Family physicians care for patients of all ages with undifferentiated chronic and acute conditions, making uncertainty inherent in daily practice.1,2 Complexity of care provided per hour in family practice is 33% higher than that in cardiology and five times higher than that in psychiatry.3 Family physicians value both the breadth of care and its implicit uncertainty, which they consider part of their identity.4 Further, family medicine residents must learn to become skilled physicians while managing clinical uncertainty. One study found that intolerance of ambiguity decreases with each year of residency training.5 Formal training might increase tolerance for uncertainty6; thus, the addition of a curriculum targeting ambiguity is worthwhile.7-9 We conducted an in-depth assessment of a novel outpatient curriculum to determine if we could influence family medicine residents’ tolerance of ambiguity.

BRIEF REPORTS

A Pilot Study to Address Tolerance of Uncertainty Among Family Medicine Residents

Deborah Taylor, PhD | Bethany Picker, MD | Donald Woolever, MD | Erin K. Thayer, BA | Patricia A. Carney, PhD | Ari B. Galper, BA

Fam Med. 2018;50(7):531-538.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2018.634768

Background and Objectives: Because patients often present to their family physicians with undifferentiated medical problems, uncertainty is common. Family medicine residents must manage both the ambiguity inherent in the field as well as the very real uncertainty of learning to become a skilled physician with little experience to serve as a guide. The purpose of this analysis was to assess the impact of a new curriculum on family medicine residents’ tolerance of ambiguity.

Methods: We conducted an exploratory quasi-experimental study to assess the impact of a novel curriculum designed to improve family medicine residents’ tolerance of ambiguity. Four different surveys were administered to 25 family medicine residents at different stages in their training prior to and immediately and 6 months after the new curriculum.

Results: Although many constructs remained unchanged with the intervention, one important construct, namely perceived threats of ambiguity, showed significant and sustained improvement relative to before undertaking this curriculum (score of 26.2 prior to the intervention, 22.1 immediately after, and 22.0 6 months after the intervention).

Conclusions: A new curriculum designed to improve tolerance to ambiguity appears to reduce the perceived threats of ambiguity in this small exploratory study.

The Central Maine Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board reviewed study activities and deemed it exempt. An exploratory quasi-experimental pre/post design was used to assess the impact of a new curricular experience where 4-week outpatient family medicine-teaching (OPFM-T) rotations were embedded into each year of residency training. We considered this study a pilot because we had not conducted a study like this previously, were unsure of its feasibility, and we did not have effect size data upon which to base power calculations.

The Educational Program

Despite different educational offerings during each year of training, overarching goals and measures for each OPFM-T were the same. Goals included increasing tolerance of ambiguity, competence, and confidence in caring for diverse, complex patient populations in ambulatory settings. The educational program was geared toward the learner’s level of development and milestone expectations. Program curricula included specific readings, reflective writing, discussion, and ambulatory skill development using psychosocial/behavioral health tools and enhanced electronic health records. OPFM-T blocks differed from other OPFM blocks in that each resident spends 50% of their time in clinic each half day of the rotation along with 50% in formal educational sessions. Please see Appendix A (https://journals.stfm.org/media/3249/taylor-appendixa-fm2018.pdf) for detailed information about OPFM-T.

Data Collection

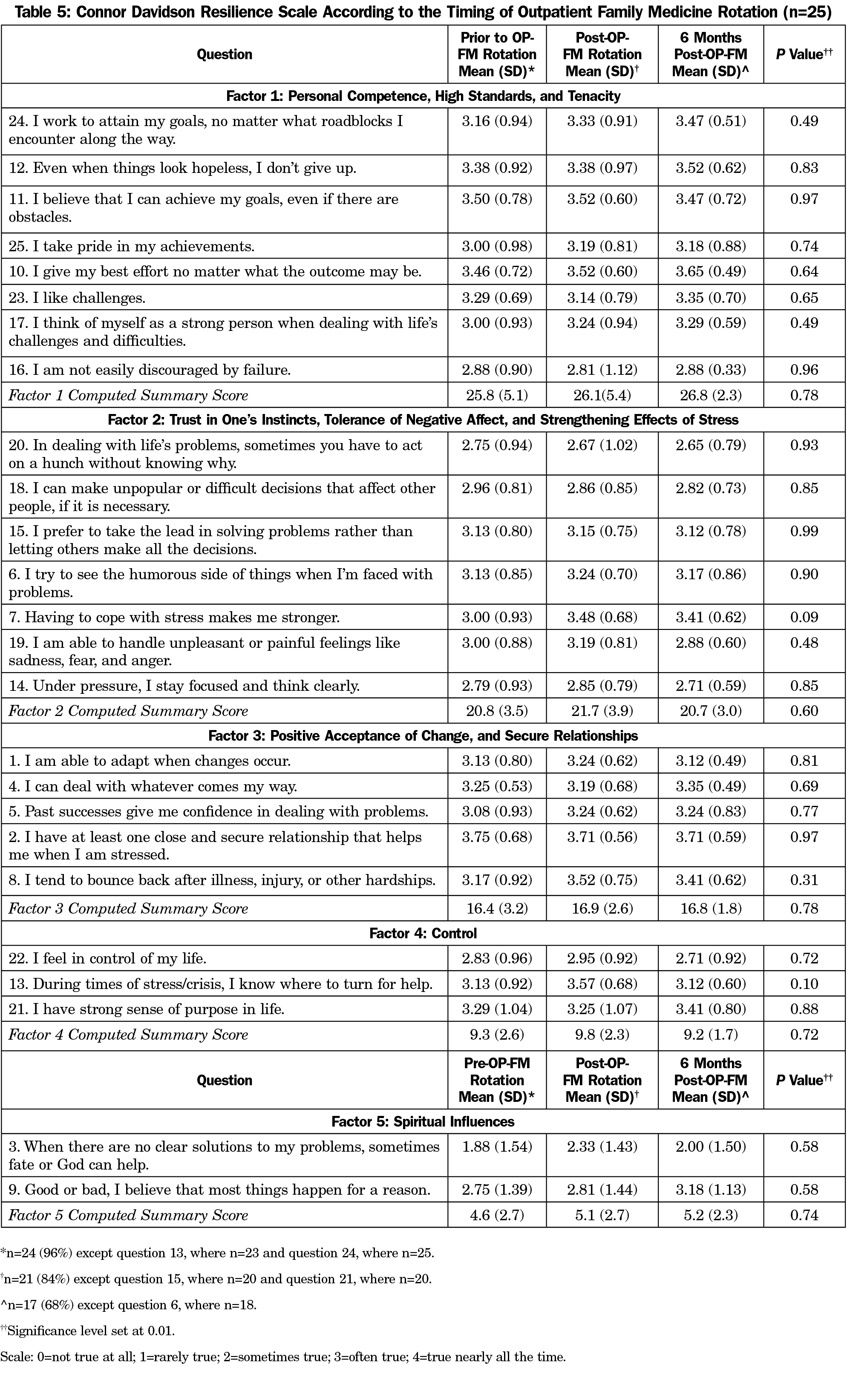

Data were collected using four surveys: (1) Physicians’ Reaction to Uncertainty Scale (PRUS) with reported Cronbach alpha coefficients of 0.74 to 0.8510; (2) Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (IUS), with reported Cronbach’s alphas of 0.94 to 0.9611; (3) Budner’s Intolerance for Ambiguity Scale (BIAS), with reported alpha coefficients between 0.63 and 0.6412,13; and (4) Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) with reported alpha coefficient of 0.89.14 A review of the literature, which indicates subtle differences exist between tolerance of ambiguity and tolerance of uncertainty, led us to utilize a scale for each, and the PRUS was selected because it is physician-centric.8 These surveys were administered to residents once pre-OPFM-T and twice post-OPFM-T at two different time points. Time was protected on the last afternoon of the 4-week rotation to complete the first post-OPFM-T survey. The pre- and post-OPFM-T surveys were distributed to residents without protected time for completion, but a clear return date was provided.

Data Analysis

Characteristics of study participants were assessed using descriptive statistics. Scaled variables from each survey were scored according to described methods10-14 for summarizing factor or construct scores, handling missing items, and reverse scoring. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare individual variables and subscale scores for all surveys. Though this was a pilot study, we set our alpha level at .01 to account for multiple comparisons. SPSS version 24 was used for analyses.

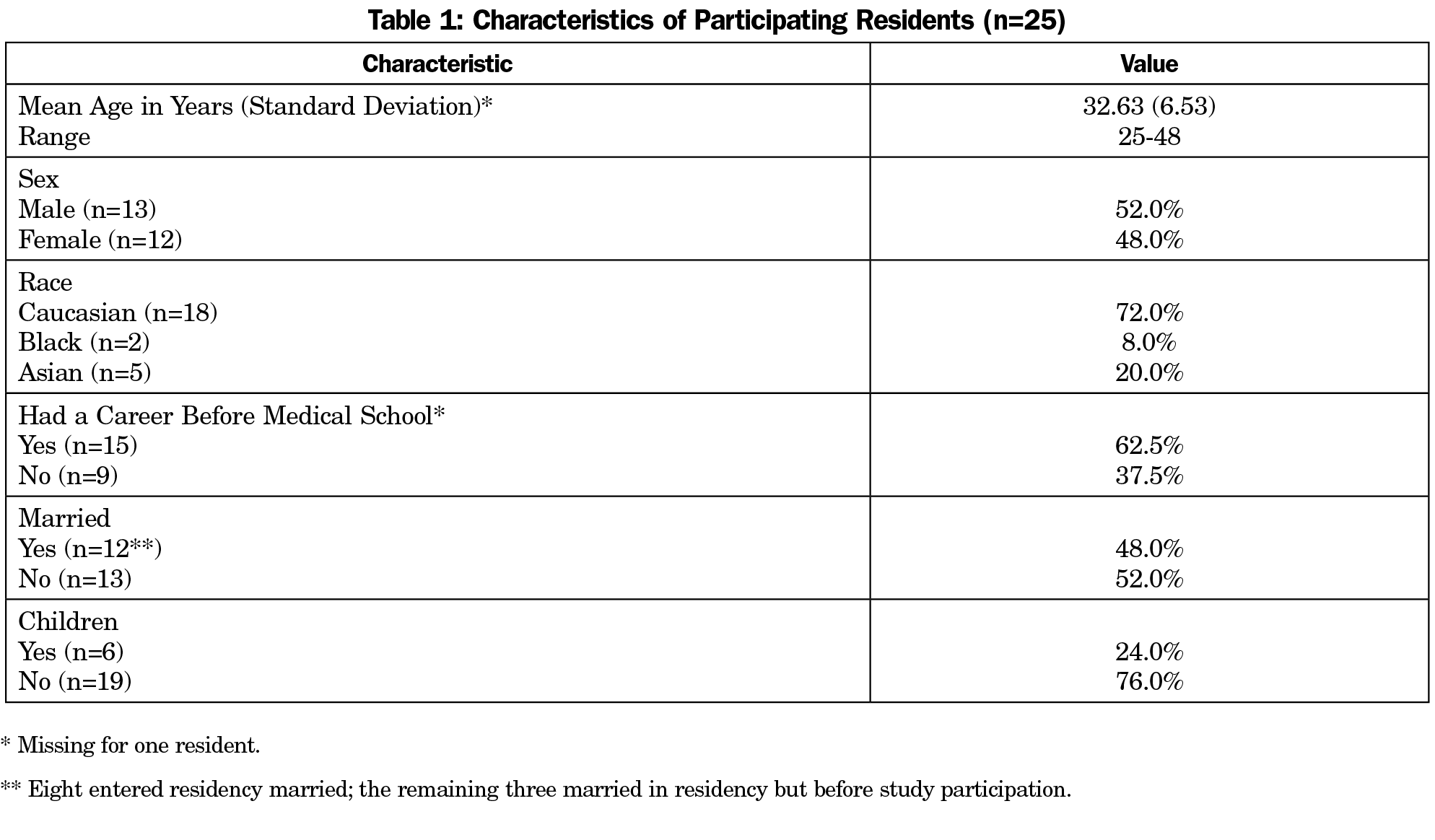

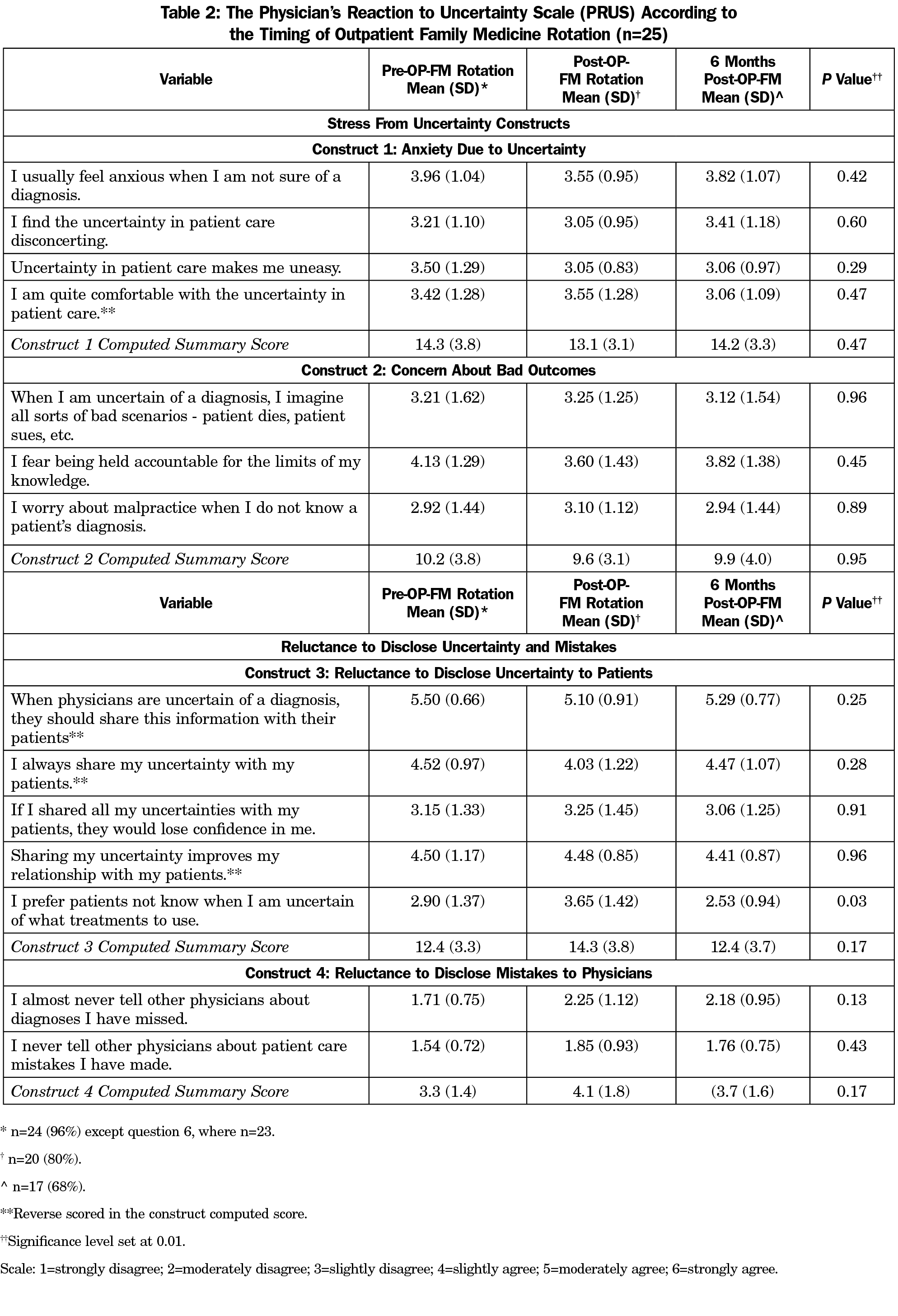

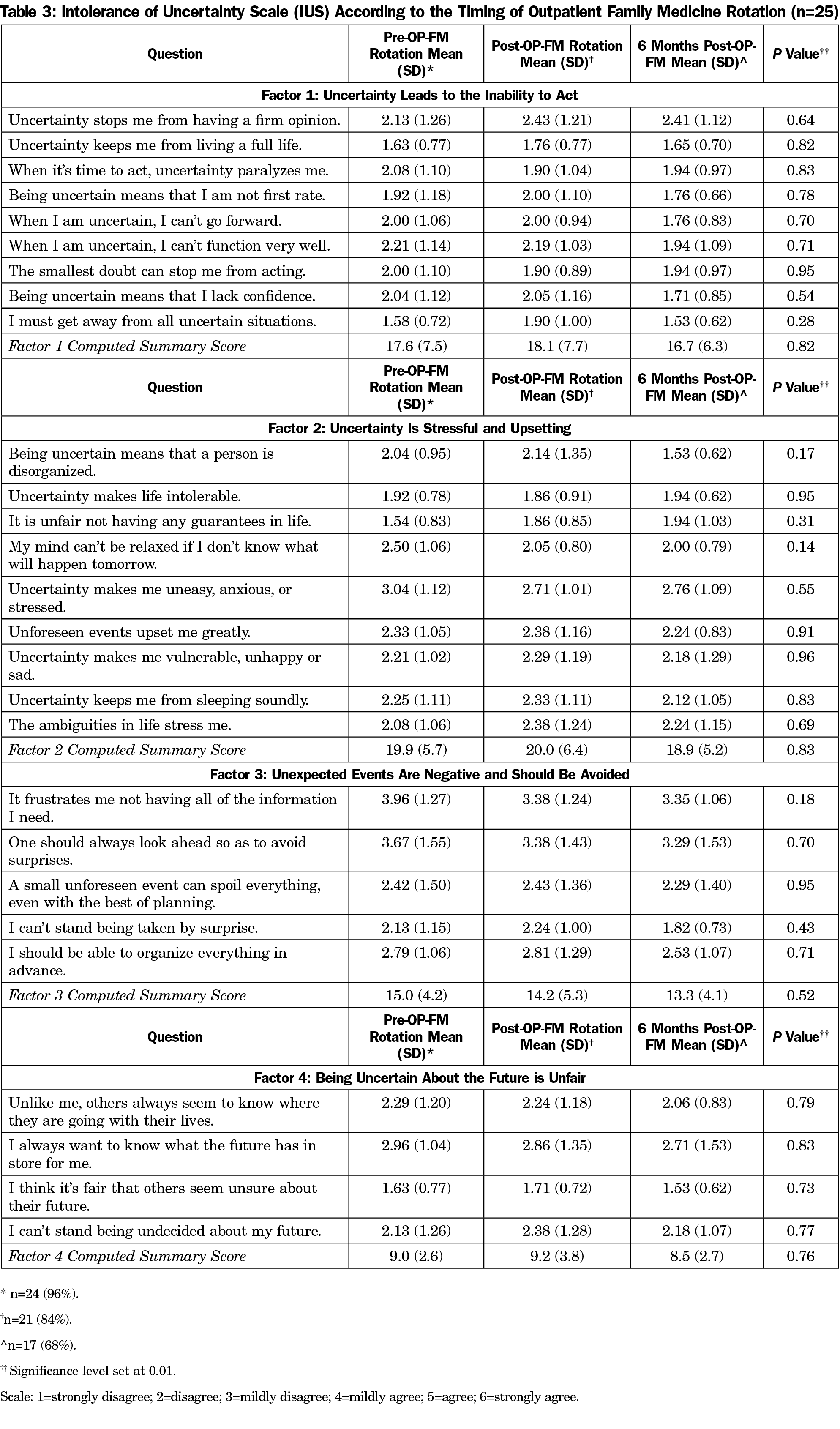

Response rates were 96% (24/25) prior to OPFM-T, 80% immediately following (20/25), and 68% (17/25) at 6 months post-OPFM-T. Participant age averaged 32.6 years (range: 25-48). Participants were predominantly male (52%) and Caucasian (72%; Table 1). One variable on the PRUS survey was borderline statistically different across the assessments related to OPFM-T rotations (Table 2): “I prefer patients not know when I am uncertain of what treatments to use” (2.9 prior to OPFM-T, 3.65 immediately post and 2.53 six-months post; P=.03). However, the computed construct score was not statistically different across the assessment periods. Individual variable and construct scores for the IUS survey (Table 3) showed no statistically significant changes pre- and postrotation.

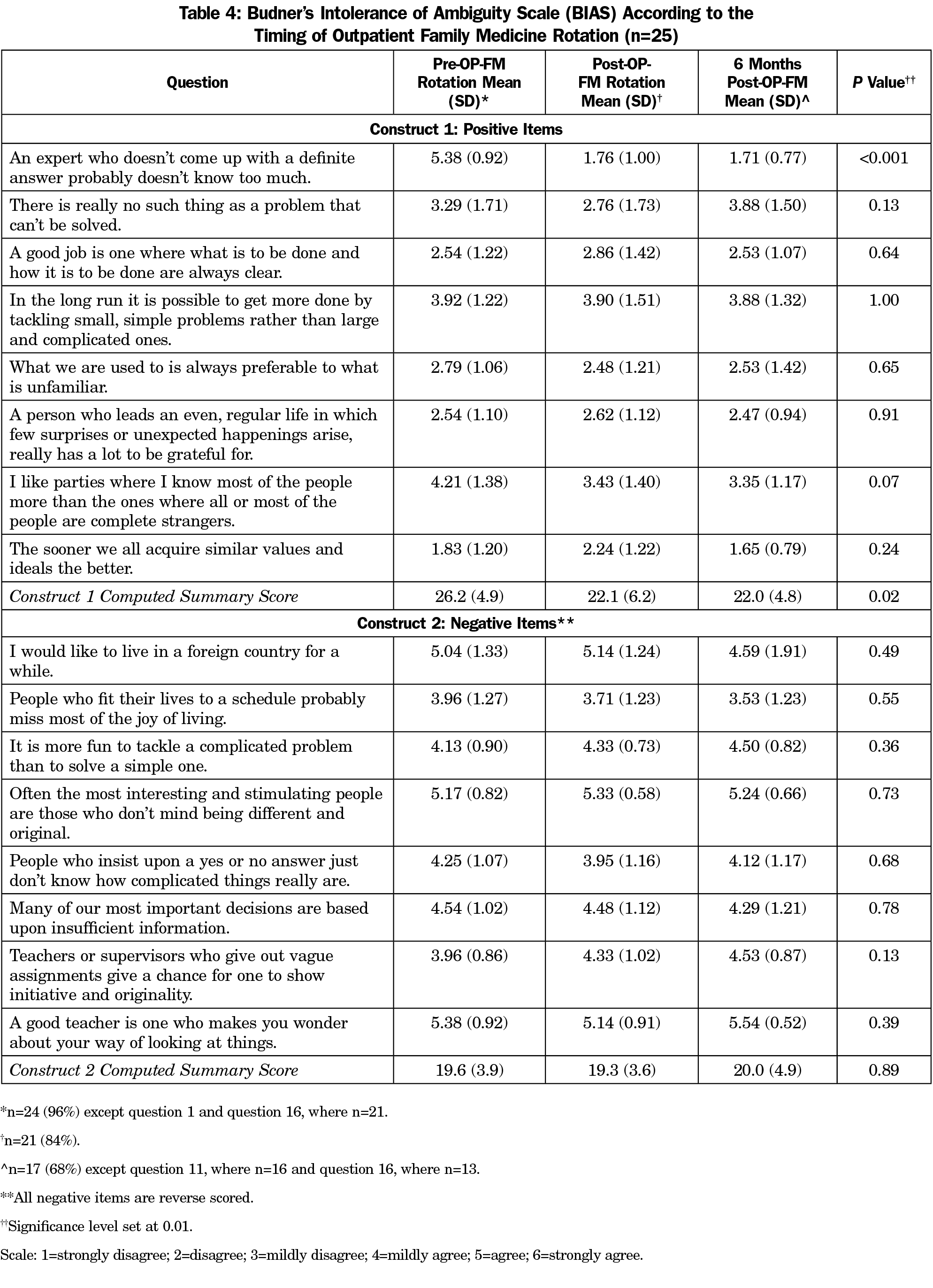

Table 4 shows one individual variable, and its corresponding construct score for the BIAS survey was statistically different according to timing of assessments. The variable, “An expert who doesn’t come up with a definite answer probably doesn’t know too much,” had a score of 5.38 prior to the rotation, which dropped to 1.76 immediately following it and remained the same (1.71) 6 months postrotation (P<0.001). In addition, Construct 1 (Positive Tolerance of Ambiguity) also showed borderline significant changes according to the timing of the OPFM-T with a score of 26.2 prior to the rotation, 22.1 immediately after the rotation, and 22.0 6 months after the rotation (P=0.02). Table 5 shows individual variable and construct scores for the CD-RISC survey were not statistically different pre- and postrotation.

We implemented this curriculum in response to residents’ reports that they felt outpatient care was difficult because of its ambiguity. We hypothesized that a more standardized ambulatory care curriculum designed to augment role modeling and enhancing knowledge, skills, and attitudes by our family medicine clinical preceptors would reduce this ambiguity. Our small exploratory study found that curriculum designed to improve tolerance of ambiguity influenced a single measurement construct within one of four scales we used to assess it: positive items in the BIAS survey.12,13 Budner defined intolerance of ambiguity as the tendency to perceive or interpret ambiguous situations as sources of threat,12 with higher scores indicating greater perceived threat than lower scores. We found this construct scored higher prior to undertaking the OPFM-T and it decreased statistically, even in our small sample of residents, after undertaking this curriculum, a result that did not change 6 months after completing it. This suggests the curriculum may have helped reduce perceptions of ambiguity as a threat.

There are several consequences of anxiety associated with clinical uncertainty, including the link between intolerance to ambiguity and burnout.15 Thus, increasing residents’ tolerance of uncertainty could help decrease burnout and its negative consequences. Many training programs are investing considerable time and energy to bolster resident resilience and decrease burnout with wellness programs.16-17 Intolerance of clinical uncertainty also has repercussions for clinical care, as studies show that as physician anxiety about unclear clinical situations increases diagnostic testing and costs of care.12,18 One estimate suggests that 17% of excessive medical costs arise from physician uncertainty about diagnosis.17 While written guidelines regarding physician/patient communication in the face of clinical uncertainty exist,21 physicians may be reluctant to disclose their uncertainty to patients due to assumptions about perceived lack of skill or knowledge.2 Other studies have unexpectedly shown that increased physician uncertainty led to improved patient satisfaction in shared decision-making models.14,19

Though we find the results of this study promising, there are some limitations. This study was conducted in a single program with only 25 residents in different stages of training. The sample was too small to stratify our results according to training stage. These issues limit the generalizability of our findings. We did not include a control group in this study. Thus, it is possible that our sustained differences may have resulted from additional family medicine residency training.

In conclusion, curriculum designed to improve tolerance to ambiguity appear to reduce the perceived threats of ambiguity in this small exploratory study. We plan to utilize a qualitative approach in our next study to discern some of the more nuanced changes in knowledge, skills and attitudes in response to the OPFM-T curricular innovation.

Acknowledgments

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: MedEdNet, based at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon supported this work.

References

- Biehn J. Managing uncertainty in family practice. Can Med Assoc J. 1982;126(8):915-917.

- Politi MC, Légaré F. Physicians’ reactions to uncertainty in the context of shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80(2):155-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.030.

- Katerndahl D, Wood R, Jaén CR. Family medicine outpatient encounters are more complex than those of cardiology and psychiatry. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(1):6-15. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2011.01.100057.

- Carney PA, Waller E, Eiff MP, et al. Measuring family physician identity: the development of a new instrument. Fam Med. 2013;45(10):708-718.

- DeForge BR, Sobal J. Intolerance of ambiguity among family practice residents. Fam Med. 1991;23(6):466-468.

- Yaphe J. Teaching and learning about uncertainty in family medicine. Rev Port Med Geral Fam. 2014;30:286-287.

- DeForge BR, Sobal J. Investigating whether medical students’ intolerance of ambiguity is associated with their specialty selections. Acad Med. 1991;66(1):49-51. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199101000-00015.

- Luther VP, Crandall SJ. Commentary: ambiguity and uncertainty: neglected elements of medical education curricula? Acad Med. 2011;86(7):799-800. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31821da915.

- Schneider A, Wübken M, Linde K, Bühner M. Communicating and dealing with uncertainty in general practice: the association with neuroticism. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e102780. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102780.

- Gerrity MS, White KP, deVellis RF, Dittus RS. Physicians´ reactions to uncertainty: refining the constructs and scales. Motiv Emot. 1995;19(3):175-191. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02250510.

- Carleton RN, Weeks JW, Howell AN, Asmundson GJG, Antony MM, McCabe RE. Assessing the latent structure of the intolerance of uncertainty construct: an initial taxometric analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26(1):150-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.10.006.

- Sobal J, DeForge BR. Reliability of Budner’s intolerance of ambiguity scale in medical students. Psychol Rep. 1992;71(1):15-18. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1992.71.1.15.

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-451. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134.

- Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76-82. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113.

- Ghosh AK. Understanding medical uncertainty: a primer for physicians. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:739-742.

- Politi MC, Clark MA, Ombao H, Légaré F. The impact of physicians’ reactions to uncertainty on patients’ decision satisfaction. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(4):575-578. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01520.x.

- Gerrity MS, White KP, DeVellis RF, Dittus RS. Physicians’ Reactions to Uncertainty: refining the constructs and scales. Motiv Emot. 1995;19(3):175-191. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02250510.

- Carleton RN, Norton MA, Asmundson GJG. Fearing the unknown: a short version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. J Anxiety Disord. 2007;21(1):105-117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.014.

- Budner S. Intolerance of ambiguity as a personality variable. J Pers. 1962;30(1):29-50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1962.tb02303.x.

Lead Author

Deborah Taylor, PhD

Affiliations: Central Maine Medical Center Family Medicine Residency Program, Lewiston, ME

Co-Authors

Bethany Picker, MD - Central Maine Medical Center Family Medicine Residency Program, Lewiston, ME

Donald Woolever, MD - Central Maine Medical Center Family Medicine Residency Program, Lewiston, ME

Erin K. Thayer, BA - Oregon Health and Science University, Department of Family Medicine, Portland, OR

Patricia A. Carney, PhD - Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR

Ari B. Galper, BA - Oregon Health and Science University, Department of Family Medicine, Portland, OR

Corresponding Author

Deborah Taylor, PhD

Correspondence: Central Maine Medical Center Family Medicine Residency, 76 High Street, Lewiston, ME 04240. 207-795-2819. Fax: 207-795-2190.

Email: taylord@cmhc.org

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.