Background and Objectives: Chief resident leadership competencies are neither clear nor standardized. The goal of this project was to identify specific leadership skills for chief residents and to develop a self-assessment tool.

Methods: Chief residents from 10 family medicine residencies participated in focus groups to identify leadership skills required to be an effective chief resident. The ideas generated by participants were grouped into 10 competencies and a self-assessment tool was developed. The tool has been used to help chief residents self-assess their leadership strengths and weaknesses, and to identify teaching priorities for biannual leadership workshops.

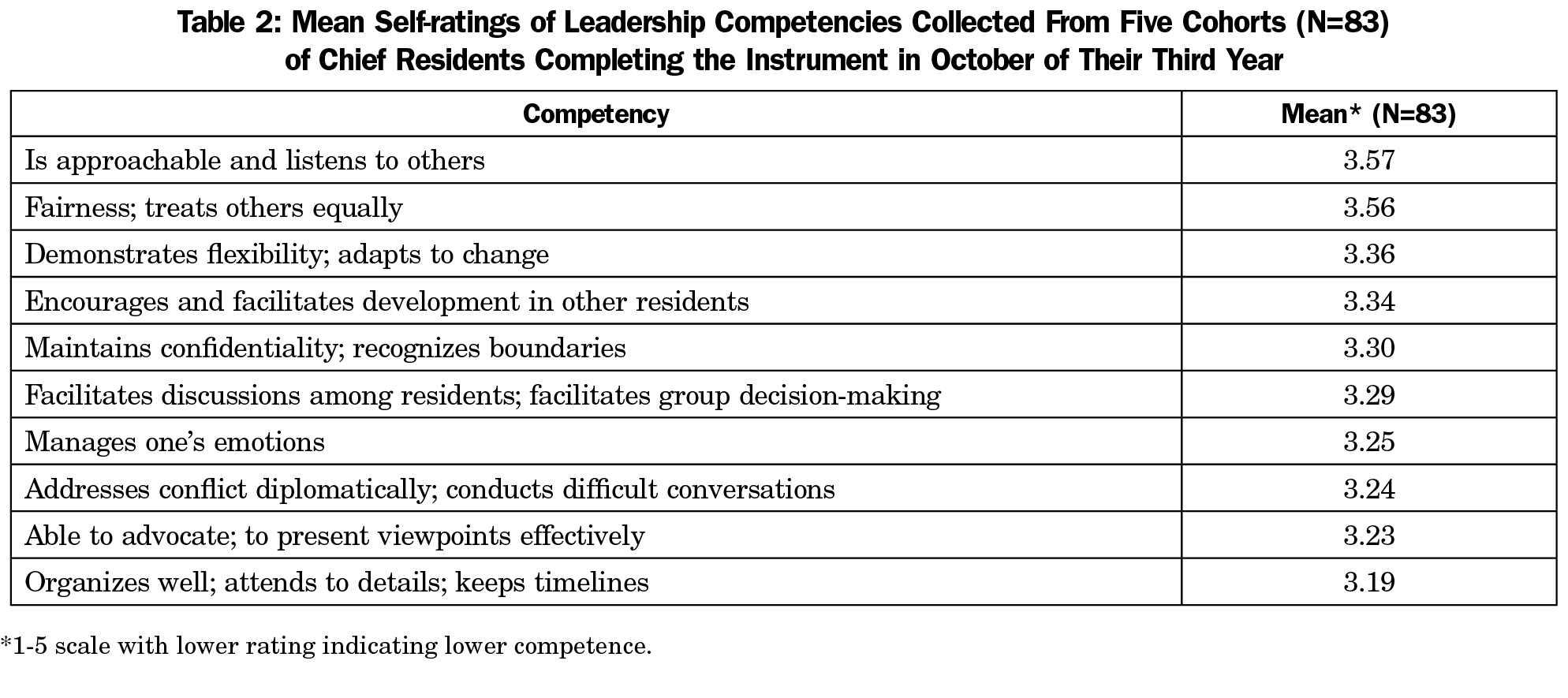

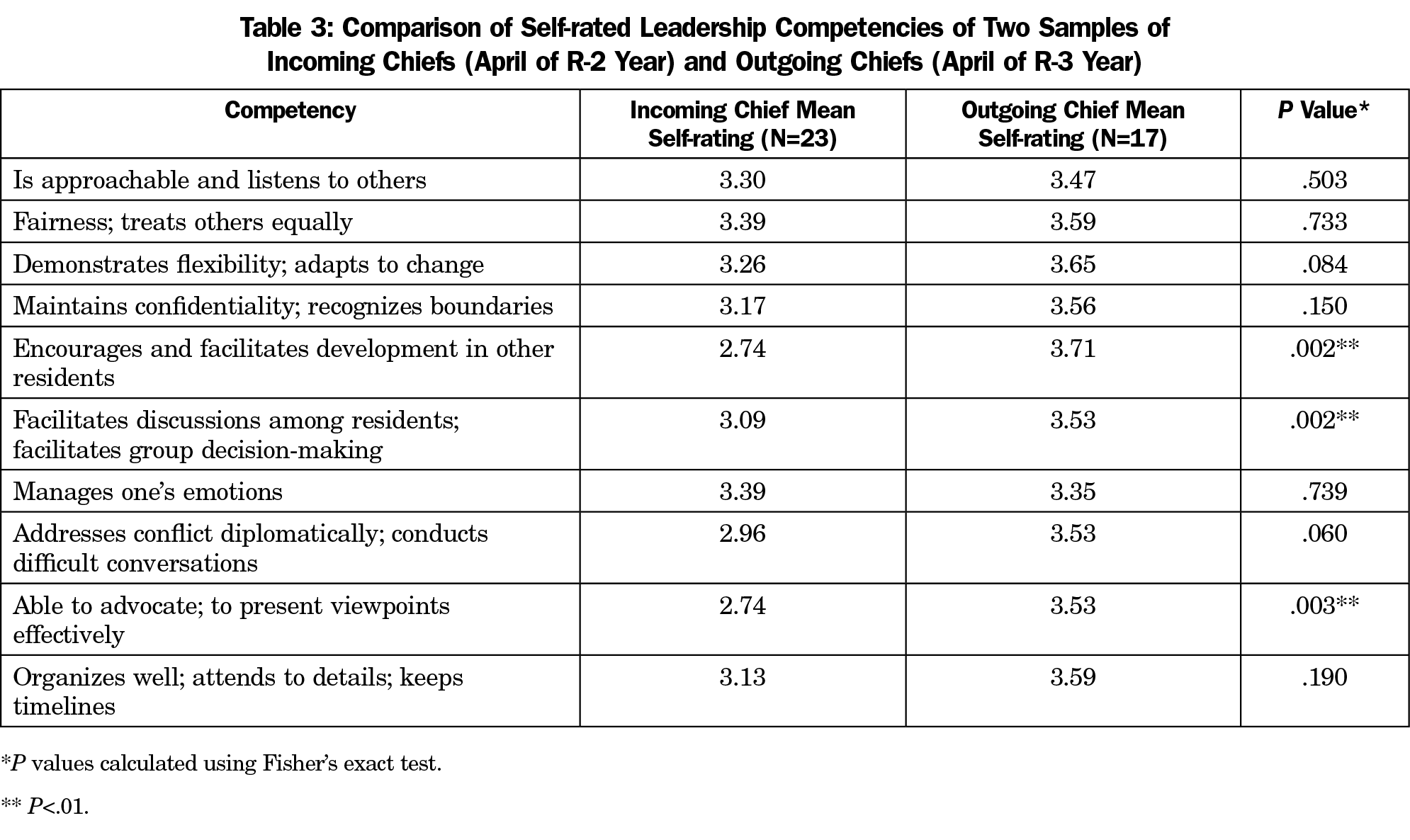

Results: The self-assessment instrument was completed by 83 chief residents over 5 years. Mean ratings range from 3.19 to 3.57 on a 5-point scale (low to high competency). The self-ratings of residents starting their chief year compared to residents at the end of their chief year showed an increase in 9 of the 10 competencies.

Conclusions: The leadership competencies are a useful tool to identify training priorities and to help chief residents or other leaders within a residency program identify skills for further development.

Many family medicine residency programs provide some type of leadership training for chief residents that vary from the American Academy of Family Physicians’ Annual Conference to local workshops, other state-sponsored or regional workshops, or training by faculty and outgoing chiefs.1,2 Although chief leadership training in family medicine and other specialties3-7 have common skill development elements such as conflict resolution and giving feedback, opinions differ about the role of chief residents8 and there are no standardized or clear leadership competencies chief residents must develop and demonstrate to be successful in their role.

The purpose of this study was to identify specific leadership skills for chief residents and develop a self-assessment tool to assess leadership strengths, weaknesses, and teaching priorities.

Description of Program

Colorado’s family medicine residency programs all participate in the Colorado Association of Family Medicine Residencies. Twice a year the association offers a day-long chief resident leadership workshop. Chief residents from 10 family medicine residencies participate. The fall workshop is attended by 15 to 20 third-year chief residents. Attendance at the spring workshop averages 25 and includes incoming chiefs from each program and a few soon-to-graduate chiefs. The workshops are designed to provide a variety of learning activities. Presenters include residency faculty and program directors from the residency network.

For the last 5 years, leadership competencies have been used to identify and prioritize workshop topics and for chief residents to self-assess their leadership abilities. A 10-item self-assessment instrument is administered at the beginning of each workshop. Participants keep their individual results and are encouraged to share them with their advisor or program director to continue their leadership development at their residency program. An anonymous copy of each resident’s response is kept by the trainers to identify specific competencies to be prioritized at the next workshop. Typically, three to four topics are presented at each day-long workshop. Priority is given to the lowest-rated competencies derived from the self-assessments completed at the previous workshop.

Development of the Leadership Competencies and Self-assessment Tool

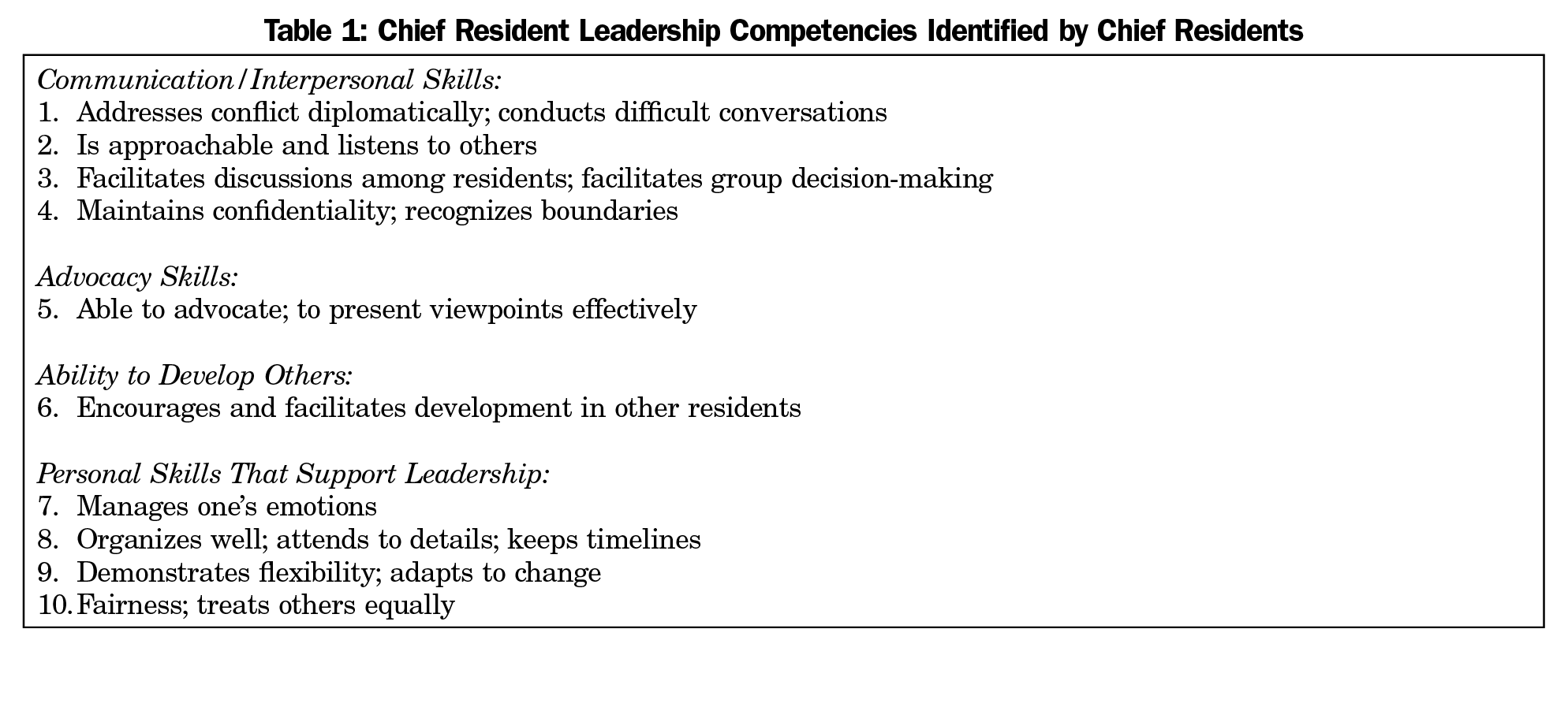

The chief resident leadership competencies were identified during the fall 2012 training workshop. Twenty-seven chief residents from 10 residency programs were divided into 5 focus groups. Group assignment was done by the workshop director (M.K.M.) to ensure chief residents from the same program were in different groups. Each group was asked to generate a list of skills needed for a chief to be successful. Next, responses from each focus group were shared verbally and written on a flip chart as a single, collective list. Finally, during a group discussion led by the workshop director, all participants helped to identify themes which were grouped into 10 competencies (Table 1).

Immediately following the workshop, the director developed the self-assessment tool. Minor edits were made to standardize the length of the competency descriptions. Word anchors on a 1-5 scale were created for each competency. The self-assessment instrument is shown in the Appendix (http://www.stfm.org/Portals/49/Documents/FMAppendix/Marvel-Appendix-FM2018.pdf).

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Colorado Health exempted this study from formal review.

Eighty-three family medicine chief residents completed the self-assessment over a 5-year period. The self-assessments were completed at the midpoint (October) of their chief year. The mean self-ratings on the 10 leadership competencies are shown in Table 2. The order of ratings has varied from one workshop to the next.

During the spring workshop in 2016 and 2017, the self-rating form was modified to enable a comparison of self-ratings of incoming vs outgoing chief residents. For this subset of 40 of the 83 chief residents, we were able to compare the self-ratings of residents starting their chief role (N=23) with residents at the end of their chief year (N=17; ratings of eight chiefs were omitted due to incomplete responses). Residents completing their chief year showed higher self-ratings in 9 of the 10 competencies (Table 3). Because the self-ratings were anonymous, it was not possible to compare the same residents across time.

This project resulted in competencies used for development of individual leadership goals as well as content planning for regional chief resident leadership workshops. The content of one workshop to the next varied based on the lowest-rated competencies from the previous session. The self-assessment instrument was easy to administer and score, typically taking 10 minutes. The behavioral descriptions of the competencies allow for concrete goal setting.

The competency self-ratings demonstrate that participants came into the program with an average to above-average rating in all key content areas. The higher self-ratings by more experienced outgoing chief residents were expected, and suggest the instrument contains core content that improves as leadership experiences expand. Many of the lower-rated competencies, such as addressing conflict, are not surprising because they continue to be challenges among more experienced leaders, as evidenced by the popularity of books such as Crucial Conversations.9

These results can help others develop a chief resident leadership curriculum. The entire list of competencies can be used, or the training can focus on the lowest self-assessment scores. These results can also help those mentoring chief residents to set individual goals and identify learning and growth priorities. Finally, these competencies can be used to inform a general leadership curriculum within residency programs.

There are several limitations to this project. The leadership competencies were developed in one setting by one group of chief residents and the workshop director. Important competencies may have been missed. The list of competencies could have been more robust by gathering input from program directors and faculty, as well as integrating results from chief training literature. Although the content of the workshops focused on the competencies, improvements in self-ratings may have been due to other factors, such as time or experiences as a chief resident. Additionally, the sample of chief residents was relatively small in size and lacks diversity. This tool was created and measured in only one state with relatively little ethnic or racial diversity. Finally, our research was conducted within a network of residency programs with two day-long workshops over the course of the chief resident year. It is unclear whether these competencies and results could be readily translated into single residency programs or different formats.

Chief resident leadership competence is important for the internal functioning of a residency program as well as development of future leaders in medicine.2 We encourage the use of these leadership competencies for training purposes and to conduct further research, such as using the assessment tool with a more diverse training group or converting the instrument into a 360 assessment tool.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the October 2012 workshop participants who contributed their ideas of core competencies for chief residents.

Presentations: Portions of this article were presented at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine’s 50th Annual Spring Conference, San Diego, CA, May 6, 2017.

References

- Mygdal WK, Monteiro M, Hitchcock M, Featherston W, Conard S. Outcomes of the first family practice chief resident leadership conference. Fam Med. 1991;23(4):308-310.

- Deane K, Ringdahl E. The family medicine chief resident: a national survey of leadership development. Fam Med. 2012;44(2):117-120.

- Farver CF, Smalling S, Stoller JK. Developing leadership competencies among medical trainees: five-year experience at the Cleveland Clinic with a chief residents’ training course. Australas Psychiatry. 2016;24(5):499-505. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856216632396

- Doughty RA, Williams PD, Brigham TP, Seashore C. Experiential leadership training for pediatric chief residents: impact on individuals and organizations. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(2):300-305. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-02-02-30

- Schwartz BJ, Blackmore MA, Weiss A. The Tarrytown chief residents leadership conference: A long-term follow-up. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(1):15-18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-013-0016-4

- Levine SA, Chao SH, Brett B, et al. Chief resident immersion training in the care of older adults: an innovative interspecialty education and leadership intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(6):1140-1145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01710.x

- Luciano G, Blanchard R, Hinchey K. Building chief residents’ leadership skills. Med Educ. 2013;47(5):524. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12194

- Norris T, Susman J, Gilbert C. Do program directors and their chief residents view the role of chief resident similarly? Fam Med. 1996;28(5):343-345.

- Patterson K, Grenny J, McMillan R, Switzler A. Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When the Stakes are High. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

There are no comments for this article.