Background and Objectives: Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a silent epidemic affecting one in three women. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends routine IPV screening for women of childbearing age, but actual rates of screening in primary care settings are low. Our objectives were to determine how often IPV screening was being done in our system and whether screening initiated by medical assistants or physicians resulted in more screens.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective chart review to investigate IPV screening practices in five primary care clinics within a university-based network in Northern California. We reviewed 100 charts from each clinic for a total of 500 charts. Each chart was reviewed to determine if an IPV screen was documented, and if so, whether it was done by the medical assistant or the physician.

Results: The overall frequency of IPV screening was 22% (111/500). We found a wide variation in screening practices among the clinics. Screening initiated by medical assistants resulted in significantly more documented screens than screening delivered by physicians (74% vs 9%, P<0.001).

Conclusions: IPV screening is an important, but underdelivered service. Using medical assistants to deliver IPV screening may be more effective than relying on physicians alone.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a silent epidemic affecting one in three women during their lifetime.1 IPV leads to injuries and death from physical and sexual assault, sexually transmitted infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, unintended pregnancy, chronic pain, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety, substance abuse, and suicide.2 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that clinicians routinely screen women of childbearing age for IPV (“B” recommendation),3 but research shows that actual rates of screening in primary care settings are low.4 In addition, there is a wide range of screening strategies across different medical practices, with some clinics assigning nonphysician personnel (ie, nurse/midwife, social worker, medical assistant) to do screening, while others rely on physicians.5 There is no consensus on the optimal screening protocol. A randomized trial of three screening protocols (self-administered survey, nonphysician personnel interview, and physician interview) showed similar rates of IPV disclosure in a controlled environment.6 However, in real-world settings where lack of office protocols and limited time are common barriers for physicians,7-10 results are inconsistent and contradictory on the optimal way of delivering IPV screening.11-12

With violence against women in the national spotlight due to the #MeToo movement,13 we set out on a quality improvement initiative to identify opportunities to enhance IPV screening within our university-based network of primary care clinics. Our objectives were to determine (1) how often IPV screening was being documented, and (2) whether screening initiated by nonphysician staff or physicians resulted in more documented screens.

Setting

We examined IPV screening practices in five primary care clinics within a university-based network in Northern California. Collectively, these clinics provide care for 40,000 people and have 52 providers, including family physicians and general internists. Among the participating clinics, one had an established protocol of medical assistants doing screening, while the other four locations had an established protocol of physicians doing screening. All five clinics subscribed to a policy of IPV screening consistent with the 2013 USPSTF guidelines. Standard procedures to support IPV screening and follow-up in the event of IPV disclosure were identical across clinics. The clinics were within 20 miles of one another and served a similar patient population (ie, insured, working, upper middle class, racially diverse). Physician characteristics were similar across the clinics (ie, gender, average years of clinical experience).

Design

We conducted a retrospective chart review in the electronic health record. Our inclusion criteria were: (1) female patient of childbearing age (defined as 18 to 49 years), (2) preventive exam as the reason for visit, and (3) charts completed on or after May 1, 2017. We reviewed 100 charts from each study clinic for a total of 500 charts. Charts were reviewed in chronological order until the target was achieved. Each chart was reviewed to determine if an IPV screen was documented. If a screen was completed, the reviewer determined whether it was done by the physician or the medical assistant, and what questions were asked. Data were also collected on the patients’ age and the screeners’ gender. The chart review was conducted by a trained clinical scribe (L.S.) using a checklist/spreadsheet developed for the project under the supervision of a faculty mentor (S.L.).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine the frequency distribution of patients screened, patients’ age, and screeners’ gender. Pearson χ2 test and Fisher exact test were performed to discover associations between the number of patients screened by clinic site, screener type (physician or medical assistant), patient age, and screener gender. A binary logistic regression model was performed to predict patient screening based on patient age as a continuous variable. All analyses were done using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). The Institutional Review Board of Stanford University School of Medicine granted this study a formal exemption.

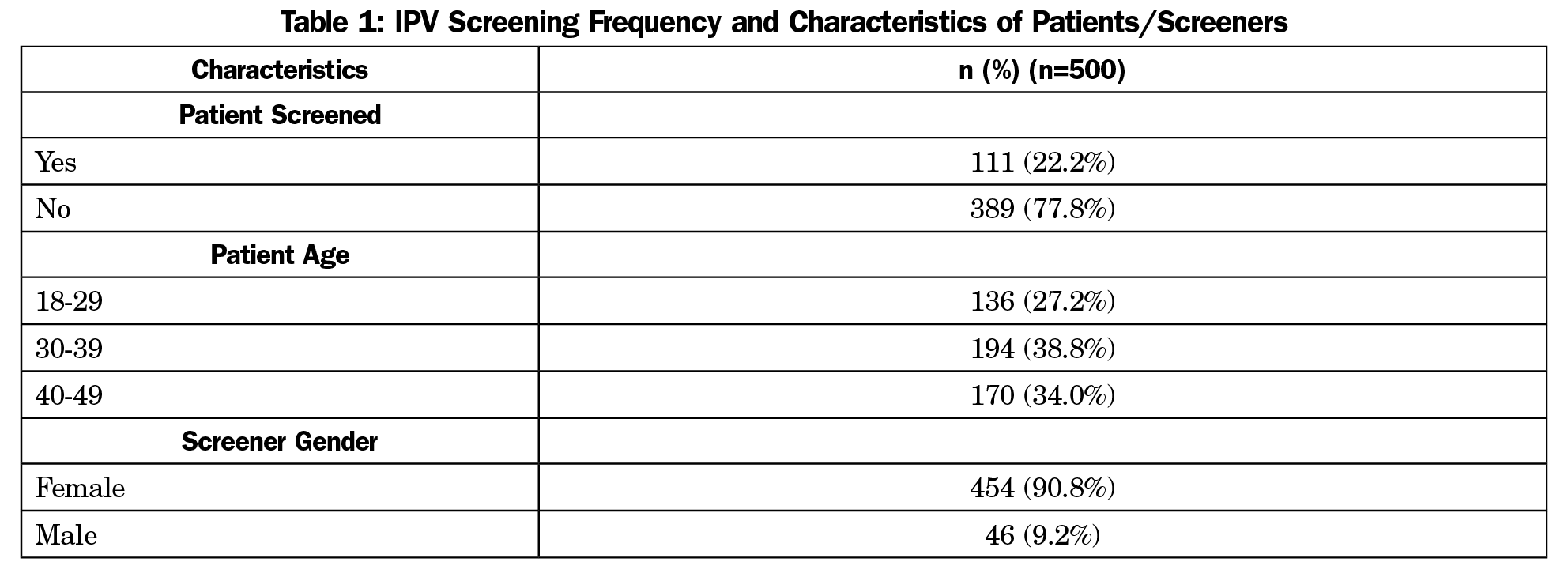

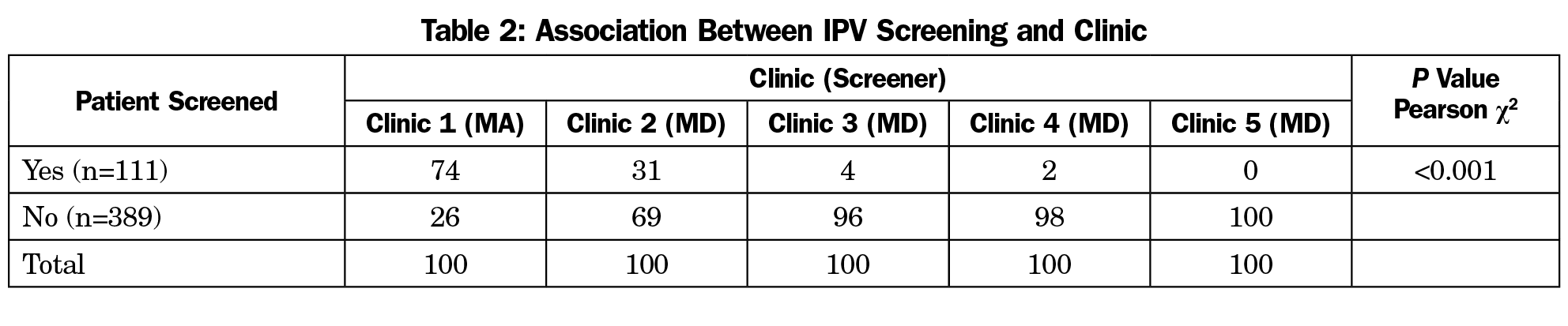

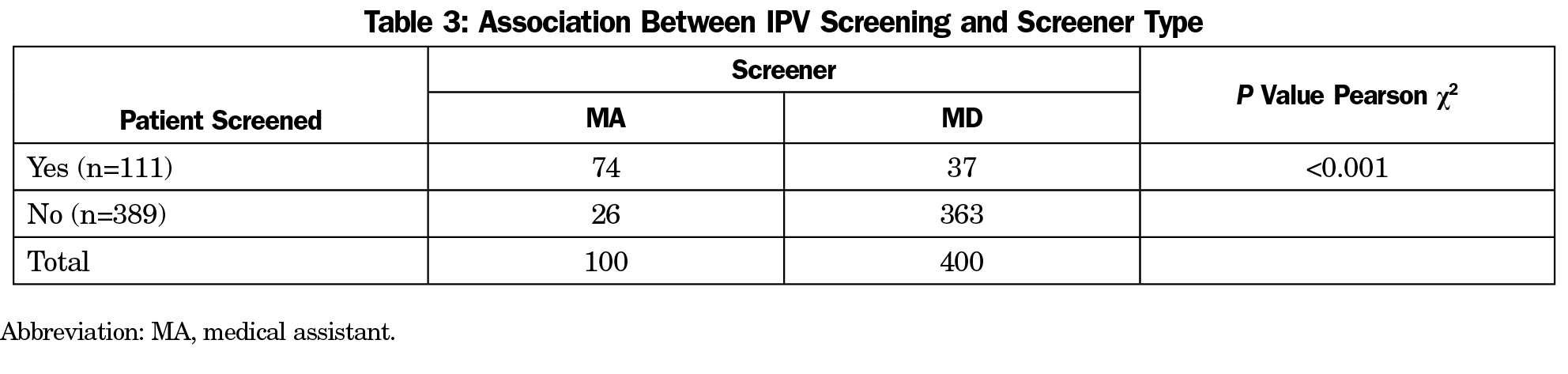

Patient and screener characteristics are shown in Table 1; these were similar across the five study clinics. The overall frequency of IPV screening across five primary care clinics within our academic medical center was 22% (111/500; Table 1). We identified a wide variation in the frequency of screening documentation between clinics, ranging from 0%-74% (Table 2). Screening performed in the clinic where the screener was a medical assistant resulted in significantly more documented screens than in clinics where the physician was the screener (74/100 [74%] vs 37/400 [9%], P<0.001, Table 3). The most commonly used screening questions were: (1) “Because difficult relationships can cause health problems, we are asking all of our patients the following question: ‘Does a partner, or anyone at home, hurt, hit, or threaten you?’” and (2) “Is anyone at home hurting you, threatening you, or making you afraid?”

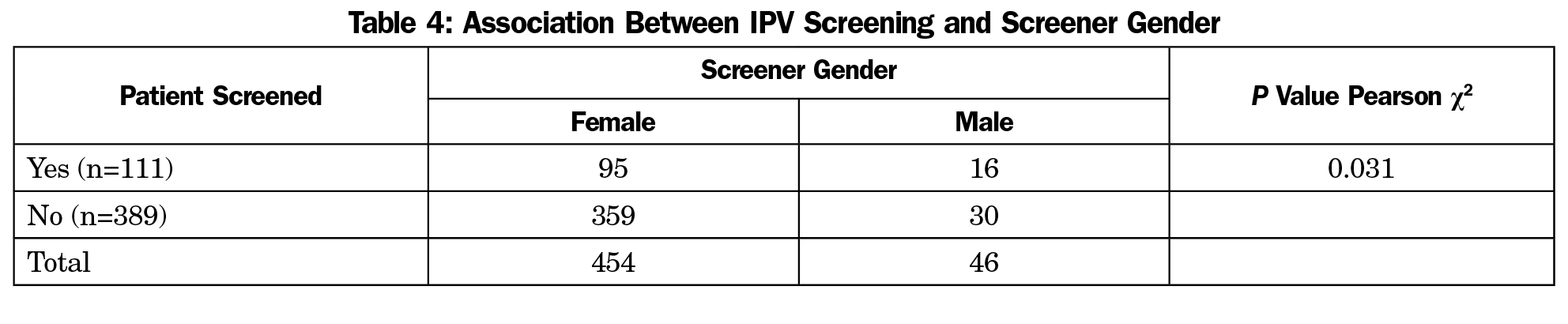

Male screeners were associated with more documented screens than female screeners (16/46 [35%] vs 95/454 [21%], P=0.031), though there was a heavy skew in our female-to-male ratio (Table 4). Patient age was associated with documented screens (age 18-29 years: 24/136 [17%]; age 30-39 years: 36/194 [19%]; age 40-49 years: 51/170 [30%]; P=0.011, Table 5). Binary logistic regression showed that patient age was a significant predictor of being screened for IPV (χ2=8.311, df=1 and P=0.004).

Our study identified opportunities to improve IPV screening in our primary care system—lessons we believe might be helpful to other systems. First, we found a wide variation in the frequency of screening documentation (0%-74%) among clinics within the same primary care network. This is despite the fact that standard policies and guidelines to support screening and follow-up in the event of disclosure were identical across clinics. This suggests that policies alone are insufficient and that a universal workflow, training, and screening protocol might be needed to help eliminate disparities in care quality and adherence to evidence-based screening guidelines within a system. Second, we found that IPV screening performed in the clinic where the screener was a medical assistant resulted in significantly more documented screens than in the clinics where the screener was a physician. Though previous studies have shown no difference in the rates of IPV screening and disclosure between physician and nonphysician methods in a controlled setting,6 in our real-world setting, a medical assistant protocol was more effective in completing screens.

Nonphysician screening has been shown in a recent randomized controlled trial to be superior to a physician-only approach for another USPSTF recommendation, namely alcohol abuse screening.14 In a study of 54 primary care clinics in an integrated health care system (Kaiser Permanente Northern California), screening rates were highest in the nonphysician provider and medical assistant arm (51%), followed by the primary care physician arm (9%), and the control arm (3.5%). Their study and ours together add to a growing body of literature suggesting that screening by medical assistants with intervention and referral by physicians as needed can be a feasible model for increasing evidence-based screenings.

Our study is limited by its retrospective, nonrandomized design focused on a single institution. Our chart review methodology may not have captured the true frequency of screening across the system; our reported screening frequency of 22% is probably driven by the clinic with a medical assistant screening protocol. Although we found associations between screener gender and patient age with IPV screening, the study was insufficiently powered to examine the clinical significance of screener and patient factors. Lastly we only measured the frequency of screening documentation and not the rates of IPV disclosure.

Conclusions

IPV screening is an important, but underdelivered service. Using medical assistants to perform IPV screening may be a more effective real-world strategy than relying on physicians alone.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Harise Stein for her contributions to this work, as well as her many years of research and advocacy on the topic of intimate partner violence. Previous presentations: Part of this manuscript was presented as a poster at the STFM Annual Spring Conference in Washington, DC, May 5-9, 2018.

References

- Smith SG, Chen J, Basile KC, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010-2012 State Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/NISVS-StateReportBook.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2018.

- Nelson HD, Bougatsos C, Blazina I. Screening women for intimate partner violence: a systematic review to update the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(11):796-808, W-279, W-280, W-281, W-282. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00447

- Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for intimate partner violence and abuse of elderly and vulnerable adults: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(6):478-486. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-6-201303190-00588

- Rodriguez MA, Bauer HM, McLoughlin E, Grumbach K. Screening and intervention for intimate partner abuse: practices and attitudes of primary care physicians. JAMA. 1999;282(5):468-474. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.5.468

- Sprague S, Slobogean GP, Spurr H, et al. A scoping review of intimate partner violence screening programs for health care professionals. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0168502. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0168502

- Chen PH, Rovi S, Washington J, et al. Randomized comparison of 3 methods to screen for domestic violence in family practice. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(5):430-435. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.716

- Erickson MJ, Hill TD, Siegel RM. Barriers to domestic violence screening in the pediatric setting. Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):98-102. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.1.98

- Cummins A, Little D, Seagrave M, Ricken A, Esparza V, Richardson-Nassif K. Vermont family practitioners’ perceptions on intimate partner violence. Presentation at North American Primary Care Research Group (NAPCRG) 30th Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA.

- Gerber MR, Leiter KS, Hermann RC, Bor DH. How and why community hospital clinicians document a positive screen for intimate partner violence: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6(1):48. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-6-48

- McGrath ME, Bettacchi A, Duffy SJ, Peipert JF, Becker BM, St Angelo L. Violence against women: provider barriers to intervention in emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4(4):297-300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03552.x

- McFarlane J, Christoffel K, Bateman L, Miller V, Bullock L. Assessing for abuse: self-report versus nurse interview. Public Health Nurs. 1991;8(4):245-250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1446.1991.tb00664.x

- Canterino JC, VanHorn LG, Harrigan JT, Ananth CV, Vintzileos AM. Domestic abuse in pregnancy: A comparison of a self-completed domestic abuse questionnaire with a directed interview. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181(5 Pt 1):1049-1051. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70079-7

- Zacharek S, Dockterman E, Edwards HS. TIME person of the year 2017: The silence breakers. Time. December 18, 2017. http://time.com/time-person-of-the-year-2017-silence-breakers. Accessed January 24, 2018.

- Mertens JR, Chi FW, Weisner CM, et al. Physician versus non-physician delivery of alcohol screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment in adult primary care: the ADVISe cluster randomized controlled implementation trial. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2015;10(1):26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-015-0047-0

There are no comments for this article.