Burnout in medical settings is a well-known phenomenon,1 and improving the work-life balance of providers is said to be the fourth proposed aim of health care.2 Between 25% and 60% of physicians in the United States experience a high degree of burnout at some point in their career.3,4 These traits often produce negative consequences, including decreased work productivity, personal health issues, and a lack of collaboration with colleagues.5-7 To curb these rising trends, administrators and clinical directors alike are attempting to find solutions to reduce workload and additional responsibilities of physicians in their routine practice. More recently, integrated care has been seen to help physicians offer more comprehensive services to patients and families. Providers are able to collaborate on cases and coordinate treatment plans in a routine fashion.8,9 It is unknown, however, whether integrated care teams actually serve as a buffer to the risks of burnout in physicians. In this study, we explored whether higher levels of integrated care practice are associated with lower rates of burnout and depersonalization of primary care physicians.

BRIEF REPORTS

Associations Between Integrated Care Practice and Burnout Factors of Primary Care Physicians

Max Zubatsky, PhD | Doug Pettinelli, PhD | Joanne Salas, MPH | Dawn Davis, MD

Fam Med. 2018;50(10):770-774.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2018.655711

Background and Objectives: Physician burnout is increasingly problematic across many health care settings. Despite this trend, little is known about whether the type of collaboration in these settings may potentially help curb this trend. We explored whether higher levels of integrated care practice are associated with reduced burnout for physicians across settings.

Methods: A national survey was sent to health care professionals who work in a variety of medical settings. Primary care physicians (n=288) were a subset of this sample and were asked about their practice demographics and perceptions of burnout. A shortened version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) assessed for areas of burnout in physicians.

Results: Higher levels of integrated care were associated with higher personal accomplishment (B=1.89, 95% CI:0.47, 3.31) and lower depersonalization (B=-2.48, 95% CI:-4.54, -0.42) in routine practice on the MBI. No significant associations were found between MBI scores and both years of practice at a current site or number of providers at the site.

Conclusions: While physician burnout continues to be a worsening problem, integrated care may be an additional strategy to help curb this trend. Administrators need to consider the value of integrated practice in addressing physician wellness—the potentially next big aim of health care.

A cross-sectional design asked health care providers to complete a one-time online survey from May to August of 2017. Providers must have been currently providing care to patients and/or families in a medical setting. Purposeful sampling was performed, where participants were recruited from a number of organizations and listservs in the United States, including the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine, the Collaborative Family Healthcare Association, the General Services Administration, the American Psychological Association, the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy, and the American Pharmacy Directors Association. This national survey was sent to a number of different health care professionals, mainly primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, behavioral health providers, case managers, psychiatrists, and pharmacists. Additionally, family medicine, psychiatry, and pharmacy residencies in all 50 states were contacted for snowball recruitment. Participants were asked to refer the survey to any potential professionals who operate in any level of integrated care practice.

A total of 804 participants entered the study, with 736 completing all sections of the study survey for a 91.5% completion rate. Primary care physicians (n=288) completed 20 questions regarding demographic information, practice-related questions, professional burnout questions, and an open-ended qualitative question. A modified version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) for Health and Human Service Providers10 was used to capture emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and personal accomplishment (PA). Three questions per scale were measured on a 0 to 6 scale (never-everyday); thus, scores ranged from 0 to 18.

For this study, integrated care practice was defined by the principles established of the six levels of integrated care, developed by Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) and Health Resources and Services Administration.11 We chose this definition of integrated care because it highlights specific skills that both providers and clinics need to operate under. We grouped level of care into a three-tiered model based on SAMSHA guidelines: minimal collaboration (levels 1 and 2), colocated (levels 3 and 4), and full integration (levels 5 and 6).

Analytic Plan

Characteristics of physicians were summarized with means and frequencies. Associations between degree of integrated care practice and each MBI scale were assessed using multiple linear regression models, controlling for demographic and practice characteristics. Equations calculated unstandardized betas (B) and 95% confidence intervals.

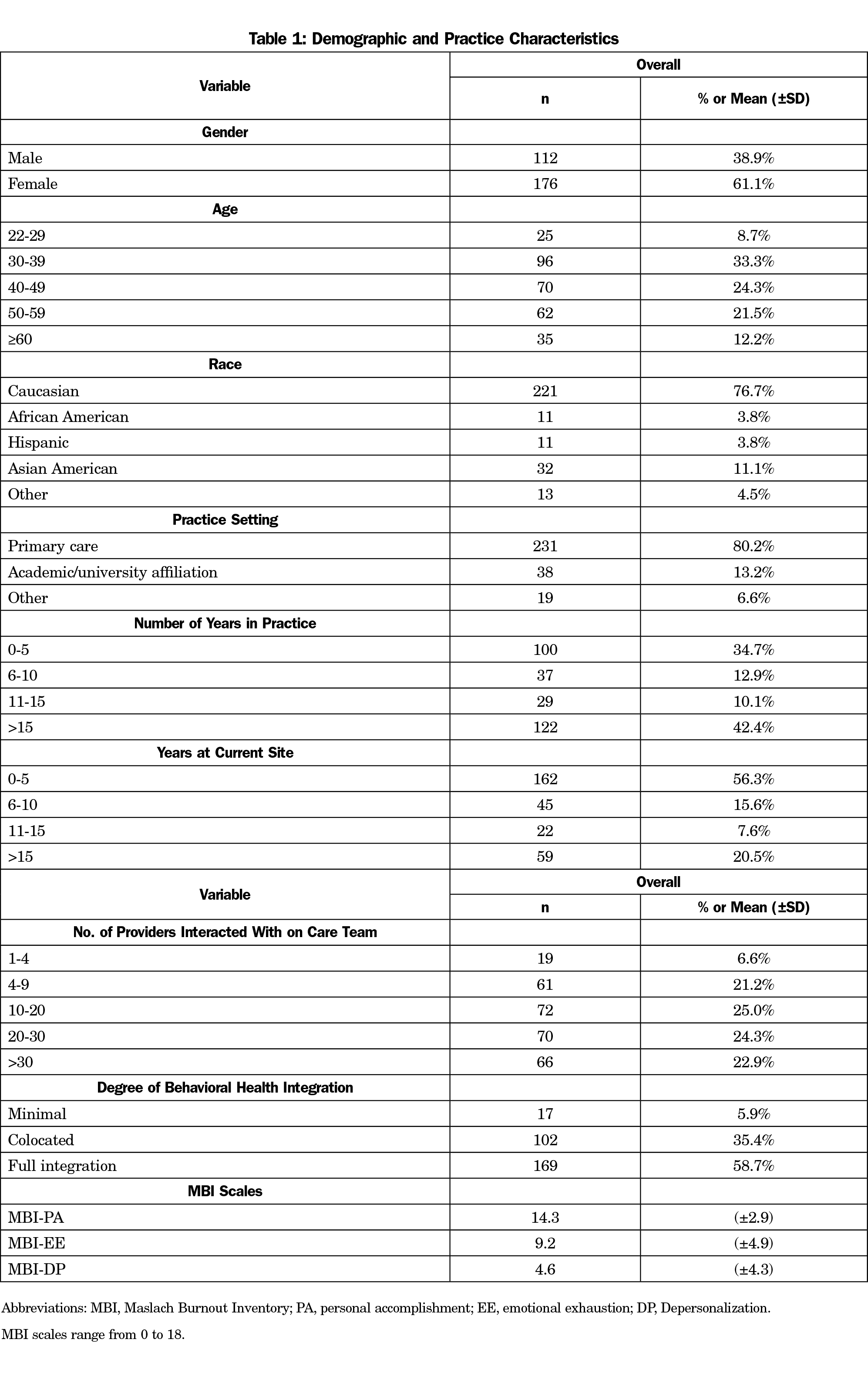

The study sample (Table 1) was largely primary care physicians between 30 and 59 years old (79.1%), practicing in a primary care settings (80.2%), and having practiced at their current site for less than 10 years (71.9%). The majority of physicians in this study (94.1%) reported working in either a colocated or fully-integrated practice setting. Regarding the MBI scales, PCPs overall had high perceived personal accomplishment, moderate levels of emotional exhaustion, and low depersonalization.

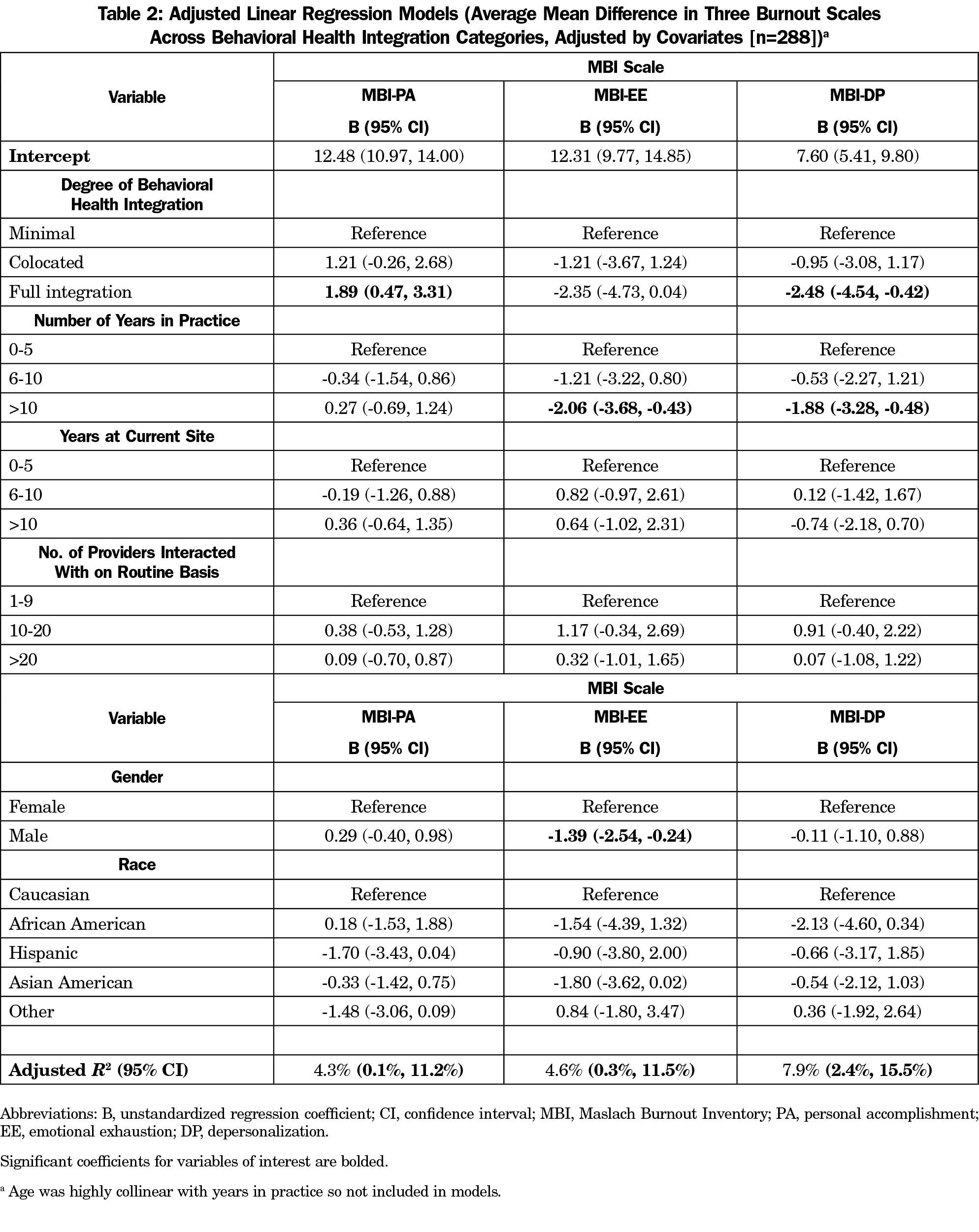

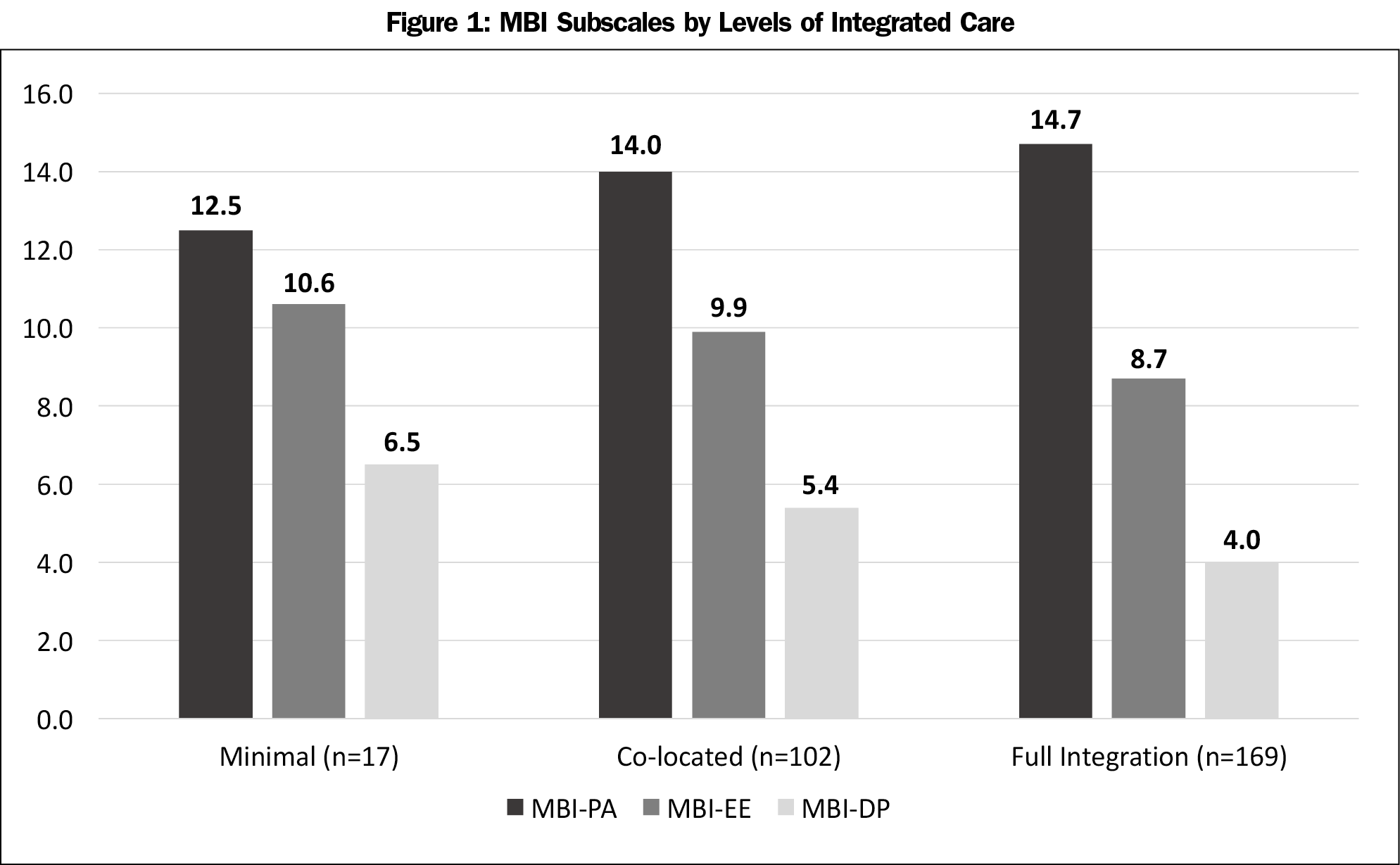

Table 2 shows that physicians who work in fully-integrated care settings report higher levels of personal accomplishment (B=1.89; 95% CI=0.47, 3.31) and lower levels of depersonalization (B=-2.48; 95% CI=-4.54, -0.42) when compared to physicians in minimal collaboration settings. Males reported lower levels of emotional exhaustion, and years in practice was negatively associated with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. Figure 1 highlights the overall differences in the three MBI scores across three categories of integrated care settings.

Overall, we found significant differences in personal accomplishment and depersonalization, but not emotional exhaustion, across three categories of integrated care practice. There were no differences found on the MBI regarding number of providers who work with physicians at their site, years at current site, or race. Adjusted R2 values were low, indicating a high proportion of unexplained variance due to unmeasured factors. However, collaborative care practice may provide some benefit in the prevention of burnout and burden. The associations found in this study confirm the literature on the value of integrated care beyond just patient outcomes and quality of health care delivery.4,9 Higher levels of coordination and team-based care between physicians and behavioral health providers not only help to foster effective collaboration, but can also impact patient outcomes and cost effetiveness.12-14

There are some limitations to note. This study was cross sectional and did not track burnout rates across several years for PCPs. Results might reflect situational burnout to a particular time of rotation in physicians’ jobs. Additionally, the use of listservs and organizations for recruitment limited our ability to calculate an accurate response rate from these sources. Providers who felt they were experiencing burnout and compassion fatigue may have been more inclined to complete the survey. Snowball sampling was a nonprobability sampling technique, making it difficult to determine any sampling error in the study. Finally, as the survey was intended for practicing providers, a modified version of the full MBI was administered to assess for burnout characteristics. The results may not have fully reflected the breadth of burnout factors that providers face in different care settings. The shortened version of the MBI may have jeopardized the validity of the three scales and may not fully capture all of the burnout factors related to patient care.

While administrators continue to find ways to improve the work-life balance of physicians, team-based care may be one way to reduce personal and professional burnout. In addition to medical schools and residencies improving integrated care competencies of new physicians, primary care as a whole may need to develop more resiliency strategies for current physicians who suffer from extreme burnout in practice. Improving the care coordination among clinics might be a useful first step to help improve the work-life balance for primary care physicians in the current health care climate.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank STFM, AAFP, and program directors of family medicine departments in all 50 states for support in recruitment.

References

- Rabatin J, Williams E, Baier Manwell L, Schwartz MD, Brown RL, Linzer M. Predictors and outcomes of burnout in primary care physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(1):41-43. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150131915607799

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-576. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1713

- Gregory ST, Menser T. Burnout among primary care physicians: A test of the areas of worklife model. J Healthc Manag. 2015;60(2):133-148. https://doi.org/10.1097/00115514-201503000-00009

- Helfrich CD, Dolan ED, Simonetti J, et al. Elements of team-based care in a patient-centered medical home are associated with lower burnout among VA primary care employees. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2)(suppl 2):S659-S666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2702-z

- Schaufeli WB, Maassen GH, Bakker AB, Sixma HJ. Stability and change in burnout: A 10‐year follow‐up study among primary care physicians. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2011;84(2):248-267. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02013.x

- Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199

- Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. Lancet. 2009;374(9702):1714-1721. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61424-0

- Sikka R, Morath JM, Leape L. The Quadruple Aim: care, health, cost and meaning in work. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(10):608-610. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004160

- Durbin A, Durbin J, Hensel JM, Deber R. Barriers and enablers to integrating mental health into primary care: a policy analysis. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2016;43(1):127-139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-013-9359-6

- Maslach C, Leiter MP. Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93(3):498-512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.498

- Heath B, Wise Romero P, Reynolds K. A Review and Proposed Standard Framework for Levels of Integrated Healthcare. Washington, DC: SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions; March 2013.

- Balasubramanian BA, Cohen DJ, Jetelina KK, et al. Outcomes of integrated behavioral health with primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(2):130-139. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2017.02.160234

- Green LA, Cifuentes M. Advancing care together by integrating primary care and behavioral health. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(suppl 1):S1-S6. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2015.S1.150102

- Gunn R, Davis MM, Hall J, et al. Designing clinical space for the delivery of integrated behavioral health and primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(suppl 1):S52-S62. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2015.S1.150053

Lead Author

Max Zubatsky, PhD

Affiliations: Department of Family and Community Medicine, Saint Louis University, St Louis, MO

Co-Authors

Doug Pettinelli, PhD - Department of Family and Community Medicine, Saint Louis University, St Louis, MO

Joanne Salas, MPH - Saint Louis University Department of Family and Community Medicine, St Louis, MO.

Dawn Davis, MD - Department of Family and Community Medicine, Saint Louis University, St Louis, MO

Corresponding Author

Max Zubatsky, PhD

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.