CERA, the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance, aims to provide a collaborative and cohesive research network for family medicine scholars that engages residency directors, clerkship directors, department chairs, and the general Council of Academic Family Medicine membership. The main arm of CERA is the infrastructure surrounding the development and dissemination of survey research. Each CERA survey consists of preset demographic questions and 5 modules with 10 questions each for a total of 50 study-specific questions; the distribution and length of the survey are designed to provide quality opportunities for research and improve response rate from these groups. Researchers can submit survey questions to be considered for inclusion in the omnibus survey. Common pitfalls of applications include repeating prior modules, poor survey question alignment with the research question, and an underdeveloped analytic plan. This manuscript provides a theoretical model to connect the research question, hypothesis, survey questions, and analytic plan for CERA survey research studies.

The Council of Academic Family Medicine (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) was established in 2011 to enhance the rigor and generalizability of family medicine educational research.1,2 CERA was created with three core components: (a) providing infrastructure for survey-based research, (b) connecting novice research teams with experienced mentors, and (c) supporting a repository of survey data. These components enable researchers to refine survey methodologies, analyze responses, and develop scholarly outputs such as conference abstracts and peer-reviewed publications.

CERA conducts surveys to gather insights on key issues in family medicine, focusing largely on education.3 These surveys sample family medicine residency directors, clerkship directors, department chairs, and the general CAFM membership.4,5,6 A structured schedule for survey distribution ensures consistency for the groups surveyed as well as for researchers interested in surveying certain populations. Table 1 presents the schedule of survey distribution for the four categories of respondents and average proposal acceptance rates. An important step for applicants is to select the appropriate survey group. Consider which group is the most knowledgeable about the topic and which group has access to the information. Also recommended is to apply the “pajama test” (would your survey group be able to answer the questions accurately while sitting on the couch, without having to look it up or phone a friend).

Survey type |

Frequency |

Call for proposals schedule |

Average proposal acceptance ratea |

Survey administered |

Average response ratesa |

Program director |

Twice a year |

Dec–Jan

Jun–Jul |

25% |

Apr–May

Nov–Dec |

49%

45% |

Clerkship director |

Once a year |

Jan–Feb |

57% |

Jun–Jul |

67% |

Department chair |

Once a year |

Mar–Apr |

60% |

Aug–Sep |

57% |

General membership |

Once a year |

May–Jun |

46% |

Sep–Oct |

35% |

Each omnibus survey consists of 5 modules with 10 questions each. Response rates also can be found in Table 1. Each independent CERA proposal for review may include up to 10 questions. CERA limits the number of questions to maintain brevity and encourage participation. For questions with “check all that apply” answer responses and for items in ranking tasks, each response is counted individually toward the total. Open-ended questions and matrix formats are not allowed. Further details and examples of how CERA questions are counted are available on the CERA website.7 Proposals are rigorously reviewed by two to three medical education experts and the survey chair, who evaluate each survey module proposal for inclusion in the omnibus survey. Acceptance rates vary based on the volume of proposals for the cycle.

Common pitfalls in CERA proposals include repetition of questions asked on previous surveys, an overly ambitious study design, and scope or feasibility issues related to the research question. CERA proposals that wish to repeat previous CERA survey questions should justify doing so, citing, for example, a significant event that may have altered present-day results compared to the past. Another pitfall includes inconsistency in survey question wording that deters researchers from making meaningful associations within data sets. Writing survey questions to compare independent and dependent variables yields a stronger proposal than designs that use only descriptive analyses. The ideal CERA survey study strikes a balance between being too narrow and too general, ensuring that results are widely applicable to family medicine education.

DESIGNING HIGH-QUALITY SURVEY RESEARCH

Creating a compelling research question is a critical first step in any research project. Identify a problem or gap in current educational practices or outcomes that the research team is passionate about exploring. Conduct a thorough literature review to understand what is already known about the topic. Past CERA survey topics are available on the CERA website; review these prior topics to see whether the topic has been previously addressed.8 If so, consider what additional information is needed or can be added to deepen knowledge of this topic.

Use the literature review to narrow the focus to a specific, manageable problem. Once the research team has a draft of the question, evaluate it using the FINER criteria: feasibility, interesting, novel, ethical, and relevance (Table 2). For example, for feasibility, ask, “Can the research question be answered within the limitations of CERA?”

FINER Criteria for Research Question Development |

Feasibility |

The question can be addressed given a 10-question survey.

Feasible: Understand the perceived level of importance, knowledge, and level of comfort that family physicians feel discussing menstrual health.

Not feasible: Understand the value of menstrual health discussions with family medicine patients. |

Interesting |

The question should be intriguing to the investigative team and audience.

Interesting: What are the effects of grade appeals on the clerkship director?

Not interesting: What is the pathway to anesthesia residency completion? |

Novel |

The question and hypothesis should not have been studied previously.

Review the prior CERA survey data and complete a brief literature review to identify publications and research in a similar area. |

Ethical |

The hypotheses and questions asked uphold the safety and well-being of the population being studied.

Questions that could place a chair, program director, or member of STFM at risk of being harmed (often psychologically) are not accepted by CERA. |

Relevance |

The research should add to the science of family medicine.

Relevance evolves; at the publication of this article, vaccine uptake in primary care is key. A relevant question may be, “What are the barriers to adult vaccination uptake (eg, shingles, pneumococcal) in patients aged 60+ in a family medicine clinic?” |

Next, seek feedback from colleagues and mentors from other institutions who can provide diverse perspectives and insights, including whether the topic is relevant to the broader family medicine community. Use their feedback to refine and improve the survey questions, ensuring that they are clear, focused, and aligned with the research goals.

Once the research question has been defined, ensure that the background information from the literature review supports a developed hypothesis. A hypothesis makes a clear prediction about the relationship between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables. Thus, a hypothesis is a statement that is explicitly designed to be tested using the results of the survey questions.

Research proposals may be framed as research questions or research aims. An example of an excellent aim can be found in the 2024 general membership survey: “To understand clinicians’ approaches to different models of cervical cancer screening for average risk persons aged 30–65 and to assess if there are any factors that correlate with their behavior.” This research question is feasible; many family physicians provide cervical cancer screening. It is interesting because the uptake of a US Preventive Services Taskforce recommendation has been low since its implementation. It is novel; it has yet to be addressed for family medicine clinicians. It is ethical as a routine part of care, and it is relevant because half of the population is indicated to have cervical cancer screening. Additionally, the aim specifies the study population—clinicians—and gives specificity to the intervention (age range, cervical cancer screening approaches). The aim builds to ask what factors impact behavior. The questions directly align with this aim. A poor version of this research aim might read, “Would educational modules improve uptake of alternative cervical cancer screening methods for family physicians?” In this question, the methods available to CERA would not fully answer the question. While clinicians may say, “yes, education would help,” the survey cannot directly test an educational module provided to clinicians. This question would be better tested in the practice-based research network setting rather than in a survey.

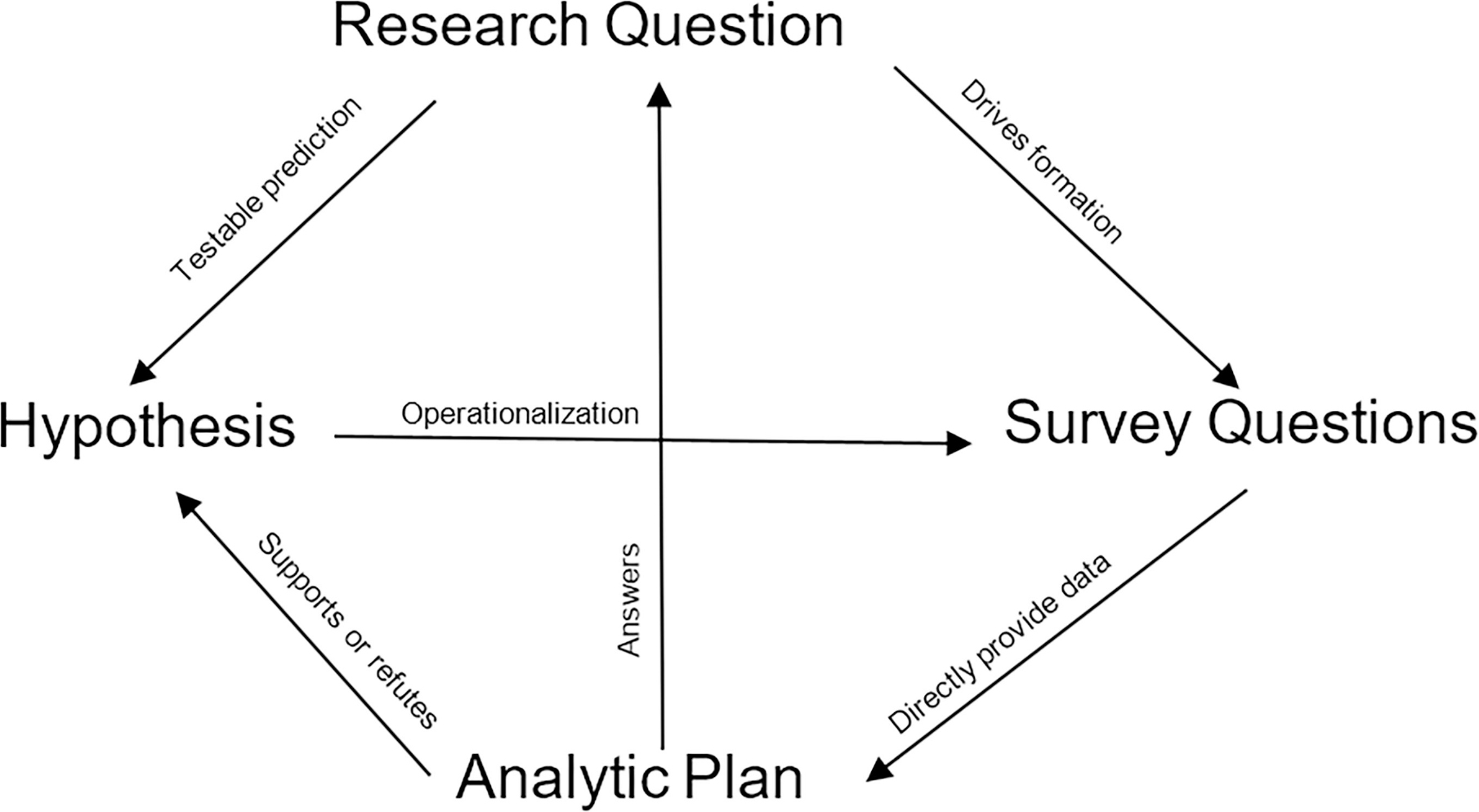

For another example, in the context of chronic pain management curricula in family medicine clerkships, a good hypothesis might be, “Clerkship directors with more experience treating chronic pain are more likely to teach chronic pain management.” This hypothesis suggests that an increase in the independent variable is expected to result in a corresponding increase in the dependent variable. A poor example of a question with the same intent would be, “Students who work with a physician who sees many chronic pain patients learn more about chronic pain.” The inverse statement here—that a physician inherently teaches high-evidence medicine if they see many patients with a concern—is not testable through CERA due to methodological challenges. Clerkship directors are able to respond with their own experience but cannot comment on whether students learned more from those who saw a high volume of chronic pain patients. Ultimately, a good hypothesis flows from having a well-defined research question that includes the variables to be studied, their potential relationships, and the target population (Figure 1).

The next step is developing effective survey questions, which is often the most challenging step. Key elements of an effective research question include a closed-ended format, clarity, relevance, translation into the variables used in the hypotheses, and response options that are comprehensive yet simple.9 Questions framed as double negatives are discouraged. For example, “Chronic pain management is not necessary in a family medicine curriculum.” If the respondent disagrees, they disagree with the negative statement, which can be confusing and certainly fails the pajama test. Some respondents may misinterpret their personal alignment given the double negative. A more reliable survey question would be, “On a scale of 1–10 (10 being most important), how important is chronic pain management as a component of the family medicine curriculum?” Lastly, questions that would result in the respondent answering only “yes” or “agree” do not generate useful information. For example, “Chronic pain management should be included in the family medicine curriculum,” and the respondent can either “agree” or “disagree.” Few to no respondents would respond “disagree,” and thus, this question does not meet a research objective.

Closed-ended format questions offer predefined response options and do not allow for free-form answers. One strategy to ensure that the questions are clear, understandable, and relevant is to pretest the questions with someone who has the same understanding and background as the survey respondents. Question response options need to be comprehensive to prevent respondents from answering, “My response option is not listed.” Additionally, avoiding compounding in response options is critical; for example, do not place two concepts that a respondent might answer “yes” to in one response option but “no” to the other in the same response option. Other considerations when forming research questions include (a) investigating whether validated questions for the topic already exist, and (b) avoiding questions that can be answered using other sources. Because the survey is designed to be done all in one sitting and by one person, questions should be easily answerable by the members of the group targeted by the survey. Another strategy to promote high-yield questions is to create a template of the final tables that would be presented in a manuscript. Each question, or question response option, should easily map to a variable within these tables; if it does not, then the question is likely not relevant.

A clearly articulated hypothesis or hypotheses that can be answered with the questions proposed is important to share before the analysis plan is presented. The hypothesis may be directional, rather than neutral. For example, “We hypothesize that resident implementation of chronic pain management improves with increased case-based educational sessions.” When drafting an analysis plan for a CERA survey research proposal, the independent and dependent variables must be clearly defined. The dependent variables should be measurable by the survey questions.

The research team may consider including someone skilled in statistics to assist with data analysis; if an expert in this capacity is not available, the CERA mentor can support this role. The statistical analysis should progress in stages, starting with descriptive statistics to summarize key findings, followed by bivariate analyses to explore relationships, and potentially multiple logistic regression for deeper insights. Identifying external data sources, such as the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) graduate survey and the Association of American Medical Colleges questionnaire, can provide valuable benchmarks for comparison and evaluation. To streamline interpretation, as mentioned earlier, researchers should create analysis tables in advance that outline potential associations, guiding subsequent statistical analyses and providing a well-structured approach to data interpretation.

Once each of the described elements is created, research teams should ensure that the proposal clearly delineates the importance of the topic, the research question, and the hypothesis. Overall, a CERA proposal should tell a cohesive story of the research question. What is the importance, where is the information gap, and how will the survey answer the question asked? The survey questions are crucial: recycle validated survey questions for components of the 10 questions, frame and field questions differently to identify biases in the responses, and ensure that each question provides novel information to contribute to the hypothesis. The methods of analysis should support the outcomes.

Once drafts of questions are accepted for inclusion in the omnibus survey, CERA matches research teams with mentors experienced in the CERA process. The mentors serve as direct members of the research team and enhance the survey study from planning through dissemination. These experts provide validation and refinement of study aims, hypotheses, and questions to ensure alignment. The finalized question module is then sent for additional review and revision.

Final question sets are sent to the CERA survey administrator, who compiles the survey questions into the dissemination software to display the question items in a way that does not skew answers, such as getting all question answers on the same page, using consistent ordering of answer responses, and fitting all answers in the same row. This draft survey is disseminated for pretesting on the platform to gather feedback from experts who are not in the current survey population (eg, the department chair survey is sent to past department chairs for feedback).3 These experts serve as external reviewers to the omnibus survey and provide feedback on item clarity, content relevance, response scales, and identification of missing content. This information is then provided back to the research team for further consideration. Once final question sets are accepted, the survey is sent for pilot testing among the CERA Steering Committee and the nonsample experts. Once all parties have accepted the survey, the omnibus survey is ready for dissemination to the sample population.

CERA surveys provide specific insight into the practices of family physicians, training pathways, and attitudes and culture of family medicine. A researcher can elicit valuable information with a well-framed proposal and a thoughtfully constructed question set. Proposals, though, are commonly too narrow in scope, do not propose new contributions to the literature, would not impact the broader family medicine educational community, or cannot be answered by the respondent. Review the literature and prior CERA surveys. Write a story with the background, hypothesis, and aims that directly link to the questions asked. Map the survey questions to outcomes and data tables that would answer the research questions posed.

In addition to these best practices, consider a few additional options. The CAFM team offers CERA data summaries to members. If a researcher finds a question bank from prior years that interests them, the full data are available to all CAFM members through the CERA portal after a 90 day embargo period. If you are struggling to put together a proposal or have been rejected in the past, consider requesting a CERA mentor. Mentors are recruited from prior CERA survey research teams, the CERA Steering Committee, and senior researchers from the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM), NAPCRG, ABFM, and the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors. Mentors can work with the team for a short duration or throughout the entire process, from proposal to manuscript publication. Finally, STFM and NAPCRG have collaborated to support Survey School, which assists members in designing surveys like CERA.

The CERA surveys were created to support family medicine research. While some proposals are not accepted on their first submission, many undergo review and are selected in the future. The goal of the research process is to encourage presentation and manuscript generation among family medicine scholars. The CERA Steering Committee welcomes feedback on the process and continues to improve the CERA methodology.

The author team acknowledges Lars Peterson for his continued efforts to improve survey science and the field of family medicine research, and for his outstanding contributions to the CERA committee.

References

-

Shokar N, Bergus G, Bazemore A, et al. Calling all scholars to the council of academic family medicine educational research alliance (CERA).

Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(4):372–373. doi:10.1370/afm.1283

-

Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW. Creating a centralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research.

Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257–260. doi:10.1370/afm.2228

-

-

Kost A, Ellenbogen R, Biggs R, Paladine HL. Methodology, respondents, and past topics for 2024 CERA clerkship director survey.

PRiMER. 2025;9. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2025.677955

-

Cordon-Duran A, Moore MA, Rankin WM, Biggs R, Ho T. Protocol for the 2024 CERA general membership survey.

PRiMER. 2025;9. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2025.436106

-

Paladine HL, Reedy-Cooper A, Rankin WM, Moore MA. Protocol for the 2024 CERA department chair survey.

PRiMER. 2025;9. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2025.600324

-

-

-

Wright KM, Gatta JL, Clements DS. Survey design for family medicine residents and faculty.

Fam Med. 2024;56(9):611. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2024.785866

There are no comments for this article.