Background and Objectives: Recent evidence has suggested that fewer family medicine clerkships are using community preceptors as their primary source of teaching. One way to incentivize community preceptors is to pay them. Multiple factors, though, make payment of community preceptors complex. Our study looked at trends in payment of community preceptors in the United States and Canada over the past decade.

Methods: We performed a secondary analysis of the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance annual family medicine clerkship director surveys from 2014 to 2023. We analyzed the surveys’ standard clerkship payment questions and identified trends using Pearson’s correlation coefficient test.

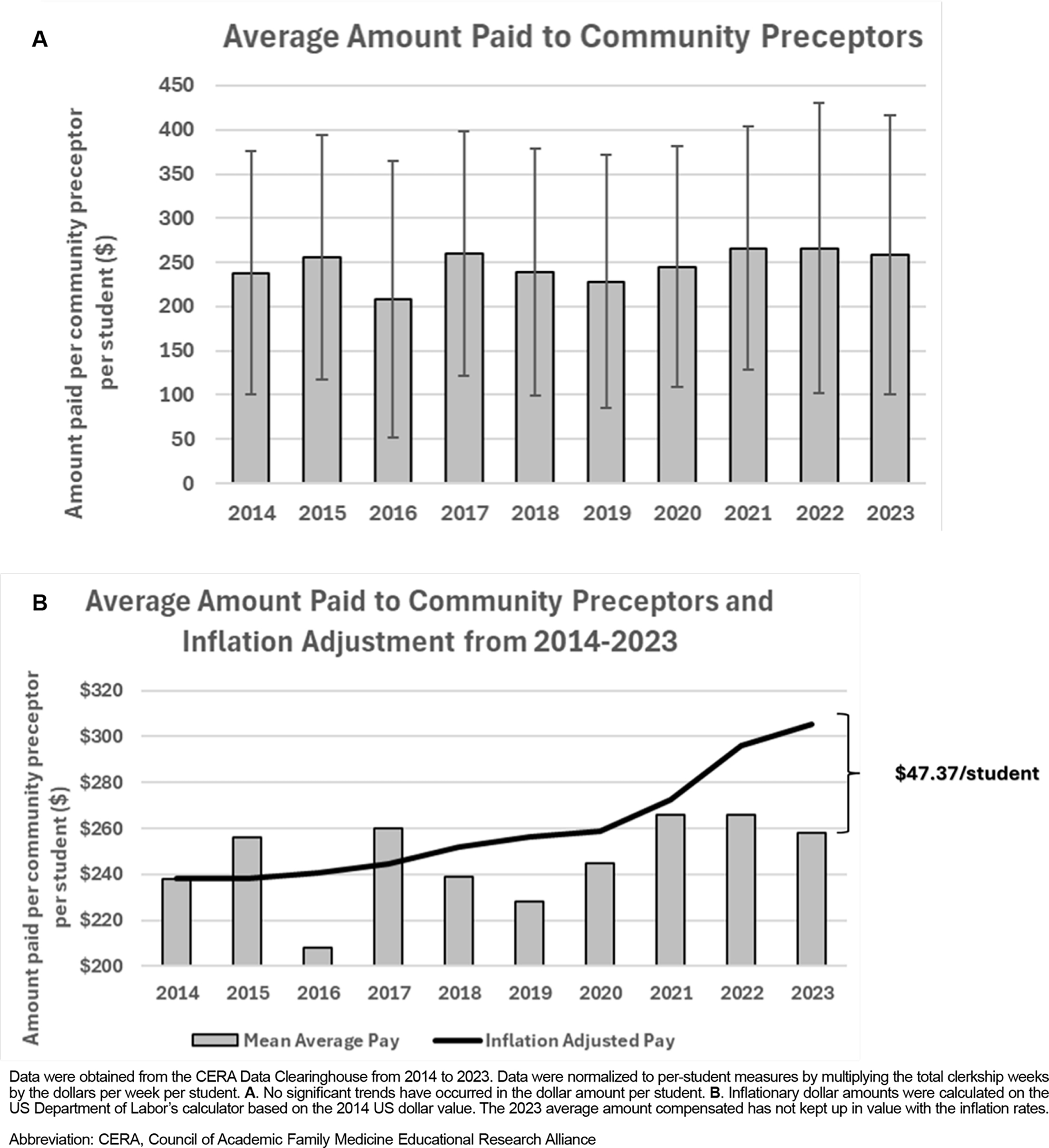

Results: From 2014 to 2023, we found no significant change in the number of medical schools that pay community preceptors in the family medicine clerkship. We also found no significant change in the amount paid to community preceptors in the family medicine clerkship. In 2014, the average amount paid was $238±138 per student, compared to 2023 where the average amount paid was $258±$158. When analyzed against inflation, these data reflect that a significant gap in the value of the compensation for community preceptors has developed.

Conclusions: The compensation of community preceptors in US and Canadian family medicine clerkships has not kept up with inflation. Additional research is needed to study the motivations of community preceptors to educate in the family medicine clerkship and how both monetary and nonmonetary incentives can help recruit and retain these important educators.

Experience in primary care is a core requirement of the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, the Committee on Accreditation of Canadian Medical Schools, and the Commission on Osteopathic College Accreditation.1,2,3 The family medicine clerkship most commonly satisfies this requirement. Family medicine clerkship preceptors include both medical school-employed physicians and community physicians who agree to teach and mentor medical students.

Many medical schools rely heavily on community preceptors for family medicine clerkship teaching; since 2020, however, the use of community preceptors has declined.4,5 Community preceptors who volunteer to teach medical students are committed to educating future physicians, often without compensation.6 Increasing emphasis on clinical productivity may have contributed to the decreased engagement of community preceptors in recent years, prompting some medical schools to consider offering them financial incentives.7,8

In 2014, Anthony et al reported that few medical schools compensated their family medicine community preceptors, with a higher likelihood of compensation in the Southeastern region of the United States.6 By 2019, Christner et al. noted an increase in the number of medical schools paying community preceptors across multiple specialties, again predominantly in the Southeastern United States.9 A factor analysis by Johnston et al in 2022 showed that paying community preceptors was an important external motivator to incentivize them.10

This study aimed to describe recent trends in the payment of community preceptors for family medicine clerkships. Understanding these trends can inform US and Canadian clerkship directors and medical schools how to effectively compensate family medicine clerkship preceptors. Recruiting more community family physicians as preceptors also may encourage more medical students to pursue family medicine.11,12

Data were obtained from the publicly available CERA Data Clearinghouse.13,14 The Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) conducts annual cross-sectional surveys of allopathic and osteopathic family medicine clerkship directors from the United States and Canada.15 These surveys begin with standardized questions regarding characteristics of the family medicine clerkship they oversee. In these surveys, all family medicine clerkship directors receive an email invitation to participate, followed by two email reminders before the survey closes. CERA surveys remain open for 1 month prior to being closed by administrative personnel. The data are made publicly available 90 days following the closing of each survey on the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine website. We obtained data from each CERA clerkship director survey from 2014 to 2023,, which we downloaded into Microsoft Excel (version 2504).

We extracted clerkship payment data from each survey from 2014 to 2023 for trendline analysis.16 In past surveys, questions were worded to elicit payment per student; more recent surveys have changed this question to elicit payment per week per student. To rectify this discrepancy, we multiplied the payment per week by the number of clerkship weeks to get a per student value. We chose to use the per student value because this value was what previously published data reported.6 We analyzed questions regarding the percentage of community preceptors that are paid, amount paid per student, medical school type, and medical school region. We used descriptive statistics to describe trends in the data. We calculated inflationary changes using the Bureau of Labor Statistics calculator with the reference date of September 1, 2014 (the date the 2014 clerkship director survey opened for responses).17 Data were analyzed using R statistics software version 4.2.2 (R Foundation). Trendline analysis was performed using linear logistic regression and Pearson’s correlation coefficient test.

These surveys were approved by the American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board prior to initial administration.

We analyzed family medicine clerkship director CERA surveys from 2014 to 2023. Individual survey response rates ranged from 48.8% in 2021(78/160) to 85.8% in 2016 (121/141). Longitudinal descriptions of clerkship director demographics18 and family medicine clerkship characteristics4 from these surveys have been previously published.

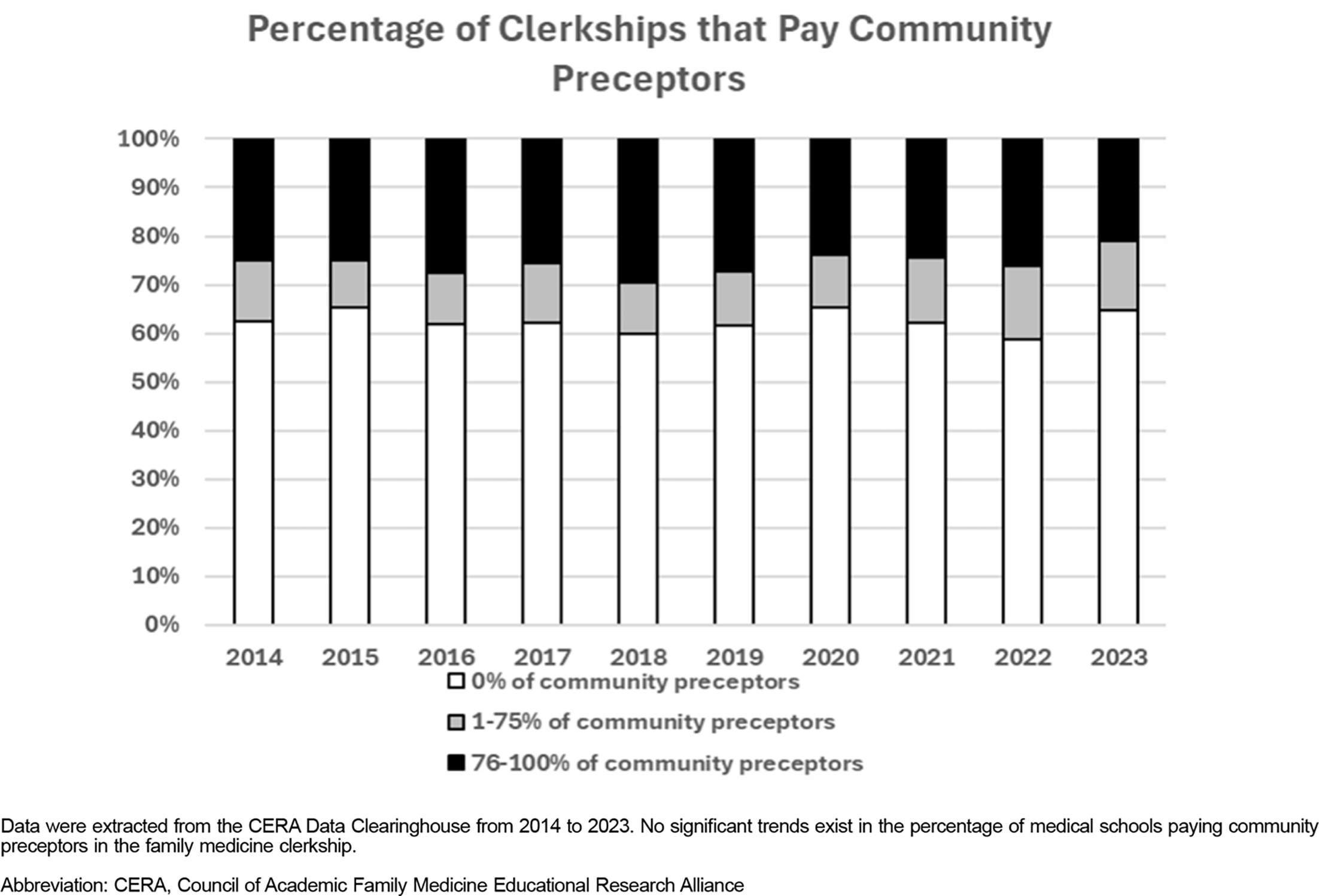

We found no significant change in the percentage of family medicine clerkships that pay their community preceptors to participate in the family medicine clerkship (Figure 1). The percentage of clerkships that paid community preceptors in 2014 was 33.3% (45/135), and in 2023 it was 35.2% (32/91). Of the clerkships that paid community preceptors, a majority paid 76%–100% of their community preceptors (59.4% [19/32] to 73.7% [28/38] with year-to-year variability based on responding clerkship directors and no statistically significant trend), and a minority paid 1%–75% of their community preceptors (26.3% [10/38] to 40.6% [13/32]).

We analyzed the average amount paid to community preceptors. We found no significant change in the average amount paid per student since 2014 (Figure 2A). In 2014, the average amount paid was $238±138; in 2023, the average amount paid was $258±158. We found significant year-to-year variability based on clerkship directors’ responses but found no statistically significant trend. We used the 2014 average amount paid to determine the relative inflationary value over time (Figure 2B). With inflation considered, the 2014 average amount paid would be equivalent to $305.37, a difference of $47.37 per student.

Our findings demonstrated that although monetary compensation for community preceptors to teach in the family medicine clerkship is an important external motivator,7,10 no changes have taken place in the percentage of medical schools paying community preceptors nor in the average amount paid. Despite no change in community preceptor payment, compounded with the increasing numbers of US medical students, the demand for community preceptors continues to grow.19 Beyond the number of new medical students, the difficulties in recruitment of community preceptors has been exacerbated by productivity demands, documentation burdens, and competition from nonphysician trainees.9 These challenges necessitate innovative strategies to ensure that medical students have sufficient access to community sites.20

Although some schools compensate their community preceptors, the monetary amount has not changed over the past decade. When adjusted for inflation, the real value of this incentive has declined to about 85% of the 2014 real-world value. Possible causes of stagnant compensation over the past decade include institutional budget constraints and a lack of national policy support for community care training sites.21

Our study should be interpreted with the following limitations. The CERA data from 2014 to 2023 included variability in response rates from year to year and did not track which institutions completed the survey each time. Inability to track specific institutions from year to year would hide clerkships that newly compensated community preceptors, stopped paying community preceptors, or made changes to the compensation of community preceptors. Additionally, these data solely pertained to family medicine clerkship experiences and does not account for other interactions with family medicine community preceptors such as preclinical experiences. Furthermore, the data collected considered only monetary compensation and excluded other nonmonetary benefits provided by adjunct faculty status.

Given that most medical schools do not offer monetary compensation to their community preceptors, future research exploring alternative nonmonetary incentives to recruit and retain these vital educators may be important. In addition, understanding whether and how other specialties compensate community-based education can further inform future medical school administrative processes and policy work.

References

-

-

-

-

Ringwald BA, Banas D, Macerollo A, Bruce E, Farrell M. Evolution of the family medicine clerkship: a CERA secondary analysis.

Fam Med. 2025;57(6):410–416. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2025.306815

-

Rutter A, Theobald M. Committee tackles community preceptor shortage.

Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):484–486. doi:10.1370/afm.2129

-

-

Minor S, Huffman M, Lewis PR, Kost A, Prunuske J. Community Preceptor Perspectives on Recruitment and Retention: The CoPPRR Study.

Fam Med. 2019;51(5):389–398. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.937544

-

Hatfield J, Neal G, Isbell T, Dickey D. The effect of a medical student on community preceptor productivity.

Med Educ. 2022;56(7):747–753. doi:10.1111/medu.14733

-

Christner JG, Beck Dallaghan G, Briscoe G, et al. To pay or not to pay community preceptors? that is a question ….

Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(3):279–287. doi:10.1080/10401334.2018.1528156

-

Johnston A, Malhi R, Cofie N, et al. Currencies of recognition: What rewards and recognition do Canadian distributed medical education preceptors value?

MedEdPublish (2016). 2022;12. doi:10.12688/mep.17540.1

-

Alavi M, Ho T, Stisher C, et al. Factors that influence student choice in family medicine.

Fam Med. 2019;51(2):143–148. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.927833

-

Lee AL, Erlich DR, Wendling AL, et al. the relationship between medical school clerkships and primary care specialty choice: a narrative review.

Fam Med. 2022;54(7):564–571. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2022.857719

-

-

Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW. Creating a centralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research.

Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257–260. doi:10.1370/afm.2228

-

-

-

-

Ringwald BA, Edwards Y, Vengal S, Montemayor J, Ringwald C. The changing faces of academic family medicine leadership: A CERA secondary analysis.

Fam Med. 2025;57(3):201–207. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2025.804452

-

-

Theobald M, Everard KM, Morley CP. Changes in the shortage and quality of family medicine clinical training sites.

PRiMER. 2022;6. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2022.960678

-

There are no comments for this article.