Sub-Saharan Africa is the last region of the world to fully embrace the need for education and training in family medicine. 1 In this article we reflect on the state of family medicine education and training; in particular, we focus on these key issues: advocacy, evidence of impact, barriers and enablers, and implementation strategies.

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

Family Medicine Education and Training in Sub-Saharan Africa

Robert Mash, PhD | Innocent Besigye, PhD, MMed | Akye Essuman, FWACP | Jean-Pierre Fina Lubaki, PhD | Mpundu Makasa, PhD | Martha Makwero, PhD, MMed | Gulnaz Mohamoud, PhD

Fam Med. 2025;57(5):342-348.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2025.291430

In this article we reflect on the state of family medicine education and training in sub-Saharan Africa; in particular, we focus on these key issues: advocacy, evidence of impact, barriers and enablers, and implementation strategies. Sub-Saharan Africa is the last region of the world to embrace family medicine, and adoption varies widely among countries. Family physicians with postgraduate training are relatively few. In the public sector, primary care is mostly offered by nurses or physician assistants, while in the private sector, it is offered by general practitioners. Family physicians work in both primary care and primary hospitals, in multidisciplinary teams; as clinicians, consultants, capacity builders, clinical trainers, leaders of clinical governance and may also have some managerial functions.

Advocacy for the contribution of family physicians and training programs is needed with departments of health, regulatory bodies, higher education institutions, and other health professions. Evidence of impact in the African context is limited due to the small numbers and limited research outputs.

Barriers and enablers to education and training are related to the stage of development. Key issues include a lack of academic and teaching expertise, a need to develop learning environments and clinical trainers, sufficient training posts, and appropriate deployment of new graduates.

Implementation strategies to overcome these barriers can be categorized into planning, educational, financial, quality management, and policy related strategies. A South-South-North approach to support and partnerships is advocated. More attention should be given to engaging the public on the contribution of family medicine.

The Reach of Family Medicine Education and Training

Over the last 30 years many countries have taken steps to introduce family medicine education and training, with enormous diversity in terms of the scale and maturity of training programs. Undergraduate medical training begins after high school and typically lasts for 6 years, but exposure to family medicine varies from none to more than 30 weeks. 2, 3 Postgraduate training usually takes 3 or 4 years for specialist training in family medicine. This can be via a master of medicine degree from a university or via a fellowship from a professional association such as the West African College of Physicians. In terms of such training, countries vary. For example:

-

Nigeria, Ghana, and South Africa have well-established programs;

-

Zimbabwe and the Democratic Republic of Congo have small and fragile programs; and

-

Cameroon and Rwanda have no training at all.

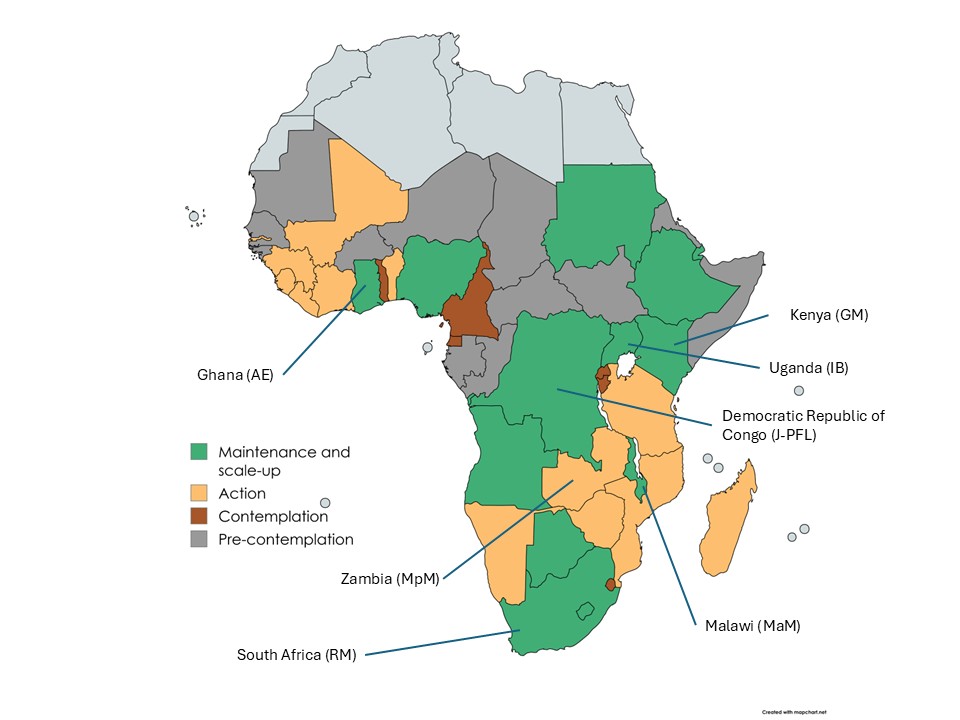

Some countries, such as Namibia, Mali, Benin, Guinea, and Madagascar have developed postgraduate diplomas in family medicine or general practice, although these do not allow registration as a specialist and are not the same as a residency. 4 Figure 1 illustrates the reach of postgraduate family medicine training in countries across the region. 5, 6

Family Doctors in African Health Systems

Although the principles of family medicine may be the same across the world, how these are put into practice differs considerably. 7 The African context is broadly characterized by a scarcity of human resources for health, and resource constraints. 8, 3 Outside of the private sector, a primary care service based on doctors is neither affordable nor feasible. Primary care is offered by a team, and first contact care is usually offered by a nurse practitioner. Other key role players in the team include community health workers and physician assistants, often known as clinical officers (Table 1). When doctors are included in the team, they do not usually have any postgraduate training and may be quite junior. Doctors with postgraduate training in family medicine are usually known as specialist family physicians. 9 Doctors without such training may be referred to as medical officers or general practitioners. Even in countries such as South Africa, however, family physicians are scarce at 0.16/10,000 population. 10

|

Type of health care worker |

Length of training |

Scope of practice |

|

Family physician |

4 years of postgraduate training |

Clinician, consultant, capacity builder, clinical trainer, clinical governance in primary care or primary hospital |

|

Medical officer or general practitioner |

6 years of undergraduate training |

Clinician in primary care or primary hospital |

|

Physician assistant (clinical officer, community health officer, clinical associate) |

2–3 years of preservice training |

First contact primary care for acute and chronic patients and/or assisting doctors in the primary hospital |

|

Nurse practitioner |

1 year of training after qualifying as a nurse |

First contact primary care for acute and chronic patients |

|

Community health worker |

Weeks–months |

Community member offering basic services in households or other community locations and linking people to health or social care |

Most countries divide the population geographically into health districts for the delivery of government health services. Each health district has one or more primary hospitals. This is the next level of expertise after primary care, and the hospitals usually work in a close functional relationship. Such hospitals are typically generalist environments with male, female, child, and maternity wards. These hospitals are critical to improving health outcomes and supporting primary care, but often have substantial skills gaps. 11 In many countries primary hospital teams include physician assistants as well as doctors. Family physicians are usually trained to work in this context as well as primary care and need to have extended skills in obstetrics, surgery, and anesthetics. 12 For example, the physicians must be able to perform a Caesarean section, operate for an ectopic pregnancy, or perform an amputation, and provide general anesthesia for patients classified as lower risk by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA 1 and sometimes 2).

General practitioners and family physicians may also work in the private sector and serve the smaller proportion of the population that has medical insurance or can afford a fee-for-service. 13 In this context, care looks similar to that of general practice in high income countries. Several countries in the region also rely on private-not-for-profit health services that are typically run by faith-based organizations.

Family medicine training is more likely to be found in English-speaking countries, and a much weaker tradition of family medicine is found in French- or Portuguese-speaking countries. 1 Nevertheless, Angola has recently embraced family medicine at scale with strong government support and assistance from Cuba and Brazil. 14 The concept of postgraduate training for family or general practice was initially introduced to English-speaking countries from models found in the United Kingdom or Canada. In French-speaking countries, the “médecins généralistes communautaires” program trains doctors for primary care in rural areas over 4 to 8 weeks, but they do not have a tradition of longer postgraduate training. 15

In some countries, such as Nigeria and Ghana, family physicians are more often found in tertiary hospitals than primary care. Departments of family medicine run general outpatient services in such hospitals.

Advocating for Family Medicine Education and Training

Four key stakeholders need to be convinced of the need for family medicine education and training. 16 These are the higher education and training institutions, the registration body for medical practitioners, the government’s department of health, and other health professions. Stakeholders may be unfamiliar with the concept of family medicine or believe that the model seen in high income countries is not feasible in Africa. 17 Higher education and registration bodies often are dominated by other disciplines that may not understand the contribution of family physicians in their respective health systems. In addition, private practitioners from other disciplines may feel threatened by the introduction of family physicians because their scope of practice inherently extends into various speciality areas. 18 The private sector also needs advocacy because family physicians with postgraduate training may not be recognized or receive appropriate remuneration.

The department of health must be convinced that a role for family physicians exists in the health system and that this role can be taken to scale with available resources. 19 Family physicians themselves must strive to be relevant in addressing the local health system’s needs. In recent years both Kenya and Angola have embraced such a vision for their countries. 14, 20

Evidence of Impact

Effective advocacy requires an evidence base to make a convincing argument to policymakers. Much of the evidence for the impact of family physicians comes from high-income countries and may be quite old. 21 Governments in sub-Saharan Africa may not be swayed by such evidence because it comes from different health systems and levels of resources. In many countries, the small numbers of family physicians and absence of big data makes producing convincing evidence difficult. 9 Studies in South Africa have suggested that family physicians make an impact across all their roles in the public health system and that this impact is significantly greater than a medical officer without postgraduate training. 22, 23

Studies suggest that the roles of the family physician can be summarized into three key areas. 12, 24 Firstly, as a clinician and consultant, the family physician offers direct patient care and brings more comprehensive and extended services closer to the community. As a consultant, the family physician sees more complex patients referred from their health care team while providing support and feedback. Family physicians also may provide the confidence that team members need to use all their skills, knowing that a more senior person is available should help be needed. 25 Secondly, they have an important role in capacity building, clinical training, and creating a learning environment for the whole facility. Capacity building is focused on the learning needs of the team, while clinical training is focused on students. In some settings, undergraduate students, registrars, physician assistants, and interns may be placed under their supervision. Thirdly, they have a role in leading clinical governance for the team and services. They may be instrumental in setting up systems to improve quality, ensure patient safety, build resilience, and enable performance management. Specific activities could include implementing guidelines, leading audit and feedback, facilitating morbidity and mortality meetings, reporting patient safety incidents, or enabling reflection on routinely collected data. All these roles can be applied in primary care or primary hospitals. In sub-Saharan Africa, the implementation of primary health care is sometimes described as community-orientated primary care with an emphasis on community participation and stakeholder engagement. 26 In South African studies, the district managers report that family physicians are an effective intervention to strengthen district health services. 27

Barriers and Enablers to Implementation

The barriers and enablers to family medicine training have been identified in terms of country- or institution-related stages of change: 16

-

Precontemplation: The country or institution is not considering family medicine training soon (eg, Rwanda, Benin).

-

Contemplation: Key stakeholders are discussing the idea of introducing family medicine training (eg, Tanzania public sector, Namibia).

-

Action: Family medicine training is planned or has started but without any or few graduates (eg, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Lesotho, Somaliland).

-

Maintenance and scale up: Family medicine training is established but needs to be sustained and go to scale (eg, South Africa, Kenya, Botswana, Uganda, Ghana, Nigeria, Malawi, DRC).

When a country is contemplating family medicine training, then a need usually exists to overcome scepticism or doubt from at least one of the key stakeholders. 28 Even when all stakeholders agree there is often considerable inertia in implementing decisions.

Political support for strengthening primary care and family medicine is also a key aspect. Seven principles for effective advocacy with government include understanding the political and health context, identifying the right stakeholders to engage with, building collaborative relationships, using evidence and data, having a clear message, engaging the public, and using media effectively. 29

When taking action to implement family medicine training, key barriers include a small number of inexperienced academic family physicians. To design a curriculum for the local context, aligning the expected roles of the family physician with programmatic outcomes, determining content and forms of assessment, developing educational resources, and deciding on teaching methods are all challenging and novel tasks. Training institutions therefore need to prioritize training academic family physicians, have clear professional development plans, and advocate for positions in the university.

In addition, the training program requires effective clinical trainers in the workplace to supervise students. 30 Often such trainers are absent, difficult to retain, or inexperienced. Programs often start by relying on training from other specialists or international family physicians coming from high-income countries. 31 This approach usually implies that registrars are trained in the wrong context by people who do not fully understand their learning needs or required outcomes. Zambia, for example, despite having a fully developed and approved curriculum, delayed the commencement of its program for close to 2-years because the country did not have any family medicine faculty. Eventually, the program started without training by family physicians, with people who had only a modest understanding of family medicine and its contribution to primary care. Creating reliable and valid forms of assessment for progression in the program or national licensing is also difficult.

Once a program has several graduates, the health system needs to create posts in appropriate settings and to understand the contribution of family physicians. 24 Government policies, such as on human resources for health, need to reflect understanding of the role of family physicians. For example, in South Africa, the government human resources for health policy underestimated the number of family physicians needed by seeing them as specialists in tertiary hospitals rather than in district-level services. 32 Such policy should set clear goals for the number of family physicians needed. Resources allocated to the health sector also may be inadequate to strengthen the system and implement new initiatives. 33 While national government sets policy, the state or province often decides allocation of the budget and which policies are actively implemented. Implementation also may be hindered by corrupt or incompetent managers. The training programs need to mature and ensure that training can happen by family physicians with educational skills in the appropriate primary care or hospital setting.

To go to scale in a reasonable timeframe, enough funded training posts or scholarships must be available to support registrars. Creating training posts in district health services is a break from the traditional tertiary hospital setting for training medical specialists. This approach requires additional advocacy and explanation at various levels in the department of health.

The PRIMAFAMED (Primary Care and Family Medicine) network includes 40 departments of family medicine from 25 countries. 34 It has been instrumental in sharing educational ideas and resources, supporting new programs, and harnessing the power of South-South-North collaboration. Most recently, the network enabled the launch of the East, Central, and Southern African College of Family Physicians. 35 This college intends to catalyze and improve the quality of family medicine training in the region.

Implementation Strategies

Different implementation strategies have been used to overcome the barriers or leverage enablers. The range of strategies and examples are given in Table 2 according to a recent typology. 36 This typology identified 68 potential generic implementation strategies across six categories: planning, educational, financial, restructuring, managing quality, and the policy context.

|

Category of strategy |

Strategy |

Examples |

Stage of change |

|

Planning |

Conduct local assessment of need, readiness, and barriers. |

Qualitative studies to explore perceptions of stakeholders, local needs, and barriers 18, 27, 28 |

Contemplation |

|

|

Tailor strategies to barriers and preferences. |

An initial focus on family physicians filling a skills gap in district hospitals that was important to the DOH enabled deployment of family physicians in the Western Cape. 37 |

Contemplation |

|

|

Conduct discussions with key stakeholders. |

The South-South twinning project within PRIMAFAMED twinned departments from South Africa with departments from other countries to support their development. 38 |

Contemplation |

|

|

Identify and prepare champions. |

In Botswana, family medicine was championed by a public health specialist and an ophthalmologist. |

Contemplation |

|

|

Academic partnerships |

Ethiopia has developed through a partnership between the University of Addis Ababa and University of Toronto.39 |

Contemplation-maintenance |

|

|

Resource sharing |

The Leboha (Lesotho-Boston Alliance) program in Lesotho shared its multiple-choice examination questions with the National University of Science and Technology in Zimbabwe to enable the licensing exam to go ahead. |

Action |

|

|

Build a coalition. |

Universities in 10 countries came together to form the East-Central-Southern African College of Family Physicians. The aim is to share expertise and resources to create valid and reliable assessment and to increase opportunities for training. 35 |

Action |

|

Educate |

Develop effective education materials. |

Design and development of a national portfolio of learning for workplace-based assessment 40 |

Action |

|

|

Distribute materials. |

Development of web-based educational modules that enable access to a consistent educational approach across training complexes in different locations 41 |

Action |

|

|

Educational meetings and ongoing training |

Development of workplace-based training and assessment through the creation of entrustable professional activities and e-portfolios 42, 43 |

Action |

|

|

Train the trainers. |

National course to train clinical trainers and develop a cadre of people who can deliver the course 30 |

Maintenance |

|

|

Provide ongoing consultation. |

Formative assessment visits to training sites to improve the learning environment and development of the clinical trainer 44 |

Maintenance |

|

|

Learning collaborations |

Share educational innovations and expertise via an institutional network of departments of family medicine and primary care (PRIMAFAMED), and through annual meetings and e-workshops. 34 |

Maintenance |

|

|

Inform and influence stakeholders. |

Continue to inform and influence key stakeholders via media, position papers, policy briefs, meetings, and participation in working groups. 24 |

Maintenance |

|

Finances |

Modify incentives. |

Ensure that family physicians are paid the equivalent of other specialists. |

Action |

|

|

Use other payment schemes. |

Engage with the private sector to ensure family physicians are remunerated appropriately according to their scope of practice. |

Maintenance |

|

Restructure |

Revise professional roles. |

Clarify the roles of the family physician in the health system. The roles are clinician, consultant, capacity builder, clinical trainer, and leader of clinical governance, and may also manage people and resources. 24 |

Action |

|

|

Create new clinical teams. |

Clarify the placement of family physicians in clinical teams in primary care, district hospitals, and the district. |

Action |

|

Quality management |

Develop and organize quality monitoring systems. |

Collect qualitative and quantitative data on the effect of family physicians on quality of care and service delivery. 22 |

Maintenance |

|

|

Develop tools for quality monitoring. |

Development of the Family Physician Impact Assessment Tool 45 |

Maintenance |

|

|

Use advisory boards and work groups. |

Coordination of the quality of training across all institutions by a national Education and Training Committee under the national professional body |

Maintenance |

|

|

Purposefully reexamine implementation. |

Evaluation of the experience of registrars with the research assignment in order to improve research teaching and supervision 46 |

Maintenance |

|

|

Capture and share local knowledge. |

A call for short reports on educational innovations in the African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine |

Maintenance |

|

Attend to policy context |

Change accreditation or membership requirements. |

Introduction of national accreditation of expertise in clinical training 47 |

Maintenance |

|

|

Create or change credentialing and/or licensure standards. |

Ensure that family physicians can be registered as specialists with clear criteria. |

Action |

Abbreviations: DOH, department of health; PRIMAFAMED, Primary Care and Family Medicine

Family medicine education and training is gaining traction with health systems in sub-Saharan Africa, although the extent of development varies widely among countries. Networks such as PRIMAFAMED can enable South-South collaboration within the region, but strategic partners from high-income countries are also needed. Key lessons for developing such partnerships are to share a vision and goals, build commitment and trust, have respect for the cultural context, strengthen sustainable local capacity, allow bidirectional knowledge flows, be responsive and flexible to changing circumstances, and persist even in adversity. 39 We hope that in the future family medicine in Africa will make an even more significant contribution to high-quality primary health care and universal health coverage in the region.

References

-

Wilfrid Laurier University. Exploring global family medicine. Accessed April 19, 2022. https://globalfamilymedicine.org

-

Mash R, Besigye I, Galle A. Undergraduate teaching in family medicine within the PRIMAFAMED network. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2024;16(1):a4376. doi:10.4102/phcfm.v16i1.4376

-

Ministère de la santé Publique. Plan National de Développement Sanitaire recadré pour la période 2019-2022: Vers la couverture sanitaire universelle. December 2021. Accessed August 6, 2024. https://sante.gouv.cd/content/uploads/RAPPORT_CNS_2020_86e645c64a.pdf

-

Mash R, Malan Z, Von Pressentin K. Strengthening primary health care through primary care doctors: the design of a new national Postgraduate Diploma in Family Medicine. South African Family Practice. 2016; 58(1):32-36. Doi: 10.1080/20786190.2015.1083719

-

Wilfrid Laurier University. Exploring global family medicine. Accessed April 19, 2022. https://globalfamilymedicine.org

-

Von Pressentin KB, Besigye I, Mash R, Malan Z. The state of family medicine training programmes within the Primary Care and Family Medicine Education network. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2020;12(1):e1-e5. doi:10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2588

-

Mash R, Downing R, Moosa S, De Maeseneer J. Exploring the key principles of family medicine in sub-Saharan Africa: international Delphi consensus process. S Afr Fam Pr. 50(3):60–5. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/20786204.2008.10873720

-

Mash R, Howe A, Olayemi O, et al. Reflections on family medicine and primary healthcare in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3:e000662. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000662

-

Flinkenflögel M, Sethlare V, Cubaka VK, Makasa M, Guyse A, De Maeseneer J. A scoping review on family medicine in sub-Saharan Africa: practice, positioning and impact in African health care systems. Hum Resour Heal. 2020;18:1-18. doi:10.1186/s12960-020-0455-4

-

Tiwari R, Mash R, Karangwa I, Chikte U. A human resources for health analysis of registered family medicine specialists in South Africa: 2002–19. Fam Pract. 2021;38(2):88-94. https://academic.oup.com/fampra/advance-article/doi/10.1093/fampra/cmaa084/5904030 doi:10.1093/fampra/cmaa084

-

De Villiers M, De Villiers P. The knowledge and skills gap of medical practitioners delivering district hospital services in the Western Cape, South Africa. S Afr Fam Pract. 2006;48(2):16-16c. doi:10.1080/20786204.2006.10873333

-

Besigye IK, Onyango J, Ndoboli F, Hunt V, Haq C, Namatovu J. Roles and challenges of family physicians in Uganda: a qualitative study. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2019;11(1):e1-e9. doi:10.4102/phcfm.v11i1.2009

-

Mohamoud G, Mash R. The quality of primary care performance in private sector facilities in Nairobi, Kenya: a cross-sectional descriptive survey. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23:120. doi:10.1186/s12875-022-01700-3

-

Avelino IC, Chimuco KSM, Díaz NT, Jantsch AG. Don’t wait for the perfect moment: the national training program in family medicine in Angola. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2024;16(1):e1-e4. doi:10.4102/phcfm.v16i1.4458

-

Bello K, De Lepeleire J, Kabinda M J, et al. The expanding movement of primary care physicians operating at the first line of healthcare delivery systems in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0258955. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258955

-

Mash RJ, de Villiers MR, Moodley K, Nachega JB. Guiding the development of family medicine training in Africa through collaboration with the Medical Education Partnership Initiative. Acad Med. 2014;89(8):S73-S77. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000328

-

Moosa S, Downing R, Essuman A, Pentz S, Reid S, Mash R. African leaders’ views on critical human resource issues for the implementation of family medicine in Africa. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12(1):2. doi:10.1186/1478-4491-12-2

-

Sururu C, Mash R. The views of key stakeholders in Zimbabwe on the introduction of postgraduate family medicine training: a qualitative study. African J Prim Heal Care Fam Med. 2017;9(1):a1469. doi:10.4102/phcfm.v9i1.1469

-

Fina-Lubaki JP, Mudji E’kitiak J, Lukanu Ngwala P. Primary healthcare training in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2024;16(1):e1-e3. doi:10.4102/phcfm.v16i1.4508

-

Momanyi K, Dinant GJ, Bouwmans M, Jaarsma S, Chege P. Current status of family medicine in Kenya; family physicians’ perception of their role. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2020;12(1):e1-e4. doi:10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2404

-

Shi L, Starfield B, Politzer R, Regan J. Primary care, self-rated health, and reductions in social disparities in health. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(3):529-550. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.t01-1-00036

-

Mash R, von Pressentin K. Strengthening the district health system through family physicians. S Afr Health Rev. 2018;33-39.

-

von Pressentin KB, Mash RJ, Baldwin-Ragaven L, et al. The perceived impact of family physicians on the district health system in South Africa: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):24. doi:10.1186/s12875-018-0710-0

-

South African Academy of Family Physicians. The contribution of family physicians to district health services in South Africa: a national position paper by the South African Academy of Family Physicians. SA Fam Pr. 2022;64(1):5473.

-

Mash R. The contribution of family physicians to African health systems. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2022;14(1):e1-e9. doi:10.4102/phcfm.v14i1.3651

-

Mash B, Ray S, Essuman A, Burgueño E. Community-orientated primary care: a scoping review of different models, and their effectiveness and feasibility in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(suppl 8):e001489. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001489

-

Von Pressentin K, Mash R, Baldwin-Ragaven L, Botha R, Govender I, Steinberg W. The bird’s-eye perspective: how do district health managers experience the impact of family physicians within the South African district health system? a qualitative study. S Afr Fam Pract. 2018;60(1):13-20. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/20786190.2017.1348047 doi:10.1080/20786190.2017.1348047

-

Ogundipe RM, Mash R. Development of family medicine training in Botswana: views of key stakeholders in Ngamiland. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2018;7(1):e1-e9.

-

Mash R, Von Pressentin K, Nash J, Ras T. Lessons learnt from advocating for family medicine in South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2024;17(1):a4795.

-

Brits H. A national training course for clinical trainers in family medicine. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2024;16(1):e1-e3. doi:10.4102/phcfm.v15i1.4341

-

Ross JM. General practice training in Uganda. Part 1: Setting, personnel, and facilities. Can Fam Physician. 1996;42:213-216.

-

National Department of Health. 2030 Human Resources for Health Strategy: Investing in the Health Workforce for Universal Health Coverage. Government Printers; March 2020

-

Mash B. World Health Day: SA’s public health sector facing crisis amid budget cuts. Mail and Guardian. April 7, 2024. https://mg.co.za/thought-leader/opinion/2024-04-07-world-health-day-sas-public-health-sector-facing-crisis-amid-budget-cuts

-

PRIMAFAMED. Website. Accessed June 23, 2022. https://primafamed.sun.ac.za

-

Ray S, Madzimbamuto FD. Proposal to set up a college of family medicine in East, Central and Southern Africa. African J Prim Heal Care Fam Med. 2022;14(1):a3612. https://phcfm.org/index.php/phcfm/article/view/3612/5582

-

Powell BJ, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, et al. A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69(2):123-157. doi:10.1177/1077558711430690

-

Jenkins L, Mash B, Derese A. Development of a portfolio of learning for postgraduate family medicine training in South Africa: a Delphi study. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13(1):11. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-13-11

-

West African College of Physicians. Faculty of family medicine e-learning courses. Accessed August 15, 2024. https://www.evidemy.com

-

Mash R, Jenkins L, Naidoo M. Development of entrustable professional activities for family medicine in South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2024;16(1):a4483. doi:10.4102/phcfm.v16i1.4483

-

Jenkins L, Mash R, Naidoo M, Motsohi T. Developing an electronic portfolio of learning for family medicine training in South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2024;16(1):e1-e4. doi:10.4102/phcfm.v16i1.4525

-

Woldeyes MZ, Makhani L, Ephrem N, et al. Pioneering family medicine: a collaborative global health education partnership in Ethiopia. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2024;16(1):e1-e5. doi:10.4102/phcfm.v16i1.4599

-

Mash R, Malan Z, Blitz J, Edwards J. Improving the quality of clinical training in the workplace: implementing formative assessment visits. S Afr Fam Pract. 2019;61(6):264-272. doi:10.1080/20786190.2019.1647639

-

Pasio KS, Mash R, Naledi T. Development of a family physician impact assessment tool in the district health system of the Western Cape Province, South Africa. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15(1):204. doi:10.1186/s12875-014-0204-7

-

Louw E, Mash RJ. Registrars’ experience with research in family medicine training programmes in South Africa. S Afr Fam Pract. 2024;66(1):e1-e12. doi:10.4102/safp.v66i1.5907

-

South African Academy of Family Physicians. Accreditation of clinical trainers in family medicine. Accessed August 6, 2024. https://saafp.org/ctaccreditation

-

Mash B. Reflections on the development of family medicine in the Western Cape: a 15-year review. S Afr Fam Pract. 2011;53(6):557-562. doi:10.1080/20786204.2011.10874152

-

De Maeseneer J. Twenty years of PRIMAFAMED network in Africa: looking back at the future. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2017;9(1):e1-e2. doi:10.4102/phcfm.v9i1.1603

Lead Author

Robert Mash, PhD

Affiliations: Division of Family Medicine and Primary Care, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa

Co-Authors

Innocent Besigye, PhD, MMed - Department of Family Medicine, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

Akye Essuman, FWACP - Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Health & Allied Sciences, Ho, Ghana

Jean-Pierre Fina Lubaki, PhD - Department of Family Medicine and Primary Care, Protestant University of Congo, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Mpundu Makasa, PhD - Department of Community and Family Medicine, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia

Martha Makwero, PhD, MMed - Department of Community and Family Medicine, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia

Gulnaz Mohamoud, PhD - Department of Family Medicine, Aga Khan University, Nairobi, Kenya

Corresponding Author

Robert Mash, PhD

Correspondence: Division of Family Medicine and Primary Care, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa

Email: rm@sun.ac.za

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.