Background and Objectives: Institutional racism causes worse health outcomes for patients of racial/ethnic minority groups via limited access to health care, disparities in quality of care delivered, and lack of physician diversity. Increased attention to racism in 2020 led many medical institutions to examine their diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts. In the context of increased national attention to health equity, this study sought to investigate the current status of DEI infrastructure by evaluating leadership and support related to DEI in family medicine departments in 2020 and 2021.

Methods: We analyzed department and chair characteristics as well as departmental DEI infrastructure (ie, leadership and actions) from Association of Departments of Family Medicine survey data in 2020 (data collected from June to September 2020) and 2021 (data collected from September to December 2021). We performed multiple regression analyses to evaluate whether department characteristics or specific DEI activities were associated with increased DEI infrastructure in 2021 compared to 2020.

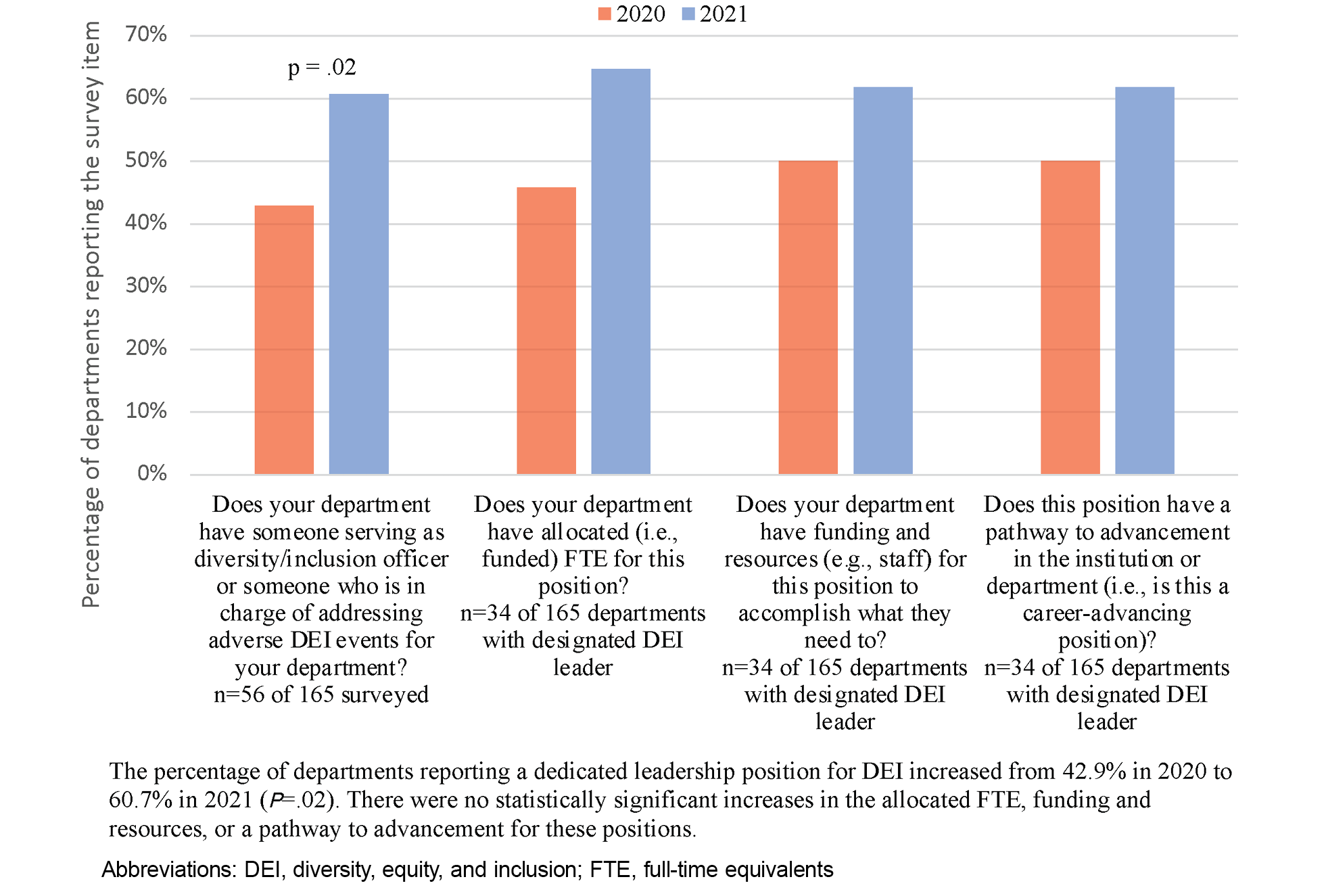

Results: Of the 165 department chairs sent the survey in both 2020 and 2021, 56 (33.9%) responded both years. Departments with a designated DEI leader increased from 42.9% in 2020 to 60.7% in 2021, but about 40% of departments lacked key supports for this position (ie, funding, staff support, and a pathway for advancement). Regression analysis did not demonstrate associations between independent variables and three measures of departmental DEI activities.

Conclusions: This study demonstrates that designated leadership for DEI work increased in family medicine departments between 2020 and 2021.

Racism leads to poor health outcomes for patients of racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States. 1 Jones described institutional racism as the “differential access to the goods, services, and opportunities of society by race,” which can result in worse health outcomes and decreased diversity within institutions. 2 Within medicine, institutional racism manifests in several ways. 3 First, institutional racism occurs through exclusion from the profession and professional development. A historical example of this is reflected in the inequitable reforms made to historically Black medical schools following the 1910 Flexner Report. 4 Today, structural barriers for Black physicians include discrimination during medical admissions processes and lack of mentorship. 5 Second, institutional racism appears in the learning environment (eg, using racial stereotypes in exam questions and clinical vignettes). 6, 7 Finally, institutional racism exists in problematic race-based algorithms and guidelines such as the use of “Black” or “non-Black” race in glomerular filtration rate equations, leading to limited access to renal transplantation for Black patients. 8, 9

Institutional racism limits diversity and inclusion in the health care workforce. In 2022, only 5.2% of US physicians were Black and 6.3% were Latinx despite these groups making up 13.6% and 19.1% of the US population, respectively. 10, 11 Physicians of minority racial/ethnic groups are more likely to report workplace discrimination than White health care workers (eg, 59%–71% of Black physicians compared to 6%–29% of White physicians). 12 Such discrimination is associated with emotional distress and job dissatisfaction. 13, 14 Underrepresentation also contributes to health disparities, given that provider-patient race concordance is associated with improved patient outcomes such as increased engagement in primary care and greater acceptance of preventative health services. 15, 16

In 2020, the “dual pandemic” of COVID-19 and the increased national consciousness of racism following the highly publicized killing of several Black Americans, namely Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, prompted many medical institutions to examine and address practices that cause racial disparities. 3, 17, 18 Family medicine, a field that cares for whole families and communities with a historically counterculture orientation to social reform, took special interest in promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) principles. 19

Beginning with its 2020 annual survey, the Association of Departments of Family Medicine (ADFM) sought to quantify DEI activities. Jacobs et al described the 2020 survey findings and outlined steps for departments to promote DEI: (1) perform a departmental self-assessment, (2) develop a strategic plan, (3) build DEI infrastructure and support its maintenance, and (4) measure and disseminate outcomes. 20 Additional recommended DEI infrastructure has included a designated diversity officer supported by sufficient compensation and resources, DEI training for all departmental members, and systems to recruit, select, and support individuals from diverse backgrounds. 21, 22 In 2021, the ADFM survey expanded the DEI infrastructure questions.

This study aimed to describe and compare DEI activities of family medicine departments in 2020 and 2021. The study hypothesis was that departmental DEI infrastructure would increase in 2021 compared to 2020 and that the presence of a DEI leader in 2020 would be associated with increases in this work.

Survey

Before changes in survey structure and timing in 2022, the ADFM surveyed the chairs of its more than 150 member departments of family medicine annually. ADFM membership is obtained through an application process and includes virtually all allopathic departments, many regional branch campuses, several osteopathic departments, and several departments in large regional medical centers. While most members and departments are in the United States, a small number are also Canadian (three of the 166 members in 2021 were in Canada). Membership information is maintained by the ADFM in an internal annual report and was provided to the authors by email from an ADFM staff member on April 8, 2024. In addition to medical schools, some departments have affiliated residency training sites. The ADFM’s DEI Committee developed and added questions about departmental DEI activities to the 2020 survey, open from June 29 to September 2, 2020. The 2021 survey, open from September 8 to December 15, 2021, included similar questions as well as new questions regarding notable changes to departmental DEI activities. In 2020, 165 departments were invited to respond to the survey, and 166 departments were invited to respond to the 2021 survey. Survey links were distributed via email to an Internet-based system (Google forms) with reminders every 2 weeks. The authors requested the survey data, and ADFM staff provided the deidentified data via email on February 17, 2023.

Descriptive Analyses

Restricting our sample to departments that responded to both the 2020 and 2021 survey, we analyzed frequency characteristics for department chairs surveyed in 2021 (permanent vs interim, duration of position, and self-reported likelihood of continuing in their role), department characteristics surveyed in 2021 (public vs private and number of matriculants in medical school per year), and responses to the DEI-specific questions in both 2020 and 2021. These binary (yes/no) questions included whether the department had a dedicated diversity/inclusion officer or individual responsible for addressing adverse DEI events, and if so, whether the department allocated (ie, funded) full-time equivalents (FTE) for that position, whether the department allocated resources (eg, staff) for the position, and whether the position had a pathway to advancement. Additionally, we analyzed responses about whether departments had eight specific DEI actions in place in 2020 and 2021. We used the two-sided McNemar test to determine differences in frequencies of these items between 2020 and 2021. We used the paired two-sided t test to compare the mean composite scores for dedicated DEI position and DEI actions. Of note, while we included eight DEI actions in the descriptive analysis, we included only seven in the comparison testing and regression models because one item (results of a climate survey) was asked differently in the 2020 and 2021 surveys and therefore could not be compared between years.

Regression Analyses

We performed multiple regression analyses with standard predictor entry to identify associations between changes in DEI efforts between 2020 and 2021 and predictor variables. Predictor variables included institution and department chair characteristics (summarized in Table 1) and reported departmental DEI efforts. A composite variable was created to capture the support of a dedicated DEI position. This variable included whether a position existed (1 point), whether that position had FTE (1 point), whether the position had resources (1 point), and whether the position had career advancement opportunities (1 point). Departments that did not have a position scored a 0, and departments with positions that had FTE, resources, and advancement opportunities scored a maximum of 4 points. We calculated a computed variable on the difference in the score between 2020 and 2021. A composite variable was created to capture reported DEI actions. This variable included whether departments reported the following components: a DEI mission statement, a DEI values statement, a DEI hiring plan for residents, a DEI hiring plan for faculty, a DEI hiring plan for staff, a formal written diversity plan, and a DEI curriculum for medical students taught by the department. The composite variable for each year ranged from 0 to 7.

|

Characteristic

|

Department survey respondents (N=56 of 165 surveyed), n (%)

|

|

Department setting

|

|

Allopathic medical school (MD)

|

54 (96.4)

|

|

Regional medical center (eg, stand-alone program)

|

1 (1.8)

|

|

Regional campus for allopathic medical school, affiliation with osteopathic medical school, community hospital

|

1 (1.8)

|

|

Institution type

|

|

Public

|

38 (67.9)

|

|

Private

|

18 (32.1)

|

|

Size of medical school class (number of matriculants per year)

|

|

Small (<75)

|

7 (12.5)

|

|

Medium (75–149)

|

19 (33.9)

|

|

Large (≥150)

|

30 (53.6)

|

|

Chair status

|

|

Permanent

|

51 (91.1)

|

|

Interim

|

5 (8.9)

|

|

Chair years in position

|

|

<1 year

|

8 (14.3)

|

|

1–3 years

|

14 (25.0)

|

|

4–7 years

|

21 (37.5)

|

|

8 or more years

|

13 (23.2)

|

|

Anticipated continuation in chair position for next 3 years

|

|

Unlikely

|

8 (14.3)

|

|

Possibly

|

9 (16.1)

|

|

Probably

|

7 (12.5)

|

|

Likely

|

32 (57.1)

|

Three outcome variables explored changes in DEI efforts between 2020 and 2021:

-

change in the composite DEI actions variable between 2020 and 2021;

-

change in Likert scale between 2020 and 2021 (On a scale of 1 to 5, how well do you feel your department does in promoting diversity, inclusion, health equity, and antioppression?); and

-

a dichotomous report in 2021 about whether notable improvements in DEI occurred between 2020 and 2021 (yes/no).

We used linear regression to predict the change in the composite DEI actions variable from 2020 to 2021. Predictors for this model included the change in dedicated DEI position support from 2020 to 2021, type of institution, size of institution, chair status, chair duration, chair likelihood to continue, and whether a dedicated DEI position existed in 2020. We used linear regression to predict the change in Likert score change. Predictors for this model included all the predictors included in the previous linear regression as well as the number of DEI actions in 2020 (0–7). We used logistic regression to predict whether notable improvements occurred. Predictors for this model were the same as the second linear regression. We performed a sensitivity analysis where we excluded from the analysis departments that had all DEI actions in place in 2020 because they could not increase from 2020 to 2021.

We used SPSS Statistics for Windows version 29 (IBM Corp) for all analyses. The University of Washington Human Subjects Division deemed this research exempt from formal institutional review.

Descriptive Statistics

Of the 165 departments sent the survey in both 2020 and 2021, 94 chairs (57.0%) responded in 2020, 66 chairs (40.0%) responded in 2021, and 56 chairs (33.9%) responded both years. Table 1 shows characteristics of the 56 departments that responded both years and of their chairs in 2021, which was the only year when chair and program demographic questions were included.

The frequencies of responses to questions related to the presence of a DEI leader and departmental supports for that role are displayed in Figure 1. The number of departments with a designated DEI leader increased from 24 (42.9%) in 2020 to 34 (60.7%) in 2021 (P=.02). The 34 programs with DEI positions reflected 20 departments that maintained a position and 14 that gained a position, while 4 departments with a DEI position in 2020 did not report one in 2021. The mean composite score reflecting the presence of and supports for a dedicated DEI position increased from 1.05 (range=0–4, SD=1.51) in 2020 to 1.75 (range=0–4, SD=1.69) in 2021 (P<.01). Although more than half of departments had a designated DEI leader in 2021, about 40% of such positions had no allocated funding, resources, or pathways for advancement. We found no statistically significant changes in the three individual measures of support for the DEI leadership position from 2020 to 2021.

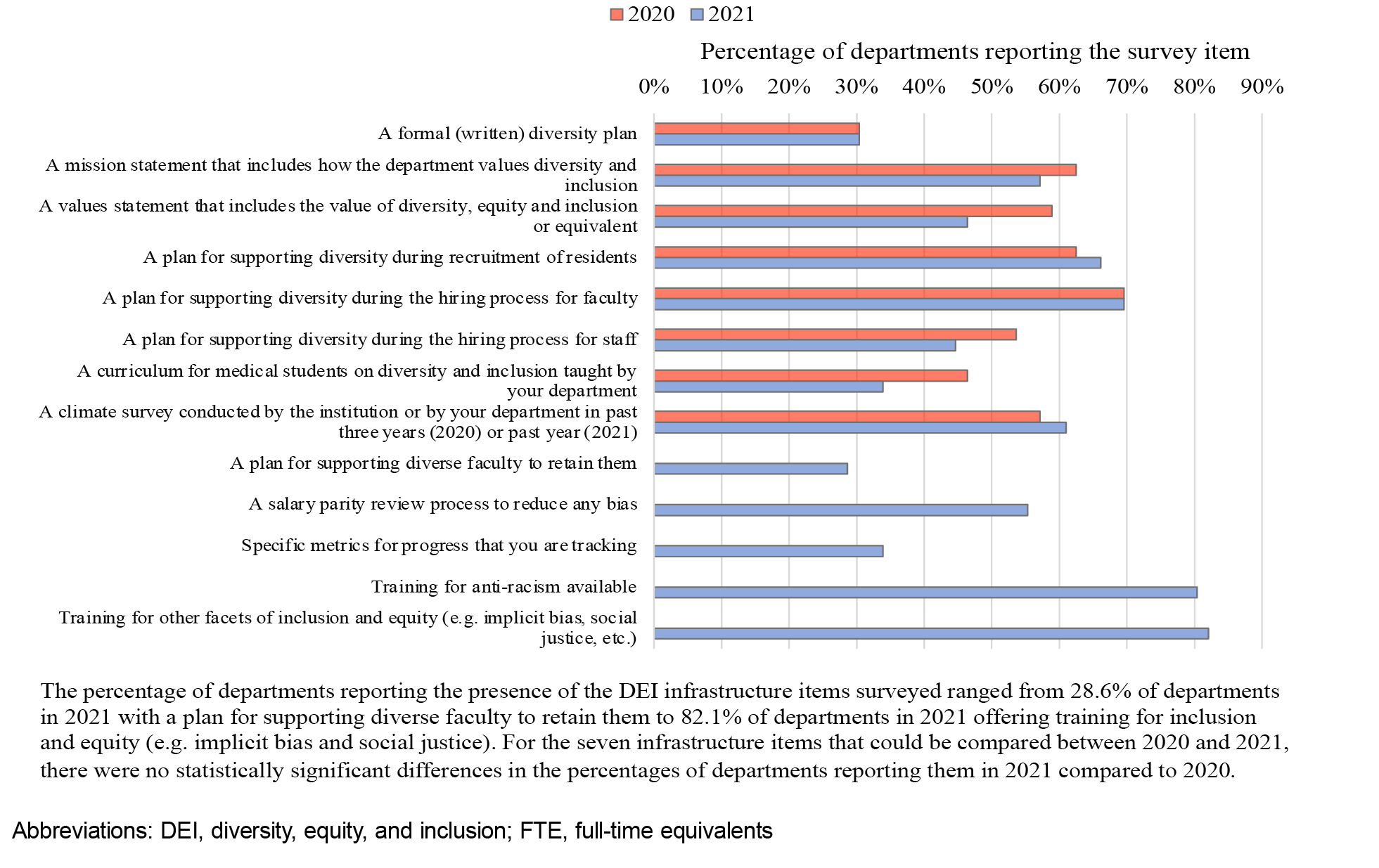

Figure 2 displays departmental DEI actions in 2020 and 2021. For the seven DEI action items that could be compared between 2020 and 2021, we found no statistically significant change in the mean DEI actions composite score between 2020 when the mean DEI actions composite score was 3.84 (range=0–7, SD=1.72) and 2021 when the mean DEI actions composite score was 3.48 (range=0–7, SD=2.08, P=.23). We found no statistically significant changes in the proportions of departments with each of the seven DEI actions included in the survey in both 2020 and 2021 for which we could measure differences between years. Of the eight departmental DEI actions included in the survey in both 2020 and 2021, the percentage of departments reporting them were highest for those with plans for supporting diversity during recruitment of faculty (69.6% in 2020 and 2021, P>.99) and residents (62.5% in 2020 and 66.1% in 2021, P=.59), a mission statement for how the department values diversity and inclusion (62.5% in 2020 and 57.1% in 2021, P=.47), and having results from a climate survey (57.1% with such a survey in the past 3 years in 2020 and 61% in the past year in 2021 (P value not calculated due to the questions being asked differently in 2020 and 2021). The DEI actions with the lowest percentage of departments reporting them were a formal diversity plan (30.4% in 2020 and 2021, P>.99), a curriculum for medical students on diversity and inclusion taught by the department (46.4% in 2020 and 33.9% in 2021, P=.14), a plan for supporting diversity during recruitment of staff (53.6% in 2020 and 44.6% in 2021, P=.25), and a values statement for how the department values DEI (58.9% in 2020 and 46.4% in 2021, P=.16). Five new items were included in the 2021 survey that were not included in the 2020 survey. Of these, 80.4% of departments reported training for antiracism, 82.1% of departments reported training for other facets of inclusion and equity (eg, implicit bias, social justice), 55.3% of departments reported a salary parity review process to reduce bias, 28.6% of departments reported a plan for supporting diverse faculty to retain them, and 33.9% of departments reported tracking the progress of specific metrics.

Regression Analyses

The multiple regression analyses are summarized in Table 2. The linear regression predicting the number of DEI actions in 2021 compared to 2020 demonstrated no associations with the characteristics of departments or chairs collected in the survey, the presence of a designated DEI position in 2020, or the DEI position composite score. Similarly, the linear regression model found no statistically significant associations between predictors and department chairs’ responses to the question of how well they feel their department does in promoting DEI. Finally, the logistic regression model found no associations between predictors and department chairs’ responses to the question, “Since the last year’s survey (August 2020), have there been notable actions or programs to improve or/and address DEI at your departmental level?” The sensitivity analysis that excluded from the analysis departments that had all infrastructure items in place in 2020 did not demonstrate any difference in the results.

|

Multiple linear regression with

standard predictor entry

for change in DEI actions component change

(N=56)

|

|

|

F

(7)

|

P

|

R2

|

β

|

t

|

P

|

|

DEI actions component change

|

1.23

|

.31

|

0.03

|

|

|

|

|

Intercept

|

|

|

|

|

0.29

|

.78

|

|

DEI position support change

|

|

|

|

0.03

|

0.21

|

.83

|

|

Institution type (public/private)

|

|

|

|

-0.17

|

-1.28

|

.21

|

|

Institution size

|

|

|

|

0.08

|

0.60

|

.55

|

|

Chair status

|

|

|

|

0.34

|

2.01

|

.05

|

|

Chair duration

|

|

|

|

-0.25

|

-1.49

|

.14

|

|

Chair anticipation of continuation in position

|

|

|

|

-0.07

|

-0.44

|

.66

|

|

DEI position 2020

|

|

|

|

-0.13

|

-0.82

|

.41

|

|

Multiple linear regression with standard predictor entry

for Likert scale change

(N=56)

|

|

|

F

(8)

|

P

|

R2

|

β

|

t

|

P

|

|

Likert scale change

|

1.21

|

.31

|

0.03

|

|

|

|

|

Intercept

|

|

|

|

|

-0.36

|

.72

|

|

DEI position support change

|

|

|

|

0.21

|

1.34

|

.19

|

|

Institution type (public/private)

|

|

|

|

-0.10

|

-0.75

|

.46

|

|

Institution size

|

|

|

|

0.12

|

0.82

|

.42

|

|

Chair status

|

|

|

|

-0.01

|

-0.05

|

.96

|

|

Chair duration

|

|

|

|

-0.02

|

-0.14

|

.89

|

|

Chair anticipation of continuation in position

|

|

|

|

-0.05

|

-0.33

|

.75

|

|

DEI actions 2020

|

|

|

|

0.17

|

1.19

|

.24

|

|

DEI position 2020

|

|

|

|

-0.21

|

-1.31

|

.20

|

|

Multiple logistic regression with standard predictor entry

for notable improvements change (N=56)

|

|

|

χ2(8)

|

P

|

R2

|

β

|

SE

|

P

|

|

Proportion of “yes” responses to notable improvements question

|

19.19

|

.01

|

0.50

|

|

|

|

|

DEI position support change

|

|

|

|

1.74

|

1.16

|

.13

|

|

Institution type (public/private)

|

|

|

|

-0.51

|

0.54

|

.35

|

|

Institution size

|

|

|

|

0.33

|

0.67

|

.62

|

|

Chair status

|

|

|

|

-10.10

|

7719.06

|

.99

|

|

Chair duration

|

|

|

|

-0.53

|

0.64

|

.41

|

|

Chair anticipation of continuation in position

|

|

|

|

0.20

|

0.41

|

.63

|

|

DEI actions 2020

|

|

|

|

0.42

|

0.28

|

.14

|

|

DEI position 2020

|

|

|

|

2.79

|

1.63

|

.09

|

Our study analyzed changes to departmental DEI activities in family medicine departments in 2021 compared to 2020. Our hypothesis was that the increased national attention on race and racism would prompt increased DEI infrastructure in family medicine departments in 2021. Survey results demonstrated an increase in designated DEI leaders in departments of family medicine but no corresponding increase in DEI activities. Only about 60% of DEI leadership positions had financial, logistical, or professional supports in 2021.

In reviewing the state of DEI activities in family medicine departments in 2020, Jacobs et al recommended that departments begin with a self-assessment and build a strategic plan from that initial assessment. 20 Our findings show that many departments had not yet taken these foundational steps in 2021. Once a formalized plan for DEI is created, programs then can work to build and maintain infrastructure to support DEI. 20 These steps may include, but are not limited to, the items surveyed in this study.

Limitations to this study included, first, the survey response rate of 34% may have introduced nonresponse bias and led to underpowered statistical testing and subsequent large standard deviations. Second, the survey was distributed in the summer of 2021 and may have been too soon to detect changes prompted by the antiracism movement of 2020, because departmental and institutional change can take months or years to implement, especially during a pandemic requiring significant attention. Third, while assessing for change over a longer time period would be ideal, changes to the survey format and questions in 2021 prevent continued analysis. Future studies should track these changes longitudinally. Fourth, the responses by department chairs, who may not be familiar with all departmental actions and policies related to DEI work, may have decreased the reliability of survey responses. Additionally, some activities may be housed under a medical school rather than the department itself, and therefore chair responses would not reflect work done by the medical school or broader institution toward their DEI goals. Fifth, many variables were captured in binary responses, which may limit identification of DEI efforts that cannot be answered in a yes/no question format. Sixth, the dataset did not include demographics of department chairs, which precluded investigation of associations between their identities and departmental policies. Finally, this study was limited by the survey, which measured only a subset of the wide-ranging policies and actions that are required to promote health equity as well as true diversity and belonging for staff, faculty, and learners in family medicine departments. Future surveys should include a more comprehensive list of departmental actions and policies that constitute DEI infrastructure as well as metrics of diversity and inclusion among departmental members.

The DEI Committee of the ADFM recently published a framework to measure DEI outcomes in family medicine departments; this framework can be used or adapted as departments create plans to promote DEI in their settings. 23 We recognize the considerable backlash to DEI work since 2021, including state laws restricting teaching this content area and Supreme Court restrictions on Affirmative Action. Despite this change in the national environment, we implore family medicine departments to seek creative solutions to commencing or continuing this work regardless of a designated DEI leader, because the lack of DEI leadership should not be a barrier to initiating the steps to promote DEI efforts. Ross et al recommended that academic medical departments implement a process to measure and report the racial and ethnic identities of all members of the departmental community, including faculty, staff, and learners, in order to inform progress toward diversity. 3 In addition, Vela et al urged departments to create methods for systematically reporting and addressing incidents of bias. 24 Departments also should implement and measure policies aimed at promoting diversity and inclusion in hiring and retention for all department members. These policies should include structural changes to search committees and interviewers to mitigate bias and improve diversity as well as dedicated orientation to resources, mentorship, adequate compensation for DEI work, and funding opportunities for department members from minority racial/ethnic groups. 3, 18, 25 These structural changes can help offset the extra responsibilities that faculty and students from racial/ethnic groups that are underrepresented in medicine take on to promote diversity. 26 In the educational domain, departments should ensure that their curricula teach both learners and teachers to promote health equity and are free of biased content and that all department faculty receive high-quality antiracism training. 3, 18, 25

This study demonstrates that while DEI leadership increased, a significant need still exists for family medicine departments to build and maintain DEI infrastructure. We believe that health care providers and systems cannot accept the ongoing unequal treatment of patients and colleagues based on race. We urge leaders in every department to take concrete steps to promote DEI by performing a departmental assessment, creating formalized plans, and then implementing and evaluating comprehensive departmental DEI infrastructure.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Amanda Weidner and Sam Elwood of ADFM who provided the survey data and information about the survey methods.

References

-

-

Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale.

Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1,212-1,215.

doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.8.1212

-

Ross PT, Lypson ML, Byington CL, Sánchez JP, Wong BM, Kumagai AK. Learning from the past and working in the present to create an antiracist future for academic medicine.

Acad Med. 2020;95(12):1,781-1,786.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003756

-

Steinecke A, Terrell C. Progress for whose future? the impact of the Flexner Report on medical education for racial and ethnic minority physicians in the United States.

Acad Med. 2010;85(2):236-245.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c885be

-

Wingfield AH, Chavez K. Getting in, getting hired, getting sideways looks: organizational hierarchy and perceptions of racial discrimination.

Am Sociol Rev. 2020;85(1):31-57.

doi:10.1177/0003122419894335

-

Krishnan A, Rabinowitz M, Ziminsky A, Scott SM, Chretien KC. Addressing race, culture, and structural inequality in medical education: a guide for revising teaching cases.

Acad Med. 2019;94(4):550-555.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002589

-

Acquaviva KD, Mintz M. Perspective: are we teaching racial profiling? The dangers of subjective determinations of race and ethnicity in case presentations.

Acad Med. 2010;85(4):702-705.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d296c7

-

Vyas DA, Eisenstein LG, Jones DS. Hidden in plain sight—reconsidering the use of race correction in clinical algorithms.

N Engl J Med. 2020;383(9):874-882.

doi:10.1056/NEJMms2004740

-

Delgado C, Baweja M, Burrows NR, et al. Reassessing the inclusion of race in diagnosing kidney diseases: an interim report from the NKF-ASN Task Force.

Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;78(1):103-115.

doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.03.008

-

-

-

Filut A, Alvarez M, Carnes M. Discrimination toward physicians of color: a systematic review.

J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112(2):117-140.

doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2020.02.008

-

Thomas-Hawkins C, Flynn L, Zha P, Ando S. The effects of race and workplace racism on nurses’ intent to leave the job: the mediating roles of job dissatisfaction and emotional distress.

Nurs Outlook. 2022;70(4):590-600.

doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2022.03.001

-

Peterson NB, Friedman RH, Ash AS, Franco S, Carr PL. Faculty self-reported experience with racial and ethnic discrimination in academic medicine.

J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(3):259-265.

doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.20409.x

-

Ma A, Sanchez A, Ma M. The impact of patient-provider race/ethnicity concordance on provider visits: updated evidence from the Medical Expenditure Panel survey.

J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6(5):1,011-1,020.

doi:10.1007/s40615-019-00602-y

-

Alsan M, Garrick O, Graziani G. Does diversity matter for health? experimental evidence from Oakland.

Am Econ Rev. 2019;109(12):4,071-4,111.

doi:10.1257/aer.20181446

-

Higginbotham EJ, Hertz K, Fahl C, Duckett DB, Mahoney K, Jameson JL. Addressing structural racism using a whole-scale planning process in a single academic center.

Health Equity. 2023;7(1):487-496.

doi:10.1089/heq.2023.0093

-

Jindal M, Heard-Garris N, Empey A, Perrin EC, Zuckerman KE, Johnson TJ. Getting “our house” in order: re-building academic pediatrics by dismantling the anti-Black racist foundation.

Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(8):1,044-1,050.

doi:10.1016/j.acap.2020.08.019

-

Sturges D, Patterson DG, Bennett IM, Cawse-Lucas J. Can family medicine’s counterculture history help shape an anti-racist future?

J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(1):169-172.

doi:10.3122/jabfm.2022.01.210295

-

Jacobs CK, Douglas M, Ravenna P, et al. Diversity, inclusion, and health equity in academic family medicine.

Fam Med. 2022;54(4):259-263.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2022.419971

-

-

Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity and Inclusion in Academic Medicine: A Strategic Planning Guide. AAMC; 2016.

-

Nair S, Rodríguez JE, Elwood S, et al. Departmental metrics to guide equity, diversity, and inclusion for academic family medicine departments.

Fam Med. 2024;56(6):362-366.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2024.865619

-

Vela MB, Chin MH, Peek ME. Keeping our promise—supporting trainees from groups that are underrepresented in medicine.

N Engl J Med. 2021;385(6):487-489.

doi:10.1056/NEJMp2105270

-

Doll KM, Thomas CR Jr. Structural solutions for the rarest of the rare—underrepresented-minority faculty in medical subspecialties.

N Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):283-285.

doi:10.1056/NEJMms2003544

-

Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax?

BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):6.

doi:10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9

There are no comments for this article.