Background and Objectives: The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) International Medical Graduate (IMG) program addresses the need for more bilingual and bicultural Latino family physicians in California where Latinos are the largest racial/ethnic minority group and a large percentage of the population speaks Spanish. The objective of this descriptive study was to assess family medicine residency match, board certification, and initial practice location outcomes of the program graduates.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study of program graduates (N=204) from 2007 to 2024. Data were abstracted from program administrative files and the California Medical Board. Primary outcomes were match rate into California family medicine residency programs, completion of a residency, board certification, and initial training practice location. We computed descriptive statistics for participant characteristics and outcomes.

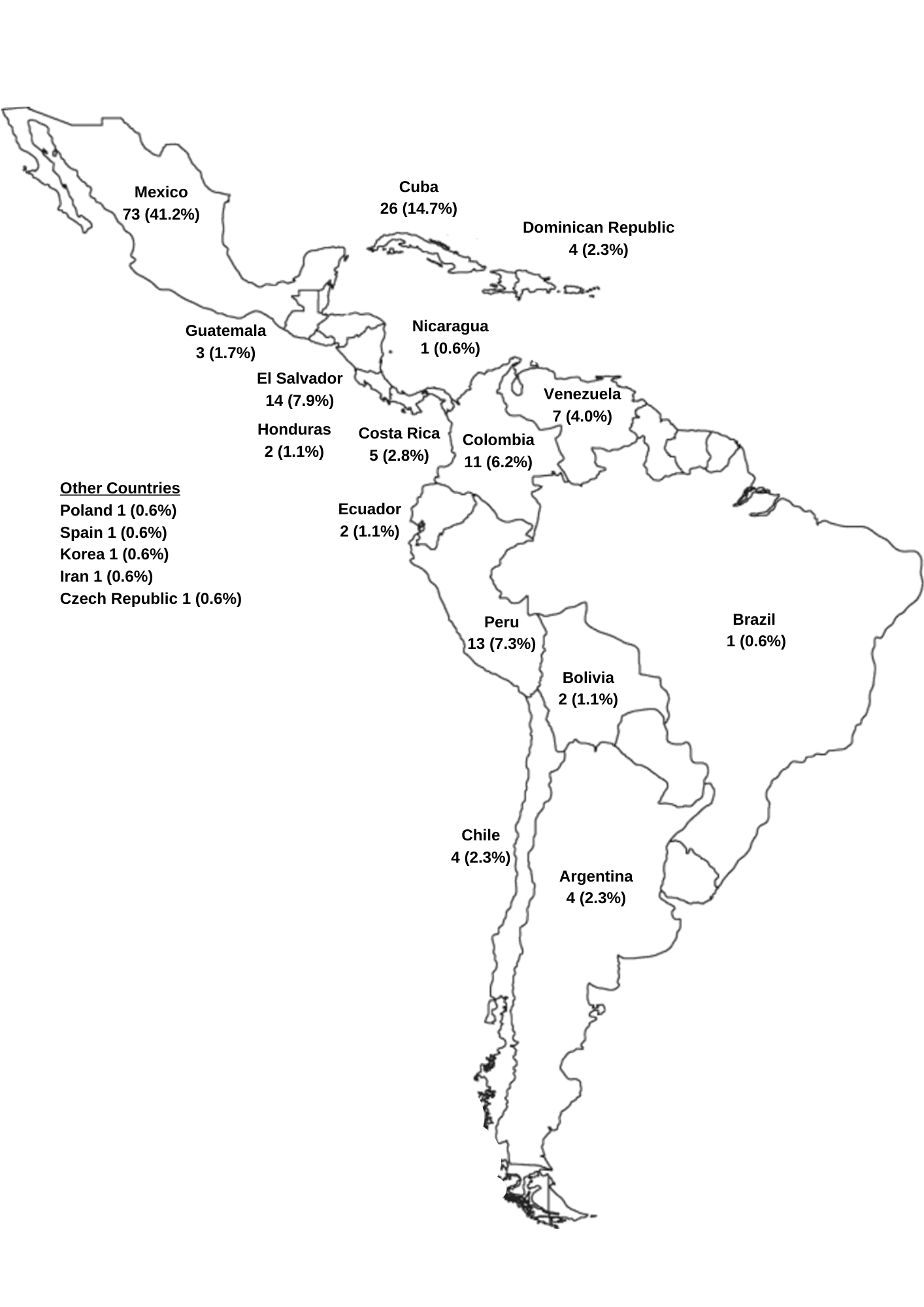

Results: A total of 177/204 (87%) participants completed the UCLA IMG program and entered the match. The country with the most graduates was Mexico followed by Cuba. All graduates, 177/177 (100.0%), that applied and entered the National Resident Matching Program matched in a family medicine residency program. A total of 172 (97%) matched in California programs and 5 (2.8%) matched out of state. Family medicine board certification was verified for 152/159 (95.6%) of those eligible. Few completed a fellowship.

Conclusions: The UCLA IMG program was effective at preparing program graduates that were fluent in Spanish and bicultural to match in a California family medicine residency program and subsequently practice family medicine in underserved areas. Future studies will examine long-term practice outcomes, predictors of success, and participant perspectives on the program.

Latinos in the United States have grown to 63.7 million, representing 18.9% of the total population and making up the nation’s second largest racial/ethnic group after non-Latino White individuals. 1 In fact, by 2050, one in four Americans will be Latino. 2, 3 More than two-thirds of Latinos report speaking a language other than English at home, highlighting the diverse language needs of this group. 1 Latinos with limited English proficiency face barriers to receiving high-quality medical care and report lower satisfaction with provider communication than English-speaking patients. Patients who are matched with language-concordant physicians are more satisfied with their medical care, bond with their physician, and receive a higher quality of care. 4, 5 These language barriers contribute to health care disparities and call for more bilingual and bicultural primary care physicians.

Despite efforts to increase diversity in the physician workforce, only 6% of practicing physicians in the United States 6 and 6.8% of board certified family physicians identify as Latino. 7 A shortage of Latino resident physicians also exists. 8 Efforts to address this need have focused on early exposure programs, pathway programs, advocacy for increased primary care residencies, and expansion of international medical graduate (IMG) placements in workforce shortage areas. 9 IMGs are physicians who completed medical education outside the United States and includes both US-born individuals who choose to attend medical schools abroad and individuals who are foreign-born and educated. 10

Research shows that IMGs born in Latin American countries are likely to choose their practice locations based on ethnic matching. 10 Among board certified family physicians, 23% are IMGs, and this percentage mirrors the national estimates of IMGs among all physicians. 7 IMGs play a critical role in addressing health care shortages and maldistributions, and also the need for bilingual physicians. In fact, many states have implemented novel IMG programs to address areas with physician shortages. Nine states have approved IMG legislation, and 19 states have pending legislation that would facilitate full licensure practice pathways without postgraduate training for IMGs. 11, 12 Additionally, three states enacted limited licensure pathways. Some include provisions or requirements for practice in underserved areas. However, to our knowledge, pathways are limited that offer the necessary support and opportunities for completing postgraduate residency training and American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) certification for family physicians. The Federation of State Medical Boards tracks states with enacted and proposed additional full or limited licensure pathways without accredited North American postgraduate training. 13

To increase the number of bilingual, bicultural Latino/a family physicians in California, the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Department of Family Medicine developed a novel program in 2006 for physicians who had emigrated from Latin America but were not licensed to practice medicine in the United States. 14 The objective of this study was to assess participant characteristics and describe family medicine residency match, board certification, and initial practice outcomes of the UCLA IMG program.

Program Description

Developed in 2006, the preresidency training IMG program is designed to prepare more family physicians to practice in medically underserved California communities. The program, cofounded by P.T.D. and M.B., aims to accomplish this goal by recruiting international medical graduates and providing them with a rigorous professional education and hands-on clinical experiences to compete and match in a California family medicine residency program. 14 A graduate of the program (B.S.C.) is now the program director. The UCLA IMG program requires full-time participation, residence in Los Angeles County, no outside employment, English and Spanish language fluency, and US citizenship or permanent resident legal status. The program is currently free of tuition or fees, covers educational expenses, and includes a small stipend.

Prior to passage of Assembly Bill 1533, state law prevented IMG trainees from participating in supervised clinical contact with patients because they weren’t recognized as residents or medical students enrolled in a school of medicine. 15

As a result, initially the curriculum also focused on how to best prepare participating IMGs to successfully pass the United States Medical Licensing Examinations (USMLE) and improve professional-level English oral and writing skills.

Through passage of California legislation in 2012, the California Medical Board authorized the following program requirements to allow participants to receive hands-on clinical instruction: (a) graduation from a medical school recognized by the California Medical Board (recognition by the World Federation for Medical Education and the Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research); (b) Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) certification; (c) passing score for the USMLE Step 1 and 2; and (d) permanent legal US residency status. The state medical board also requires clinical instruction to take place at health care facilities operated by UCLA or other approved UCLA-designated teaching sites with a formal affiliation agreement. Finally, faculty at UCLA or faculty affiliated with UCLA are required to provide the clinical instruction and supervision. Upon completing family medicine residency training, graduates are contractually required to practice family medicine for a minimum of 2 years in a medically underserved community in California.

Curriculum

The curriculum was developed to support participating IMGs to successfully prepare an application to a California family medicine residency training program by providing a clinical hands-on experience in underserved clinical settings and opportunities to learn the language and culture of US medicine. During their training, participants perform patient interviews, conduct assessments, develop treatment plans, draft clinical notes, and present cases to licensed supervising UCLA faculty physicians. This hands-on experience is like that of a medical student involved in patient care while adhering to the medical board supervision and training standards. The curriculum includes a required medical English course. In 2009, the clinical curriculum increased from 8 weeks to 12 weeks (6 weeks hospital and 6 weeks primary care); and in 2010, the outpatient curriculum expanded to include the core concepts of the patient-centered medical home. Participants also are required to complete a course and obtain HIV specialist (American Academy of HIV Medicine) certification. Within the program, clinical training does not exceed 16 weeks of clinical instruction, and all clinical experiences are in underserved settings at UCLA affiliates.

Upon completion of the program, UCLA program directors provide a letter of recommendation for family medicine residency match applications. The letter includes Occupational English Test information and clinical evaluations by UCLA faculty using Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education rubrics for family medicine.

Analysis

We abstracted data from program administrative files of 204 program participants and analyzed cross-sectional data from 2007 to 2024. Data availability was limited between 2006 and 2012 for 27 participants who did not advance and complete the program. Data abstracted from the program application include age, gender, language spoken, race/ethnicity, immigration status, country of origin, and international medical school. Data abstracted from the Medical Board of California public website includes training status, primary and secondary practice zip codes, and self-reported board certification. Primary outcomes were successful matching in a California family medicine residency program, completion of a family medicine residency, licensure, American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) board certification, and practice location. Residency practice training location was stratified by health professional shortage area (HPSA) designations. We identified residents who were not yet eligible for board certification or medical licensure. We excluded these residents, as indicated from our calculations of graduates who are board certified and/or holding an active medical license. We computed descriptive statistics for participant characteristics and outcomes. The study was an institutional review board exempt by UCLA. R version 4.4.1 (R Project) was used for all data analysis.

From 2006 to 2024, a total of 177/204 (87%) participants completed the UCLA IMG program and entered the match. Enrollment has ranged from 4 to 21 physicians. Between 2006 and 2012, 27 participants did not advance (n=25) or withdrew (n=2) due to not passing USMLE Step 1 or 2. Program attrition was observed only among those accepted without passing USMLE Step 1 and/or 2 and was 27/88 (31%). Starting in 2012, a passing score for USMLE was required for acceptance, and no attrition has taken place since then. Table 1 describes demographic characteristics, gender, language(s) spoken, ethnicity, and country of origin. All program participants were fluent in Spanish and were US permanent residents or citizens. The country with the most graduates was Mexico, followed by Cuba (Figure 1).

|

Participant

characteristics

|

n (%)

|

|

Gender, n=177

|

|

|

Female

|

81 (45.8)

|

|

Male

|

96 (54.2)

|

|

Spanish language fluency, n=177

|

177 (100.0)

|

|

Latino/a ethnicity, n=177

|

166 (93.8)

|

|

Medical school graduation year, n=174

|

|

|

1995–2000

|

9 (5.2)

|

|

2001–2005

|

38 (21.8)

|

|

2006–2010

|

65 (37.4)

|

|

2011–2015

|

45 (25.9)

|

|

2016–2021

|

17 (9.8)

|

|

Country of origin, n=168

|

|

|

Argentina

|

4 (2.4)

|

|

Bolivia

|

2 (1.2)

|

|

Chile

|

3 (1.8)

|

|

China

|

2 (1.2)

|

|

Colombia

|

11 (6.5)

|

|

Costa Rica

|

3 (1.8)

|

|

Cuba

|

21 (12.5)

|

|

Dominican Republic

|

3 (1.8)

|

|

Ecuador

|

2 (1.2)

|

|

El Salvador

|

12 (7.1)

|

|

Germany

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

Guatemala

|

3 (1.8)

|

|

Haiti

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

Honduras

|

2 (1.2)

|

|

Korea

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

Mexico

|

54 (32.1)

|

|

Nicaragua

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

Panama

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

Peru

|

13 (7.7)

|

|

Puerto Rico

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

Spain

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

United States

|

22 (13.1)

|

|

Venezuela

|

4 (2.4)

|

Table 2 shows the percentage of program graduates that matched into a family medicine residency program and those that are ABFM certified. The program has placed 177 graduates into US family medicine residency programs. All graduates 177/177 (100.0%) that have applied and entered the National Resident Matching Program matched in a family medicine residency program. Of these, 172 (97%) matched in California residency programs and 5 (2.8%) matched in out of state programs. Among program graduates that matched, 157/177 (89%) completed residency training and 18/177 (10%) were in training. The majority of those eligible for medical licensure had a verified medical license (98.8%). ABFM board certification was verified for 152/159 (95.6%) of those eligible. Less than 10% of those that completed residency also completed an ABMS sponsored fellowship. Among the 177 participants, 62.1% trained in California urban HPSAs, 35.0% in California rural HPSAs, and 2.8% out of state.

|

Graduate medical education outcomes

|

n (%)

|

|

Matched in a family medicine residency, N=177

|

|

California residency program

|

172 (97.2)

|

|

Non-California US residency program

|

5 (2.8)

|

|

Practice and training status

n=177

|

|

Practicing, not in training

|

157 (88.7)

|

|

In training, residency

|

18 (10.2)

|

|

Unknown

|

2 (1.1)

|

|

Active US medical licensure*

n=165

|

|

State of California medical licensure

|

150 (90.9)

|

|

Other US state medical licensure

|

13 (7.9)

|

|

Unknown

|

2 (1.2)

|

|

ABFM board certification**

n=159

|

152 (95.6)

|

|

Completed ACGME accredited fellowship,

n=159

|

13 (8.2)

|

|

Geriatrics

|

6 (3.8)

|

|

Primary care sports medicine

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

Addiction medicine

|

6 (3.8)

|

|

Completed other fellowship ***

n=159

|

1 (0)

|

|

HPSA training location

n=177

|

|

|

California urban HPSA

|

110 (62.1)

|

|

California rural HPSA

|

62 (35.0)

|

|

Out of state

|

5 (2.8)

|

Table 3 lists the family medicine residency programs where graduates of the UCLA IMG program successfully matched. The program with the highest number of matches is UCLA, followed by Riverside and Clinica Sierra Vista in Kern County.

|

Name of family medicine residency program (N=177)

|

n (%)

|

|

UCLA Family Medicine Residency

|

26(14.7)

|

|

Riverside University Health System/UCR Family Medicine Residency Program

|

16 (9.0)

|

|

Rio Bravo Family Medicine Residency Program (Clinica Sierra Vista)

|

15 (8.5)

|

|

Dignity Health Hanford Family Medicine Residency Program

|

12 (6.8)

|

|

Pomona Valley Hospital Medical Center Family Medicine Residency Program

|

11 (6.2)

|

|

California Medical Center USC Family Medicine Residency Training Program

|

9 (5.1)

|

|

Dignity Health Northridge Family Medicine Residency Program

|

8 (4.5)

|

|

San Joaquin General Hospital Family Medicine Residency Program

|

8 (4.5)

|

|

UCSF-Fresno Family Medicine Residency

|

7 (4.0)

|

|

Glendale Adventist Health Family Medicine Residency Training Program

|

6 (3.4)

|

|

Natividad Medical Center Family Medicine Residency Program

|

6 (3.4)

|

|

Citrus Valley Health Partners Family Medicine Residency Program

|

5 (2.8)

|

|

Valley Health Team Family Medicine Residency Training Program, Fresno

|

5 (2.8)

|

|

Kaiser Permanente Fontana Family Medicine Residency Training Program

|

3 (1.7)

|

|

Mission Community Hospital Family Medicine Residency

|

3 (1.7)

|

|

Saint Agnes Care Family Medicine Residency Program

|

3 (1.7)

|

|

UCSD Family Medicine Residency Program

|

3 (1.7)

|

|

Dignity Health California Hospital Medical Center Family Medicine Residency

|

2 (1.1)

|

|

Eisenhower Medical Center Family Medicine Residency

|

2 (1.1)

|

|

Family Health Centers of San Diego Family Medicine

|

2 (1.1)

|

|

Harbor-UCLA Family Medicine Residency Training Program

|

2 (1.1)

|

|

Kaweah Delta Family Medicine Residency Program

|

2 (1.1)

|

|

Kern County Medical Center/Bakersfield Family Medicine Residency Program

|

2 (1.1)

|

|

Presbyterian Intercommunity Hospital Family Medicine Residency Program

|

2 (1.1)

|

|

Southwest Healthcare Med Ed Consortium Family Medicine Residency, Temecula

|

2 (1.1)

|

|

UCI Family Medicine Residency Program

|

2 (1.1)

|

|

Valley Consortium for Medical Education Family Medicine Program, Modesto

|

2 (1.1)

|

|

Contra Costa Regional Medical Center Family Medicine Residency Program

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

Long Beach Memorial Family Medicine Residency Training Program

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

Mercy Merced Family Medicine Residency Program

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

Naval Hospital Camp Pendleton Family Practice Residency Training Program

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

Sutter Health Sacramento Family Medicine Residency Program

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

USC Keck Family Medicine Residency Program

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

St. Joseph’s Hospital Family Medicine*

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

Mayagüez Family Medicine Residency Program (Puerto Rico)*

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

Jackson Memorial Hospital, Family Medicine*

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso Family Medicine *

|

1 (0.6)

|

|

University of Texas Houston Family Medicine Residency Program*

|

1 (0.6)

|

In this study of IMG physicians, we found that the UCLA IMG program was effective at preparing IMG program graduates that were fluent in Spanish and bicultural to match in a California family medicine residency program and subsequently practice family medicine in underserved geographic areas. 14 Like other medical specialties, family medicine falls short in racial/ethnic diversity and does not reflect the diversity of the US or California population. 16, 17, 18 The UCLA IMG program addresses the need for more bilingual and bicultural Latino family physicians in California where Latinos are the largest racial/ethnic minority group and where a large percentage of the population speaks Spanish. Building a diverse family physician workforce should include IMG pathway programs with postgraduate training that address health disparities in diverse disadvantaged communities. Without IMG pathways to practice and other medical education innovations, research has estimated that 92 years of a doubling of matriculating Latino medical students would be required to correct the deficit of Latino physicians. 19

All program graduates successfully matched into family medicine residency programs, with the vast majority (97.2%) training within California. Nearly half (45%) of these graduates are serving in the rural San Joaquin/Central Valley agricultural regions of California, addressing a critical shortage of primary care physicians in these underserved communities. The program also was successful in matching graduates in California family medicine residency programs located in urban and rural HPSAs.

Our study has health equity, workforce, graduate medical education, and primary care policy implications. The UCLA IMG program represents a model pathway program for IMG physicians to seek residency training, ABFM certification, and help mitigating health disparities that arise from the lack of primary care access in underserved areas. While many US states currently are debating legislation authorizing new pathways for IMGs toward licensure and clinical practice in underserved rural and urban areas, 11, 20 the UCLA IMG program is a case study that illustrates how US medical schools and departments of family medicine can develop and innovate programs that provide pathways for IMGs toward board certification and family medicine practice for communities in most need of diverse physicians. States with enacted or proposed legislation creating licensure pathways for primary care practice lack academic family medicine input. This program is unique in that it provides a university sponsored pathway with postgraduate training leading to board certification eligibility, ensuring access to ongoing lifelong learning, ongoing assessment, and quality of care for the public.

Another policy consideration is the brain drain that occurs when IMG physicians from low-income countries migrate to higher-income nations like the United States, worsening health care shortages in their home countries. The UCLA IMG program recruits and trains IMGs already residing in the United States—citizens and permanent residents. By focusing on physicians already in the country, the program avoids contributing to the direct recruitment and brain drain from another country while training physicians to serve in underserved US communities.

This study had limitations. Our study was descriptive, and we acknowledge selection bias among program participants. We did not have a comparison group. The UCLA IMG program requires that graduates practice 2 to 3 years in an underserved California area, and future studies will evaluate long-term practice choices, patient population characteristics, and predictors of success or challenges. Future studies also will include qualitative methods to capture participant perspectives and areas of program improvement. More than half of family physicians practice within 100 miles of their residency program location and within the same state, while California retains 75%. 21 Research has shown that IMGs tend to practice in the same state where they do their graduate medical education training and where they have networks, and that IMGs born in Latin America choose practice locations based on ethnic matching. 10

A major barrier for IMGs to obtain medical licensure and board certification is the limited understanding of the process required to enter a US residency training program. Other barriers include limited English proficiency and limited understanding of the US health care system and graduate medical education, meeting ECFMG requirements, passing the USMLEs, and obtaining an authorized immigration status. The UCLA IMG program directors engage significantly with California family medicine residency directors to enhance overall understanding of the program and answer questions about the content and quality of the required clinical education.

We offer a few recommendations for scaling similar programs in other states. First, academic family medicine programs should begin by conducting comprehensive needs assessments to identify primary care shortages, HPSAs, population needs, and underserved communities. Advocacy also plays a critical role, and family medicine programs should engage in efforts at the state level to inform medical boards and legislators about the importance of postgraduate training. Further, securing philanthropic support is essential for administrating the program. Establishing partnerships with federally qualified health centers can provide IMGs with clinical training opportunities in underserved settings. Finally, developing standardized preresidency curricula focusing on core competencies in family medicine, the US health care system, and culturally responsive care is essential.

In summary, we found that the UCLA IMG program is successful in preparing residency trained ABFM board certified family physicians who can address the linguistic and cultural barriers to care for the growing immigrant population in California from Latin American countries. The UCLA program embraces the opportunity to leverage already trained physicians and prepares them to practice in areas where the need is great for bilingual and bicultural primary care physicians.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge UCLA Health, UniHealth, Kellogg Foundation, and East Bay Kaiser Permanente Community Foundation for their funding support.

References

-

-

-

-

Detz A, Mangione CM, Nunez de Jaimes F, et al. Language concordance, interpersonal care, and diabetes self-care in rural Latino patients.

J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(12):1,650-1,656.

doi:10.1007/s11606-014-3006-7

-

Moreno G, Morales LS.

Hablamos Juntos (Together We Speak): interpreters, provider communication, and satisfaction with care.

J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(12):1,282-1,288.

doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1467-x

-

-

-

Martínez LE, Anaya YBM, Santizo Greenwood S, Diaz SFM, Wohlmuth CT, Hayes-Bautista DE. The Latino resident physician shortage: a challenge and opportunity for equity, diversity, and inclusion.

Acad Med. 2022;97(11):1,673-1,682.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004793

-

Goodfellow A, Ulloa JG, Dowling PT, et al. Predictors of primary care physician practice location in underserved urban or rural areas in the United States: a systematic literature review.

Acad Med. 2016;91(9):1,313-1,321.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001203

-

Polsky D, Kletke PR, Wozniak GD, Escarce JJ. Initial practice locations of international medical graduates.

Health Serv Res. 2002;37(4):907-928.

doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.58.x

-

McElvaney OJ, McMahon GT. International medical graduates and the physician workforce.

JAMA. 2024;332(6):490-496.

doi:10.1001/jama.2024.7656

-

Ramesh T, Horvitz-Lennon M, Yu H. Opening the door wider to international medical graduates: the significance of a new Tennessee law.

N Engl J Med. 2023;389(21):1,925-1,928.

doi:10.1056/NEJMp2310001

-

-

Dowling PT, Bholat MA. Utilizing international medical graduates in health care delivery: brain drain, brain gain, or brain waste? a win-win approach at University of California, Los Angeles.

Prim Care. 2012;39(4):643-648.

doi:10.1016/j.pop.2012.08.002

-

-

Moreno G, Walker KO, Morales LS, Grumbach K. Do physicians with self-reported non-English fluency practice in linguistically disadvantaged communities?

J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(5):512-517.

doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1584-6

-

-

Yoon J, Grumbach K, Bindman AB. Access to Spanish-speaking physicians in California: supply, insurance, or both.

J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17(3):165-172.

doi:10.3122/jabfm.17.3.165

-

-

Andrews JS, Ryan AL, Elliott VS, Brotherton SE. Easing the entry of qualified international medical graduates to U.S. medical practice.

Acad Med. 2024;99(1):35-39.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000005310

-

There are no comments for this article.