaningful fourth-year elective. The lead author coded these responses and identified latent themes to organize the elements. 20, 21 Themes with sorted elements were submitted for member checking, 22 and the participants confirmed the following categories prior to beginning the Delphi ranking: scheduling, learning objectives, technical skills, and clinical entities. The institutional review board deemed approval for this study unnecessary.

An initial list of 103 items was submitted to the panelists via electronic survey. The panelists were instructed to “rate the importance of incorporating each item into the elective” using a 5-point Likert scale (5, very important; 4, fairly important; 3, undecided; 2, fairly unimportant; 1, not important).

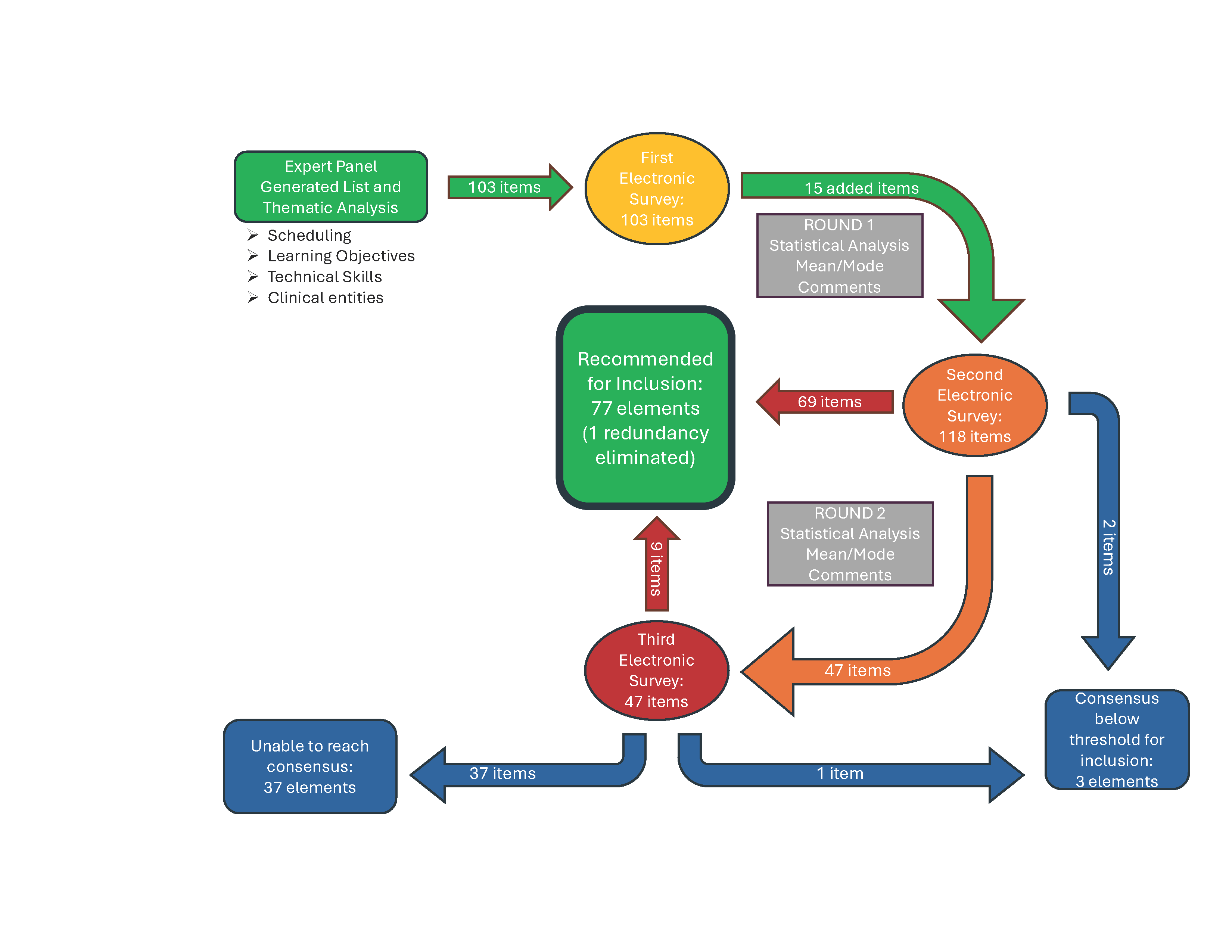

Three total rounds of ranking were completed, with no attrition among the panelists. Between rounds, we used statistical analysis to determine the mean and mode of each item, which were provided as feedback to the panelists, along with added elements for consideration and comments in round 2. Panelists were instructed to rate each item with a goal of achieving consensus. For the final round, only items that had not yet achieved consensus or recommendation for inclusion were included, along with the mean, mode, and comments. The schematic of the process appears in Figure 1.

Consensus for the purpose of this group was defined as an item receiving unanimous ranking from all participants. Recommendation for inclusion in the curriculum required an item to receive scores of 4 or 5 from all participants (fairly important or very important, respectively); a unanimous score was not required.

The panel generated 118 curricular elements for consideration: 39 reached consensus, and 78 were recommended for inclusion. One element was later deemed redundant and eliminated. The elements for consideration are listed in Table 2. A total of 28 items received a unanimous ranking of 5, indicating very important elements to include in a fourth-year MSK preceptorship. Another 42 items received mixed rankings of 4 or 5, indicating that all panelists found these items to be at least fairly important. Seven items received a unanimous ranking of 4, with all panelists agreeing these items were fairly important; and 3 items received a unanimous ranking of 3 (undecided). For another 37 elements, the panel could not agree on their importance after 3 rounds.

|

Category

|

Very important (unanimous 5)—28 items

|

Mixed very important and fairly important (mixed 4 and 5)—42 items

|

Fairly important (unanimous 4)—7 items

|

Undecided whether it should be included in the curriculum (unanimous 3)—3 items

|

|

Scheduling

|

1. Spend time in clinic with PCSM physician

|

1. Student to present an MSK-topic article for journal club

|

1. Clinic time with physical therapists

|

1. Should be modeled after a fourth-year subinternship

|

|

Learning objectives

|

1. Describe provocative tests for common conditions

2. Differential diagnosis for shoulder, knee, wrist, and ankle pain

3. Review relevant anatomy of shoulder

4. Review relevant anatomy of knee

5. Develop a general approach to treating common injuries: RICE vs POLICE

6. Develop a general approach to examine any joint: IPASS

7. Develop a general approach to any musculoskeletal complaint (ie, how to reason through HPI/PE to distinguish tendon vs joint vs nerve etiology)

8. Recognize time-sensitive and emergent injuries (ie, neurovascular compromise, compartment syndrome, fracture dislocation)

9. Take a targeted pain HPI (ie, inciting event, location, treatments tried, aggravating factors, and key questions of popping, locking, instability, weakness)

|

1. Know indications for when to splint vs cast

2. Review relevant anatomy of elbow

3. Review relevant anatomy of wrist

4. Review relevant anatomy of spine

5. Review relevant anatomy of hip

6. Review relevant anatomy of ankle

7. Review relevant anatomy of hand

8. Review relevant anatomy of foot

9. Read and discuss AMSSM/international consensus on concussion

10. Describe the indications, risks, and technique for steroid injection of knee and subacromial

11. Recognize management differences for traumatic vs septic bursitis

12. Order appropriate imaging: X-ray views, CT vs MRI, dynamic ultrasound

13. Identify when not to order imaging (choosing wisely, Ottawa foot/ankle, Canadian C-spine rules)

14. Appreciate that in skeletally immature, bony injuries are more common than soft tissue injuries

15. Describe the indications, risks, and long-term pros/cons of steroid injections

|

1. Identify where to find reliable sources for home exercise program for rehab

|

N/A

|

|

Category

|

Very important (unanimous 5)—28 items

|

Mixed very important and fairly important (mixed 4 and 5)—42 items

|

Fairly important (unanimous 4)—7 items

|

Undecided whether it should be included in the curriculum (unanimous 3)—3 items

|

|

Technical skills

|

1. Structured workshop on shoulder exam, and longitudinal practice

2. Structured workshop on knee exam, and longitudinal practice

3. Structured workshop on back exam, and longitudinal practice

4. Structured workshop on hip exam, and longitudinal practice

|

1. In-office concussion education/counseling and management

2. Structured workshop on elbow exam, and longitudinal practice

3. Structured workshop on wrist exam, and longitudinal practice

4. Structured workshop on ankle exam, and longitudinal practice

5. Structured workshop on hand/finger exam, and longitudinal practice

6. Structured workshop on foot exam, and longitudinal practice

7. Observe ultrasound of joint effusion

8. Practice knee and subacromial injections on patient

9. Practice literature search for evidence-based treatment plans

|

1. Complete preparticipation physical form

|

1. Repetitions with ultrasound scanning to practice image acquisition

|

|

Clinical entities

|

1. Carpal tunnel syndrome

2. Cervical radiculopathies

3. Lumbosacral radiculopathies

4. ACL injury

5. Meniscus injury

6. Rotator cuff injury

7. Concussion

8. Red flag in head injuries

9. Red flag in back pain

10. Patellar tendonitis

11. Achilles tendonitis

12. Lateral epicondylitis

13. Sciatica

14. Acute and subacute pain management: NSAID indications/ contraindications, safer opioid practices, nonpharm treatments

|

1. Can’t miss emergencies*

2. Pediatric conditions

3. Septic joint

4. Acute traumatic nerve palsies

5. Large joint dislocation

6. Compartment syndrome

7. Spinal injuries/eval to clear the spine in trauma

8. Growth plate injuries and Salter-Harris classification

9. Lisfranc injury

10. Meralgia paresthetica

11. Tibia fracture

12. Distal fibula fracture

13. Jones fracture

14. Scaphoid fracture

15. Smith/Colles fracture

16. Exercise prescription

17. Fracture management of peripheral bones (elbow/knee and distal)

|

1. Nursemaid elbow

2. Scoliosis

3. Developmental hip dysplasia

4. Relative energy deficiency in sport, overtraining

|

1. Altitude sickness

|

This study provides a valuable resource for family medicine educators aiming to enhance MSK medicine training in UME. Despite recent outlines of EPAs in sports medicine for UME,12 the curriculum remains broad. This study distills the subject into specific, clinically observable, and attainable mini-EPAs, serving as a framework to address MSK insufficiencies prior to medical school graduation. While extensive, this list can be personalized based on students’ strengths and weaknesses, promoting a learner-centered and growth mindset-driven educational model. The list is designed to be used in creating a fourth-year elective or in redesigning fourth-year family medicine internships, preinternship boot camps, and residency transition courses, and adds value to family medicine education by bringing educators’ attention to the unmet need in the competency-based medical education framework: integrating UME and graduate medical education (GME) curricula to foster clinical competency in MSK medicine.

The consensus curricular elements include clinical anatomy review, particularly the shoulder and knee, and emphasize a systematic and differential-informed approach to evaluation and management of MSK issues seen by family physicians. Key recommendations include longitudinal practice of physical exam skills at the bedside, reinforcement of relevant anatomy, specific frameworks for MSK medical care, and a consensus-driven selection of high-yield clinical entities from which to choose.

For validity and expertise,23 we included members of the group that revised the American Academy of Family Physicians reprint on MSK education topics 24 to derive the most useful elements for graduating medical students. To balance potential bias, curriculum design experts without specialized sports medicine training were included. The specific mention of the shoulder, knee, back, and hip examinations by the expert panel is worth noting. Interestingly, the hip exam was ranked very important, despite no proposals for differential diagnoses of hip pain, indicating a possible bias in the panel’s expertise.

The panelists strongly recommended time in a primary care MSK clinic for repeated, supervised physical exam practice. This repetition of numerous joint examinations, in conjunction with anatomy review and structured workshops, should help learners review, reinforce, and expand their knowledge as intended within a spiral curriculum. This approach, based on constructivist educational theory that active learning connects new knowledge to preexisting knowledge, 25 has shown improved physical exam skills in preclinical medical education;26 and the clinical context of this experience should associate a catalog of diagnostic entities with those physical exam findings.

While the modified Delphi technique classically involves real-time discussion, this project was conducted asynchronously via telephone and email. Nevertheless, the panel agreed on the inclusion of a substantial number of curricular components. Future studies should explore how to implement these recommendations, particularly without an integrated sports medicine fellowship, and assess the outcomes of a curriculum targeting these elements.

This study adds novel perspectives to family medicine education by preparing soon-to-be GME trainees to confidently practice MSK medicine, reducing reliance on specialists and improving health care utilization. Implementing MSK-focused educational experiences with real patients and real pathology, rather than standardized patients, could close the gap between MSK knowledge and required competence for GME settings.

Acknowledgments

Authors Jordan Knox, Stephen Carek, Rajalakshmi Cheerla, Alexei DeCastro, Jason W. Deck, Sherilyn DeStefano, Michael Petrizzi, Dan Sepdham, Irvin Sulapas, James Wilcox, Matthew W. Wise, and Velyn Wu are members of the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Musculoskeletal and Sports Medicine Educational Collaborative.

Author Jennifer Hartmark-Hill is a member of the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Medical Student Education Collaborative.

Author Susan Cochella is a member of the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Family Medicine Clerkship Core Curriculum Task Force.

References

-

-

Skelley NW, Tanaka MJ, Skelley LM, LaPorte DM. Medical student musculoskeletal education: an institutional survey.

J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(19):e146.

doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.01286

-

Al Maini M, Al Weshahi Y, Foster HE, et al. A global perspective on the challenges and opportunities in learning about rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in undergraduate medical education: white paper by the World Forum on Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases (WFRMD).

Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(3):627-642.

doi:10.1007/s10067-019-04544-y

-

Wang T, Xiong G, Lu L, Bernstein J, Ladd A. Musculoskeletal education in medical schools: a survey in California and review of literature.

Med Sci Educ. 2021;31(1):131-136.

doi:10.1007/s40670-020-01144-3

-

McDaniel CM, Forlenza EM, Kessler MW. Effect of shortened preclinical curriculum on medical student musculoskeletal knowledge and confidence: an institutional survey.

J Surg Educ. 2020;77(6):1,414-1,421.

doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.04.011

-

Wu V, Goto K, Carek S, et al. Family Medicine Musculoskeletal Medicine Education: A CERA Study.

Fam Med. 2022;54(5):369-375.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2022.975755

-

-

Khorsand D, Khwaja A, Schmale GA. Early musculoskeletal classroom education confers little advantage to medical student knowledge and competency in the absence of clinical experiences: a retrospective comparison study.

BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:46.

doi:10.1186/s12909-018-1157-7

-

Denq W, Fox JD, Lane A, et al. Impact of sports medicine and orthopedic surgery rotations on musculoskeletal knowledge in residency.

Cureus. 2021;13(3):e14211.

doi:10.7759/cureus.14211

-

-

Danilovich N, Kitto S, Price DW, Campbell C, Hodgson A, Hendry P. Implementing competency-based medical education in family medicine: a narrative review of current trends in assessment.

Fam Med. 2021;53(1):9-22.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.453158

-

Ferderber M, Wilson K, Buchanan BK, et al. Sports medicine curricular recommendations for undergraduate medical education.

Curr Sports Med Rep. 2023;22(5):172-180.

doi:10.1249/JSR.0000000000001064

-

Sabesan VJ, Schrotenboer A, Habeck J, et al. Musculoskeletal education in medical schools: a survey of allopathic and osteopathic medical students.

J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2018;2(6):e019.

doi:10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-18-00019

-

Orner CA, Soin SP, Mahmood B, Gorczyca JT, Nicandri GT, DiGiovanni BF. Increasing the educational value of the orthopaedic subinternship: the design and implementation of a fourth-year medical student curriculum.

J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2021;5(1):e20.00240.

doi:10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-20-00240

-

Amidon J, Taylor SS, Hinton S. Practice impact of a dedicated LGBTQ+ clinical exposure during residency.

PRiMER. 2023;7:24.

doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2023.329607

-

Walters E, Sairenji T. STFM task force releases a standardized family medicine sub-internship curriculum.

Ann Fam Med. 2022;20(3):289-290.

doi:10.1370/afm.2839

-

Clayton R, Perera R, Burge S. Defining the dermatological content of the undergraduate medical curriculum: a modified Delphi study.

Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(1):137-144.

doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07190.x

-

Wattanapisit A, Petchuay P, Wattanapisit S, Tuangratananon T. Developing a training programme in physical activity counselling for undergraduate medical curricula: a nationwide Delphi study.

BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e030425.

doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030425

-

Asif I, Thornton JS, Carek S, et al. Exercise medicine and physical activity promotion: core curricula for US medical schools, residencies and sports medicine fellowships: developed by the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine and endorsed by the Canadian Academy of Sport and Exercise Medicine.

Br J Sports Med. 2022;56(7):369-375.

doi:10.1136/bjsports-2021-104819

-

-

Jnanathapaswi SG. Thematic analysis & coding: an overview of the qualitative paradigm. In:

An Introduction to Social Science Research. APH Publishing; 2021:98-105.

doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.17159249.

-

McKim, C. Meaningful member-checking: a structured approach to member-checking. Am J Qualitative Res. 2023;7(2):41-52.

-

ChatGPT. Why ChatGPT should not be used to write academic scientific manuscripts for publication.

Ann Fam Med. 2023;2958.

doi:10.1370/afm.2982

-

-

Dennick R. Constructivism: reflections on twenty five years teaching the constructivist approach in medical education.

Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:200-205.

doi:10.5116/ijme.5763.de11

-

Yu JC, Guo Q, Hodgson CS. Deconstructing the joint examination: a novel approach to teaching introductory musculoskeletal physical examination skills for medical students.

MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10945.

doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10945

There are no comments for this article.