Background and Objectives: The purpose of this study was to explore medical student perceptions of their medical school teaching and learning about human suffering and their recommendations for teaching about suffering. During data collection, students also shared their percerptions of personal suffering which they attributed to their medical education.

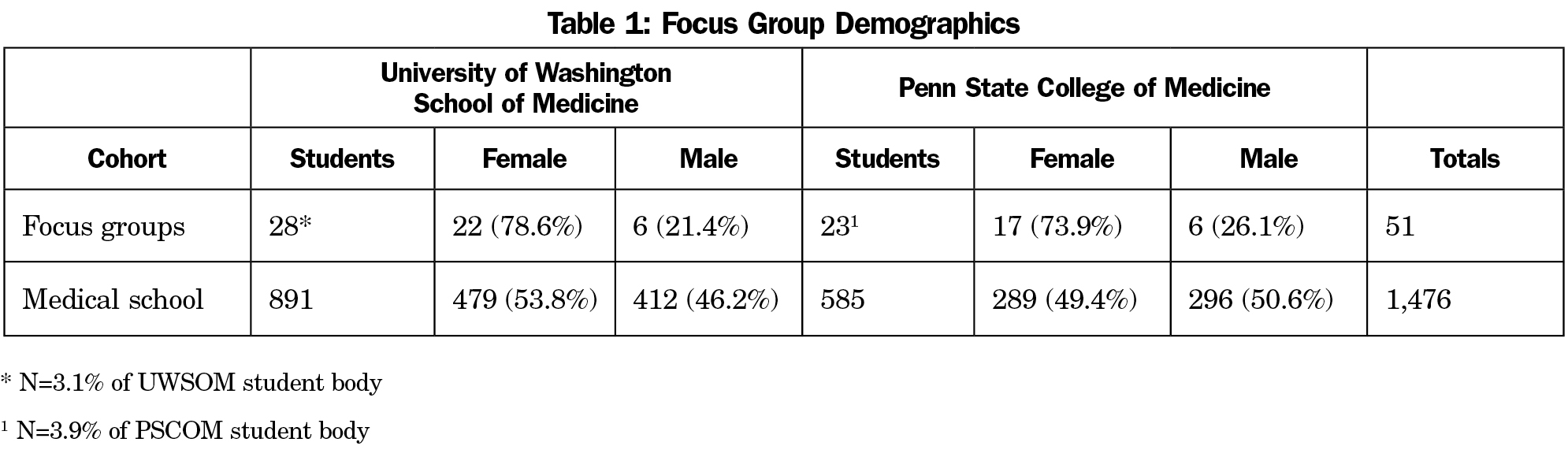

Methods: In April through May 2015, we conducted focus groups involving a total of 51 students representing all four classes at two US medical schools.

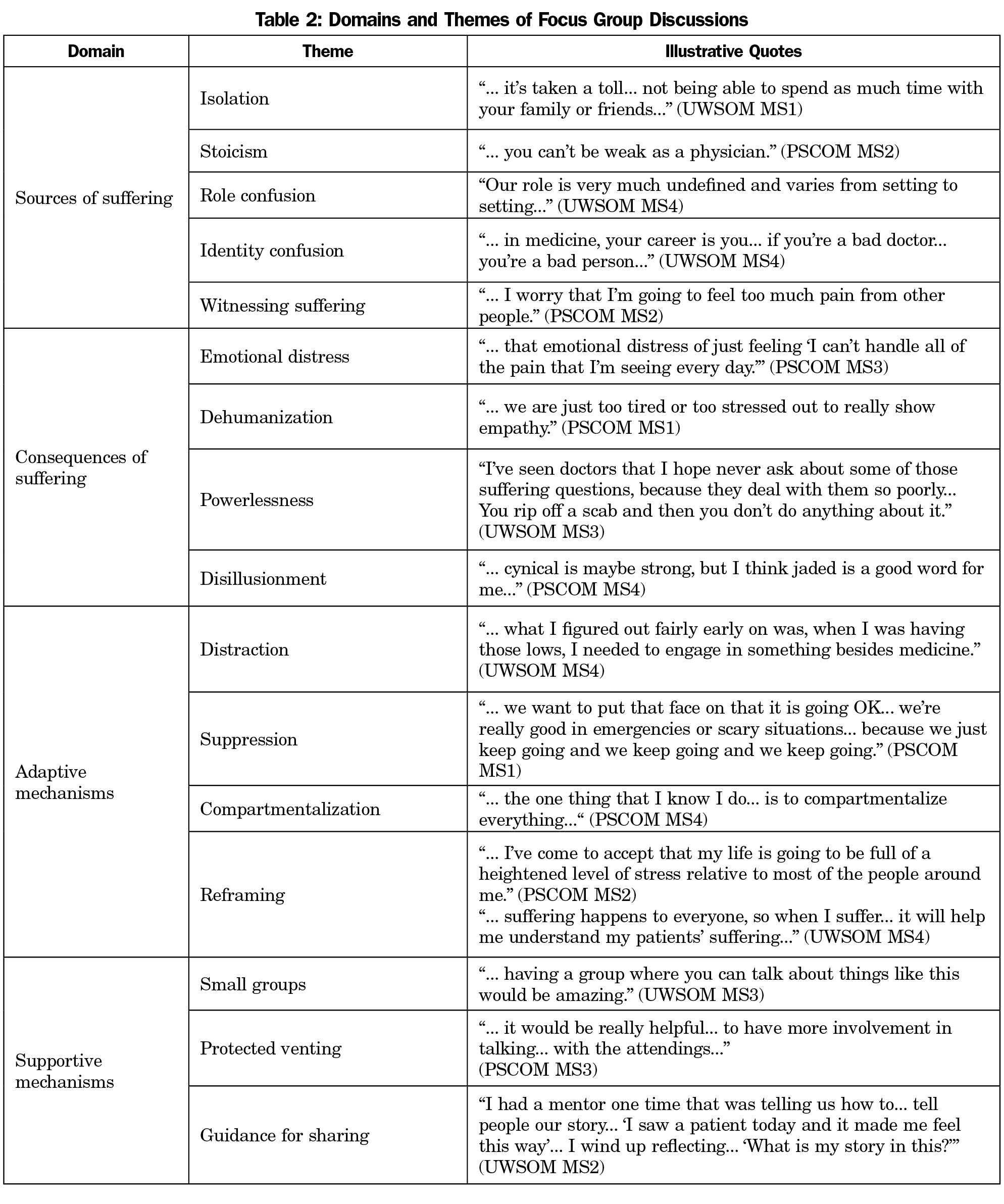

Results: Some students in all groups reported suffering that they attributed to the experience of medical school and the culture of medical education. Sources of suffering included isolation, stoicism, confusion about personal/professional identity and role as medical students, and witnessing suffering in patients, families, and colleagues. Students described emotional distress, dehumanization, powerlessness, and disillusionment as negative consequences of their suffering. Reported means of adaptation to their suffering included distraction, emotional suppression, compartmentalization, and reframing. Students also identified activities that promoted well-being: small-group discussions, protected opportunities for venting, and guidance for sharing their experiences. They recommended integration of these strategies longitudinally throughout medical training.

Conclusions: Students reported suffering related to their medical education. They identified common causes of suffering, harmful consequences, and adaptive and supportive approaches to limit and/or ameliorate suffering. Understanding student suffering can complement efforts to reduce medical student distress and support well-being.

Medical training stresses medical students, who negotiate a rigorous curriculum while struggling with the emotional demands of clinical care.1-4 Students enter medical school with better mental health than nonmedical peers but graduate with greater levels of depression and burnout, indicating medical education theatens student well-being.5 Little is known, however, about whether students perceive themselves to suffer as a result of their medical training.

Suffering is “an aversive emotional experience characterized by the perception of personal distress that is generated by adverse factors undermining the quality of life”6 that arises when events are perceived to threaten the integrity of the self.7 As such, suffering involves “dissolution, alienation, loss of personal identity and/or a sense of meaninglessness”8 and is an existential experience with subjective meanings and spiritual dimensions for the sufferer.9,10

While exploring medical student perceptions of their education about suffering,11 some participants reported personal suffering they attributed to their medical education. What they expressed differed from anxiety, depression, and burnout, as our students rarely used those terms. Rather, their suffering involved the culture of medical education and the personal transformation to physicianhood. This report summarizes these perceptions of student suffering and the activities that provided relief.

In April through May 2015, we conducted focus groups with students from each year of study at the University of Washington School of Medicine (UWSOM) and Penn State College of Medicine (PSCOM). We emailed invitations to all registered students to “participate in a research study to better understand medical student education about human suffering.” Participants gave informed consent and received a $10 gift card. We enrolled volunteers to fill an optimal size of 4 to 10 per group.12 Each school’s institutional review board approved our study protocol.

The authors facilitated groups at their respective institutions. We analyzed verbatim discussion transcripts using standard qualitative procedures, including an iterative, dialectical approach to coding, a constant comparison method,13 and an anonymous member check survey. We reported our methods in detail elsewhere.11

We analyzed student reports concerning personal suffering they attributed to medical education, including comments on the member check survey, using procedures similar to our initial analysis and informed by literature about suffering.

Fifty-one students participated in eight groups (Table 1). Women were disproportionately represented relative to medical school demographics. Students described aspects of their medical education contributing to their suffering, the resultant consequences, their efforts to adapt, and their perceptions of what helped limit or ameliorate their suffering (Table 2).

Sources of Suffering

The demands of medical school isolated students from meaningful connections to family and friends. They perceived that the culture of medical education encouraged stoicism, particularly in the clinical years, and noted that their roles were often ill-defined with unclear expectations. Students suffered when their professional identity became confused with their personal identity, and work performance was equated to personal worth. Witnessing suffering in patients, families and colleagues wrought suffering among students.

Consequences of Suffering

These educational stressors created considerable emotional distress. Some participants worried about losing touch with their humanity and altruism, and they felt powerless to ameliorate the suffering they witnessed. Observing suffering that was inadequately addressed left some disillusioned with medicine.

Adaptive Mechanisms

Students used distractions to divert their attention from the pressures of medical training. Some suppressed and compartmentalized their emotions to avoid discomfort. Others reframed their experiences to gain acceptance of and find meaning in their suffering.

Supportive Mechanisms

Students valued the support they received from preclinical small group sessions and self-care experiences and lamented that these waned as clinical exposure to suffering increased. They described the value of safely venting their distress and desired guidance for how to share their uncertainties, frustrations, and fears.

The struggles our students described embody the classic themes associated with suffering—isolation, hopelessness, helplessness, and loss,14 suggesting threats to their personal integrity congruent with the literature about suffering.7,8,15-17 Medical training tested our participants’ cognitive and affective capacities while isolating them from sources of support. Clinical training challenged their concepts of self and beliefs about medicine,18 triggering existential angst. Students who reported disillusionment with medicine may have implied a spiritual dimension to their suffering, but none explicitly mentioned this domain.

The adaptive mechanisms our students described align with Gross’ conceptions of emotional regulation,19 strategies by which individuals seek to control emotions. Our participants described regulatory processes of attention deployment (distraction), response modulation (suppression/compartmentalization), and cognitive change (reframing).4 Of these, reframing may be most beneficial, as suffering can be endured and alleviated through acceptance and investiture with meaning.20,21

Reframing—changing the appraisal of a situation—facilitates acceptance of and finding meaning in experience, both of which have been shown to reduce student distress. Teaching medical students to nonjudgmentally observe their experience through mindfulness meditation reduced their stress.22,23 Workshops developing personal insight and confronting suffering helped students discover deeper meaning in medicine.24 That student distress is relieved through practices known to alleviate suffering suggests that suffering may be a discrete student stressor.

As for supportive mechanisms that helped decrease suffering, students favor sharing emotions with peers undergoing similar experiences.25 Extending small groups and mentoring throughout clinical training would sustain preclinical initiatives and provide a forum for guiding students through the nuances of managing suffering. E-conferencing could help students in decentralized training sites debrief stressful experiences and receive support similar to what practicing physicians have experienced in Balint groups.26 Reflective activities that increased student insight regarding themselves and others could generate constructive meaning to their suffering.24,27

Our data documents that some medical students perceive they suffer as a result of their medical education. Our participants were a small percentage of students from two medical schools. Being volunteers, they likely had special interests in suffering. Their perceptions may not represent their classmates or other medical students. Their comments may reflect recall bias, and we cannot confirm their reports.

Further research is needed to determine the relationship between medical student emotions and suffering. Mixed-methods studies using qualitative methods to explore student suffering, standardized measures of anxiety, depression and burnout, and quantitative measures of prevalence and associated factors would be valuable.

We believe some degree of suffering is inherent to the personal and professional development of future physicians and may provide opportunities to help them become better doctors. Guiding students in processing their suffering, providing supportive networks to share their perceptions and feelings, and helping them to find positive meaning in their experiences may help to limit or alleviate their suffering. In the process, students may find deeper meaning in their work and be better prepared for patient care.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Center for Leadership and Innovation in Medical Education (CLIME) at the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA.

References

- Wear D. “Face-to-face with It”: medical students’ narratives about their end-of-life education. Acad Med. 2002;77(4):271-277.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200204000-00003.

- Egnew TR, Lewis PR, Schaad DC, Karuppiah S, Mitchell S. Medical student perceptions of medical school education about suffering: a multicenter pilot study. Fam Med. 2014;46(1):39-44.

- Monrouxe LV, Rees CE, Endacott R, Ternan E. ‘Even now it makes me angry’: health care students’ professionalism dilemma narratives. Med Educ. 2014;48(5):502-517.

https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12377.

- Doulougeri K, Panagopoulou E, Montgomery A. (How) do medical students regulate their emotions? BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):312.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0832-9.

- Brazeau CM, Shanafelt T, Durning SJ, et al. Distress among matriculating medical students relative to the general population. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1520-1525.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000482.

- Cherny NI, Coyle N, Foley KM. Suffering in the advanced cancer patient: a definition and taxonomy. J Palliat Care. 1994;10(2):57-70.

- Cassel EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. N Engl J Med. 1982;306(11):639-645.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198203183061104.

- Coulehan J. Suffering, hope, and healing. In: Moore RJ, ed. Handbook of pain and palliative care: biobehavioral approaches for the life course. New York, NY: Springer; 2013:717-731.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1651-8_37.

- Kearney M. Mortally Wounded: Stories of Soul Pain, Death and Healing. Dublin: Marino Books; 1996.

- Wright LM. Suffering and Spirituality: The Path to Illness Healing. Calgary, AB: 4th Floor Press; 2017.

- Egnew TR, Lewis PR, Myers KR, Phillips WR. Medical student perceptions of their education about suffering. Fam Med. 2017;49(6):423-429.

- Parsons M, Greenwood J. A guide to the use of focus groups in health care research: Part 1. Contemp Nurse. 2000;9(2):169-180.

https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2000.9.2.169.

- Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230153.

- Kearsley JH. Therapeutic use of self and the relief of suffering. Cancer Forum 2010;34(2). https://cancerforum.org.au/forum/2010/july/therapeutic-use-of-self-and-the-relief-of-suffering/. Accessed April 27, 2017.

- Kahn DL, Steeves RH. An understanding of suffering grounded in clinical practice and research. In: Ferrell BR, ed. Suffering. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 1995:3-15.

- Reed FC. Suffering and illness: insights for caregivers. Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis Company; 2003.

- Mount BM, Boston PH, Cohen SR. Healing connections: on moving from suffering to a sense of well-being. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(4):372-388.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.014.

- Landis DA. Physician distinguish thyself: conflict and covenant in a physicians’ moral development. Perspect Biol Med. 1993;36(4):628-641.

https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.1993.0032.

- Gross JJ. The emerging field of emotion regulation: an integrative review. Rev Gen Psychol. 1998;2(3):271-299.

https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271.

- Hayes SC, Smith S. Get out of your mind and into your life: the new acceptance and commitment therapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2005.

- Frankl VE. Man’s search for meaning: an introduction to logotherapy. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 2006.

- Rosenzweig S, Reibel DK, Greeson JM, Brainard GC, Hojat M. Mindfulness-based stress reduction lowers psychological distress in medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2003;15(2):88-92.

https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328015TLM1502_03.

- Hassed C, de Lisle S, Sullivan G, Pier C. Enhancing the health of medical students: outcomes of an integrated mindfulness and lifestyle program. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2009;14(3):387-398.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-008-9125-3.

- Kearsley JH, Lobb EA. ‘Workshops in healing’ for senior medical students: a 5-year overview and appraisal. Med Humanit. 2014;40(2):73-79.

https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2013-010438.

- de Vries-Erich JM, Dornan T, Boerboom TBB, Jaarsma ADC, Helmich E. Dealing with emotions: medical undergraduates’ preferences in sharing their experiences. Med Educ. 2016;50(8):817-828.

https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13004.

- Balint M. The doctor, his patient and the illness. New York, NY: International Universities Press; 1972.

- Sandars J. The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 44. Med Teach. 2009;31(8):685-695.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590903050374.

There are no comments for this article.