Background and Objectives: Rural health disparities are growing, and medical schools and residency programs need new approaches to encourage learners to enter and stay in rural practice. Top correlates of rural practice are rural upbringing and rurally located training, yet preparation for rural practice plays a role. The authors sought to explore how selected programs develop learners’ competencies associated with rural placement and retention: rural life, community engagement, and community leadership.

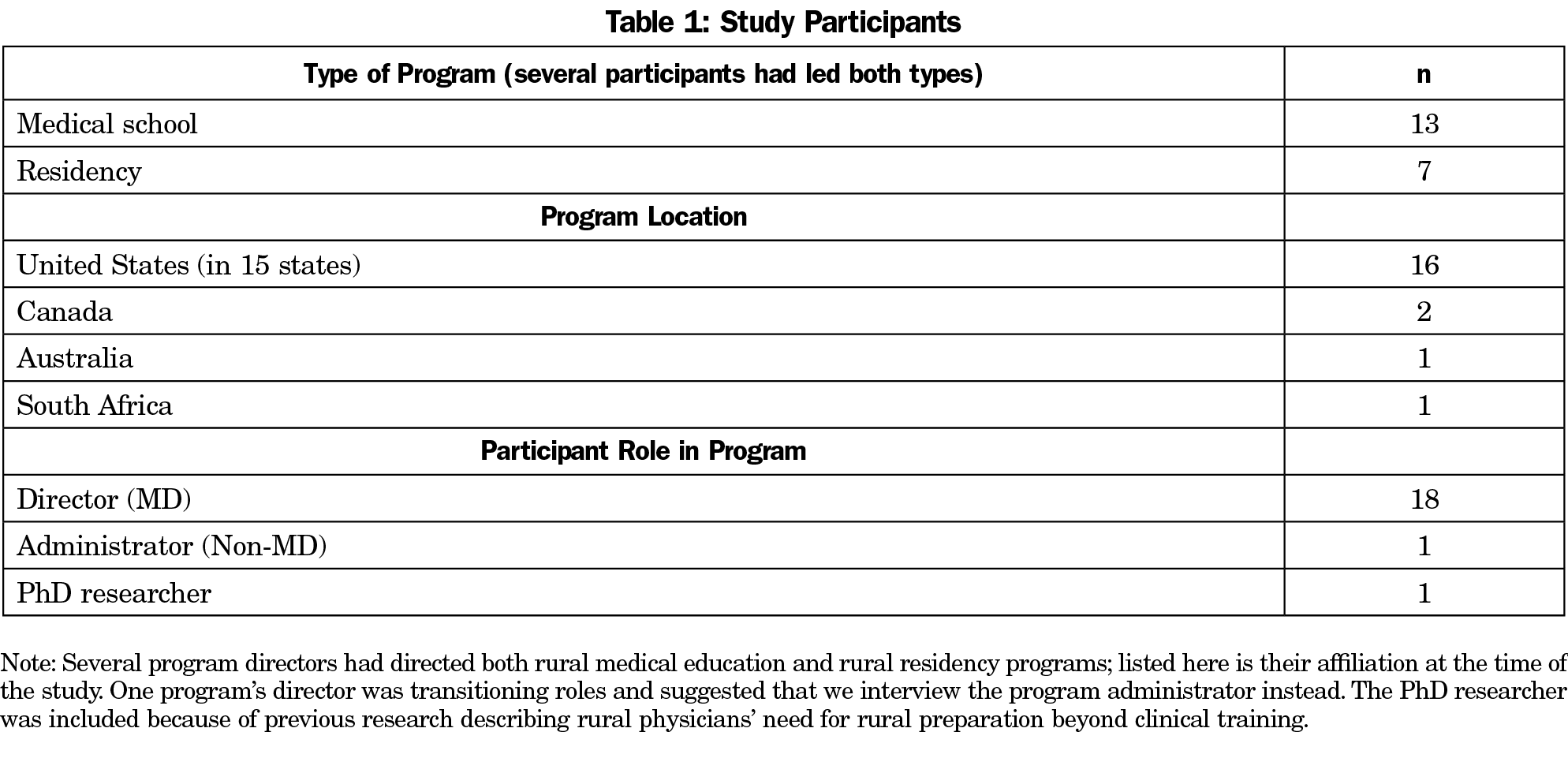

Methods: Qualitative, semistructured phone interviews (n=20) were conducted with faculty of medical schools or family medicine residencies across the United States, Canada, Australia, and South Africa in which success in training rural practitioners was identified in the literature or by leaders of the National Rural Health Association’s Rural Medical Educators Group. Participants included 18 physician program directors, one nonphysician program administrator, and one PhD researcher who had studied rural preparation. Interview transcripts were read twice using an inductive process: first to identify themes, and then to identify specific strategies and quotes to exemplify each theme.

Results: Participants’ recommendations for rural preparation were: (1) Be intentional about strategies to prepare learners for rural practice; (2) Identify and cultivate rural interest; (3) Develop confidence and competence to meet rural community needs; (4) Teach skills in negotiating dual relationships, leading, and improving community health; and (5) Fully engage rural host communities throughout the training process.

Conclusions: Medical schools and residencies may increase the likelihood of producing rural physicians by implementing these experts’ strategies. Educators may select strategies that mesh with the structure and location of their training program.

Health is now poorer in rural communities than in urban and suburban communities.1,2 New strategies are needed to address the persistent shortage of primary care physicians in rural communities throughout the United States.3 The literature has described several factors that impact whether physicians go into rural practice, including rural upbringing,4 length of training in a rural environment,4 financial incentives,5,6 whether providers identify as rural physicians,4,7-9 and also how prepared physicians are for rural living and rural leadership.10 While the top predictors of a rural medical practice are rural upbringing and rural training, few medical school applicants have rural backgrounds11; 50%-74% of practicing rural physicians were not raised in rural areas.12-19 Rural training track residencies succeed in producing rural physicians but are small and train few residents.20 In this study, we sought to better understand strategies that could be used broadly by training programs to cultivate rural interest among learners and prepare them to enter and remain in rural practice.

Studies show important factors for rural practice recruitment and retention include understanding rural life,10 engaging communities,4,21-28 and demonstrating community leadership,29 yet physicians report feeling unprepared for some of these aspects of rural practice.30 Longenecker et al recently explored eight domains of competence physicians need to work in rural communities and advocated that they be considered in curricular design: adaptability, living with scarcity and limits, resilience, integrity, reflective practice, collaboration, comprehensiveness, and agency/courage. In this study we sought to explore how and to what extent medical schools and residencies with success in producing rural physicians prepare learners for rural life independent of the clinical skills needed for rural practice.

We conducted qualitative, semi-structured phone interviews with one faculty member from each of 20 medical schools and family medicine residencies across the United States, Canada, Australia, and South Africa; 18 physician program directors; one nonphysician program administrator (when the program director was not available); and one PhD researcher who had published on the subject of rural preparation (Table 1). We selected this a priori list of institutions based on their track records producing rural physicians as identified in the literature31 or by leaders in the National Rural Health Association’s Rural Medical Educators Group. Interviewees were invited to participate via email. Two interviewers (S.T. ,C.C.) conducted phone interviews using an 11-question interview guide during July to November 2016; interviews lasted 25-45 minutes each. The interview guide (Table 2) was reviewed by a rural physician and pilot tested with one rural residency director, whose responses were included in the study.Verbal consent was obtained, and the conversations were recorded then transcribed verbatim. Transcriptions were read twice (S.T., M.C., A.B.P.A.) using an inductive process, first to identify themes, and then to identify specific strategies and quotes to exemplify each theme. All themes were discussed among authors until reaching consensus. The Mission Hospital Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Collectively, participants offered 24 recommendations for how medical schools and residencies can help learners prepare for rural life. Participants’ recommendations and examples are shown in Table 3. The recommendations fall into five thematic categories: (1) Be intentional about strategies to prepare learners for rural practice; (2) Identify and cultivate rural interest; (3) Develop confidence and competence to meet rural community needs; (4) Teach skills in negotiating dual relationships, leading, and improving community health problems; and (5) Fully engage rural host communities throughout the training process.

Be Intentional

Programs teaching learners need to be intentional in their rural preparation for learners. Study participants in more urban settings or communities that had grown over time tended to be more explicit about rural preparation. One participant explained:

As [the population of] this community has grown, we’ve lost some of the rural-ness. So last summer we identified a set of core values that make a doctor successful in a rural community which we emphasize in our resident recruitment and training. First, be community-centered: whatever the size of your community, you need to be out in it, figuring out what’s happening in your patients’ lives outside of the office. Second, provide full-spectrum care: care for your patients at nursing homes, community health centers, and schools, not just the office. Third, lead and advocate: our residents participate in community activities and hospital leadership committees. Fourth, be dynamic: you need to constantly evolve to meet the needs of the community. Fifth, care for vulnerable populations: those are the people who need you the most.

More rural medical schools and residencies had built rural exposure into the design of the program and had learners self-selecting for rural medicine, so their preparation of learners for rural life tended to be less explicit—“It just happens organically… living here for 1-3 years, the conversations schedule themselves.”

Identify and Cultivate Rural Interest

Many participants emphasized the best predictor of rural practice was rural upbringing, and it was a key admission criterion. Yet they acknowledged that some urban-raised physicians went into rural practice and stayed, which suggests giving everyone exposure to rural practice—casting a wide net—can cultivate more future rural practitioners. An urban-raised participant said:

I shouldn’t have been a rural doc. I do not fit any of the criteria. There are those who don’t fit the mold who wind up doing things as well as those who do fit the mold who don’t wind up going [rural]. You need to have programs and experiences for students to find their way.

One participant said selecting rural-raised and/or rural-interest learners was the single most important factor in their success producing rural physicians, stating “Well I’d love to tell you it was us [the program], but I think it’s them [the learners]. It’s who you recruit.” Participants described the importance of bringing rural-interest learners together regularly for camaraderie and to highlight the value of rural primary care careers. Several warned that because medical learners’ interests evolved over time, requiring a commitment to rural practice too early in training did not work.

Develop Confidence and Competence to Meet Rural Community Needs

Confidence and competence are developed through exposure in rural settings and skill building in rural competencies. Rural physicians operate with fewer resources and referral options than urban counterparts. Some participants said this required special characteristics of resilience and “tolerance of ambiguity”; others said such characteristics could be cultivated by longitudinal experiences. Participants described the need to develop confidence and competence in skills, as well as recognize one’s limits in a rural environment:

Out here I tell [the residents] you have to know when you’re two steps away from what you can’t do, because when you’re one step away, you better be figuring out where that patient has to go next so you’re not transferring an unstable patient.

Several participants discussed the challenge of teaching a scope of practice broader than was practiced by physicians in their rural regions:

If you train people enough in breadth and scope of practice, they will no longer fit in that community. If they do primary c-sections, and they’re not allowed to have that privilege where you trained them, they have to go even more rural. And I want to retain them [here].

Physicians’ skills need to match community needs, and if the skill set exceeds the capabilities of the community, one participant argued rural physicians need to be prepared to advocate for changes to the systems in which they work. Another argued that physicians need to expect to adapt their clinical practice to meet community need.

Teach Skills in Negotiating Dual Relationships, Leading, and Improving Community Health Problems

Participants emphasized the importance of learners living in and exploring rural communities during their training: “The number one preparation for rural life is plugging in and living here.” One program paid residents a bonus for living in the same community as the rural training site throughout their residency (instead of commuting from a nearby larger town). By spending extended time in a small town, learners have to face the real-life issues of setting boundaries in rural practice. Even those with rural backgrounds need to prepare for the confidentiality issues that arise for a small town doctor who knows “who’s sleeping with who, who has STDs, who is addicted to drugs… and how you interact with these patients when you see them in the restaurant.” Furthermore, learners and their families need to be prepared to live in a fishbowl, where “everyone is looking at everything you do and talking about it… what you’re buying at the grocery store… whether you drink alcohol at the restaurant.”

When properly prepared for the challenges of small town relationships, learners can appreciate more readily the benefits of rural practice, “the power and intimacy of enduring relationships with patients, staff, and the community.”

Many participants stressed the importance of involving learners in leadership activities, ie, serving on hospital committees and undertaking community projects. These activities allow the physician to impact the health and well-being of the community at a deeper and broader level, in a way that goes beyond individual patient care. One participant explained:

You need to have leadership skills not just because you’re going to be a doctor in practice, but because people are going to want you to sit on city council or the board of education… Graduates in rural areas may be the most qualified leaders on a lot of levels… We teach [our residents] it can be great to have a lot of venues where they have influence.

Leadership skills taught included advocacy, public speaking, and being an effective team member.

Most programs assigned projects that helped learners investigate community-wide health needs, get to know organizations addressing those needs, and plan their own intervention to improve community health. A participant explained:

It teaches [our students] that the physicians have to care for the community, and there are multiple ways to do so, and that is just part of their responsibility.

Fully Engage Rural Host Communities Throughout the Training Process

Participants emphasized the importance of local physicians and community members investing in the learners and their futures. In some programs, community members were central to many aspects of learner education:

We get the community involved in the major decisions… [such as] the selection process of the students. The students know and respect that. That creates a different power balance right from the word go.

One director described how his program cultivated relationships over time:

The communities bend over backwards to get the students a good experience. [To get to that point] campus faculty has to spend a lot of time just being there, developing relationships... Whenever we do anything in the community, we ask, ‘What does the community get out of this? What do we get? What do we have to give the community? What does the community give?’

By cultivating relationships in the rural communities that train learners, faculty help build community ownership of learners’ positive training experiences and future rural practices.

Based on interviews with faculty from training programs that have successfully placed physicians in rural communities, there are a number of strategies that other programs may implement to maximize the likelihood that learners cultivate a rural physician identity and seek out and remain in rural practice. The literature identifies which topics are important to address, and this study suggests some specific strategies for how to do so.

The limitations of our study include participants having been selected based on successful placement of rural physicians as identified through literature or by recognized leaders in rural health. There may be other programs preparing physicians for rural practice that we were not aware of (some programs may not track rural placement). In selecting training sites, we made no attempt to ensure a representative sample. Further, we examined medical schools and residencies together because we sought essential elements that could be distributed across a longer training period. However, because learners may need different interventions at different points of their training, and medical schools and residencies have different governing bodies dictating curriculum, they may have to select and apply strategies differently. For example, medical schools may focus on fostering rural identity through affinity groups, while residencies may emphasize building practice management and community health leadership skills. This study sought to capture the breadth of possible strategies rather than the rank importance of strategies, so frequency of each response was not measured.

Increasing the supply of rural physicians is important given the state of health in rural America. To do so, more programs need to commit to recruiting and training learners for rural practice and test these various strategies. While there are many factors that influence the supply of rural physicians, we focused on what training programs can do. Further studies should identify which individual or combination of strategies are most effective, and what key milestones during medical school and residency can be linked to requisite skills and competencies specific to rural practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Christa Currie for interviewing study participants and Bayla Ostrach, PhD and Lee Stevens for their editorial assistance on drafts.

Presentations: Thach S, Parlier AB, Currie C, Galvin SL. Preparing learners for rural medical practice: 15 Tips. Poster presentation at National Rural Health Association Annual Conference, San Diego, CA, May 10-12, 2017.

References

- Stein EM, Gennuso KP, Ugboaja DC, Remington PL. The epidemic of despair among white Americans: trends in the leading causes of premature death, 1999-2015. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(10):1541-1547. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.303941

- Adamy J, Overberg P. Rural America is the new ‘inner city’. Wall Street Journal. May 26, 2017. https://www.wsj.com/articles/rural-america-is-the-new-inner-city-1495817008. Accessed September 26, 2017.

- The family physician workforce: the special case of rural populations. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(1):147.

- Parlier AB, Galvin SL, Thach S, Kruidenier D, Fagan EB. The road to rural primary care: A narrative review of factors that help develop, recruit, and retain rural primary care physicians. Acad Med. 2018;93(1):130-140. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001839

- Duffrin C, Diaz S, Cashion M, Watson R, Cummings D, Jackson N. Factors associated with placement of rural primary care physicians in North Carolina. South Med J. 2014;107(11):728-733. https://doi.org/10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000196

- Li J, Scott A, McGrail M, Humphreys J, Witt J. Retaining rural doctors: doctors’ preferences for rural medical workforce incentives. Soc Sci Med. 2014;121:56-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.053

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1446-1451. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427

- Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt DD, Regehr G. Competency is not enough: integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1185-1190. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182604968

- Wald HS. Professional identity (trans)formation in medical education: reflection, relationship, resilience. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):701-706. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000731

- Pathman DE, Steiner BD, Jones BD, Konrad TR. Preparing and retaining rural physicians through medical education. Acad Med. 1999;74(7):810-820. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199907000-00016

- Hensel JM, Shandling M, Redelmeier DA. Rural medical students at urban medical schools: too few and far between? Open Med. 2007;1(1):e13-e17. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2801916/. Accessed September 26, 2017.

- Rourke JT, Incitti F, Rourke LL, Kennard M. Relationship between practice location of Ontario family physicians and their rural background or amount of rural medical education experience. Can J Rural Med. 2005;10(4):231-240.

- Chan BT, Degani N, Crichton T, et al. Factors influencing family physicians to enter rural practice: does rural or urban background make a difference? Can Fam Physician. 2005;51:1246-1247.

- Brooks RG, Mardon R, Clawson A. The rural physician workforce in Florida: a survey of US- and foreign-born primary care physicians. J Rural Health. 2003;19(4):484-491. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2003.tb00586.x

- Fryer GE Jr, Stine C, Vojir C, Miller M. Predictors and profiles of rural versus urban family practice. Fam Med. 1997;29(2):115-118.

- Wilkinson D, Beilby JJ, Thompson DJ, Laven GA, Chamberlain NL, Laurence CO. Associations between rural background and where South Australian general practitioners work. Med J Aust. 2000;173(3):137-140.

- Easterbrook M, Godwin M, Wilson R, et al. Rural background and clinical rural rotations during medical training: effect on practice location. CMAJ. 1999;160(8):1159-1163.

- Stenger J, Cashman SB, Savageau JA. The primary care physician workforce in Massachusetts: implications for the workforce in rural, small town America. J Rural Health. 2008;24(4):375-383. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00184.x

- Potter JM. Characteristics of Alaskan family physicians as determinants of practice location. Alaska Med. 1995;37(2):49-52, 79.

- National Rural Health Association, American Academy of Family Physicians. Rural practice: graduate medical education for (position paper). Published July, 2008. Revised 2013. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/rural-practice.html. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Longenecker RL, Wendling A, Hollander-Rodriguez J, Bowling J, Schmitz D. Competence revisited in a rural context. Fam Med. 2018;50(1):28-36. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2018.712527

- Hays R, Wynd S, Veitch C, Crossland L. Getting the balance right? GPs who chose to stay in rural practice. Aust J Rural Health. 2003;11(4):193-198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2003.tb00535.x

- Cameron PJ, Este DC, Worthington CA. Professional, personal and community: 3 domains of physician retention in rural communities. Can J Rural Med. 2012;17(2):47-55.

- Auer K, Carson D. How can general practitioners establish ‘place attachment’ in Australia’s Northern Territory? Adjustment trumps adaptation. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10(4):1476. https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/1476. Accessed January 25, 2018.

- Hancock C, Steinbach A, Nesbitt TS, Adler SR, Auerswald CL. Why doctors choose small towns: a developmental model of rural physician recruitment and retention. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(9):1368-1376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.002

- Cutchin MP. Physician retention in rural communities: the perspective of experiential place integration. Health Place. 1997;3(1):25-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1353-8292(96)00033-0

- Cutchin MP. Community and self: concepts for rural physician integration and retention. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(11):1661-1674. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00275-4

- Cutchin MP, Norton JC, Quan MM, Bolt D, Hughes S, Lindeman B. To stay or not to stay: issues in rural primary care physician retention in eastern Kentucky. J Rural Health. 1994;10(4):273-278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.1994.tb00241.x

- Woloschuk W, Crutcher R, Szafran O. Preparedness for rural community leadership and its impact on practice location of family medicine graduates. Aust J Rural Health. 2005;13(1):3-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1854.2004.00637.x

- Whiteside C, Pope A, Mathias R. Identifying the need for curriculum change. When a rural training program needs reform. Can Fam Physician. 1997;43:1390-1394.

- Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Wortman JR. Medical school programs to increase the rural physician supply: a systematic review and projected impact of widespread replication. Acad Med. 2008;83(3):235-243. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318163789b

There are no comments for this article.