In my day-to-day work, annoying frustrations are common. Simple glitches in managing the electronic health record, financial pressures that threaten quality, and an informal curriculum that maligns my chosen discipline occasionally put me at risk of becoming discouraged. Sometimes, they build to a point where my focus of attention shifts to the burdens of being a clinician-educator in family medicine rather than its satisfactions.

That is why I am now grateful to the authors, editors, and STFM leaders who have made the recent dedicated issue of Family Medicine possible. Their contributions have helped me refocus my attention on values I have long believed to be central to my professional identity. Their dedication has inspired me to remember why I chose to do this work in the first place.

Fundamentally, the articles in this issue—and the disparities in the United States they discuss—are about racism.1-3 Of concern is well over 400 years of injustice, including both the existence of black African slaves in North America and our country’s collective inability to deal with this history and its reverberations over time.

Issues of power, class, money, and the various political and economic ideologies that infuse our national consciousness also obviously contribute to discussions on racism. From a bio-psycho-eco-social viewpoint, anxiety, fear, and insecurity in the face of the “other”—anyone who might look, think, or act in ways that appear to threaten our sense of integrity as human beings—also play critical roles. I state this as an aging, Caucasian male from Minnesota, now making my way in Arkansas. I honestly believe these points of view apply universally to each of us, albeit from radically different perspectives depending on which side of the societal and emotional divide one sees him or herself.

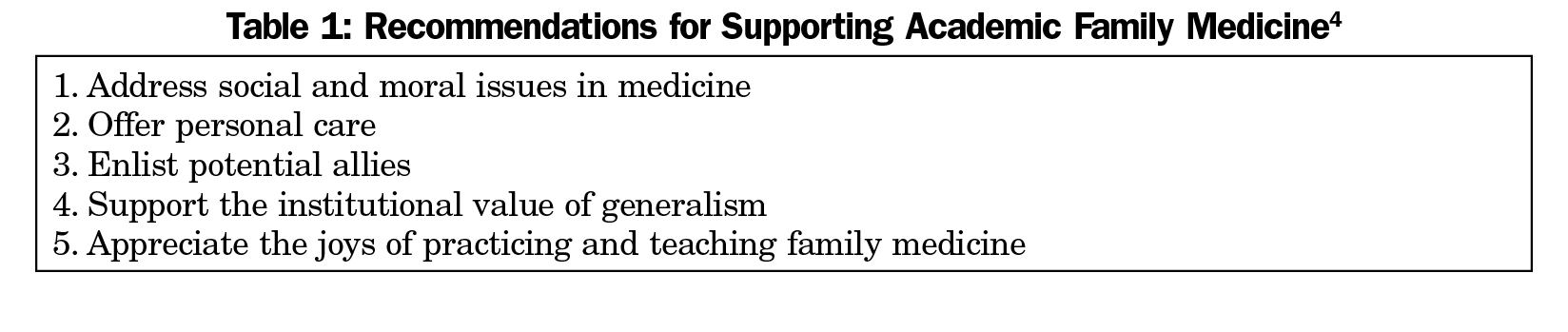

As many of the articles point out, a social justice orientation is key to addressing these issues. In fact, a distinguished outsider to our discipline—Steven Schroeder, MD, former President and CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation—recently wrote that social justice forms the moral core of family medicine.4 To his five recommendations for reinforcing that core and the importance of family medicine (Table 1), however, I add one more.

We as family physician educators must nurture our signature presence as healers5—working individually with patients and collectively through community engagement—toward the reconciliation of past and present injustices, the recognition of our interdependency with others, and the acknowledgment of fear in the face of suffering. We must do this in our daily work, modeling our intentions to both the patients we care for and the new generations of physicians we train. We must also do this in other important venues where policies are shaped, as visionaries, advocates, and administrators, over the long haul of our careers.

Reading the articles in January’s Family Medicine, all dedicated to disparities in health outcomes, I felt proud to be a family physician and a member of STFM.

There are no comments for this article.