The practice of modern medical ethics is largely acute, episodic, fragmented, problem-focused, and institution-centered. Family medicine, in contrast, is built upon a relationship-based model of care that is accessible, comprehensive, continuous, contextual, community-focused and patient-centered. “Doing ethics” in the day-to-day practice of family medicine is therefore different from doing ethics in many other fields of medicine, emphasizing different strengths and exemplifying different values.

For family physicians, medical ethics is more than just problem solving. It requires reconciling ethical concepts with modern medicine and asking the principal medical ethics question—What, all things considered, should happen in this situation?—at every clinical encounter over the course of the patient-doctor relationship.

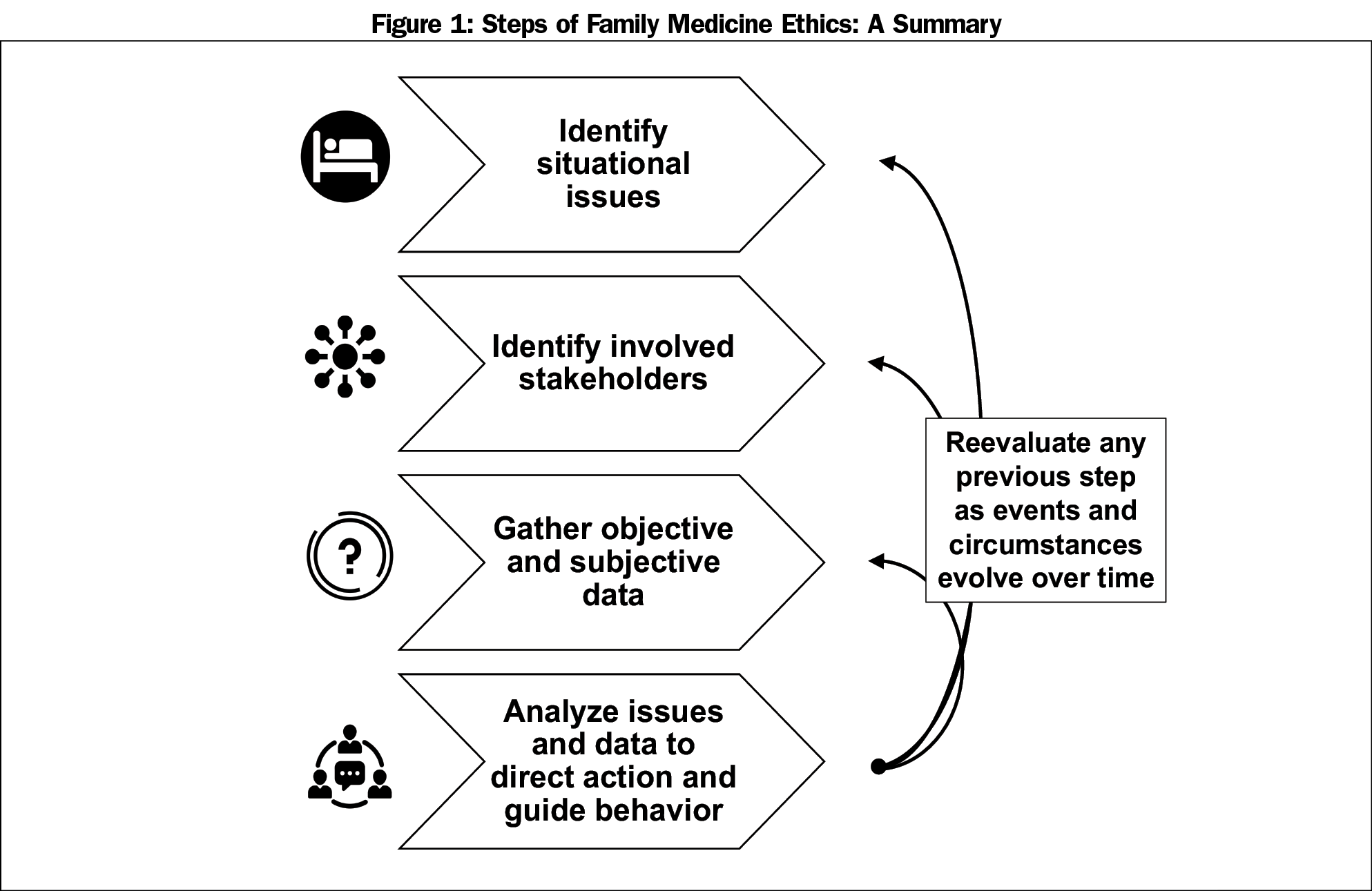

We assert that family medicine ethics is an integral part of family physicians’ day-to-day practice. We frame this approach with a four-step process modified from other ethical decision-making models: (1) Identify situational issues; (2) Identify involved stakeholders; (3) Gather objective and subjective data; and (4) Analyze issues and data to direct action and guide behavior. Next, we review several ethical theories commonly used for step four, highlighting the process of wide reflective equilibrium as a key integrative concept in family medicine. Finally, we suggest how to incorporate family medicine ethics in medical education and invite others to explore its use in teaching and practice.

The field of medical ethics has expanded exponentially over the past century.1,2 It developed as a response to the establishment of the duties of medical professionals and the rights of individual patients in the face of an explosion of medical technology and its application in practice.1,3 This has created a specialized expert approach to the practice of ethics that is largely acute, episodic, fragmented, problem-focused and institution-centered.

Family medicine has evolved over the past 50 years in response to society’s need for more and better-trained primary care physicians and to balance medicine’s otherwise specialized, highly technologic growth.3-6 It is built upon a relationship-based model of care that is accessible, comprehensive, continuous, contextual, community-focused and patient-centered.4,7-9 “Doing ethics” in the day-to-day practice of family medicine is therefore different from doing ethics in many other fields of medicine, emphasizing different strengths and exemplifying different values.

Family physicians are holistic, generalist experts with a breadth of medical knowledge and skills who focus on people with concerns, not just on biomedical problems to be solved.10,11 The practice of contemporary family medicine requires reconciling ethical concepts with modern medical science and asking the principal medical ethics question—What, all things considered, should happen in this situation?—at every clinical encounter over the course of the patient-doctor relationship.10

To help answer this question in light of this historical background, and based on our own observations and reflections, our purposes here are: (1) to take a broad look at how clinical ethics is currently taught and practiced, and (2) to propose a family medicine approach to ethics that integrates theory, decision-making and person-centered care in an easily accessible manner. We hope this review will inform clinical ethics education and help busy family physicians reflect upon, address, and resolve ethics issues with grace, dignity, and equanimity.

Developing a Family Medicine Ethics

Traditional Perspectives

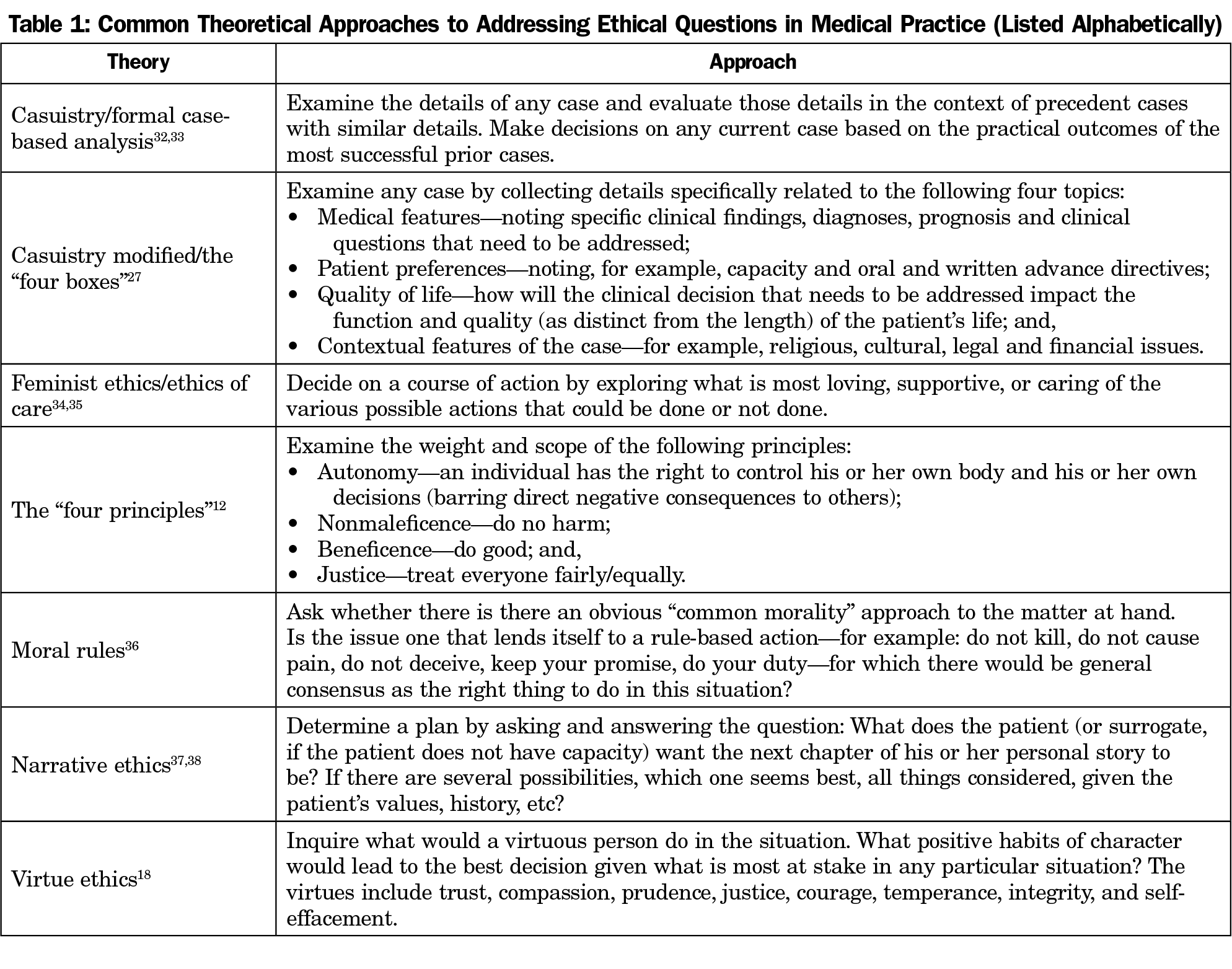

For the past few decades, nearly all physicians in the United States have received some medical ethics education. Commonly, this includes a review of the “four principles,” an introduction to rules of confidentiality and informed consent, and a discussion of key topics such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation and advance care planning.12-15 Many clinicians see ethics solely through the framework of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice (Table 1).

Recently, ethicists have begun to teach medical students and resident physicians about professionalism, identified as one of the six core competencies of medical education and practice.16,17 Some have reintroduced virtue ethics as a way to promote positive behaviors related to reporting medical errors, responding to professional misconduct, documenting in electronic health records, and preparing for board examinations (Table 1).18-20

Unfortunately, few contemporary scholars have discussed how to become an ethically-aware physician in day-to-day practice.19,21,22 The American Academy of Family Physicians Curriculum Guideline on Medical Ethics provides an excellent outline of clinical, professional and medico-legal topics, but it offers few specifics on how to integrate ethical thinking into routine care, let alone how to teach it.23 A 2014 review of family medicine residency programs notes considerable variation in both the content and delivery of ethics educations.24 In one exception to these observations, Truog and colleagues have introduced the concept of “micro” ethical decision-making as a structure for practice-based ethics.25 They address discrete issues such as how to provide patients medical information, including how much truth to tell in eliciting informed consent, how to respect patient values, and how to manage one’s own biases in clinical conversations.

Perspectives From Family Medicine

Our view, in contrast, is that—taken together—the many activities of family physicians’ assessing clinical presentations, ordering diagnostic tests, counseling and educating patients and families, writing prescriptions, performing procedures, and making referrals have a “macro” ethical effect on the medical care and health status of our patients and communities. Although an appreciation of principles and virtues is important, and learning how to respond to specific clinical, professional, and medico-legal situations is appropriate, they are not enough.

We see family medicine ethics as a combination of both problem-solving and the manner of how to act with patients generally and routinely, over time, helping us reflect upon our patient care and guiding our professional behavior and decision-making for issues large and small. Indeed, the word “ethics” comes from the Greek ethos, meaning custom or habit, and fits well with the family medicine values described above. Whereas ethical questions in relation to specific clinical quandaries may be consciously phrased to reflect a continuum between right or wrong and permissible or not permissible, family medicine ethics may also be thought of as how family physicians habitually consider and evaluate concepts of better and worse in our day-to-day activities.

Steps in Family Medicine Ethics

Family medicine ethics begins with a four-step process modified from several models of ethical decision-making (Figure 1).26-28 With practice, we believe these steps will build trust and confidence and lead to better outcomes, greater satisfaction, and improved well-being among both patients and physicians. The first step is identifying what issues, concerns, and questions appear to be at play in the situation at hand. Sometimes, these circumstances present as conflicts. Other times, they are simply circumstances that need to be clarified. Almost always, they need to be reassessed as time goes on.

The second step is identifying the relational web of individuals involved in a situation—frequently called stakeholders—understanding how they are engaged, and gathering information from them.26-28 There are always more people personally affected by any particular situation than those at its center, even when they are not physically present. Sometimes, physicians and the medical care team themselves are stakeholders in a case. Asking and answering several questions—Who is involved? What is their relationship to the patient? What is at stake for them in the situation and issue at hand? Are they willing to participate in decision-making, if appropriate?—is the beginning to any further assessment and management.

The third step involves gathering objective and subjective data, understanding that both must be interpreted contextually, being considerate of both individual experience and social environment. Objective data include what people think of as hard facts, recognizing that these data are influenced by the perceptions and priorities of each stakeholder. Although an open-ended, probing approach can help when inquiring about objective data,29,30 their significance is often blurred by uncertainty. In such instances, explicit exploration of implicit assumptions is necessary. Subjective data include the information each stakeholder brings to the situation. More than just medical history, this data includes past experiences and personal stories, and the values, beliefs, and emotions associated with them.31 Factors that influence subjective data gathering include age, general education level, health literacy, communication abilities, and the personal relationships among all the stakeholders.

The fourth step is organizing and analyzing this information to develop possible plans of action for specific patients in particular situations. Although principles and virtues are helpful, there are other approaches to ethical analysis (Table 1). No single ethical theory is applicable in all situations, and the recommendations generated by one theory may conflict with those promoted by others when applied to real-life circumstances. This is not surprising, since the traditional goals of medicine39—to cure disease, to prevent illness and promote health, to treat pain, and to prolong life—often conflict with each other.

Incorporating a Wide Reflective Equilibrium

Because the different ethical theories outlined in step four may generate alternative actions for different ethical scenarios, we believe the practice called “wide reflective equilibrium”40-42 is most consistent with a family medicine approach to ethical analysis. This comprehensive process integrates various theoretical approaches by asking the question—Does the right thing to do ring true when examined by a preponderance of analytic methods, in the context at hand?—in order to make thoughtful, interdisciplinary assessments and management plans for patients.

We feel strongly about this integrative approach for two reasons. First, many clinical ethics scholars who advocate one theoretical approach have exposed the limitations of other approaches.32,43-45 Principles, for example, provide a sound foundation for examining abstract issues, but they are criticized for not being able to provide practical, specific solutions in real-life patient care. Case-based methods and narrative ethics provide rich contextual details, but their recommendations may be seen as too situational and rationally indefensible. Virtue ethics promotes positive professional behavior, but it too may be viewed as overly vague in many situations. Our experience is that using any one of these approaches alone does not provide clear guidance in common clinical scenarios such as addressing how much information to give about complex procedures, how to assess decision-making capacity in patients with behavioral or cognitive problems, or how to work with patients who prioritize the value of family over autonomy in end-of-life decision-making.

Second, as noted earlier, family physicians view patients as people with concerns, not simply as individuals with biomedical problems to be solved. Family doctors focus on the whole person—not on any one biochemical pathway, organ system, procedural skill, age, gender or time frame—and consider a variety of perspectives—physiological, psychological, social, environmental and existential—when formulating clinical management plans for patients. In family medicine, the best decisions are always those that hang together when viewed through the lens of several clinical approaches which assess the entirety of a patient’s situation. Similarly, family physicians have an obligation to consider and integrate the ethics of medical care and professional behavior from a variety of theoretical approaches to generate one comprehensive ethical management plan for particular patients in specific contexts.

We see family medicine ethics as the study of discerning the right thing to do and the right way to act, to the best of our abilities, in all of the clinical and professional situations we encounter. It is the application of our best thinking about right and wrong and better and worse to make real-life decisions that direct our actions and guide our behavior in day-to-day practice.

We observe that experienced family doctors often use a holistic clinical and moral informed intuition to guide both medical and ethical decision-making in today’s fast-paced health care environments.46-48 However, this intuition is only as good as its underlying foundations in medical science and ethical thinking. These foundations must be built during clinical training, when the integration of theory and practice is first learned, and must be attended to continuously throughout one’s career.

Ethical thinking is more than just a mix of faith, feelings, science and the law. It is more than just following one’s conscience. Ethics requires individuals to be mindful about their beliefs and values,31 and perhaps especially in family medicine, it requires us to maintain a sense of ethical humility about our knowledge, attitudes, and skills. Since we as family physicians are commonly our patients’ primary clinical and ethical decision-making resource, we have a responsibility to develop data-gathering and deliberative skills both in ourselves and in the patients, families, staff, and colleagues with whom we interact. In family medicine, as in other professional endeavors, ethical decision-making and ethical behavior do not just happen. They are learned, practiced, evaluated, and improved. The approach we have presented here is a good start.

We encourage future scholarship in family medicine ethics, using empirical research to investigate how family physicians think and act, as well as to understand patients’ and families’ points of view. Our experience is that education in ethical thinking is best delivered through a combination of focused readings and interactive scenario-based discussions for medical students and via facilitated self-reflection on current practice—using family physicians’ own cases—in graduate and continuing medical education. We believe these methods will promote an ethos of thinking critically about ethics in our day-to-day work. Others likely have experience with alternative teaching methods, and we invite creative innovation in this regard.

Further Considerations

Some readers may argue that what we describe as a family medicine ethics is no different from other approaches to the skillful practice of medical ethics—a thoughtful, complex, contextually-oriented, relationally-centered process that is informed, but not constrained, by abstract theories. Others may argue that good training in how to respond to common clinical scenarios is sufficient to know how to address common ethical, professional and medico-legal scenarios. Still others may fear that this approach requires formal ethical evaluation of all medical decisions, adding unwarranted time to every patient encounter.

We respond by noting that what distinguishes family medicine ethics from other approaches is not the detail of its content, but the broad, integrated, clinically-accessible manner in which it is practiced: a relationship-based, comprehensive, continuous, contextual, community-focused, patient-centered process that simultaneously integrates principles, virtues, cases, rules, narrative, and care with disease-based problem-solving, illness-oriented prevention, and future-focused health promotion. We further suggest that the most important attribute of being an excellent family physician is our ability to handle complexity, see the big picture, and think, rather than practice by algorithm in common clinical scenarios. Lastly, we do not want to imply that every case requires the structured approach presented here. We do, however, believe that every clinical encounter requires addressing the question: What, all things considered, should happen in this situation?

In family medicine, ethics is habitually remembering that people come to us for our knowledge, skills and judgment to do the right things, and to do those things right, for clinical issues large and small, in the moment at hand and with an eye on the future, given the resources available. The goal of family medicine ethics is to generate the best plans of action that lead to the best possible real-world outcomes, viewed from a preponderance of perspectives and linked to values shared with our patients. Its scope is broad, examining both medical problems to be solved and health issues to be explored, and its results emerge over time. We trust both patients and physicians will benefit from its wise and caring practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr David Satin for his critical review of the manuscript.

Presented, in part, at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Bioethics and Humanities, Washington DC, October 2016.

References

- Jonsen AR. A Short History of Medical Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000.

- Baker R. The American medical ethics revolution. In: Baker R, Caplan AL, Emanuel LL, Latham SR, eds. The American Medical Ethics Revolution. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1999:17-51.

- Porter R. The Cambridge History of Medicine. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

- McWhinney IR. A Textbook of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997.

- Starfield B. Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998.

- McWhinney IR. General practice as an academic discipline. Reflections after a visit to the United States. Lancet. 1966;1(7434):419-423. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(66)91412-7.

- Saultz JW. Textbook of Family Medcine. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000.

- Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston WW, McWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman TR. Patient-Centered Medicine: Transforming the Clinical Method. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995.

- Taylor RB, ed. Family Medicine: Principles and Practice. 6th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2003. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-21744-4.

- Brody H. The Healer’s Power. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1992.

- Tunzi M. Keeping time. Hastings Cent Rep. 2013;43(6):7-8. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.224.

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013.

- DuBois JM, Burkemper J. Ethics education in U.S. medical schools: a study of syllabi. Acad Med. 2002;77(5):432-437. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200205000-00019.

- Lehmann LS, Kasoff WS, Koch P, Federman DD. A survey of medical ethics education at U.S. and Canadian medical schools. Acad Med. 2004;79(7):682-689. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200407000-00015.

- Roberts LW, Geppert CM, Warner TD, Green Hammond KA, Lamberton LP. Bioethics principles, informed consent, and ethical care for special populations: curricular needs expressed by men and women physicians-in-training. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(5):440-450. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.46.5.440.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. CLER Pathways to Excellence: Expectations for an optimal clinical learning environment to achieve safe and high quality patient care. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/CLER/CLER_Brochure.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2017.

- The Joint Commission. Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals. Medical Staff Standard 06.01.03. January 2017.

- Pellegrino ED, Thomasma DC. The Virtues in Medical Practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993.

- Brody H, Doukas D. Professionalism: a framework to guide medical education. Med Educ. 2014;48(10):980-987. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12520.

- Karches KE, Sulmasy DP. Justice, courage, and truthfulness: virtues that medical trainees can and must learn. Fam Med. 2016;48(7):511-516.

- Carrese JA, Malek J, Watson K, et al. The essential role of medical ethics education in achieving professionalism: the Romanell Report. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):744-752. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000715.

- Carrese JA, McDonald EL, Moon M, et al. Everyday ethics in internal medicine resident clinic: an opportunity to teach. Med Educ. 2011;45(7):712-721. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.03931.x.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Recommended Curriculum Guidelines for Family Medicine Residents. Medical Ethics. 2013. AAFP Reprint No. 279.

- Manson HM, Satin D, Nelson V, Vadiveloo T. Ethics education in family medicine training in the United States: a national survey. Fam Med. 2014;46(1):28-35.

- Truog RD, Brown SD, Browning D, et al. Microethics: the ethics of everyday clinical practice. Hastings Cent Rep. 2015;45(1):11-17. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.413.

- Santa Clara University, Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. A Framework for Ethical Decision-Making. www.scu.edu/ethics/practicing/decision. Accessed June 30, 2017.

- Jonsen AR, Siegler M, Winslade WJ. Clinical Ethics: A Practical Approach to Ethical Decisions in Clinical Medicine. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2015.

- Berkowitz KA, Chanko BL, Foglia MB, Fox E, Powell T. Ethics Consultation: Responding to Ethics Questions in Health Care. 2nd ed. Veterans Health Administration, National Center for Ethics in Health Care; 2015. https://www.ethics.va.gov/docs/integratedethics/ec_primer_2nded_080515.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2017.

- Ventres WB. The Q-List manifesto: how to get things right in generalist medical practice. Fam Syst Health. 2015;33(1):5-13. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000100.

- Zaner RM. Medicine and dialogue. J Med Philos. 1990;15(3):303-325. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/15.3.303.

- Epstein RM, Street RL Jr. Shared mind: communication, decision making, and autonomy in serious illness. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(5):454-461. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1301.

- Jonsen AR. Casuistry: an alternative or complement to principles? Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 1995;5(3):237-251. https://doi.org/10.1353/ken.0.0016.

- Jonsen AR, Toulmin S. The Abuse of Casuistry. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1998.

- Tong R. The ethics of care: a feminist virtue ethics of care for healthcare practitioners. J Med Philos. 1998;23(2):131-152. https://doi.org/10.1076/jmep.23.2.131.8921.

- Carse AL. The ‘voice of care’: implications for bioethical education. J Med Philos. 1991;16(1):5-28. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/16.1.5.

- Gert B, Culver CM, Clouser KD. Bioethics: A Systematic Approach. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. https://doi.org/10.1093/0195159063.001.0001.

- Brody H. The four principles and narrative ethics. In: Gillon R, ed. Principles of Health Care Ethics. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 1994:207-215.

- Charon R, Montello M. Stories Matter: The Role of Narrative in Medical Ethics. New York: Routledge; 2002.

- Callahan D. The goals of medicine. Setting new priorities. Hastings Cent Rep. 1996;26(6):S1-S27. https://doi.org/10.2307/3528765.

- Daniels N. Justice and Justification: Reflective Equilibrium in Theory and Practice. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1996. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511624988.

- Kuczewski M. Casuistry and principlism: the convergence of method in biomedical ethics. Theor Med Bioeth. 1998;19(6):509-524. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009904125910.

- Tunzi M. Ethical theories and clinical practice. One family physician’s approach. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8(4):342-344. https://doi.org/10.1001/archfami.8.4.342.

- Strong C. Theoretical and practical problems with wide reflective equilibrium in bioethics. Theor Med Bioeth. 2010;31(2):123-140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11017-010-9140-2.

- Rawls J. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1971.

- Clouser KD, Gert B. A critique of principlism. J Med Philos. 1990;15(2):219-236. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/15.2.219.

- Leffel GM, Oakes Mueller RA, Curlin FA, Yoon JD. Relevance of the rationalist-intuitionist debate for ethics and professionalism in medical education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2015;20(5):1371-1383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-014-9563-z.

- Braude HD. Human all too human reasoning: comparing clinical and phenomenological intuition. J Med Philos. 2013;38(2):173-189.

- Tilburt JC, James KM, Jenkins SM, Antiel RM, Curlin FA, Rasinski KA. Righteous minds in health care: measurement and value of social intuition in accounting for the moral judgments in a simple of US physicians. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e75379. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073379.

There are no comments for this article.