Maternity care access in the United States is in crisis. The American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology projects that by 2030 there will be a nationwide shortage of 9,000 obstetrician-gynecologists (OB/GYNs). Midwives and OB/GYNs have been called upon to address this crisis, yet in underserved areas, family physicians are often providing a majority of this care. Family medicine maternity care, a natural fit for the discipline, has been on sharp decline in recent years for many reasons including difficulties cultivating interdisciplinary relationships, navigating privileging, developing and maintaining adequate volume/competency, and preventing burnout. In 2016 and 2017, workshops were held among family medicine educators with resultant recommendations for essential strategies to support family physician maternity care providers. This article summarizes these strategies, provides guidance, and highlights the role family physicians have in addressing maternity care access for the underserved as well as presenting innovative ideas to train and retain rural family physician maternity care providers.

Since its inception in 1969, family medicine (FM) training in the United States has always included maternity care. Family physicians (FPs) who choose to provide maternity care in their practices are rewarded with a family-centered care model, offering continuity of care to women and their families before, during, and after the birth of their children. In many places, particularly in rural and urban underserved areas, FPs provide primary care for patients with chronic diseases, substance use, mental health issues, and interpersonal violence, and are exceptionally well suited to provide these services to the mother-child dyad. The unique FM approach to care of patients, families, and communities offers a comprehensive alternative to the care provided by midwives or obstetrician-gynecologists (OB/GYNs).

The American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) projects that by 2030 there will be a nationwide shortage of 9,000 OB/GYNs.1 Additionally, there has been a trend of OB/GYNs moving to predominantly urban or less impoverished settings in the last decade.2 Many recent articles cite a need to strengthen the certified nurse midwife (CNM) workforce through collaboration between ACOG and the Association of Certified Nurse Midwives (ACNM), but little is mentioned about the role of FPs in filling these gaps.1,34 Despite the ongoing need for maternity care providers, the percentage of FP maternity care providers continues to decline in the United States and Canada.5-10 A recent review of American Board of Family Medicine Examination questionnaires (for which response is mandatory for registrants) from 2003 to 2016 indicated a decline in FPs providing low volume of obstetrics services from 10% to 5% percent. The number of FPs providing high-volume obstetrics services remained steady until 2009, but declined by 50% from 2% to 1% after 2009.11 There is also a trend in declining numbers of FPs caring for children and women in general.12

Despite these trends, FPs often still provide the majority of maternity care in rural areas of the US.13 The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and ACOG both acknowledge that FPs sometimes provide all of the obstetric care in rural communities. The ACOG encourages OB/GYNs to partner with FPs to ensure adequate training and consultation in rural areas.14 The AAFP has similarly stated it will assist FPs who have training and demonstrated competency in obtaining and maintaining privileges in maternal/child care.15 Without the FP workforce, the loss of access to maternity services in these economically disadvantaged communities will likely widen the health disparities in the United States.

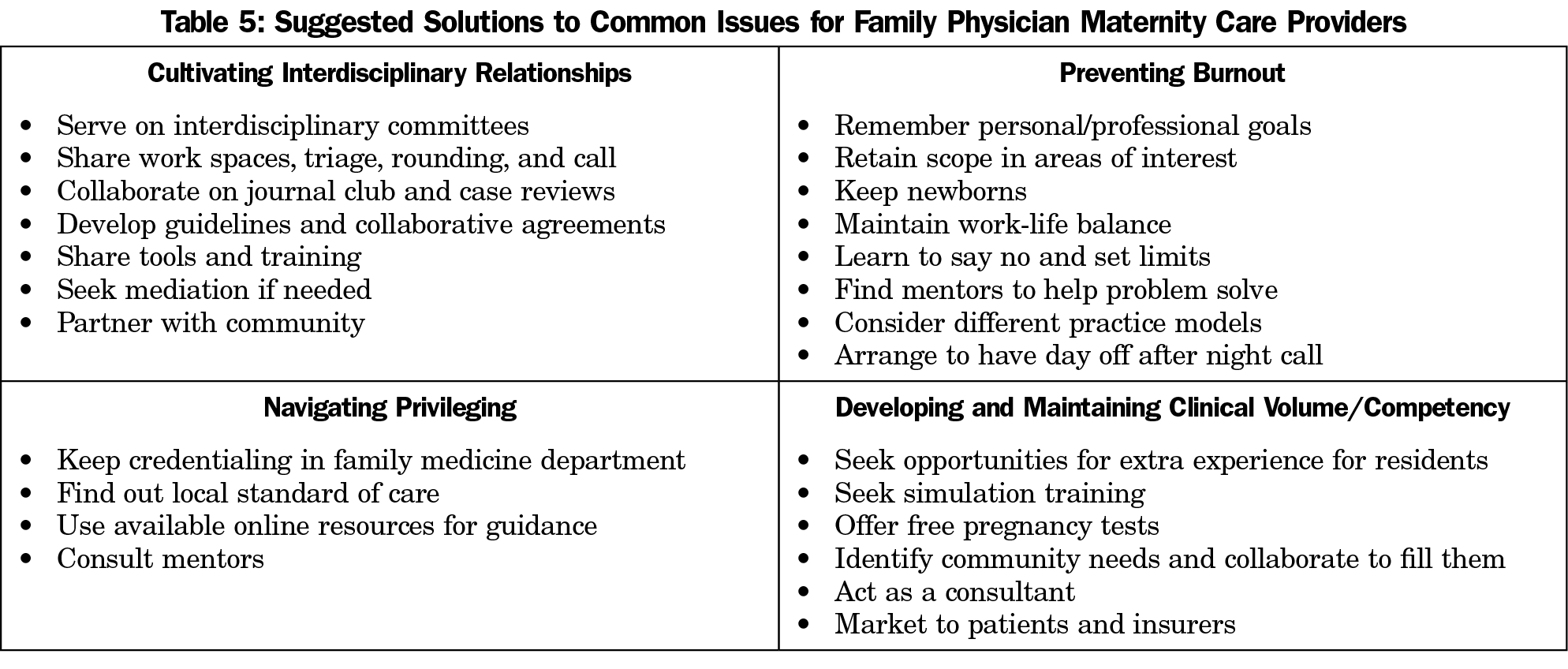

Supporting FP maternity care providers aligns with the goals of both professional organizations and of FM as a comprehensive specialty that strives to meet individual community needs. In 2016 and 2017 workshops were held at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) Annual Spring Conference to identify barriers for FP maternity care providers and share best practices. Drawing from these workshop discussions, this article describes strategies to overcome these challenges by cultivating interdisciplinary relationships, navigating privileging, developing and maintaining clinical volume/competency, and preventing burnout, as well as addressing the unique considerations for rural FPs.

Workshops at the STFM Annual Spring Conference in 2016 and 2017 involved medical students, FM residents, and practicing FPs discussing barriers to providing maternity care and sharing best practices in addressing these challenges. The 2016 preconference workshop, “Optimizing Interdisciplinary Maternity Care in FM Residencies: Expanding Your Teaching Toolkit,” included over 30 participants affiliated with FM residency programs in 15 states, the majority of whom were residency faculty. The goal of the workshop was to showcase best practices in innovative FM maternity care curricula at FM residency programs. The workshop focused on how interdisciplinary collaboration can address maternity care challenges such as skyrocketing intervention rates, persistent health disparities, and maintaining competency and engagement with maternity care among FM residents and faculty. There were 20 presenters, primarily FP faculty (but also one OB/GYN, two CNMs, and one RN), affiliated with Boston University, Medical College of Wisconsin, University of California at Davis, University of California at San Francisco, University of Massachusetts, University of North Carolina, and University of Wisconsin. Four breakout sessions included discussions about collaborating with obstetric, pediatric, and nursing departments; bolstering outpatient maternity care to address disparities and improve access to care; teaching about normal birth; and common issues for maternity care training (addressing privileging, volume, and competency).

At the 2017 STFM Annual Spring Conference, based on the challenges identified at the 2016 preconference, another 1-hour seminar entitled “Sticking With It: Mentoring Maternal Child Health Providers for the Long Haul” drew approximately 40 participants. Six FP facilitators chose preselected topics as a framework for discussion in the seminar; these included maintenance of volume, interdisciplinary relationships, privileging, and other barriers (which included maintaining interest and dealing with burnout and financial issues). Participants discussed potential solutions, shared resources such as local hospitals’ privileging documents, highlighted concerns about retraining pathways after time away from maternity care practice, and linked up to support one another through mentor and mentee relationships. Participants also reviewed the important role of FPs in addressing preconception care, rural and racial disparities, and public health and community collaboration.

Cultivating Interdisciplinary Relationships

The STFM workshop attendees identified instances of conflictual or obstructive relationships between FPs and specialist physicians in maternity care who often do not have a full understanding of FM training or skills. Participants recommended collaboration through interdisciplinary relationships as a key component in FM maternity care practice as a way of developing respect and trust between providers.16 These relationships include, but are not limited to, relationships with labor and postpartum nurses, midwives, OB/GYNs, pediatric clinicians, anesthesiology clinicians, social workers, researchers, and policy makers in community health.

Workshop participants recommended that FPs work to improve these relationships by fulfilling local clinical needs in critical patient care arenas. Many hospitals employ OB/GYNs as laborists for varying degrees of labor unit coverage, but also hire CNMs, physician assistants or nurse practitioners to staff labor/triage units, provide circumcision services, round on newborns, or provide other aspects of maternity and newborn care. FPs can easily fill many of these roles. By offering to help fill long- or short-term gaps in provider coverage, FPs can weave themselves into the permanent fabric of a maternal-child health unit. FPs can also build interdisciplinary relationships by leading or teaching in specific maternity or team-building courses as detailed in Table 1.17-25, 59

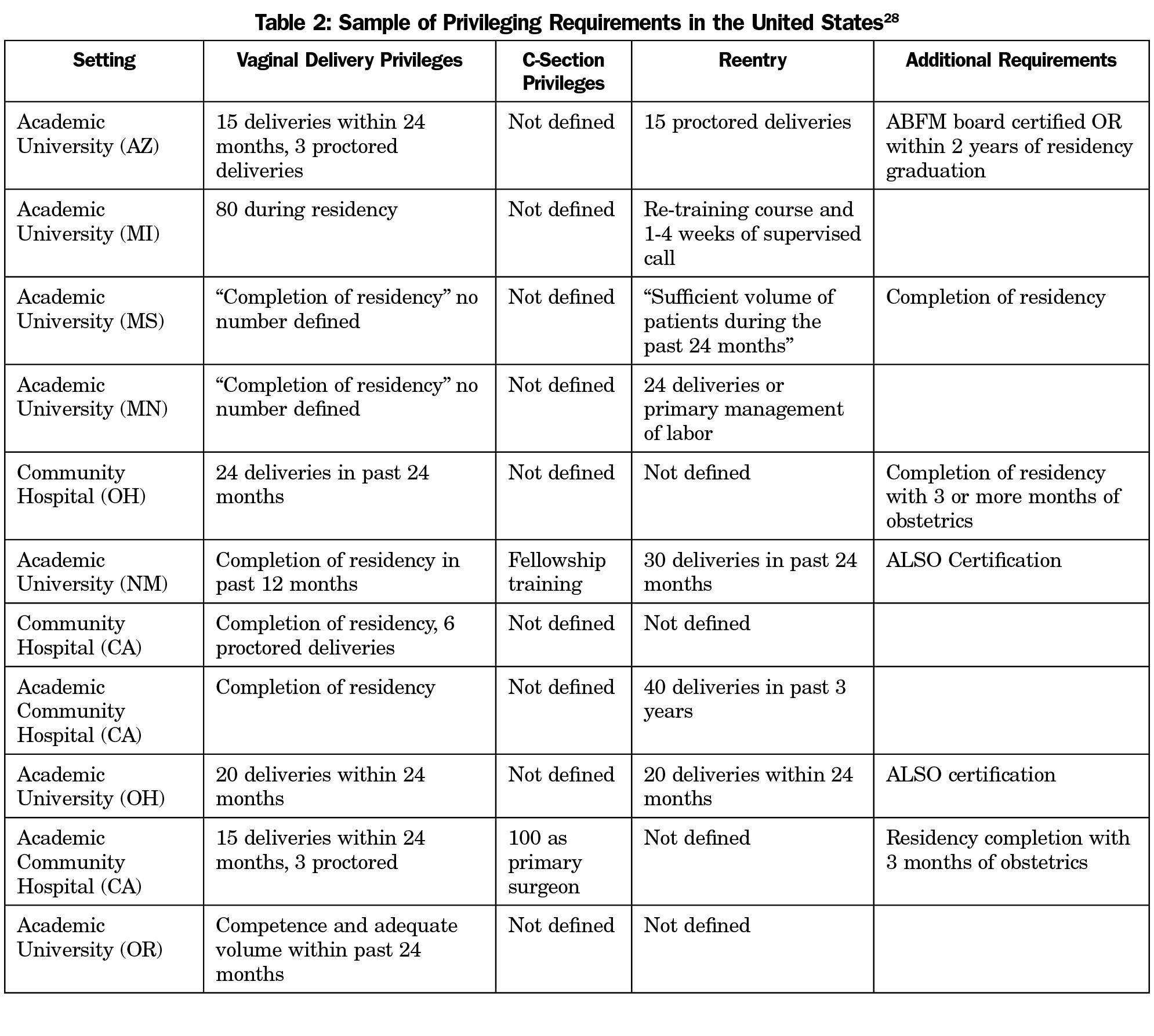

Another recurring theme in the STFM workshops was privileging difficulties. FPs may struggle to get privileges approved by hospital credentialing committees because there is not a consistent national standard set of FP maternity care privileges, and requirements to obtain privileges at any individual hospital are often dependent on local or regional needs and not based on an individual provider’s experience. Institutional requirements vary. Some may require completion of a FM residency with specific obstetrics curricula and adequate volume without defining a number, while others may require high procedural numbers and fellowship training in order to apply for even basic maternity privileges.

Workshop attendees recommended FPs involved in writing privileging documents refer to the AAFP-ACOG joint statement of cooperative practice and hospital privileges.26 The joint statement emphasizes that providers should be granted privileges commensurate with their training and experience and not their specialty. Since allowing another specialty to have control over FP privileging can lead to unrealistic requirements, STFM workshop participants also strongly advised that FPs with maternity care skills have representation on hospital credentialing committees and participate in writing their department’s maternity privileging requirements.

When writing new privileges, workshop attendees suggested that FPs consult other local institutions to make sure privileges include all desired options of maternity care that an FP may provide, even if not desired by an individual provider. Adding additional procedures later (such as external cephalic version, when only cesarean section was initially requested, for example) may prove difficult and unintentionally limit the scope of practice for future FPs at that institution.

To facilitate privileging, workshop attendees recommended FPs keep logs of procedures performed as well as outcomes data to support their privileging application. FM faculty from several programs recommended including a provision for proctoring new providers to ensure baseline and ongoing quality practice patterns.27 Of the privileging documents reviewed during the STFM workshops, no institution required fellowship training to attend normal vaginal deliveries, and faculty experts in the workshops agreed that proficient FM residency training and competency in maternity care is sufficient to obtain normal vaginal delivery hospital privileges (Table 2).28

The AAFP has recently updated their privileging section for members to include “Medical Staff Bylaws,” “Steps for Hospital Credentialing and Privileging,” and “Avoiding a Hospital Privilege Dispute.” This webpage resource contains a checklist for FPs to determine if they should pursue legal action in the event of a privileging dispute. There are precedents, including one in California where the doctor was still denied privileges after an appeal (Eric Runte, Plaintiffs-appellants v Sonora Community Hospital, Donovan Tee,; Hillside Obstetrics and Gynecology, Medical Group, Inc, Louis Erich, Sonora Medical Group, Inc, Defendants-appellees, 236 F.3d 1148 [9th Cir. 2001]) and another where a doctor and health care system were able to resolve their privileging conflict through mediation with the assistance of the Texas Medical Association (Dr Jeff Alling and Wise Regional Health System).29

The related issue of obtaining privileges for maternity care after a lapse in practice can be very challenging. Each hospital has its own policy regarding reentry, and many hospitals do not have provisions in the standard credentialing documents. There are no uniform guidelines on this topic; the requirements vary widely even among major academic centers. Workshop presenters recommended FPs seeking reentry into maternity care consider contacting the STFM Family-Centered Maternity Care Collaborative or the “Famdel” listserv to help locate local and national mentors for assistance through this process.1

Developing and Maintaining Clinical Volume/Competency

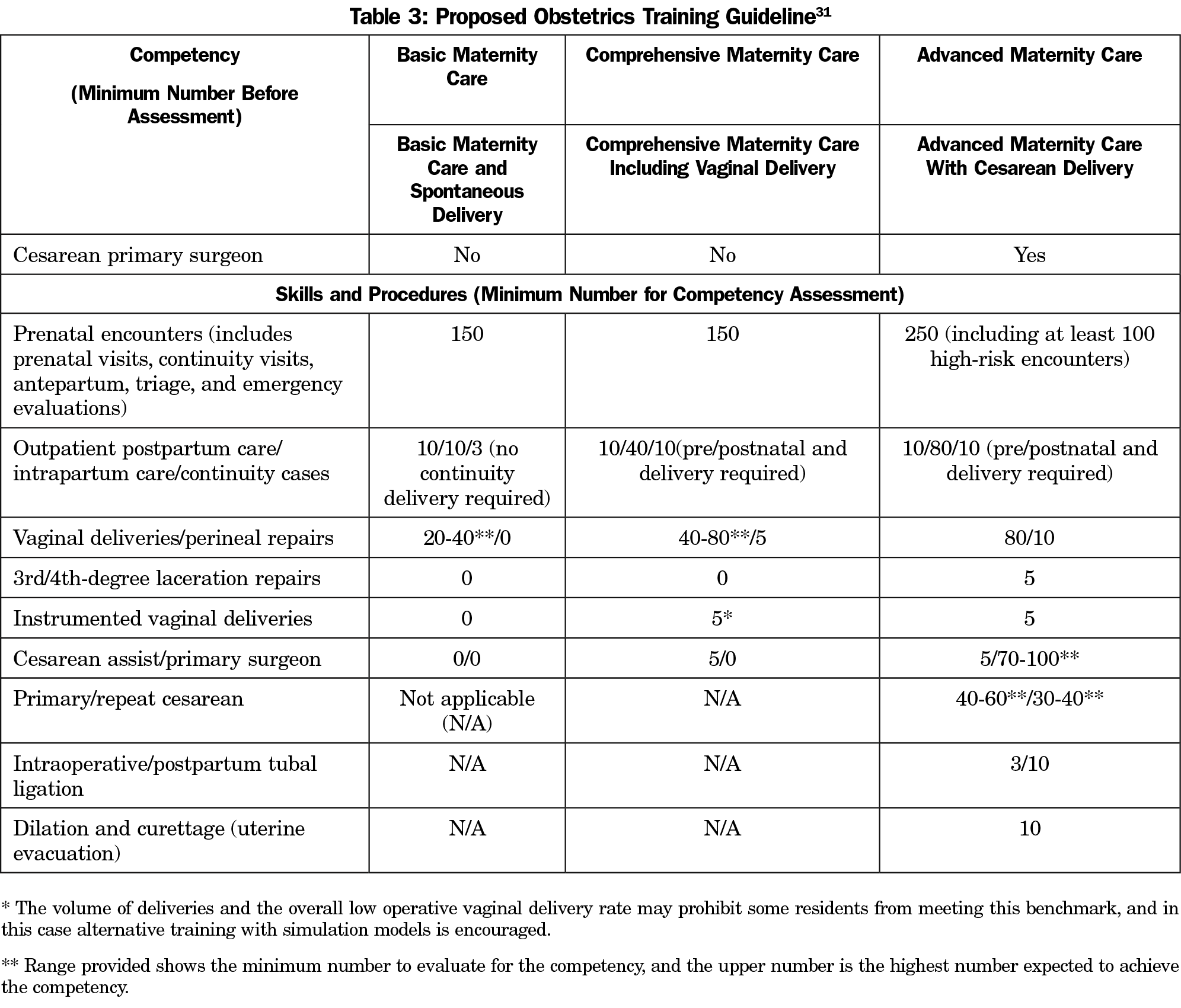

For FP maternity care providers, achieving adequate delivery volume is a concern that starts in residency training and continues throughout their careers. In the United States, FM residency programs vary greatly in how much emphasis is placed on maternity care. Some programs expect graduates to attend as many as 200 deliveries in residency while at others, residents interested in maternity care struggle to attend 40. Historically, the minimum residency requirement was attending 40 deliveries; however, in 2014, numerical requirements were removed by the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education because many programs struggled to meet this benchmark.30

In FM residency programs, obtaining volume varies regionally and makes national requirements for maternity care difficult to standardize. A recent survey found that programs where trainees received supervision by FM faculty preceptors, attended 80 or more deliveries during residency, and had decision-making autonomy on OB rotations were more likely to continue to provide maternity care after residency.5

In 2014, a work group assembled from STFM educators proposed a competency-based assessment system for maternity care procedures including suggestions for minimum procedural numbers to assess competency during training.31 While this system is still in a trial stage, there is discussion that this system could provide clarification of FM competency and perhaps assist FPs to maintain scope of practice in maternity care in the future (Table 3).31

FM residents interested in providing maternity care after residency may find it difficult if their residency does not have appropriate resources to support such interest. At low-volume programs, workshop attendees suggested that residents augment their core rotations with additional maternity care experience by taking extra obstetrics call from other residents who are less interested, or using elective time to increase their clinical experience. It was also recommended that FM residencies support interested FM residents from low-volume sites by establishing mentorship with FM faculty for interested trainees, collaborating with local maternity care providers or OB/GYN training programs to create innovative education opportunities, and by working to support national efforts through STFM to maintain a national database of maternity care elective sites. In an effort to support FM residencies that lack solid maternity care training, workshop attendees also suggested that FM residencies with strengths in maternity care offer to host residents from other sites.

Once in practice, FPs may struggle to maintain a sufficient volume of maternity patients to maintain competency. Creating maternity care volume in low-volume sites can be difficult, but some FP practices have successfully improved volume by tailoring their practices to the needs of the community through partnerships with community and public health organizations. During the STFM workshops, attendees presented and discussed known models of FM clinics that collaborate with community agencies and specialize in teen pregnancy, opiate and multiple drug addiction, HIV/AIDS patients, and prenatal group visits tailored to underserved women. For example, some FPs prescribe buprenorphine and take referrals from OB/GYNs for prenatal management of women with addiction. FPs in some practices also care for babies of these mothers in the critical neonatal withdrawal period, providing continuity as “dyad specialists.” FP maternity care providers can provide close follow-up for patients with gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, obesity, and other high-risk conditions which may improve the overall care of women and the outcome of future pregnancies.

Workshop attendees also showcased group prenatal care as a unique and important model of care that is associated with improved patient satisfaction, reduction in health disparities, and positive maternal-fetal outcomes.32 FPs with experience in group care in other realms such as diabetes or chronic pain groups can market these skills to maternity populations, and there are examples of FP practices that have had success with the type of models that were reported at the workshops. Group prenatal care may also be a way to recruit new FP maternity care providers, as a recent survey of FM residency program directors found that group prenatal visits were associated with residents being twice as likely to provide maternity care and participate in obstetrics fellowships after graduation.24

Ensuring that patients and insurance providers are aware that FPs provide maternity care by including them in provider listings and implementing proper marketing might also improve patient volume.33,34 Another novel idea to increase volume that has been previously successful is to offer free pregnancy tests and then provide prenatal care for those who choose to continue their pregnancy.35 Workshop attendees recommended acting as a referral source to provide vaginal birth after cesarean services, collaborating with midwifery practices, and partnering with rural hospitals to accept transfers as possible ways to generate obstetrical volume.

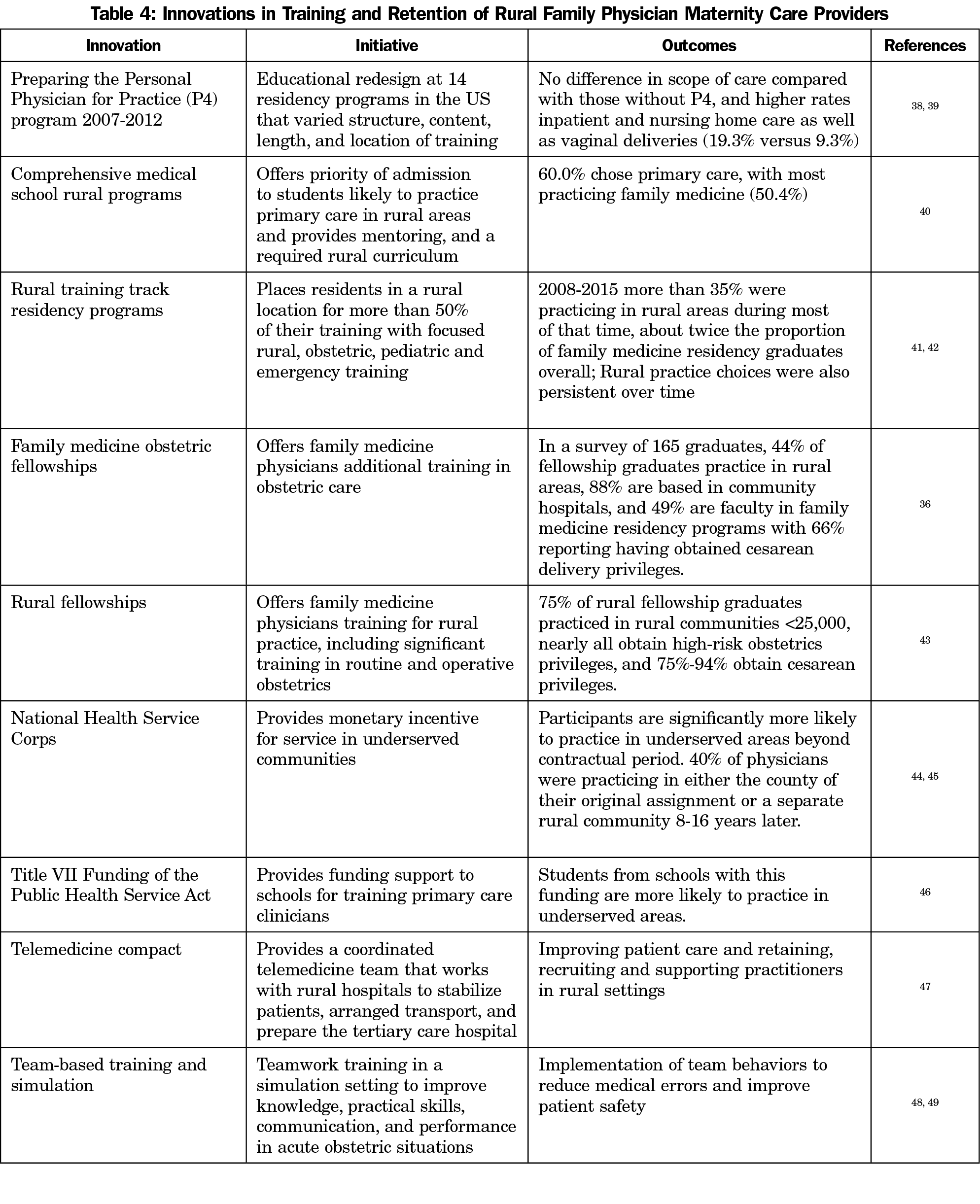

Rural FP maternity care providers face unique challenges. They may be called upon to provide care to high-risk patients who have no other options for care, and to perform operative deliveries in settings where obstetrical volume is low.36 In one recent survey, 55% of the rural hospitals had FPs on staff attending deliveries, and 32% had FPs performing cesarean deliveries.9 The ACOG’s position statement on practice considerations for rural and low-volume obstetrics states that support of health care providers in these settings is a shared responsibility among community, government, payers, and health care facilities.37 Table 4 lists innovations that have been used to recruit, train, and support those who choose to practice in rural settings.36, 38-49 Nearly all of these programs require funding and collaboration with stakeholders such as communities or the government in order to be successful in addressing maternal health disparities in rural populations.

One result of the many obstacles FP maternity care providers may encounter is burnout, defined here as being at high risk for leaving maternity care practice. One model of FM maternity care is for an individual physician to provide all the prenatal and delivery care with a commitment to come to the delivery as a model of continuity of care for the woman and her family. However, this may not be feasible for every FP wanting to provide maternity care when they do not have the support needed to balance work, family, and personal responsibilities. Workshop attendees recommended identifying alternative patient coverage strategies to make providing maternity care more feasible. These models could include call sharing with other FPs, CNMs, and/or OB/GYNs within the practice, hospital system, birth center, or community. In-house call coverage or laborist models of care provide an alternative to the traditional call coverage models. In addition, setting reasonable limits in patient volume and/or complexity may help FPs maintain balance and not become overburdened.

Ensuring that FPs are adequately compensated for their efforts either monetarily or with time off can also help reduce the risk of burnout. Workshop participants discussed practice models that ensure that those attending deliveries are released from outpatient clinical care after an overnight shift or receive vacation or administrative time as reimbursement for after-hours work as potential ways to temper burnout risk. Workshop attendees also reported that FPs providing intrapartum care and deliveries generally received higher pay for providing these services, but they also often require higher malpractice insurance premiums than those who do not attend births.50 It was recommended that FPs negotiating new contracts ensure their base salary and productivity incentives are sufficient to compensate their insurance expense in addition to the after-hours work necessary to provide maternity care.

Burnout can present itself with decreased fulfillment in one’s work. Qualitative studies identify the emotional aspects of providing intrapartum care as being influential in the decision of whether to practice obstetrics. A bad outcome associated with a birth may carry a larger burden of emotional stress for some providers and include feelings of guilt or inadequacy or fear of litigation. On the other hand, the extreme joy of participating in births and the continuity of care that doing so offers is an emotion that often sustains FP maternity care providers in their work. There was a strong opinion among workshop attendees that intentionally creating specific professional support around bad outcomes while celebrating the unique joys of providing intrapartum care and sharing this support with learners may help to support FP maternity care providers to continue to practice while inspiring a new generation.51,52

Workshop participants encouraged FP maternity care providers to be actively involved in mentoring learners to combat burnout by, for example, offering free attendance to ALSO courses for medical and nursing students, and/or getting learners involved in group prenatal care.

As the FP maternity care provider workforce shrinks, FP maternity care providers may feel isolated and unsupported as they deal with these aforementioned challenges. Workshop presenters all agreed that FP maternity care providers may be more successful if they identify mentors to assist in developing an individualized action plan (see Appendix A at https://journals.stfm.org/media/2609/goldstein-appendix-a-fm2018.pdf), utilizing the solutions outlined above to overcome personal and local barriers.28 In addition to local mentorship, online communities and listservs are available to support new or returning FP maternity care providers and provide mentorship and guidance utilizing individual perspectives from other areas of the United States and Canada.*†

FP maternity care provider scarcity is multifaceted. While malpractice concerns are often cited as a reason that FPs do not provide maternity care, there is very limited evidence of this in recent literature. One study in Michigan showed no impact of malpractice burden, but did show a trend in rural FPs being four times more likely to withdraw from obstetric care than their urban counterparts.54 Intangible lifestyle issues, problems with interprofessional relationships, competency concerns, privileging, and lack of mentorship and support in problem solving all likely contribute to burnout or a trend in lack of interest early in one’s career.55

This article provides recommendations to address many of the challenges facing FP maternity care providers and highlights how FPs are particularly suited to fill needs of individual communities (Table 5). With the decline in the number of FP maternity care providers, there is a need to support those who still choose to practice, particularly when the ACOG projects such a large shortage of obstetric providers by 2030.1

FPs fill an important niche, addressing racial and socioeconomic disparities through public health collaboration and community engagement. Further research on FM patient-oriented outcomes is necessary to emphasize that FPs continue to provide safe, cost-effective, high-quality maternity care in the 21st century. While some literature exists, it is limited.56-58 Additional research will likely validate the role FM has in stabilizing the nation’s declining access to maternity services while providing cost-effective care and improving health outcomes for rural and urban underserved populations.

The provision of high-quality and safe maternity care to rural and underserved communities is a shared public health responsibility. All stakeholders, including specialty professional societies (ACOG, AAFP, and ACNM), must collaborate to address workforce shortages including supporting the continued provision of maternity care within family medicine. Family physicians providing maternity care need to encourage all levels of national and educational leadership to promote these efforts as a vital component of the specialty.

* To subscribe to famdel, simply send an email message to listserv@lsv.uky.edu. Leave the subject line blank. In the body text type “subscribe FAMDEL (your full name).” To receive the digest in which messages are grouped together and sent once a day send the following e-mail message to listserv@lsv.uky.edu: “subscribe famdel (Your name without brackets) set famdel mail digest.” Current subscribers can post messages by emailing famdel@lsv.uky.edu (include a descriptive subject line).

† To join STFM CONNECT go to https://connect.stfm.org/home, for STFM members only. To join the Family-Centered Maternity Care collaborative update your connections by going to the “My Connections” section of your STFM profile and modify your selections.

Acknowledgments

This paper was inspired by ideas brought together at a preconference and seminar at the 2016 and 2017 STFM Annual Spring Conferences, but the paper has not been presented or published elsewhere.

In addition to their own institutions, the authors thank the following institutions and individuals for their willingness to share resources to support family physician maternity care providers:

- Boston University (Jordana Price, MD, Jennifer Pfau, MD, Richard H. Long, MD, Michelle J. Sia, DO)

- Columbia St Mary’s Family Medicine Residency, Medical College of Wisconsin (Camille Garrison, MD, Paul Koch, MD, MS, Karen Lupa, CNM)

- Mountain Area Health Education Center- Asheville, North Carolina (Dan Frayne, MD)

- Oregon Health Sciences University (Jennifer DeVoe, MD, DPhil)

- University of California, Davis (Wetona Suzanne Eidson-Ton, MD)

- University of Massachusetts-Worchester (Lucy Candib, MD, Navid Roder, MD, Stephanie Carter-Henry, MD)

- University of New Mexico, (Lawrence Leeman, MD, MPH)

- University of North Carolina (Martha Carlough MD, MPH, Narges Farahi, MD, Siobhan Wulff, Rn, BS, C-EFM)

- University of Wisconsin, Madison (Lee Dresang, MD, Cynthie Anderson, MD Emily Beaman, CNM).

References

- Rayburn WF. The Obstetrician/gynecologist Workforce in the United States: Facts, Figures, and Implications 2017. Washington, DC: American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2017.

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Rayburn WF. Relocation of obstetrician-gynecologists in the United States, 2005-2015. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):543-550. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001901

- Rayburn WF, Petterson SM, Phillips RL. Trends in family physicians performing deliveries, 2003-2010. Birth. 2014;41(1):26-32. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12086

- Rayburn WF, Tracy EE. Changes in the Practice of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2016;71(1):43-50. https://doi.org/10.1097/OGX.0000000000000264

- Sutter MB, Prasad R, Roberts MB, Magee SR. Teaching maternity care in family medicine residencies: what factors predict graduate continuation of obstetrics? A 2013 CERA program directors study. Fam Med. 2015;47(6):459-465.

- Tong STC, Makaroff LA, Xierali IM, et al. Proportion of family physicians providing maternity care continues to decline. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(3):270-271. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2012.03.110256

- Cohen D, Coco A. Declining trends in the provision of prenatal care visits by family physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(2):128-133. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.916

- Eden AR, Peterson LE. Impact of potential accreditation and certification in family medicine maternity care. Fam Med. 2017;49(1):14-21.

- Kozhimannil KB, Casey MM, Hung P, Han X, Prasad S, Moscovice IS. The rural obstetric workforce in US hospitals: challenges and opportunities. J Rural Health. 2015;31(4):365-372. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12112

- Tong ST, Makaroff LA, Xierali IM, Puffer JC, Newton WP, Bazemore AW. Family physicians in the maternity care workforce: factors influencing declining trends. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(9):1576-1581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-012-1159-8

- Barreto T, Peterson LE, Petterson S, Bazemore AW. Family physicians practicing high-volume obstetric care have recently dropped by one-half. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(12):762.

- Xierali IM, Puffer JC, Tong STC, Bazemore AW, Green LA. The percentage of family physicians attending to women’s gender-specific health needs is declining. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(4):406-407. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2012.04.110290

- Young RA. Maternity Care Services Provided by Family Physicians in Rural Hospitals. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(1):71-77. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160072

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 586: health disparities in rural women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 Pt 1):384-388.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Maternal/Child Care (Obstetrics/Perinatal Care). https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/maternal-child.html. Published November 1, 2017. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- Pecci CC, Hines TC, Williams CT, Culpepper L. How we built our team: collaborating with partners to strengthen skills in pregnancy, delivery, and newborn care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(4):511-521. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2012.04.110160

- Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality. TeamStepps. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/index.html. Published May 20, 2016. Accessed September 24, 2017.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG District II Safe Motherhood Initiative (SMI) - ACOG. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Districts/District-II/Safe-Motherhood-Initiative. Accessed August 14, 2017.

- Black RS, Brocklehurst P. A systematic review of training in acute obstetric emergencies. BJOG. 2003;110(9):837-841. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2003.02488.x

- American Academy of Family Physicians. ALSO® Provider Course. http://www.aafp.org/cme/cme-topic/all/also-provider.html. Published October 29, 2013. Accessed August 14, 2017. Accessed August 22, 2017.

- Taylor HA, Kiser WR. Reported comfort with obstetrical emergencies before and after participation in the advanced life support in obstetrics course. Fam Med. 1998;30(2):103-107.

- Wouk K, Tully KP, Labbok MH. Systematic review of evidence for Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative Step 3. J Hum Lact. 2017;33(1):50-82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334416679618

- Centering Healthcare Institute. Evaluation & Research. https://www.centeringhealthcare.org/why-centering/evaluation-research. Accessed August 24, 2017.

- Barr WB, Tong ST, LeFevre NM. Association of group prenatal care in US family medicine residencies with maternity care practice: a CERA secondary data analysis. Fam Med. 2017;49(3):218-221.

- Family Medicine Education Consortium. IMPLICIT—An FMEC Collaborative. http://www.fmec.net/implicitnetwork.htm. Accessed August 24, 2017.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. AAFP—ACOG joint statement of cooperative practice and hospital privileges. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58(1):277-278.

- Marder RJ, Marder R, Smith MA, Sagin T. Proctoring and Focused Professional Practice Evaluation: Practical Approaches to Verifying Physician Competence. Marblehead, MA: HC Pro, Inc; 2006.

- Goldstein JT. Sticking with it: mentoring maternal child health providers for the long haul. STFM Resource Library. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/sticking-with-it-mentoring-materna. Accessed August 24, 2017.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Avoiding a hospital privilege dispute. https://www.aafp.org/practice-management/administration/privileging/avoid-disputes.mem.html. Accessed March 10, 2018.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in family medicine. http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/120_family_medicine_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2017.

- Magee SR, Eidson-Ton WS, Leeman L, et al. Family Medicine Maternity Care Call to Action: Moving Toward National Standards for Training and Competency Assessment. Fam Med. 2017;49(3):211-217.

- Nielsen PE. Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(4):993-994. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816bf4be

- Rosenbloom J. The Handbook of Employee Benefits: Health and Group Benefits 7/E. New York: McGraw Hill Professional; 2011.

- Harris KM. How do patients choose physicians? Evidence from a national survey of enrollees in employment-related health plans. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(2):711-732. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.00141

- Oat-Judge J, Galvin SL, Frayne DJ. Free pregnancy testing increases maternity care volume in family medicine residencies. Fam Med. 2015;47(6):470-473.

- Chang Pecci C, Leeman L, Wilkinson J. Family medicine obstetrics fellowship graduates: training and post-fellowship experience. Fam Med. 2008;40(5):326-332.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice considerations for rural and low-volume obstetric settings - ACOG. https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Position-Statements/Practice-Considerations-for-Rural-and-Low-Volume-Obstetric-Settings. Accessed October 5, 2017.

- Eiff MP, Hollander-Rodriguez J, Skariah J, et al. Scope of practice among recent family medicine residency graduates. Fam Med. 2017;49(8):607-617.

- Skariah JM, Rasmussen C, Hollander-Rodriguez J, et al. Rural curricular guidelines based on practice scope of recent residency graduates practicing in small communities. Fam Med. 2017;49(8):594-599.

- Rabinowitz HK, Petterson SM, Boulger JG, et al. Comprehensive medical school rural programs produce rural family physicians. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(12):1350.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Rural practice: graduate medical education for (Position Paper). https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/rural-practice.html. Published April 6, 2015. Accessed March 3, 2018.

- University of Washington School of Medicine. Family medicine rural training track residencies: 2008-2015 graduate outcomes. https://depts.washington.edu/fammed/rhrc/publications/family-medicine-rural-training-track-residencies-2008-2015-graduate-outcomes/. Accessed March 11, 2018.

- Acosta DA. Impact of rural training on physician work force: the role of postresidency education. J Rural Health. 2000;16(3):254-261. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2000.tb00469.x

- Lee DM, Nichols T. Physician recruitment and retention in rural and underserved areas. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2014;27(7):642-652. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHCQA-04-2014-0042

- Cullen TJ, Hart LG, Whitcomb ME, Rosenblatt RA. The National Health Service Corps: rural physician service and retention. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1997;10(4):272-279.

- Krist AH, Johnson RE, Callahan D, Woolf SH, Marsland D. Title VII funding and physician practice in rural or low-income areas. J Rural Health. 2005;21(1):3-11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00056.x

- Mann S, McKay K, Brown H. The Maternal Health Compact. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(14):1304-1305. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1700485

- Marshall NE, Vanderhoeven J, Eden KB, Segel SY, Guise J-M. Impact of simulation and team training on postpartum hemorrhage management in non-academic centers. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28(5):495-499. https://doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2014.923393

- Merién AE, van de Ven J, Mol BW, Houterman S, Oei SG. Multidisciplinary team training in a simulation setting for acute obstetric emergencies. Obstet Anesthes Dig. 2011;31(2):83-84. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aoa.0000397113.95428.cb

- Larimore WL, Sapolsky BS. Maternity care in family medicine: economics and malpractice. J Fam Pract. 1995;40(2):153-160.

- Dove M, Dogba MJ, Rodríguez C. Exploring family physicians’ reasons to continue or discontinue providing intrapartum care: qualitative descriptive study. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(8):e387-e393.

- Koppula S, Brown JB, Jordan JM. Experiences of family medicine residents in primary care obstetrics training. Fam Med. 2012;44(3):178-182.

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Group on Family-Centered Maternity Care. http://www.stfm.org/Groups_old/GroupPagesandDiscussionForums/Family-CenteredMaternityCare. Accessed August 24, 2017.

- Xu X, Siefert KA, Jacobson PD, Lori JR, Gueorguieva I, Ransom SB. Malpractice burden, rural location, and discontinuation of obstetric care: a study of obstetric providers in Michigan. J Rural Health. 2009;25(1):33-42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00196.x

- Eden AR, Peterson LE. Challenges faced by family physicians providing advanced maternity care. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(6):932-940. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2469-2

- Abenhaim HA, Welt M, Sabbah R, Audibert F. Obstetrician or family physician: are vaginal deliveries managed differently? J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007;29(10):801-805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32631-7

- Aubrey-Bassler K, Cullen RM, Simms A, et al. Outcomes of deliveries by family physicians or obstetricians: a population-based cohort study using an instrumental variable. CMAJ. 2015;187(15):1125-1132. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.141633

- Homan FF, Olson AL, Johnson DJ. A comparison of cesarean delivery outcomes for rural family physicians and obstetricians. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(4):366-372. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2013.04.120203

- Dresang LT, González MMA, Beasley J, et al. The impact of Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics (ALSO) training in low-resource countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;131(2):209-215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.05.015

There are no comments for this article.