Qualitative researchers embrace multiple ways of producing knowledge. Among the researchers using this transdisciplinary approach are clinicians, public health professionals, and social scientists. Qualitative researchers often draw on diverse social science and nursing traditions when collecting and reporting on qualitative data.1 Qualitative methods are a vibrant form of scientific inquiry; however, the range of knowledge, familiarity, and comfort with qualitative methods varies.2,3,4,5,6 Differences in understandings about how research produces new knowledge and how researchers can be sure of its rigor, which is defined differently in qualitative work (eg, reliability, validity, transparency), impact where qualitative findings are published and how the findings are structured.7,8,9,10 Knowing one’s audience and effectively communicating qualitative findings are essential to publishing articles. As social scientists with more than 4 decades of experience writing qualitative articles for health services audiences, we have developed strategies to publish our research.11 This brief article offers actionable tips on how to position qualitative research in communication across methods and disciplines.

BRIEF REPORTS

Writing Qualitative Research and Evaluation for Clinical Audiences

Jen M. van Tiem, PhD | Linda M. Kawentel, PhD | Gemmae M. Fix, PhD

Fam Med.

Published: 1/22/2026 | DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2026.972963

Qualitative methods draw from diverse traditions, from social science to nursing. Heterogeneity in approach and discipline make qualitative methodologies a vibrant form of scientific inquiry. At the same time, the range of knowledge, familiarity, and comfort with qualitative methods varies. The authors of this piece are social scientists with extensive qualitative writing experience, as well as experiences running writing groups, serving as peer reviewers, and being a journal editor. This brief article presents useful strategies and actionable tips for developing qualitative articles for peer-review and publication. It includes qualitative writing recommendations organized by (a) the common structure of qualitative articles, (b) the writing process, and (c) the end product and the peer review process. The authors’ goal is to provide accessible pathways for navigating qualitative article writing and publication for interdisciplinary audiences.

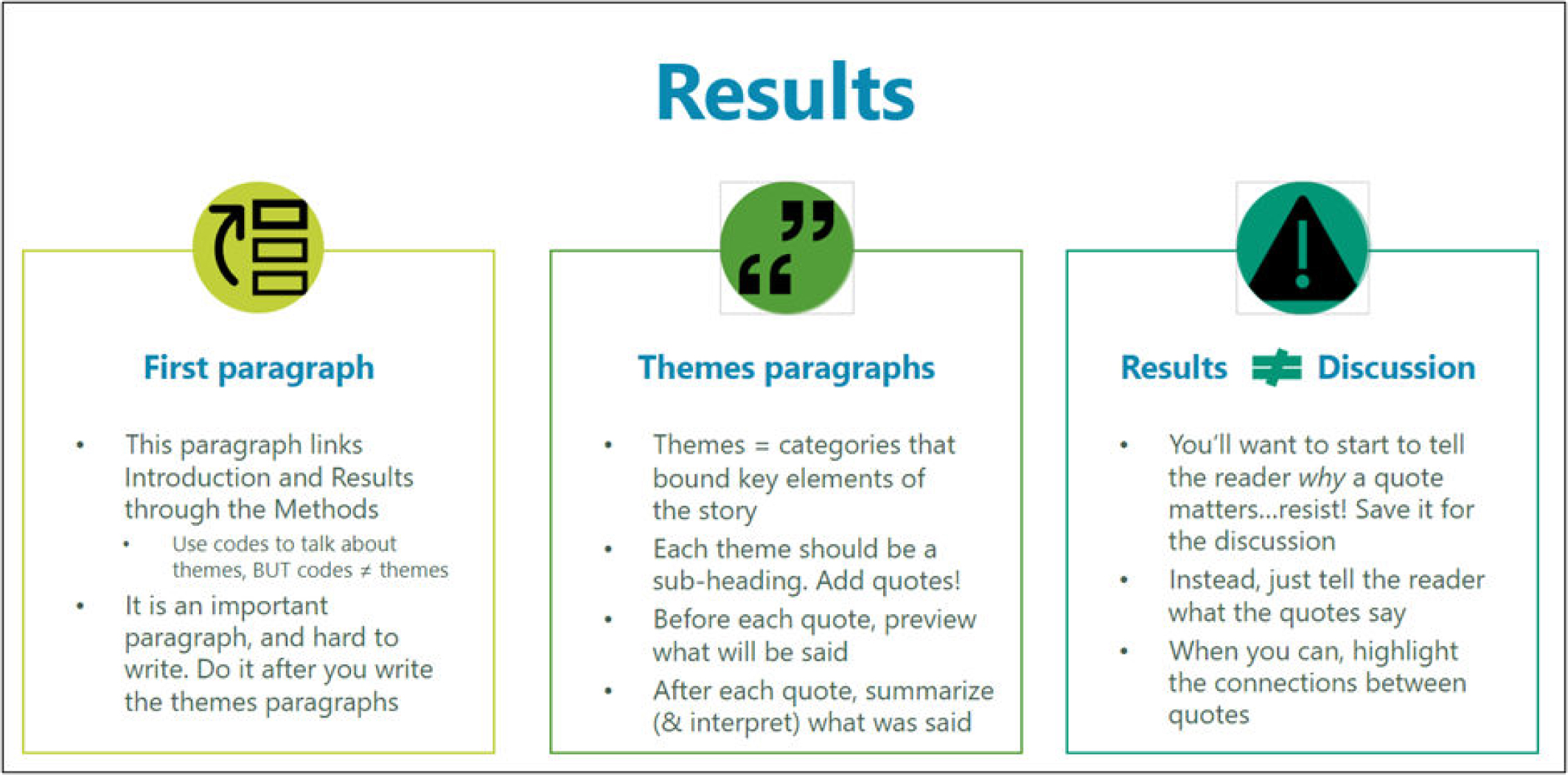

Medical and health services journals tend to have a uniform structure: introduction/background, methods, results/findings, discussion/conclusions.12 The introduction/background introduces the topic and includes (a) a description of what is known about the topic, (b) where there are gaps in knowledge, and (c) how this research addresses one or more of those gaps. For the methods section, qualitative checklists can provide guidance on what to include. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ)13 and standards for reporting qualitative research (SRQR)14 are commonly used. However, not all aspects of these checklists are appropriate to every article. The results/findings section follows the methods. It presents the results of the authors’ analysis and usually includes three to four takeaways that characterize themes or topics or narrative threads, along with data (eg, quotes) that provide evidence that illustrates the themes (Figure 1).

The discussion section synthesizes the gaps and data presented in the introduction and findings by (a) summarizing the themes or topics from the findings into a cohesive story (ie, with the discussion, you explain what the findings show), (b) describing how these findings confirm, compare and contrast, or extend what is already known about the topic, and (c) stating the “so what” of the article (ie, the top two reasons why the findings matter).

Conventions for reporting quantitative findings may influence how people write qualitative articles. Tables summarizing data are common in quantitative articles, because tables function as cognitive aids that show evidence for the argument. In contrast, putting qualitative data (ie, quotes) in tables may add to the cognitive load of the reader by fragmenting the evidence that supports the argument and decontextualizing the findings. Qualitative data are best presented integrated into the findings by showing the data and then describing what they mean.

Successful writers vary in how they approach the writing process; there is not one universal strategy.15 Similarly, qualitative writing may be approached in multiple ways. We have included some resources in the references list.16,17,18 Following are strategies that have worked for us.

Start with the methods. The methods offer an easier entree, either because they already have been written in a grant or proposal, or because they describe the steps the team undertook to collect and analyze data. Using the proposal as a prototype for the methods facilitates not having to start with a blank page. Drafting the methods can be started early in the project by keeping a running record of the procedures: what you did, when, and why.

Organize your data. Qualitative researchers develop and use a coding system to organize data.19 Coding systems facilitate pattern-based analytic techniques20 such as thematic analysis21 or content analysis.22 Researchers often use qualitative data analysis software (eg, NVivo [Lumivero], Dedoose, MAXQDA, ATLAS.ti [Limivero]) to digitize their coding system and organize their data. However, a person still needs to be actively engaged in the analysis process.

Iterate. Qualitative writing involves reading and rereading the data, organizing and reorganizing segments of data, and interpreting and reinterpreting the connections between segments of data. The work of thinking and writing yields a more refined understanding of the phenomena. Iteration is a necessary step in the data analysis process. Memoing23 during data collection and analysis can serve this purpose. The overlap between the analysis process and the writing process may feel unusual to those who are more familiar with quantitative analytic and writing techniques.

Write. The final written product likely will report on a subset of analytic insights. The categories or key points described in the findings section may not be specific codes in the codebook. However, describing the overall patterns that explain the phenomena of interest may help jump-start writing the findings section. A helpful question to ask yourself is “What are the three to four things I have learned that help me understand the problem or describe the phenomena?”

Different journals have different expectations for the content, format, and style of written products. Identifying a journal early in the writing process can save time and reduce rejection. To identify a journal, use any of several ways: (a) Find where similar articles are published by searching for key words in a scholarly database such as PubMed or Google Scholar; (b) review references in the article you are drafting; (c) use a tool. Many publishers offer tools to identify journals in their catalog. Alternatively, use a more general tool such as the Journal Author Name Estimator (JANE),24 which draws from journals indexed in PubMed.

Peer review is a process during which an article is closely reviewed by two to four people working in similar areas of expertise. You can help the editor identify qualified reviewers by using appropriate key words in the article or suggesting reviewers with qualitative expertise. Based on the reviewers’ own assessment of the work, the editor decides whether to reject, accept, or request “minor” or “major” revisions to the paper. If a journal recommends that you “revise and resubmit,” that likely means they are interested in your article and might accept it if you are responsive to the reviewers’ critiques. Include a “response to reviewer” table or letter, typically with each reviewer critique followed by your response. The Society for Teachers of Family Medicine provides a template for the response table as well as other resources.25

Reviewer critiques of qualitative articles often include questions about the methods. Qualitative studies appropriately use smaller sample sizes than quantitative studies. Instead of a focus on numbers, qualitative articles are assessed on the ability of the data to answer the research question. Qualitative researchers have developed standards for sufficient sample size (eg, 20–30 in a heterogenous sample),26 as well as conceptual frameworks to describe the quality of the data (eg, “information power”)27 as an analog to a power analysis. That said, conversation is ongoing about whether these metrics offer compelling ways to assess qualitative studies. Transparency in describing the methodological steps is key when establishing rigor. When responding to reviewers, ask your coauthors and colleagues for help, as well as for examples from their own efforts.

Writing can be challenging, and some may worry about their ability or skill. In addition to relying on the structure of the article, starting with the methods, spending time deliberately organizing your data, and embracing iteration, our last piece of advice is, if you get stuck, reframe the task. For some of us, thinking about dissemination is less about writing and more about putting a puzzle together. When in doubt, ask for help; reach out to a colleague and talk through an idea.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Content from this article was presented as “Engaging diverse audiences with your qualitative writing: strategies for health services and social science manuscripts, operational reports, and other products,” at the Advanced Qualitative Methods seminar hosted by the Qualitative Methods Learning Collaborative, December 8, 2022.

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Ann Arbor VAMC, Boston-Bedford VAMC, and Iowa City VAMC. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. There are no conflicts of interest to report for any authors.

References

-

Qualitative methods: what are they and why use them? Health Serv Res. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1101–1118.

-

On writing qualitative research. Read Res Q. 1996;31(1):114–120. doi:10.1598/RRQ.31.1.6

-

What Now and How? Publishing the Qualitative Journal Article. In: Faria R, Dodge M, eds. Qualitative Research in Criminology: Cutting-Edge Methods. Springer; 2022:241–253. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-18401-7_15

-

Writing up Qualitative Research. Fam Soc. 2005;86(4):589–593. doi:10.1606/1044-3894.3465

-

In: Writing Qualitative Research on Practice. Sense; 2009. 10.1163/9789087909086

-

Five steps to writing more engaging qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2018;17(1). doi:10.1177/1609406918757613

-

Five tips for writing qualitative research in high-impact journals. Int J Qual Methods. 2016;15(1). doi:10.1177/1609406916641250

-

Making meaning matter: An editor’s perspective on publishing qualitative research. J Gen Intern Med. 2024;39(2):301–305. doi:10.1007/s11606-023-08361-7

-

Strategies for communicating social science and humanities research to medical practitioners. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2022;23(2).

-

Writing a good read: strategies for re-presenting qualitative data. Res Nurs Health. 1998;21(4):375–382. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199808)21:43.0.CO;2-C

-

Engaging diverse audiences with your qualitative writing: strategies for health services and social science manuscripts, operational reports, and other products. VA Health Systems Research seminar; December 8, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=5255

-

The introduction, methods, results, and discussion (IMRAD) structure: A fifty-year survey. J Med Libr Assoc. 2004;92(3):364–367.

-

Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

-

Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

-

‘Write every day!’: A mantra dismantled. Int J Acad Dev. 2016;21(4):312–322. doi:10.1080/1360144X.2016.1210153

-

Fundamentals of Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide. Routledge; 2017. 10.4324/9781315231747

-

Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 4th ed. SAGE; 2017.

-

Sharing ethnographic findings. In: Hamilton AB, Fix GM, Finley EP, eds. Pragmatic Healthcare Ethnography: Methods to Study and Improve Healthcare. Routledge; 2024:97–118. 10.4324/9781003390657-5

-

The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 4th ed. SAGE; 2021.

-

Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern‐based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns and Psychother Res. 2021;21(1):37–47. doi:10.1002/capr.12360

-

Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

-

Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

-

Memoing in qualitative research: probing data and processes. J Res Nurs. 2008;13(1):68–75. doi:10.1177/1744987107081254

-

Welcome to Jane. https://jane.biosemantics.org

-

Revision response form for Family Medicine authors. https://journals.stfm.org/media/rxnfmos0/fmj-revision-response-form-2024.docx

-

How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. doi:10.1177/1525822X05279903

-

Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–1760. doi:10.1177/1049732315617444

Lead Author

Jen M. van Tiem, PhD

Affiliations: Center for Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation (CADRE), Iowa City Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Iowa City, IA | Department of Family and Community Medicine, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA

Co-Authors

Linda M. Kawentel, PhD - VA QUERI Center for Evaluation and Implementation Resources (CEIR), VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ann Arbor, MI

Gemmae M. Fix, PhD - Center for Health Optimization & Implementation Research (CHOIR), VA Bedford Healthcare System, Bedford, MA | Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, Boston University, Boston, MA

Corresponding Author

Gemmae M. Fix, PhD

Correspondence: Center for Health Optimization and Implementation Research, VA Bedford Healthcare System, Bedford, MA

Email: gmfix@bu.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.