Background and Objectives: Careful assessment of depression and suicidality are important given their prevalence and consequences for quality of life. Our study evaluated the impact of an educational intervention in a family medicine residency clinic on rates of provider documentation regarding suicidality.

Methods: We offered two brief workshops to our clinic staff and created two standardized charting templates to empower and educate providers. One template used with the patient during the clinic visit elicited key factors (eg, plan, intent, barriers) and offered treatment plan options. The second template included supportive text and resources to include in the after-visit summary. A chart review was completed, examining 350 patient records in which the patient reported thoughts of death or suicide in the preceding 2 weeks on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 ([PHQ-9], 150 over a 5-month baseline period, 150 in months 1 through 4 immediately following the workshops and template development, and 50 at follow-up months 7 through 8 following the intervention). We examined use of the templates and changes in rates of documentation of suicidality.

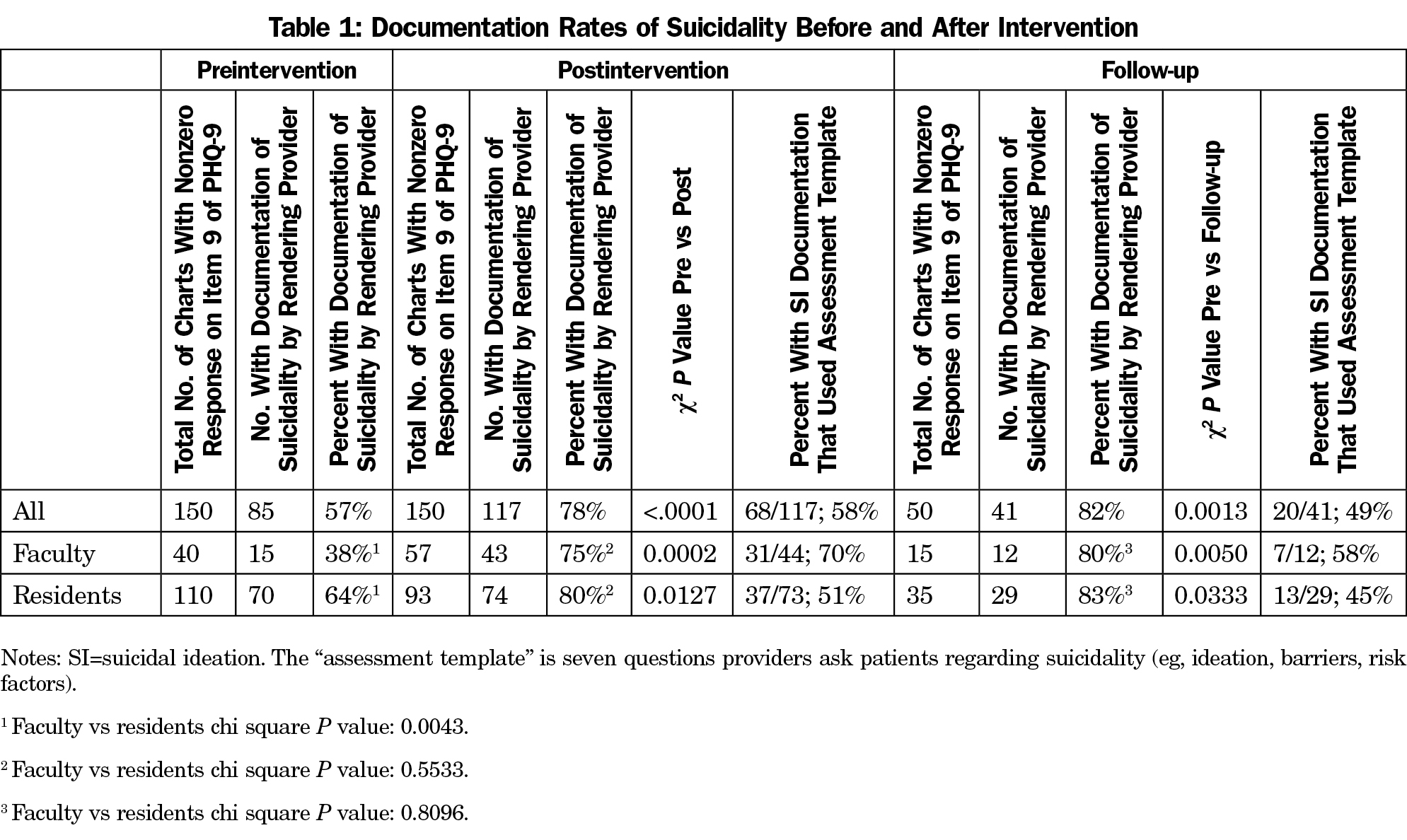

Results: Rates of provider documentation of suicidality for patients who had expressed suicidal ideation on the PHQ-9 increased significantly from 57% at baseline to 78% in the postintervention phase; the rise persisted at follow-up. Rates of use of the assessment template were 58% (postintervention) and 49% (follow-up). Anecdotal provider feedback reflected appreciation of the templates for assessing and documenting challenging issues.

Conclusions: Brief educational interventions were associated with improved rates of provider documentation of suicidality. The longer-term impact of the workshops and templates warrant further investigation.

Depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide and is a major contributor to the overall global burden of disease.1 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for depression in adults, followed by structures to support accurate clinical diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up care.2 Of particular concern among patients experiencing depression is the elevated risk of suicide, which is the tenth leading cause of death in the United States. Family physicians provide a large share of the mental health treatment in our country,4 and nearly half of people who complete suicide have seen a health care provider within a month prior to death.5

Standard work in our family medicine residency (FMR) clinic involves medical assistants verbally administering the two-item version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)6 to all adult patients; patients who answer affirmatively to either item complete a paper copy of the PHQ-9. The extent to which our providers reviewed the PHQ-9 results and discussed them with their patients was uncertain, especially item nine that assesses the frequency of “thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way” in the past 2 weeks. Answers on this item range from 0 (not at all) to 1 (several days), 2 (more than half the days), and 3 (nearly every day). Open discussion and documentation of suicidality is important for several reasons, even beyond the disrespectful message that failure to do so sends to patients who express these feelings. First, large-scale research has found that a positive response to item 9 is a strong predictor of suicide attempts and death in the following 2 years.7 Secondly, research has found that patients whose PHQ-9s were addressed by their PCP were twice as likely to follow up.8 Third, a provider may be at elevated risk for a malpractice claim if a patient has reported thoughts of suicide on the PHQ-9 and the provider failed to address and document a clinical discussion and appropriate treatment plan.9

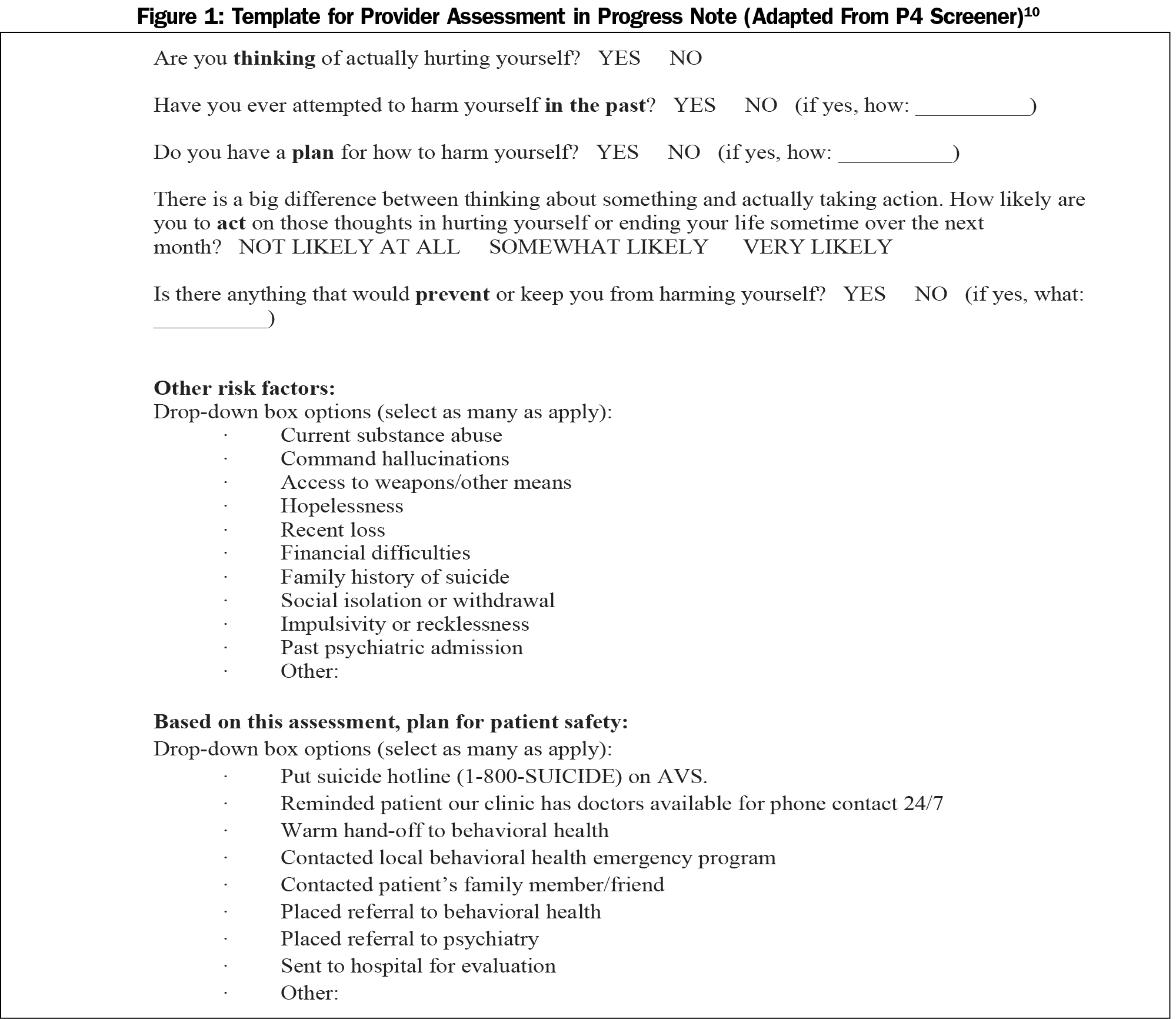

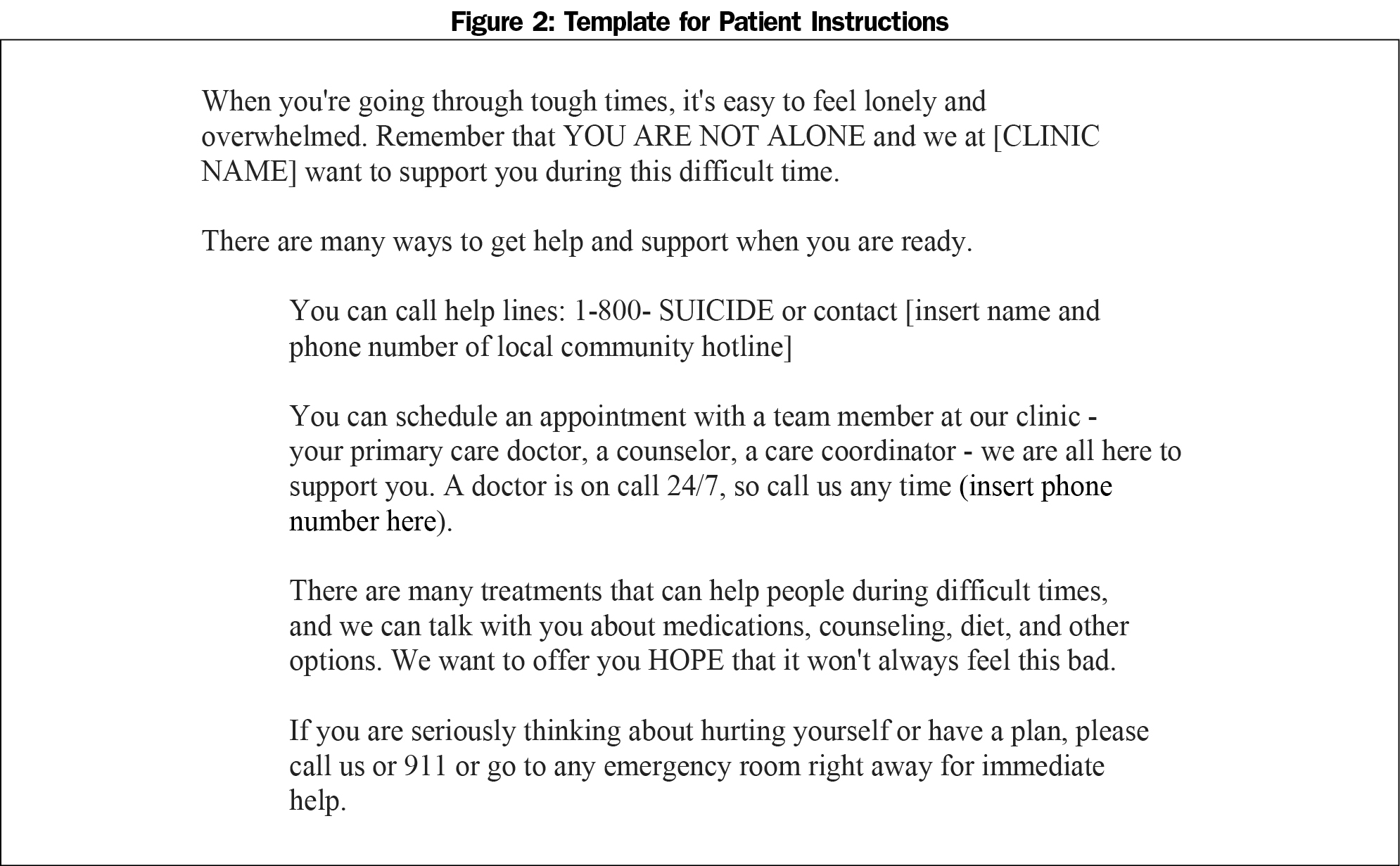

We developed a two-part educational intervention to raise awareness of depression/suicide and to increase appropriate documentation. First, we presented two 1-hour clinic-wide trainings during consecutive weekly staff meetings. Trainings addressed detection of depression/suicide, obstacles to open discussion, scripts to engage patients in these discussions, and standard work for PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 administration; PowerPoint slides are available here: https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/suicide-assessment. Secondly, we created two templates for providers. The first is a modification and expansion of the P4 Screener,10 in which we assess suicidal ideation (SI), past self-harm, plan, intent, and barriers (Figure 1). We added two questions that assess 10 other risk factors (eg, substance abuse, hallucinations, bereavement) and eight options for plans for patient safety (eg, warm handoff to behavioral health, referral to psychiatry, psychiatric admission). The second template is supportive text including community resources for the patient instructions (Figure 2).

The objective of this study was to assess the impact of these educational interventions on provider documentation of suicidality. We hypothesized that documentation rates would increase after our intervention.

Our urban family medicine residency (FMR) program has 30 residents and 16 physician or nurse practitioner faculty, all of whom had patient encounters during this time period with a nonzero response to item nine. Across faculty and residents, 16 providers (35%) were male.

A chart review was conducted of 350 patient records in which the patient reported some thoughts of death or suicide in the preceding 2 weeks on the PHQ-9 (a nonzero response to item nine), including 150 over a 5-month baseline period, 150 during the postintervention period (months 1 through 4 immediately following the workshops/template development), and 50 during the follow-up period (months 7 and 8 after the intervention). The first author reviewed the provider progress note corresponding to the date the PHQ-9 was administered. Chart documentation of anything regarding suicidality was deemed a “yes.” Chi-square tests and two-sample t-tests were used to examine changes in documentation patterns. The project was reviewed by our university IRB and deemed exempt.

Rates of provider documentation of suicidality increased significantly from 57% at baseline to 78% in the postintervention phase (P<.0001); rate at follow-up was 82% (see Table 1). Documentation rates among residents were higher than faculty during the preintervention phase (P=.004), but there were no significant differences by role (resident vs faculty) in the other phases. During all phases, likelihood of provider suicide documentation was not significantly related to the frequency of patients’ thoughts of death or suicide (item nine).

For patient charts with documentation of suicidal ideation, rates of use of the assessment template were 58% (postintervention) and 49% (follow-up).

Our educational interventions were associated with significantly increased rates of provider documentation of suicidality from the baseline to the postintervention periods, a rise which persisted to 8 months following intervention. About half of the charts utilized the new templates. Informal provider feedback supports these findings; residents and faculty shared that the templates increased their self-efficacy and comfort in talking with patients about suicidal thoughts and in documenting treatment recommendations. Given the high rates of and burden associated with depression and the elevated risk for self-harm among patients who endorse item nine, it is incumbent upon physicians to effectively use the PHQ-9 and talk with patients about depression and suicide.

A limitation of this study is uncertain generalizability due to the sample being drawn from one FMR clinic. The extent to which observed changes may have been affected by time of year is unknown. Further, the extent to which the increased documentation rates were due to the clinic workshops vs the new templates is unknown.

However, these findings offer preliminary support for the effectiveness of our educational interventions in shaping an important provider behavior. Future research could include a longer follow-up period to monitor rates of documentation and use of templates, implementation of these educational interventions in another setting, exploring provider self-efficacy with managing suicidal patients, and eliciting patient feedback on their experience of providers’ approaches to assessing suicidal ideation.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Samantha Carlson, MPH. Support provided by Research Services, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota.

References

- World Health Organization. Depression fact sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/. Accessed May 7, 2017.

- Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Screening for depression in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(4):380-387.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.18392.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National Center for Health Statistics. Increase in Suicide in the United States, 1999–2014. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db241.htm#ref3/. Accessed May 7, 2017.

- Olfson M, Kroenke K, Wang S, Blanco C. Trends in office-based mental health care provided by psychiatrists and primary care physicians. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(3):247-253.

https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13m08834.

- Ahmedani BK, Simon GE, Stewart C, et al. Health care contacts in the year before suicide death. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):870-877.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2767-3.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

- Simon GE, Coleman KJ, Rossom RC, et al. Risk of suicide attempt and suicide death following completion of the Patient Health Questionnaire depression module in community practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(2):221-22.

https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.15m09776.

- Tiemstra JD, Fang K. Depression screening in an academic family practice. Fam Med. 2017;49(1):42-45.

- Bryan CJ, Rudd MD. Managing Suicide Risk in Primary Care. New York City: Springer Publishing Company; 2010.

- Dube P, Kroenke K, Blair MJ, Theobald D, & Williams LS. The p4 screener: Evaluation of a brief measure for assessing potential suicide risk in 2 randomized effectiveness trials of primary care and oncology patients. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(6):PCC.10m00978.

There are no comments for this article.