THE CHALLENGE: Family medicine departments see elevating equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI)* as socially necessary and as powerful in achieving core missions. The importance and timeliness of this longstanding issue in medicine are magnified by the COVID-19 pandemic with its disproportionate effect on communities of color and by civil unrest focused on racial justice. EDI plays out in three pillars: (1) care delivery and health, (2) workforce recruitment and retention, and (3) learner recruitment and training. People are at very different places with EDI work with regard to knowledge, experience, comfort and confidence. This is a wide-ranging developmental challenge, not a narrow, technical, or quick fix.

The Immediate Goal: To make a strong start in taking all faculty and staff on a participatory journey that brings changes in everything they do, using inclusive means to this inclusive end.

Initial Achievements: An inclusive process that resulted in (1) a shared intellectual framework—definitions with “north star” goals across the three pillars of EDI action, (2) shared acceptance of need for change, (3) top growth areas with actions to take, and (4) harnessing the energy for action—many volunteers, a visible leader, and charge.

Ongoing Action: Application of an equity lens to department relationships, specific incidents, tools and education, policy review, and measures development.

Invitation to Further Conversation Among Departments: EDI work can quickly create a shared intellectual framework and broadly engage people in taking a department down its developmental path. Operating principles for undertaking such work are offered for conversation among departments.

Family medicine departments see that elevating equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI)1 in their institutions is an essential and powerful way to better achieve core missions.1,2 The importance and timeliness of this longstanding issue in medicine are magnified by the COVID-19 pandemic with its disproportionate effect on communities of color,3,4 and by widespread civil unrest focused on racial justice that includes health, employment, and educational equity dimensions.5,6 Calls for action on racial and other types of injustice in medicine have been made for years,7-9 but the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis was a local and unprecedented accelerator for the necessity and widespread buy-in for this work.

This article offers our story of framing and initiating action as a whole family medicine department—for possible benefit to and conversation with others. Our department10 has 98 faculty, eight residency programs, four fellowship programs, plays a large role in medical student education, and has an active research enterprise ranked number three for National Institutes of Health funding among family medicine departments nationally. Our department has programs in health disparities research, sports medicine and in human sexuality. Five residencies in the Twin Cities and three in greater Minnesota produced 55 graduates in 2020. The majority of faculty and residents are White.

Even in context of many positive things in one’s own work environment, honest conversations about racism and other forms of injustice are challenging and sensitive in different ways for different people. Conversations may be difficult because

- Some people have benefited from differential distribution of resources, marginalization of others, unjust systems, policies, and traditions (referred to as privilege) even if they didn’t create them and may not be fully aware of them. They may be the ones most uncomfortable facing this and may “fear making a mistake that might offend others or expose ignorance.”10

- Other people with direct experiences of being disadvantaged by these systems or traditions (often referred to as oppression) welcome this overdue conversation, but may experience invalidation and not being heard as well as feel a desire to back off and lessen discomfort in the room, although this instinct can maintain a harmful status quo.10 They may also be expected to speak as a stand-in for entire groups (eg, Black people or women, rather than the individuals they are). Individuals may experience interlocking disadvantage across social categories (eg, race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status) termed intersectionality.11

- Everyone faces broad scope and complexity, as inequities span care delivery, the workplace, learner education, research; across more than one kind of injustice (eg, race, culture, gender, or sexual orientation, age, urban-rural, or economic background); and with all the new language, insights, and concepts involved.

Yet these vulnerable-feeling conversations must take place, with “a willingness to ‘come step in it’”10 if we are to change awareness, systems, policies, and traditions that have disadvantaged or marginalized groups and individuals. Despite being challenging and uncomfortable, this is important, productive work. In Camara Phyllis Jones’ words,

Answering ‘how is racism operating here?’ can be a powerful approach to identifying levers for intervention.9

Our faculty asked for a committed and visible effort to take the department as a whole down this path that some faculty had been suggesting for a long time. This story picks up with that first large-scale faculty meeting, which took place in October 2019 before either COVID-19 or the killing of George Floyd.

This was designed as a developmental path for the department and for its many individuals—a wide-ranging task, not a narrow, technical, or quick fix. This meant taking all faculty on a participatory journey to bring changes in everything they do, therefore building an inclusive means to an inclusive end.

Sixty-five faculty (with administrative leaders) met for 3 hours face to face to shape an intellectual framework and action agenda, captured so people could be quickly released on those tasks. The meeting was authored by a design team of faculty (including authors M.A. and A.W.) and University EDI consultants with facilitation by a faculty (author C.J.P.) and department administrator (author W.N.); and guided by the department head (author J.T.P.). Attendees worked in urban and outstate residency programs, other clinical programs, medical student education, and research—a department cross-section.

The meeting plan accepted that faculty have a wide range of awareness, experience, interest, and skills in areas of EDI. It was designed for all, engaging everyone at whatever level of readiness and whatever aspects in which they are most interested. This was served by recognition of three pillars of EDI action in a family medicine department:

- Care delivery and health,

- Workforce recruitment and retention, and

- Learner recruitment and training.

Though differentiated here, these are highly related. Diversity in learners brings a diverse workforce and ultimately a diverse health care team for the care of all patients and achievement of health equity. Equity in research cuts across all three.

The distribution of strongest faculty interest in these pillars was found to be almost evenly in thirds, depending on their roles, history, and personal commitments. Leaders quickly realized that everyone’s most authentic interests and energy would have to be accommodated and harnessed from the very beginning, leaving no one feeling excluded, minimized, or waiting for their turn. All would need to take the journey together, regardless of driving interests or level of comfort and confidence.

1. A Shared Intellectual Framework—Definitions and Goals Across the Three Pillars

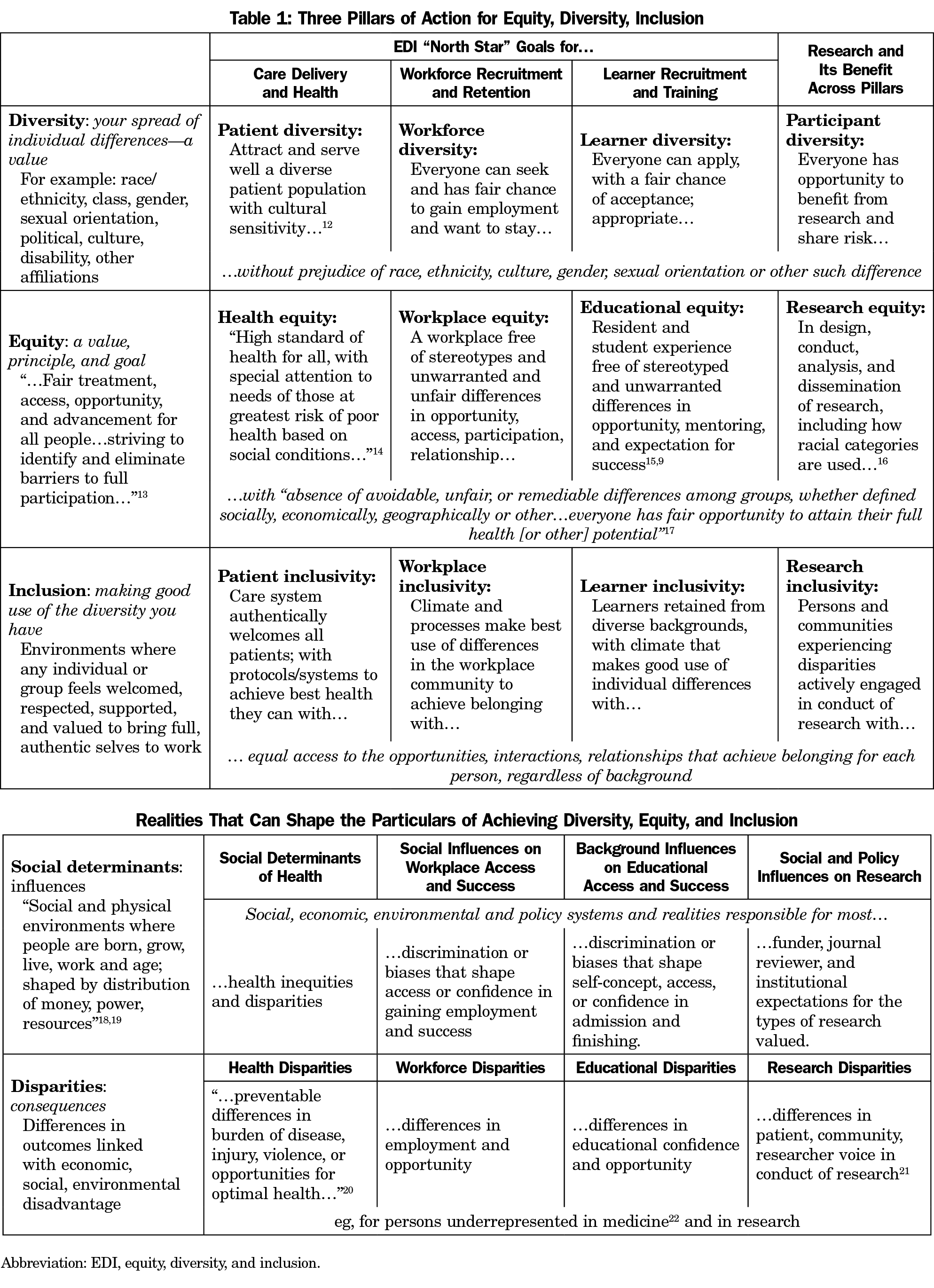

One way to address anxious feelings about not knowing enough, being misunderstood, saying the wrong thing, or being overwhelmed by complexity was to create a shared intellectual framework for navigating the work as part of the opening conversation. For example, people may not share meanings of basic EDI terms. Definitions pages helped the conversations proceed rather than bog down in confusion at tables. But beyond definitions, this intellectual framework showed how equity, diversity, and inclusion play out in the three pillars of work in a family medicine department. Table 1 shows EDI definitions with translations for each pillar and a high-level goal or “north star” to seek in each. It also shows north star goals for making research more equitable, something that crosses all the pillars. The developmental path involves taking action in all those cells.

2. Shared Acceptance of Uncomfortable Local Reality and Need for Change

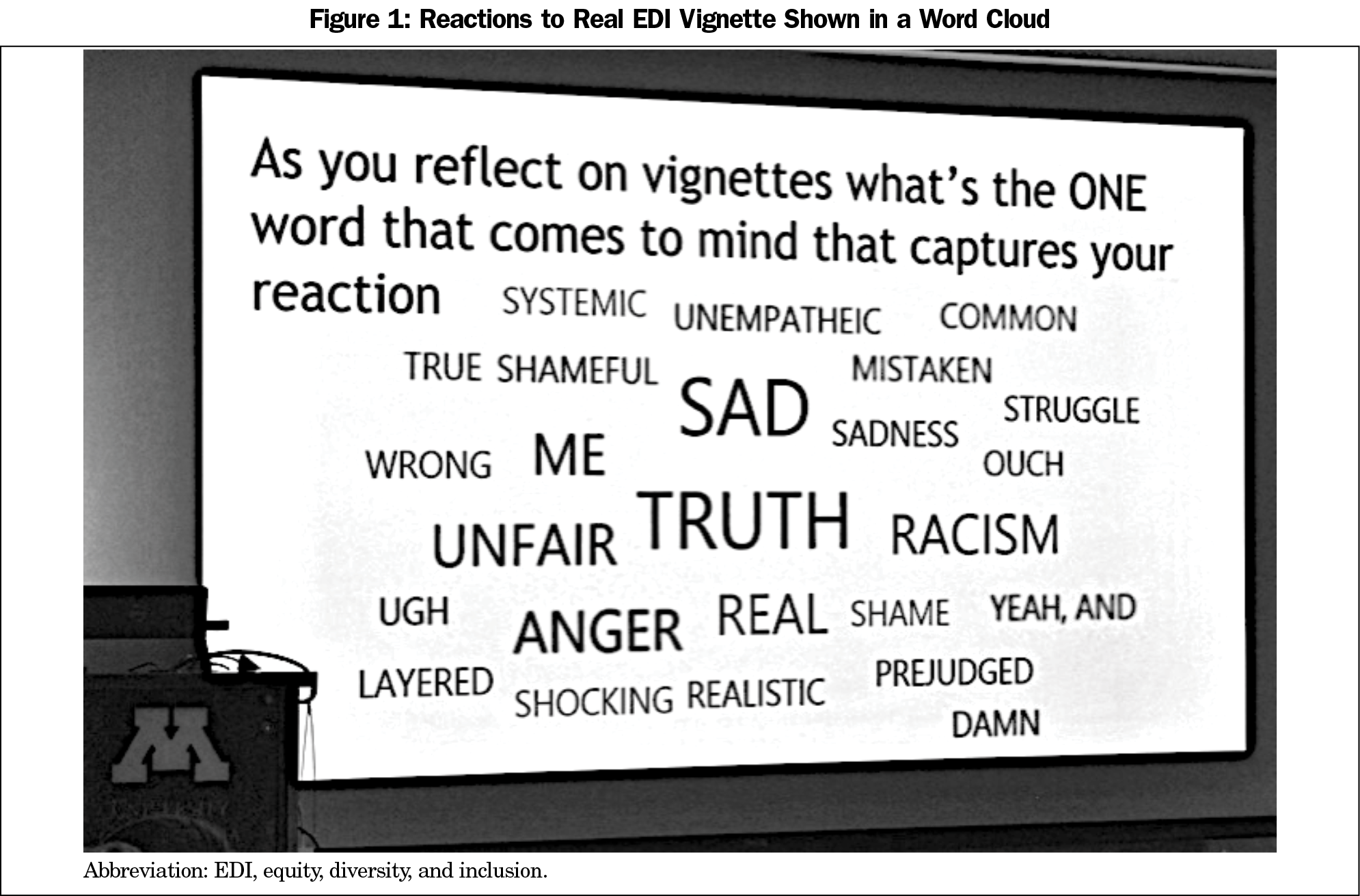

A vignette created from stories told by residents in our own system illustrated personal experiences of systemic racism such as everyday insults, indignities and demeaning messages (microaggressions).23 The vignette, read aloud, portrayed (1) different staff assumptions about causes, treatments, results, desires, or appropriate communication for non-English-speaking patients or patients of color; and (2) different treatment of residents and physicians of color (eg, being mistaken for interpreters, not having orders taken as seriously, or people talking down or being less helpful educationally).

The assembled group was moved by the vignette. Immediately afterward, a live clicker poll asked people for the one word that came to mind while listening to the vignettes (Figure 1).

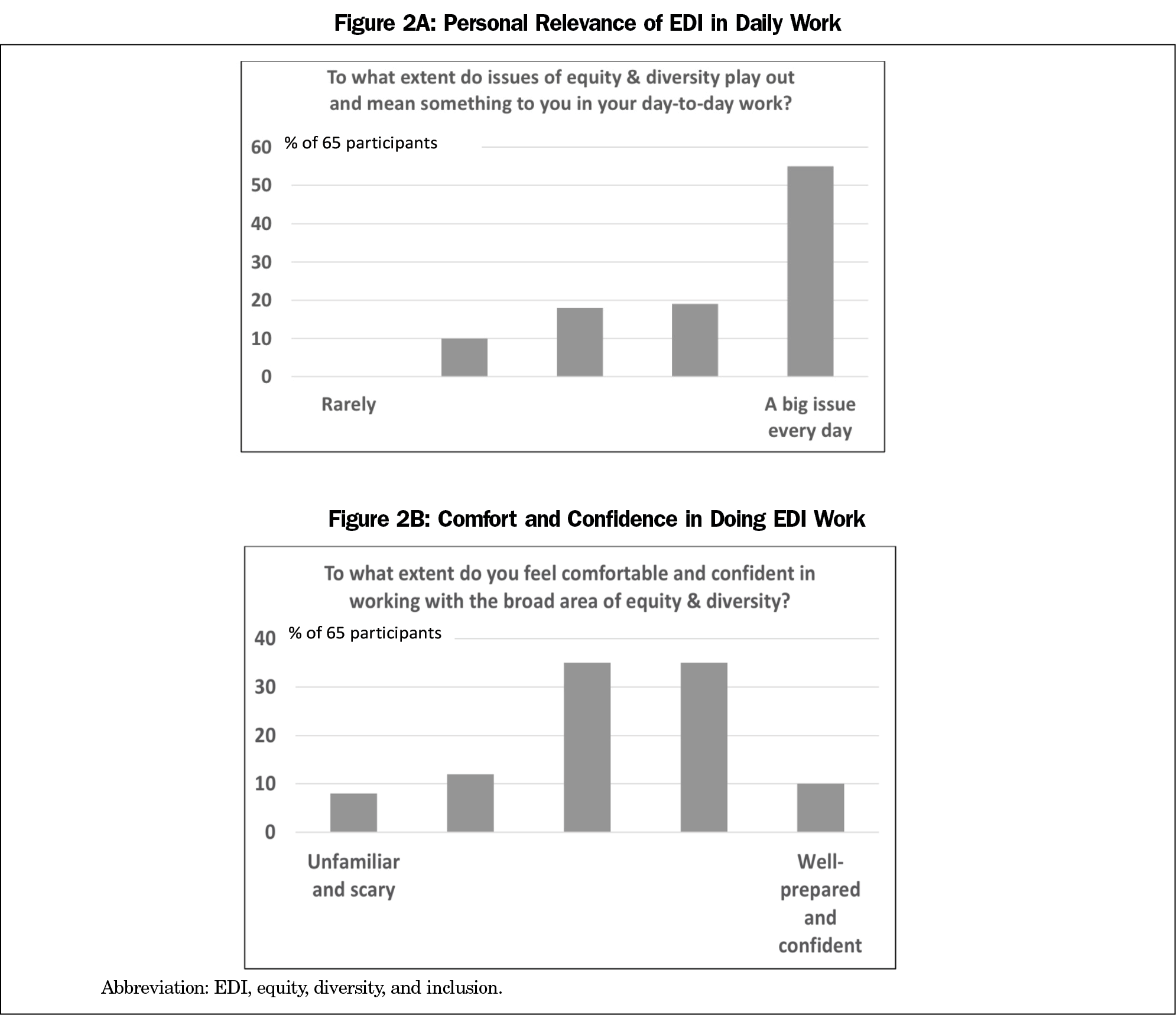

Then a clicker poll asked for the relevance of EDI in daily work, along with individual comfort, confidence in addressing EDI (Figures 2A, 2B). This showed EDI as a big issue in daily work and a wide range of comfort and confidence with addressing it. People were relieved to see this all this out in plain view, grounded in local reality, as they moved into table work to identify the department’s top growth areas and actions to take.

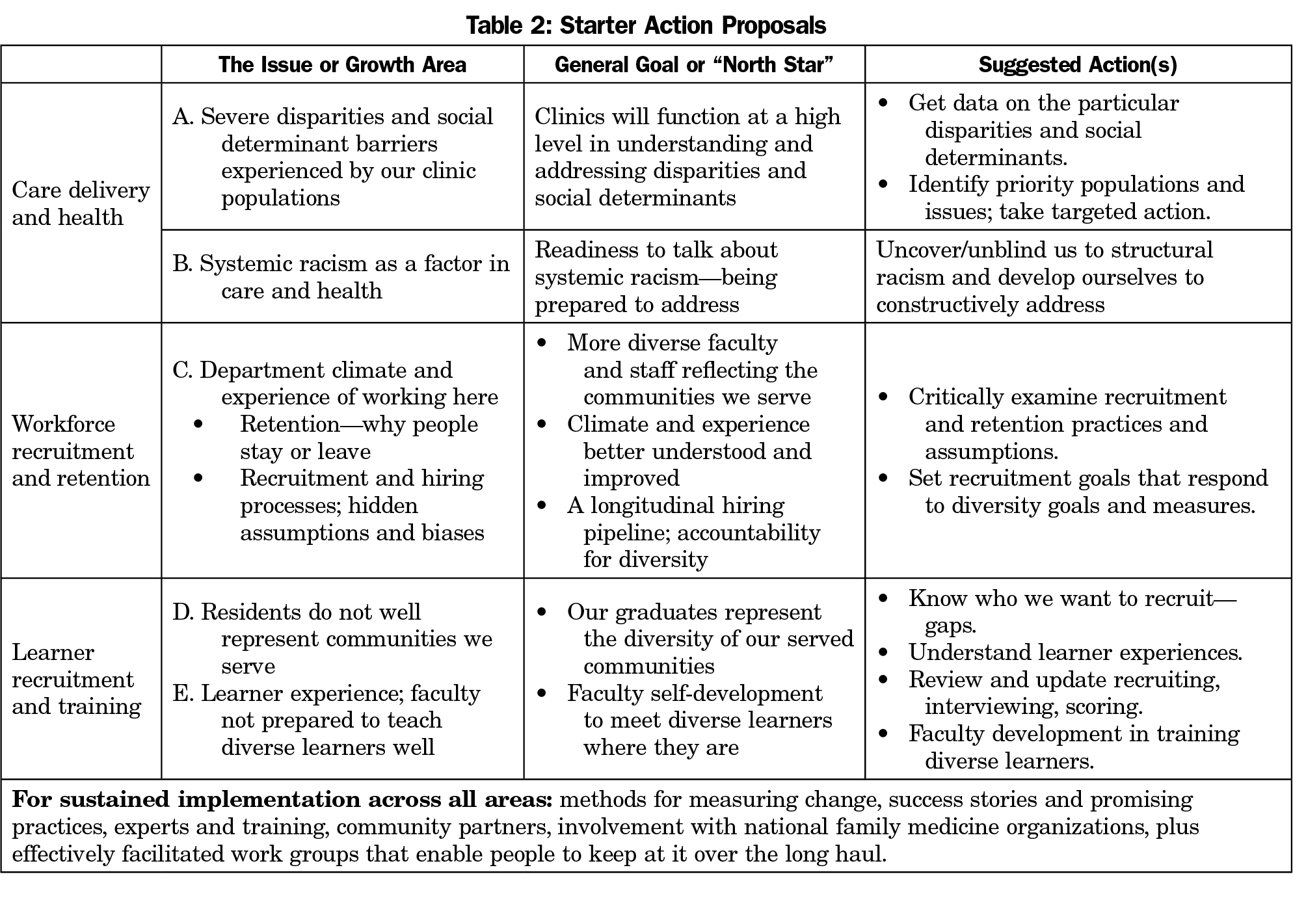

3. A Department Self-assessment—Top Growth Areas With Actions to Take

Faculty at tables, seated by heartfelt interest area (one of the three pillars), identified top growth areas and action plans—the shared work to achieve equity embedded in everything we do (Table 2).

4. Harnessing the Energy for Action—Many Volunteers, a Visible Leader, a Charge, a Process

Power to change would lie in releasing the many people passionate about the work in the different pillars rather than just picking one or two things or a handful of people to work on behalf of everyone else. At least 21 faculty volunteers from 10 different department programs signed up at the opening meeting for subsequent group work to carry out action plans.

Afterward, the department head established an EDI vice chair with a charge to take people down a path that embodies EDI as a way of operating in everything we do. This leader is a member of and accountable to the department executive team, the central source of departmental power, resources, commitment and ultimate decision-making. This role bridges and aligns department levels and people, discovering where power to change exists and how to use it (eg, making decisions locally, setting direction centrally, exerting social influence, facilitating and organizing), and leveraging the larger medical school and university institutions. This is a broad-based work effort across all interested faculty, staff, and learners and did not place the work and responsibility on minority faculty and residents. We are attempting to avoid or reduce such a “minority tax”24 for carrying the burden of educating colleagues and leading diversity efforts.25 Specific actions include providing financial incentive for justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (JEDI) work across all department faculty, engaging EDI leadership at the medical school, university, and practice organization levels, and engaging the help of outside consultants for faculty development and education.

At early stages, action began by employing the visible leadership and broad engagement with the original action areas, but with reference to a top-line vision: “More equitable and just health care and education in a more equitable and just society.”

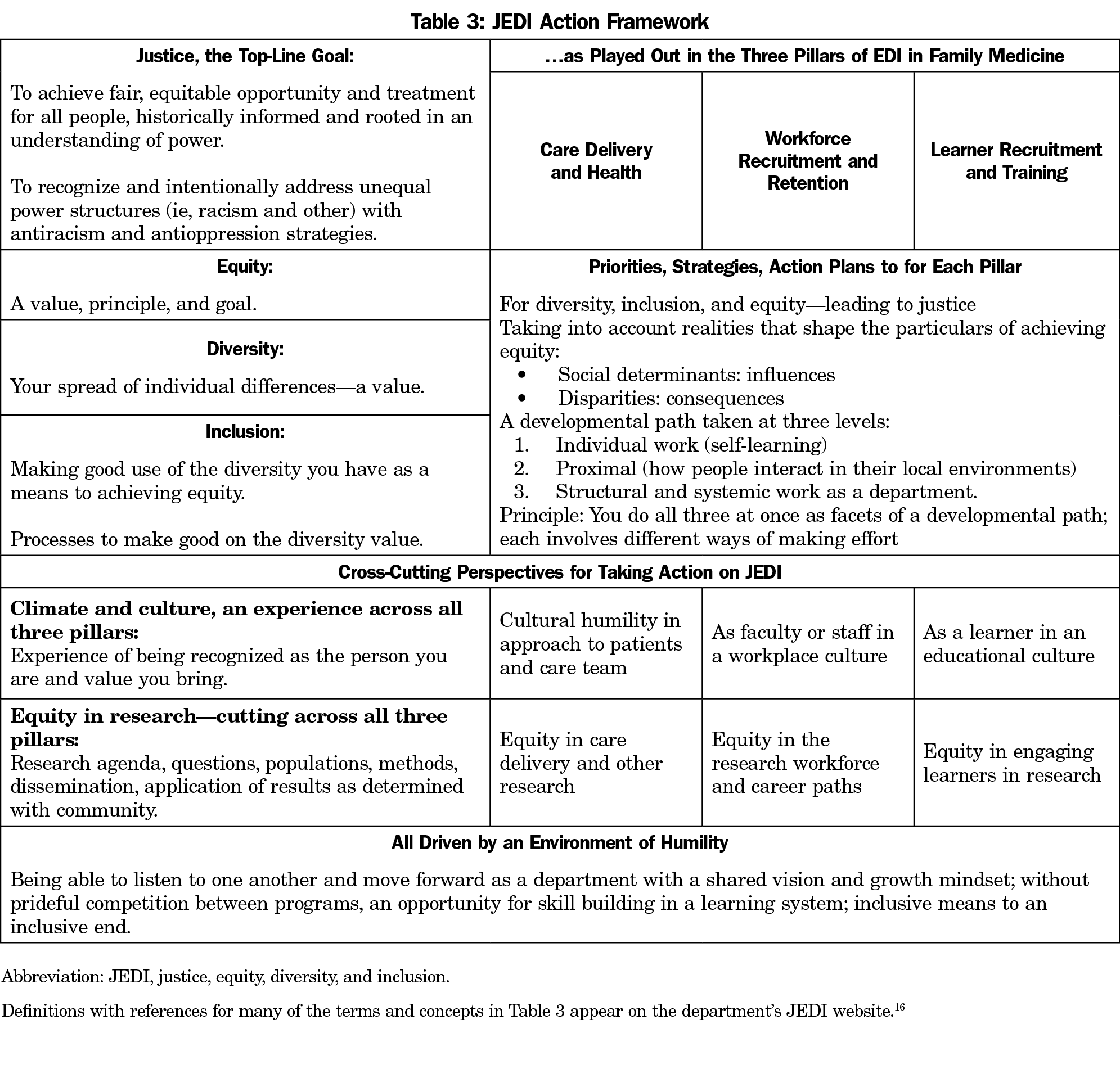

In this vision, justice as an overarching goal flows from equity—with diversity and inclusion (via climate and culture) as the means. Hence the acronym for the department path evolved from EDI to JEDI.** The Vice Chair for JEDI, Andrea Westby, MD) leads a broad group of faculty, residents, and staff from across the many department programs, divided into subgroups working from a JEDI action framework (Table 3) that acknowledges actions that cross all three pillars:

- Acknowledge and work to eliminate racism in all its forms—structural, institutional, systemic, interpersonal, and internalized. Identify and change systems, structures, policies, processes, and attitudes in care delivery, medical education, research, and our workplace that contribute to racism as a public health crisis.26

- Assess and improve climate and culture—the experience of working, learning, and receiving care in all departmental spaces to make them welcoming, inclusive, and safe. Recognize that different social categories (eg, race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status) intersect to create unique experiences for individuals that should all be valued.9

- Improve equity in research—consider equity in questions, populations, samples, methods, analysis, and application of results—all with real community participation in these choices. Do justice to diverse populations and their concerns in a way that rebuilds trust in the research enterprise.27,16 Promote the value of such research in the institution, journals, and career paths.

The department is early on its path, with most structures, policies, and processes yet to measure or show sustained improvement. We report this now, rather than waiting to report mature outcomes later, to illustrate the kinds of work and thinking that quickly emerged in response to department and institutional commitment to address these issues and to invite conversation with other departments.

1. Becoming Centered on How Change Occurs—Principles of Emergence

JEDI participants began to see change emerging from relationships and dialogue between people doing the work—taking advantage of situations, opportunities, and chance happenings all around them. An emergence framework has helped people normalize this experience and make good use of it:

Principles of emergence [are] the way complex systems and patterns arise out of relatively simple interactions.28

Emergent strategy [is] plans of action, personal practices, and collective organizing that account for constant change and rely on the strength of relationship for adaptation.29

An umbrella motto is “practice the future together,” accompanied by a set of principles or aphorisms that have become reminders for how to be effective.***

2. Climate and Culture

A starting point is changing patterns in where and how individuals can be heard. We have inherited a hierarchically structured organization, not a flat one. How can we simulate a flatter structure where everyone can more easily be heard? For example, our JEDI group has created an environment where every concern and voice has weight. This is a decision within our own circle of influence; we can at least flatten our own work. This happens by action in relationship and with intentional and public modeling of what we want to see. This also exemplifies another principle of emergence, that of fractals, where what we are in the smallest interaction is what we embody as a larger organization.

3. Bring an Equity Lens to the Conduct of Departmental Relationships

Meeting with clinical partners, affiliates, learners, faculty, staff, and EDI leaders helped reveal obstacles to equity on the ground, making it easier to reinforce one another in doing the right things and to see more clearly what people need (eg, frameworks, education, processes). A specific example is family medicine-led collaboration with Departments of Medicine and Ob-Gyn on faculty development curricula.

Another example is embedding community-driven initiatives and perspective into all department and clinical committees using an “equity-empowered” lens.30 Community engagement processes on the clinical side were adapted from advanced community engagement being done on the research side by our program in health disparities research, leaders and experts in community-based participatory research (CBPR) where community engagement is a transferrable core competency.31

4. Model a Constructive Approach to Specific EDI Incidents

Incidents occur, for example, in behavior toward someone in clinic, social media posts, or overt discrimination. When situations arise, the traditional private human resources-centered approach can be complemented with a learning organizational mindset that includes an opportunity for learning and individual growth, systemic improvement in addressing harms for affected individuals and groups and how wider systems can be changed to prevent reoccurrence. In the words of the Hope Commission to lead health equity efforts of our larger clinical health system:

It’s important for all of us to recognize and expect that we will not get everything right the first time as individuals or as organizations. We need to give ourselves and each other room to make mistakes and learn from them, and do things better the next time. In this way, we will develop and strengthen our knowledge, skills, and capability over time, both individually and as an enterprise.32

5. Provide JEDI Tools and Education

A department toolkit introduced for 2021 learner recruitment includes an exercise that connects JEDI goals and evidence (a JEDI lens) to recruitment processes, along with a medical school training called “Implicit Bias in the Search and Selection Process” for residency and postdoctoral fellow program leaders. Workshops, such as “Responding to Harassment and Bias in the Clinical Learning Environment” are available. Other resources for faculty, staff, and learner self-education and curricula are on a new website for easy access.26 A “JEDI Elective” enables residents to receive time and educational credit for their participation in JEDI workgroups and projects. A structured longitudinal educational curriculum is in process, along with exploration of a faculty development fellowship for people from backgrounds historically marginalized in medicine.

6. Policy Review Using an Equity Lens

Examples include a community-friendly institutional review board wording for HIPAA statements, clinic policies around late patients, policies on scheduling meetings for people with small children and in places without elevators. Evaluation is taking place on the ways that faculty candidates are identified, recruited, and retained, with interventions at each of those levels. Policies are being examined on what is valued for purposes of promotion and tenure, especially the value placed on work related to disadvantaged communities or other areas of heartfelt interest to minority faculty. Eligibility rules are being examined for loan repayment in academic settings where the job includes not only clinical hours, but also a broad portfolio of work.

7. JEDI Evaluation and Measurement

Metrics for evaluating JEDI progress are being developed. These include a mix of equity outcomes and equity processes, both qualitative and quantitative, with a mix of metrics used by the medical school office for diversity, equity, and inclusion, and those devised for our particular situation. Improvements in how demographic data are collected in the clinical setting will better track disparities via quality metrics stratified by race, ethnicity, language, and insurance status. Because our clinical programs work within several different care systems, they will need to ask for those reports in the particular data languages used by those systems.

Invitation to Further Conversation Among Departments

Though complex and sensitive in different ways for different people, EDI work in a large academic department can proceed with a shared intellectual framework and inclusive engagement processes that take the department down its own developmental path. The path is long and challenging, with only a beginning described here. It will take the sustained effort of many department members to make second nature the deep change that leads to equity in care delivery and health, the workplace, and learner training, while also attending to the cross-cutting dimensions of racism, climate and experience, and equity in research.

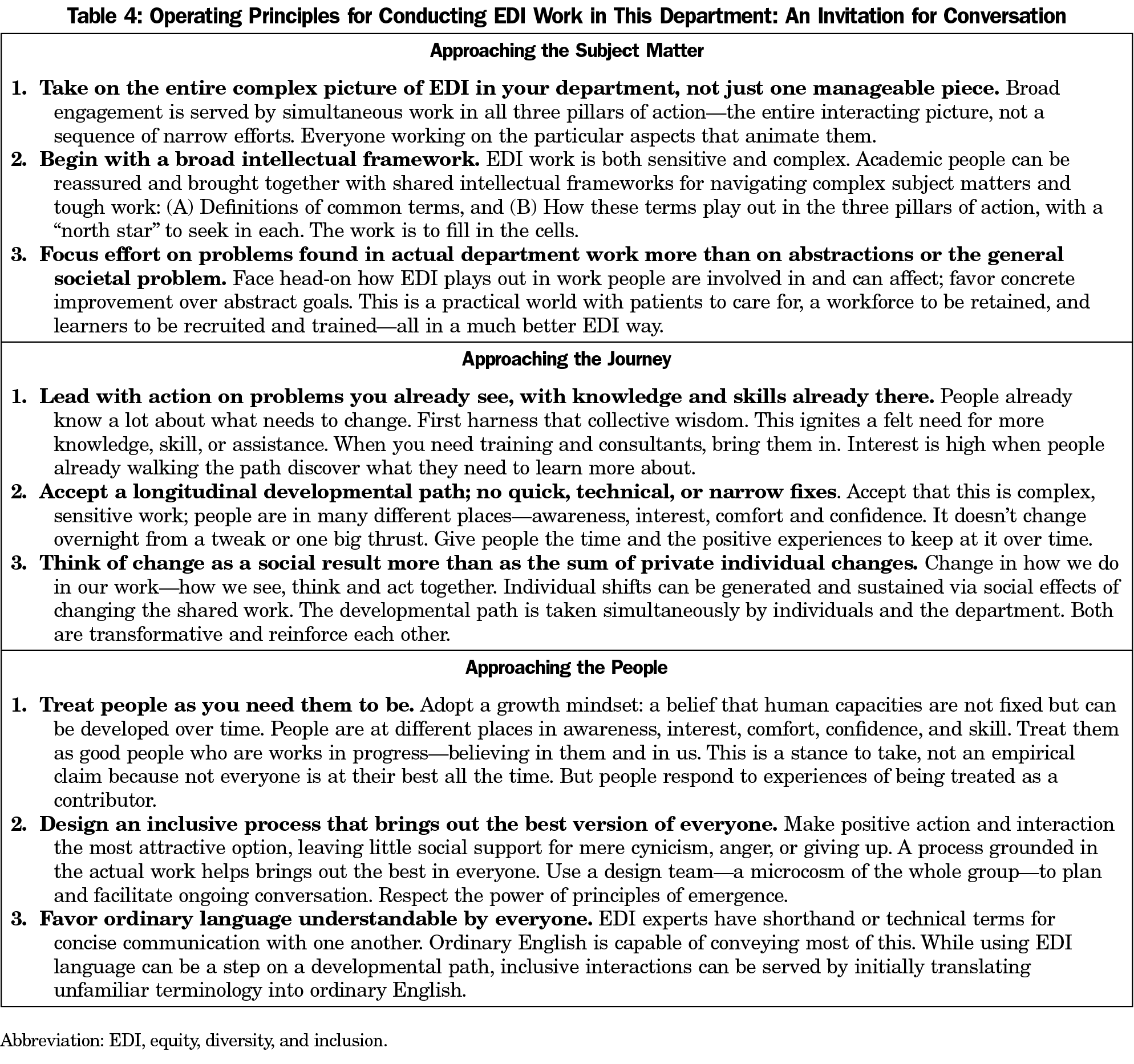

While each department has its own situation and priorities, they all face the question of how to conduct their own process to improve EDI—a choice of operating principles to increase the chance of success. Though our journey is far from complete, we offer for conversation among departments a set of operating principles from which we are now working (Table 4). These are not recommendations. They are only a reconstruction of how we have been going about this work. Our journey will be more successful by engaging our larger institution and our colleagues across the country. We hope this article stimulates conversation about beginning and proceeding constructively with EDI change in family medicine departments.

* Different departments and institutions use different arrangements of the letters E, D, and I in their acronyms. The decision was made to use EDI, leading with the overarching goal, E for equity, followed by D for diversity as part of the means, and I for inclusion as a way to get the most from diversity—a logical progression.

** JEDI: A figure in the Star Wars films, trained to guard peace and justice.

*** Examples of principles of emergent strategy: small is good, small is all (the large is a reflection of the small, as in “fractal”); change is constant; there is a conversation in the room that only these people can have—find it; never a failure, always a lesson; trust the people (if you trust the people, they will become trustworthy); move at the speed of trust; focus on critical connections more than critical mass—build resilience by building relationships; less prep, more presence; what you pay attention to grows.

Acknowledgments

To create “inclusive means to inclusive ends” for faculty at very different places with very different interests, the authors thank the process design team for their work:

Brooke Cunningham, MD, PhD, and Josh Thompson, MD (UMN Family Medicine Department faculty); Stef Jarvi (Director of Education in UMN Office of Equity and Diversity), Keisha Varma, PhD (Associate Vice Provost, UMN Office for Equity and Diversity), and Christina Steere (Human Resources Director, UMN Department of Family Medicine and Community Health).

Previous Presentation: A test version of the intellectual framework of Table 1 was used in breakouts in February 2020 and February 2021 at the Association of Departments of Family Medicine (ADFM) to test for clarity and usefulness.

References

- Johnson M, Douglas M, Grumbach K, et al. Advancing diversity, inclusion and health equity to the next level. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(1):89. doi:10.1370/afm.2348. Accessed May 15, 2021.

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Statement on Dismantling Racism in Academic Medicine. February 23, 2021. Accessed May15, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/aamc-statement-dismantling-racism-academic-medicine.

- COVID-19 Health Equity Considerations and Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. July 24, 2020. Accessed May 15, 2021. cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html

- Millett GA, Jones AT, Benkeser D, et al. Assessing differential impacts of COVID-19 on black communities. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;47:37-44. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.05.003

- Galea S, Abdalla SM. COVID-19 Pandemic, Unemployment, and Civil Unrest: Underlying Deep Racial and Socioeconomic Divides. JAMA. 2020;324(3):227-228. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.11132

- Evans MK. Health Equity—are we finally on the edge of a new frontier? September 10, 2020. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(11):997-999. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2005944

- Hardeman RR, Medina EM, Kozhimannil KB. Structural Racism and Supporting Black Lives - The Role of Health Professionals. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2113-2115. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1609535

- Jones CP. Toward the Science and Practice of Anti-Racism: Launching a National Campaign Against Racism. Ethn Dis. 2018;28(suppl 1):231-234. doi:10.18865/ed.28.S1.231.

- Hardeman RR, Burgess D, Murphy K, et al. Developing a medical school curriculum on racism: multidisciplinary, multiracial conversations informed by Public Health Critical Race Praxis (PHCRP). Ethn Dis. 2018;28(suppl 1):271-278. doi:10.18865/ed.28.S1.271.

- Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota Medical School. Accessed May 15, 2021. https://med.umn.edu/familymedicine

- Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991;43(6):1241-1299. doi:10.2307/1229039

- Cultural Sensitivity. American Academy of Family Physicians. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/cultural-proficiency-position-paper.html

- The Just Imperative. MacArthur Foundation. Accessed May 22, 2021. https://www.macfound.org/about/how-we-work/just-imperative

- Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(1_suppl2)(suppl 2):19-31doi:10.1177/00333549141291S206

- Osseo-Asare A, Balasuriya L, Huot SJ, et al. Minority resident physicians’ views on the role of race/ethnicity in their training experiences in the workplace. JAMA Netw Open.2018;1(5):e182723. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2723

- Durant RD, Legedza AT, Marcantonio ER, Freeman MB, Landon BE. Different types of distrust in clinical research among Whites and African Americans. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2011; 103 (2):123-130. doi:10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30261-3

- Equity. World Health Organization. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/equity/en/

- Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/understanding/sdh-definition/en/

- Healthy People 2020: Understanding and Improving Health. US Dept. of Health and Human Services. Accessed May 21,2021. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health

- Health Disparities. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/disparities/index.htm

- Edmunds M, Bezold C, Fluwood CC, Johnson B, Tetteh H. Diversity and inclusion in health services research workforce. Washington, DC: Academy Health. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.academyhealth.org/sites/default/files/AH_230DiversityReport%202015_09.15.pdf

- Underrepresented in Medicine Definition. American Association of Medical Colleges. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/diversity-inclusion/underrepresented-in-medicine

- DeAngelis T. Unmasking ‘racial microagressions’. American Psychological Association Monitor on Psychology. 2009;40(2). Accessed May 15, 2021. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2009/02/microaggression

- Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):6. doi:10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9

- Foster KE, Johnson CN, Carvajal DN, et al. Dear White people. Ann Fam Med. 2021;19(1):66-69. doi:10.1370/afm.2634

- JEDI Framework. University of Minnesota Department of Family Medicine Equity, Diversity & Inclusion. Accessed May 20, 2021. https://med.umn.edu/familymedicine/equity-diversity-inclusion/jedi

- Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, Hoffsuemmer J, Martin E, Edwards D. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):879-897. doi:10.1353/hpu.0.0323

- Obolensky N. Complex Adaptive Leadership: Embracing Paradox and Uncertainty. Burlington, VT: Gower; 2014.

- Brown AM. Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds. Chico, CA: AK Press; 2017.

- From Savior-Designed to Equity-Empowered Systems. National Institute for Children’s Health Quality. Accessed May 15, 2021. https://www.nichq.org/insight/savior-designed-equity-empowered-systems

- Resources for Community-engaged Research. University of Minnesota Program in Health Disparities Research. Accessed May 15, 2021. https://med.umn.edu/healthdisparities/community-engagement/resources.

- HOPE Commission Vision and Approach. MHealth Fairview Hope Commission. Accessed May 15, 2021. https://mhealthfairview.org/-/media/MHealthFairview/Project/MHealthFairviewOrg/PDFs/HOPE-Commission/8650-HOPE-Commission_Document-3.ashx