Background and Objectives: Students on their family medicine clerkship at Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine get little clinical exposure to obstetric care, which is not commonly provided by family physicians in urban settings. To address this, we added to our clerkship didactic curriculum a 2-hour session involving a standardized patient (SP). The SP is collectively interviewed by the student group during four simulated prenatal visits, each of which present a different complication of pregnancy. The goal of this study was to evaluate the students’ perception of this session’s utility, the session’s ability to increase student self-confidence regarding obstetric issues, and perceived relevance of obstetrics to family medicine.

Methods: During the 2016-2017 academic year, we evaluated this educational intervention using anonymous, immediate postsession surveys containing both Likert scale and open-ended questions. Qualitative answers were analyzed using a thematic analysis approach, with development of a codebook by consensus.

Results: Students overwhelmingly found this session to be pertinent to their learning needs and reported an increase in their self-confidence level regarding obstetrical care. Continuity of care, comprehensive care, and an emphasis on health prevention were identified themes relating how obstetrics embodies the principles of family medicine.

Conclusions: We developed this prenatal standardized patient experience to expose our clerkship students to full-spectrum family medicine, including primary care obstetrics. Our data suggests that this session increased students’ self-confidence with obstetrics management, filled in gaps in their clinical exposure to full-spectrum family medicine, and addressed a perceived learning need.

National data demonstrates high utilization of the primary care setting for a diverse array of women’s sexual and reproductive health care needs, including antenatal, prenatal, and postpartum care.1,2 A 2002 study suggested that six percent of diagnoses encountered by medical students on their family medicine clerkship were related to women’s health concerns, including normal pregnancy.3 However, given the diversity of family medicine practice, there is likely high variability in these numbers.

For example, in the Southern United States, where the Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine is located, only eight percent of family physicians practice hospital obstetrics.2 While a higher percentage of family physicians may practice outpatient obstetrics, an evaluation of our 8-week family medicine clerkship revealed that 82% of students saw no patients for prenatal care during their rotation and that no students saw more than four pregnant patients.

This significantly inadequate exposure to obstetrics made it difficult for our students to meet the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine National Clerkship Curriculum’s specific objectives related to obstetric care.5 We aimed to fill this educational gap by using a standardized patient scenario to create a simulated learning experience for all students outside of the clinical setting. The purpose of this study was to use qualitative and quantitative methods to evaluate students’ perceptions of this session’s utility and relevance to family medicine, and their self-confidence in management of obstetric issues.

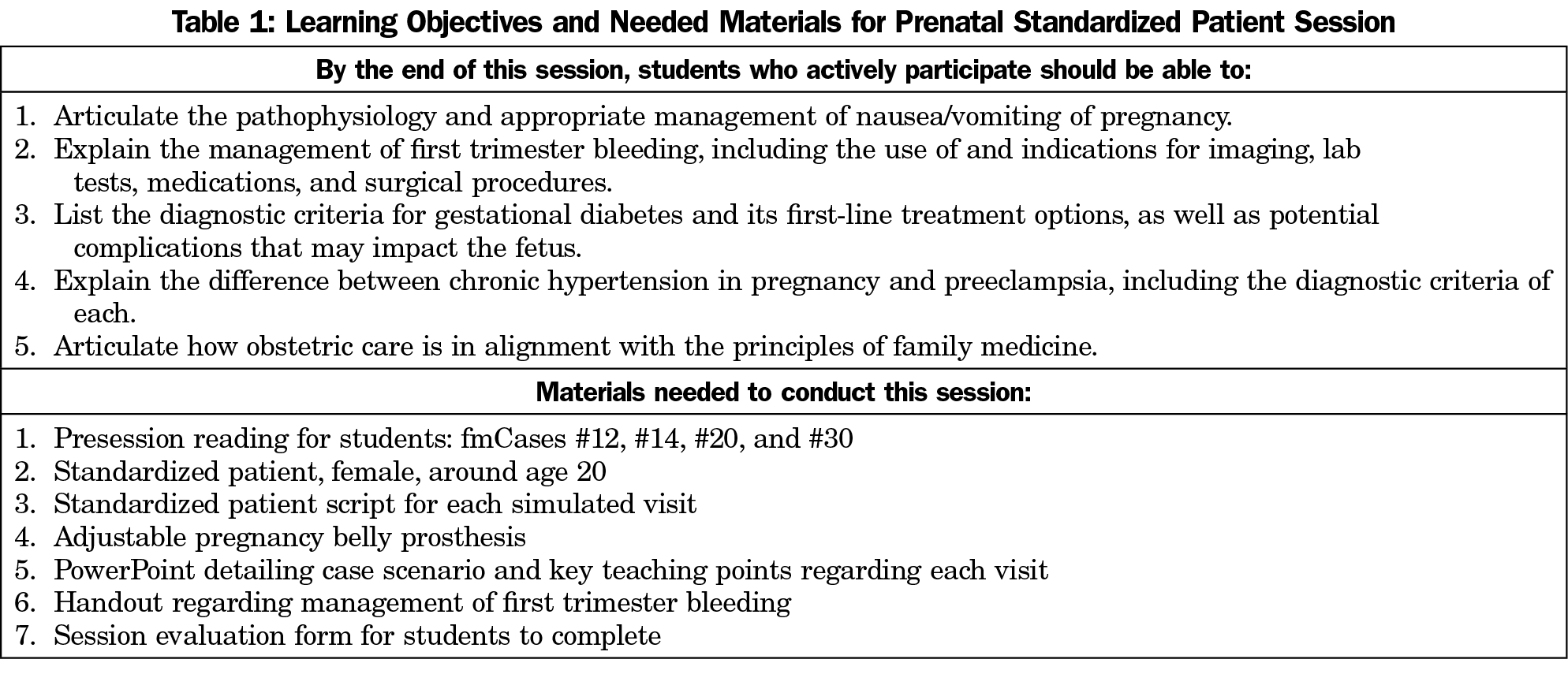

To increase our students’ exposure to primary care obstetrics, we developed a 2-hour standardized patient session, which was given a total of six times during the 2016-2017 academic year. During this session, a group of 20 students collectively interviewed a standardized patient at four visits throughout the course of her simulated pregnancy. After each simulated encounter, a PowerPoint presentation reviewed the symptoms, diagnosis, and management of each visit’s chief concern. Table 1 details the learning objectives for each simulated encounter.

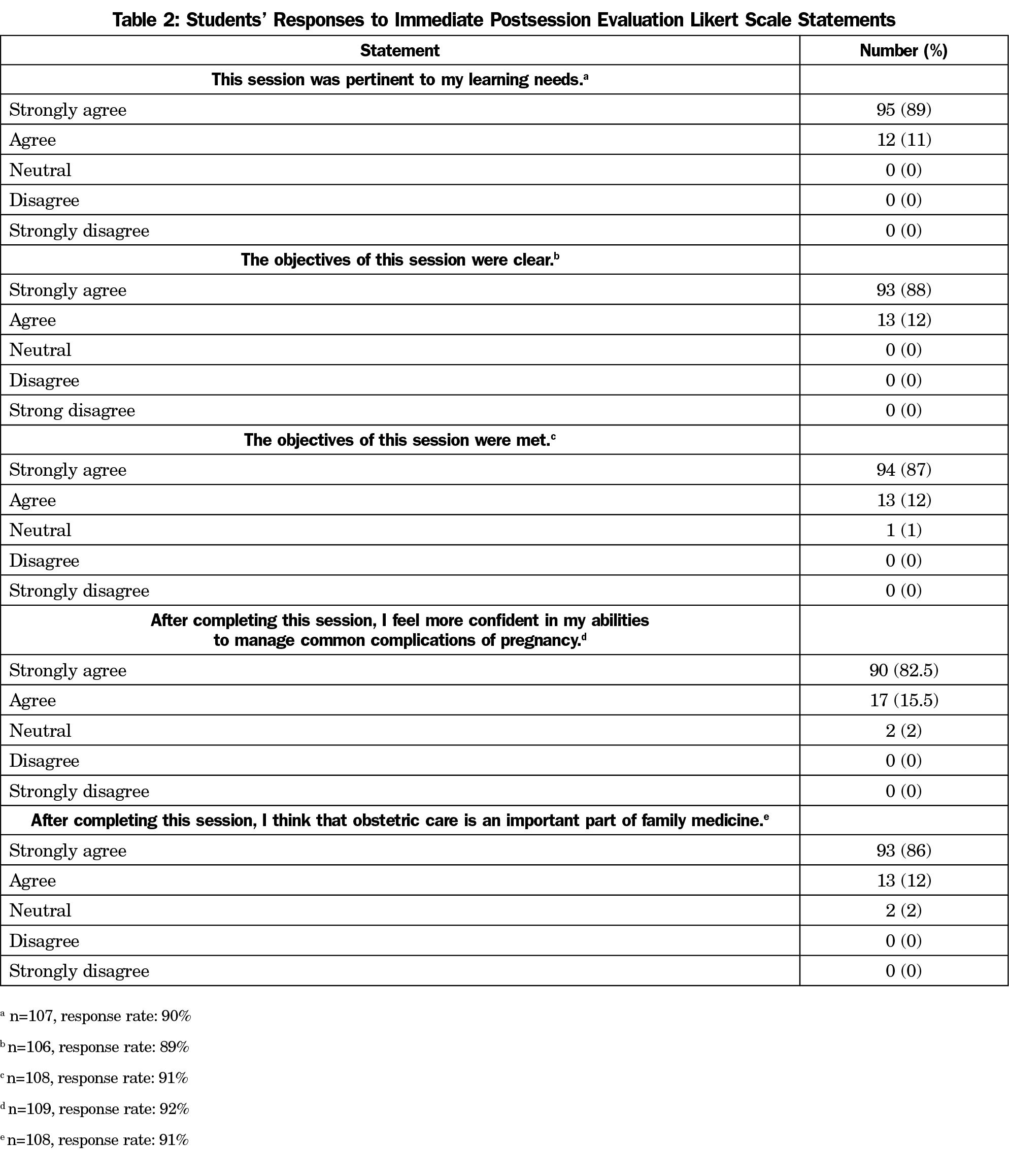

All family medicine clerkship students participated in this session. An immediate, paper-based, postsession, untimed evaluation was administered to all 119 members of class of 2018 at our institution. The evaluation included five Likert-scale questions and one open-ended question, shown in Tables 2 and 3. As completing the evaluation in its entirety or in part was not required, we received a variable number of responses to each question. Specific response rates can be found in Tables 2 and 3.

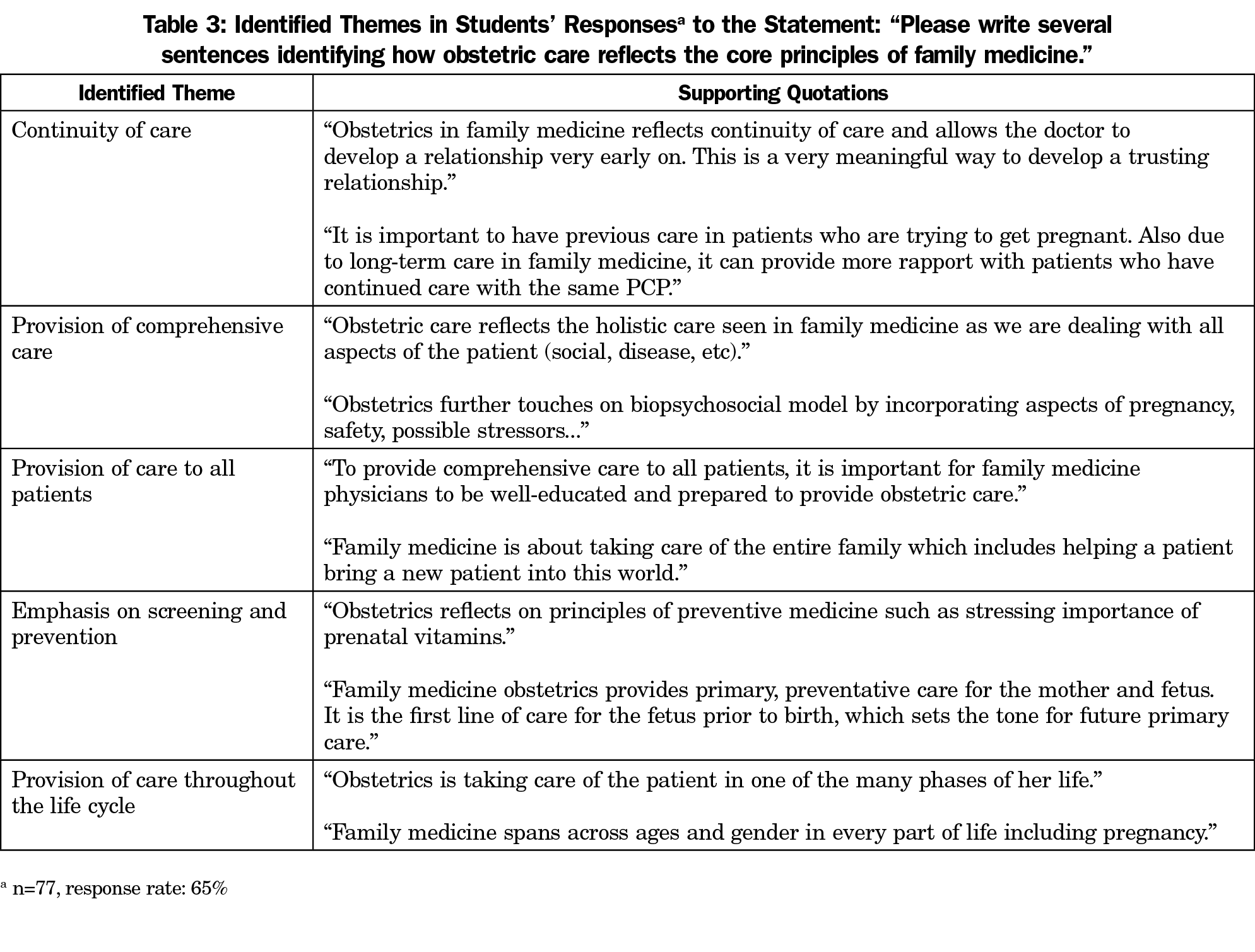

A thematic analysis approach6 was used to analyze students’ qualitative answers. In this inductive process, two coders identified the common themes in students’ answers, and then met to develop a consensus of themes. Institutional review board exemption from Florida International University was obtained.

Students had an overwhelmingly positive response to this session. In particular, all students either agreed or strongly agreed that this session was pertinent to their learning needs. Furthermore, 98% of students felt that this session had increased their confidence in managing common complications of pregnancy. Table 2 reports student responses to the Likert scale questions in our session evaluation. Students articulated how obstetrics embodies the principles of family medicine. Identified themes in their responses, with supporting quotes, can be found in Table 3.

We also aimed to evaluate any change in obstetrics knowledge following the implementation of our intervention. All students on our clerkship are required to take the family medicine National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) shelf exam; so to evaluate change in knowledge, we identified the obstetrics questions on the NBME shelf exams for the class of 2017 (the control group), and class of 2018 (the intervention group). Student performance on these questions was compared between the two class years. There was no statistically significant difference between the performance of the class of 2017 and class of 2018 on the 14 identified questions during each academic year.

This curricular evaluation suggests that in the absence of clinical exposure to prenatal care, a standardized patient group experience may provide a viable educational experience for students on their family medicine clerkship. In addition to increasing self-confidence and knowledge, this session also showed the important role that a family medicine approach—given its focus on screening and prevention, continuity of care, and comprehensiveness—can play in obstetric care.

While our analysis of student performance on obstetrics-related questions on the family medicine NBME shelf exam did not support postintervention improvement, this data was based on a total of only 14 obstetrics-related questions across the entire academic year. Additionally, average performance on these questions also declined nationally over the same time period. A more comprehensive pre- and posttest specifically targeted to the session material might provide more meaningful data.

Limitations to this study include that the postsession survey was given out and collected by the course coordinator which, even though no identifying information was collected, may have resulted in students providing a positive evaluation due to perceived concerns regarding anonymity. Additionally, students who felt that the session was beneficial may have disproportionately self-selected to complete the evaluation. Finally, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to evaluate the long-term impact of this curricular intervention.

There is some research to support the integration of standardized patient simulation into family medicine clerkships as a way to support education regarding continuity of care, which is often difficult to recreate in clinical courses that are only several weeks in length.7 However, one-on-one objective structured clinical exam encounters require significant resources, including faculty time and departmental financial investment to pay standardized patients. Our standardized patient experience is less resource intensive in that it requires only one faculty member and one standardized patient. Additionally, it provides the ability to integrate didactic teaching with the simulated patient encounter, thereby providing a framework to contextualize medical knowledge in the setting of a simulated clinical encounter. This format should be easily adaptable to other medical issues that are not frequently seen by students in the clinical setting at a given institution, or for clerkships wishing to enhance their teaching regarding longitudinal care.

For the class of 2019, this session remains unchanged. However, students are now additionally exposed to the same standardized patient for two more interactive sessions during our clerkship, including a preventive health visit before the patient’s pregnancy and a combined postpartum/newborn visit. Future areas of curricular research include investigating the impact of the integration of this longitudinal curriculum on students’ perception of primary care obstetrics.

Acknowledgments

Presented at the 2017 STFM Conference on Medical Student Education, Anaheim, CA, February 9-12, 2017.

References

- Cohen D, Coco A. Trends in the provision of preventive women’s health services by family physicians. Fam Med. 2011;43(3):166-171.

- Kozhimannil KB, Fontaine P. Care from family physicians reported by pregnant women in the United States. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(4):350-354. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1510.

- O’Hara BS, Saywell RM Jr, Zollinger TW, et al. Students’ experience with women’s health care in a family medicine clerkship. Med Educ. 2002;36(5):456-465. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01165.x.

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. National Clerkship Curriculum. http://www.stfm.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=upiiuNFp3Vc%3d&tabid=17603&portalid=49. January 8, 2017.

- Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):80-92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107.

- Vest BM, Lynch A, McGuigan D, Servoss T, Zinnerstrom K, Symons AB. Using standardized patient encounters to teach longitudinal continuity of care in a family medicine clerkship. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):208. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0733-y.

There are no comments for this article.