Background and Objectives: Only about one-third of adult Americans have completed advance directives for end-of-life care, and primary care physicians report that they are not always comfortable discussing advance care planning (ACP) with patients. Current approaches to teaching clinicians about ACP have limited evidence of effectiveness. With the objective of improving residents’ comfort and skill discussing ACP with patients, we developed a curriculum that involved clinicians and attorneys working together to teach first-year family medicine residents (R1) about leading ACP discussions with patients.

Methods: Our curriculum consisted of a 1-hour multimedia training session on ACP followed by a series of direct in-exam room observations. Attorney and/or physician faculty observed residents holding ACP discussions with patients and provided structured feedback to residents about their performance. The initial R1 cohort observed had a series of three direct observations; the subsequent R1 cohort had two direct observations. We developed an evaluation tool with a 5-point developmental scale (beginner, novice, developing, near mastery, mastery) corresponding to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s milestone system to score residents’ performance.

Results: R1 performance improved from the beginner/novice level during the first observed ACP discussion to the novice/developing level during the second or third discussion, representing an increase in competence to that expected of a second- or early third-year resident.

Conclusion: Based on our initial experience, using medical-legal partnerships to teach residents about ACP may be more effective than previously reported approaches. Validation of our results with a larger sample is needed.

Only about one-third of American adults have advance directives for end-of-life care.1 There are many reasons for this, one of which is physician discomfort discussing advance care planning (ACP) with patients.2 Studies show that primary care residents often fail to undertake ACP discussions with patients, lack the confidence and skills to undertake them, and find them stressful.3,4 A 2016 meta-analysis found only low to very low evidence for the benefit of teaching about ACP through lectures or active learning activities such as small group discussions, role-play, or video/audio observation.5 New approaches are needed.

One potential approach is medical-legal partnerships (MLPs). These are collaborations between legal and health care professionals to address patients’ legal and social needs that affect health.6 Our family medicine department hired an attorney to develop our MLP, with three main goals: (1) to train residents on why and how to screen for and address social determinants of health such as housing and economic stability; (2) to raise residents’ awareness of legal issues faced by underserved or vulnerable populations, including older adults; and (3) to provide direct legal services to patients to address legal issues identified by patients’ clinicians. Today our MLP includes one full-time faculty attorney (who participated in the intervention described in this report) and one half-time attorney who works with clinicians in two of our department’s family medicine clinics.

Here, we describe our experience using our MLP to train first-year residents (R1s) to lead ACP discussions and evaluate the experience using parameters specific to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) family medicine training requirements.

The University of Arizona Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed the methods used for teaching and data collection and determined the project was not subject to IRB oversight.

Initial Program

The initial program was developed by an attorney and a family physician, both authors of this report. The attorney is the director of our MLP, and has worked in our clinic as a member of our residency faculty since 2005. The MLP’s medical director is a family physician (our residency program director).

As MLP leaders, the aforementioned individuals developed and administered the initial curriculum (a 1-hour session with several components), including providing residents with descriptions of ACP forms (powers of attorney, living wills, and directives declining resuscitation, etc). Handouts were provided to residents with tips about how to introduce ACP discussions. We also created multimedia presentations about factors to consider when selecting health care proxies, and the roles of patients, proxies, clinicians, and attorneys in these processes. In addition, we showed videos from the Education on Palliative and End-of-Life Care (EPEC) Project7 and an episode from the television program Seinfeld8 that comically demonstrated designating a proxy.

Residents completed presession and postsession questionnaires. Responses showed only small improvements in self-reported knowledge about and confidence in leading ACP discussions, and residents cited the need for additional training.

Expanded Program

Based on the feedback, we expanded ACP trainings with two major changes: (1) teaching about how to conduct values-based ACP discussions, and (2) faculty observation and evaluation of residents conducting ACP discussions. To accomplish the first change, we added videos demonstrating contrasting values in discussions about cardiopulmonary resuscitation,9 and handouts were expanded to include tips on eliciting patients’ values and goals for medical care. Sessions were facilitated by the MLP director and medical director.

The second change was to perform direct observations of residents leading ACP discussions with patients. Residents and/or faculty identified patients from the resident’s continuity panel with whom ACP discussions were appropriate; older adults were viewed as high priority. Our MLP’s attorney faculty, our residency director, or one of three additional physician faculty with experience in ACP then observed the resident-patient ACP discussion in the exam room with patient permission. Two of those physicians had worked in skilled nursing facilities and the third held a certificate of added qualification in geriatrics.

Evaluation

Based on the residents’ performance during the observed discussion, the faculty gave verbal feedback to the residents and discussed residents’ questions or concerns. All faculty (four physicians and one attorney) had formal training in delivering feedback through residency faculty development sessions.

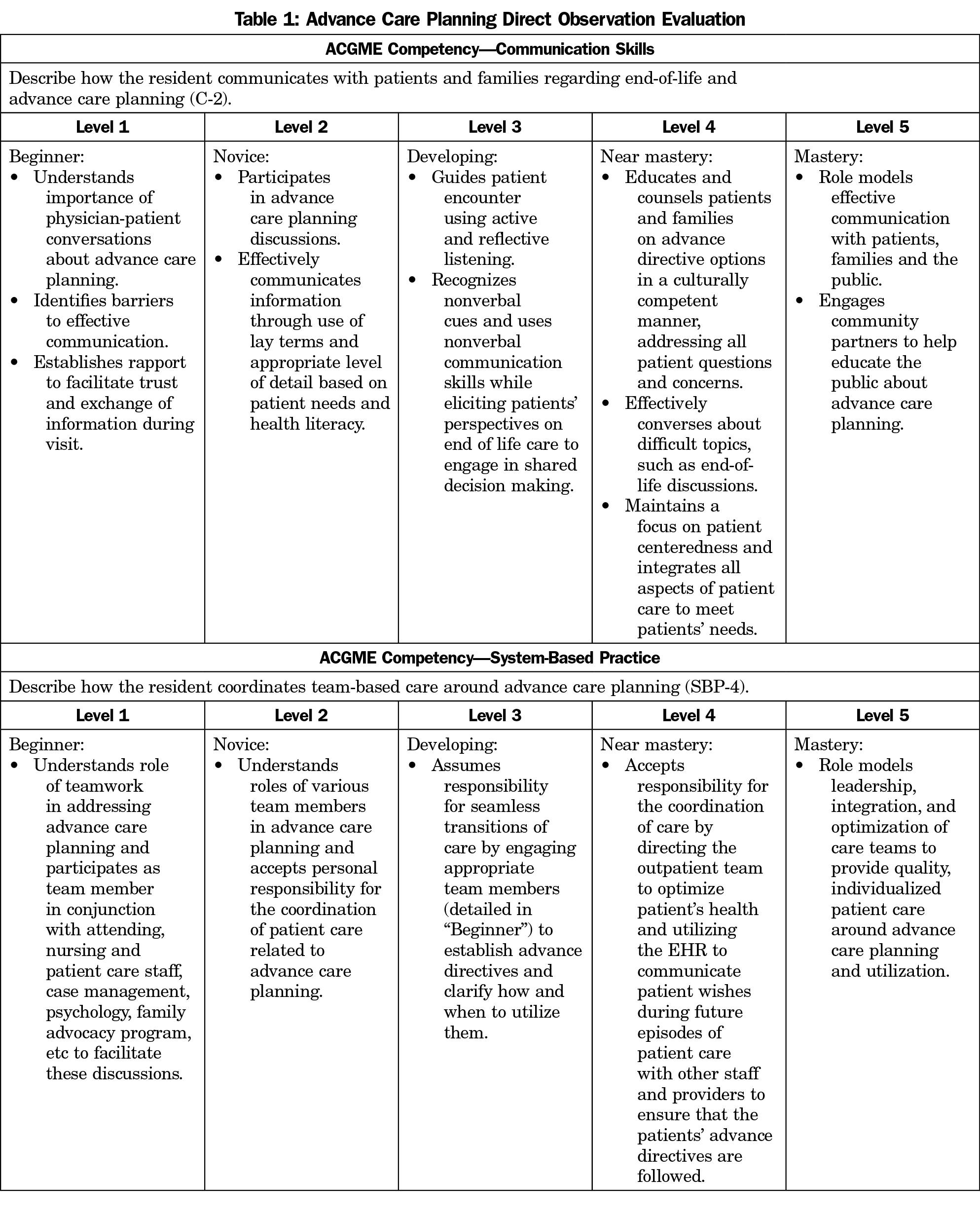

In addition, we developed an ACP-specific evaluation tool based on the Family Medicine ACGME Milestone Project.10 The evaluation tool focused on two ACGME competencies: (1) communication with patients and families, and (2) coordination of team-based care (including integration of advance directives into the electronic health record for use by hospital teams). Before observing, faculty reviewed the evaluation tool and the listed anchoring behaviors associated with ACP competency to assure agreement in assessments.

Using our evaluation tool (Table 1), we scored residents’ competence using the ACGME milestone system. Ratings included level 1 (beginner), level 2 (novice), level 3 (developing), level 4 (near-mastery), or level 5 (mastery), and were based on demonstrable skills outlined in the evaluation tool. The faculty assigned a milestone level for each of the two aforementioned competencies based on their in-exam room observation of resident performance.

We conducted 39 directly observed ACP discussions. In the first year, all eight R1s were observed three times after the introductory presentation. In the second year, seven R1s were observed twice after the presentation; due to logistical reasons, the eighth resident was only observed once.

Ten (25.6%) observations were conducted by the physicians and 29 (74.4%) were conducted by the attorney. Only the attorney provided feedback to seven (43.8%) of the 16 residents; nine (56.3%) residents received feedback from at least one physician faculty plus the attorney.

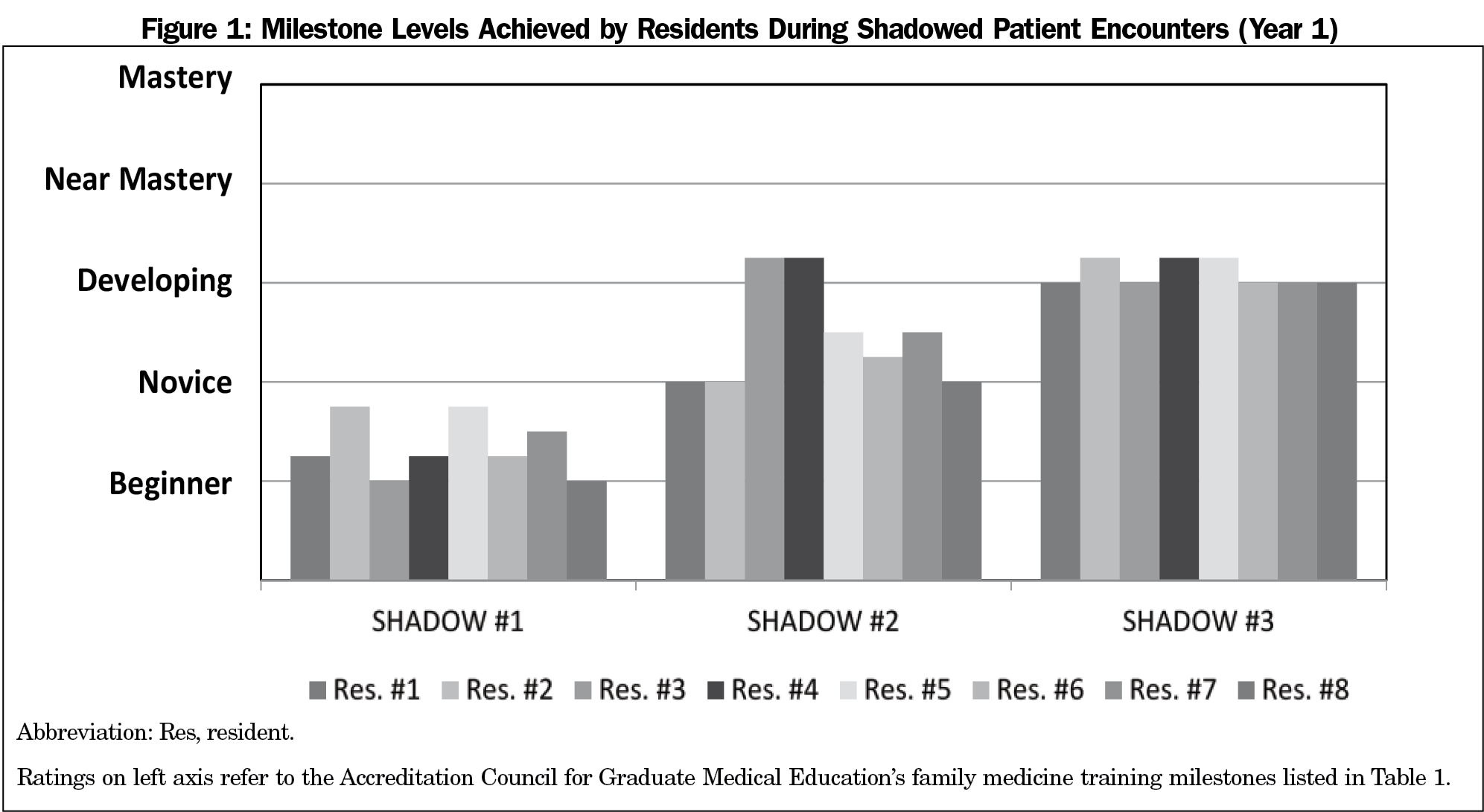

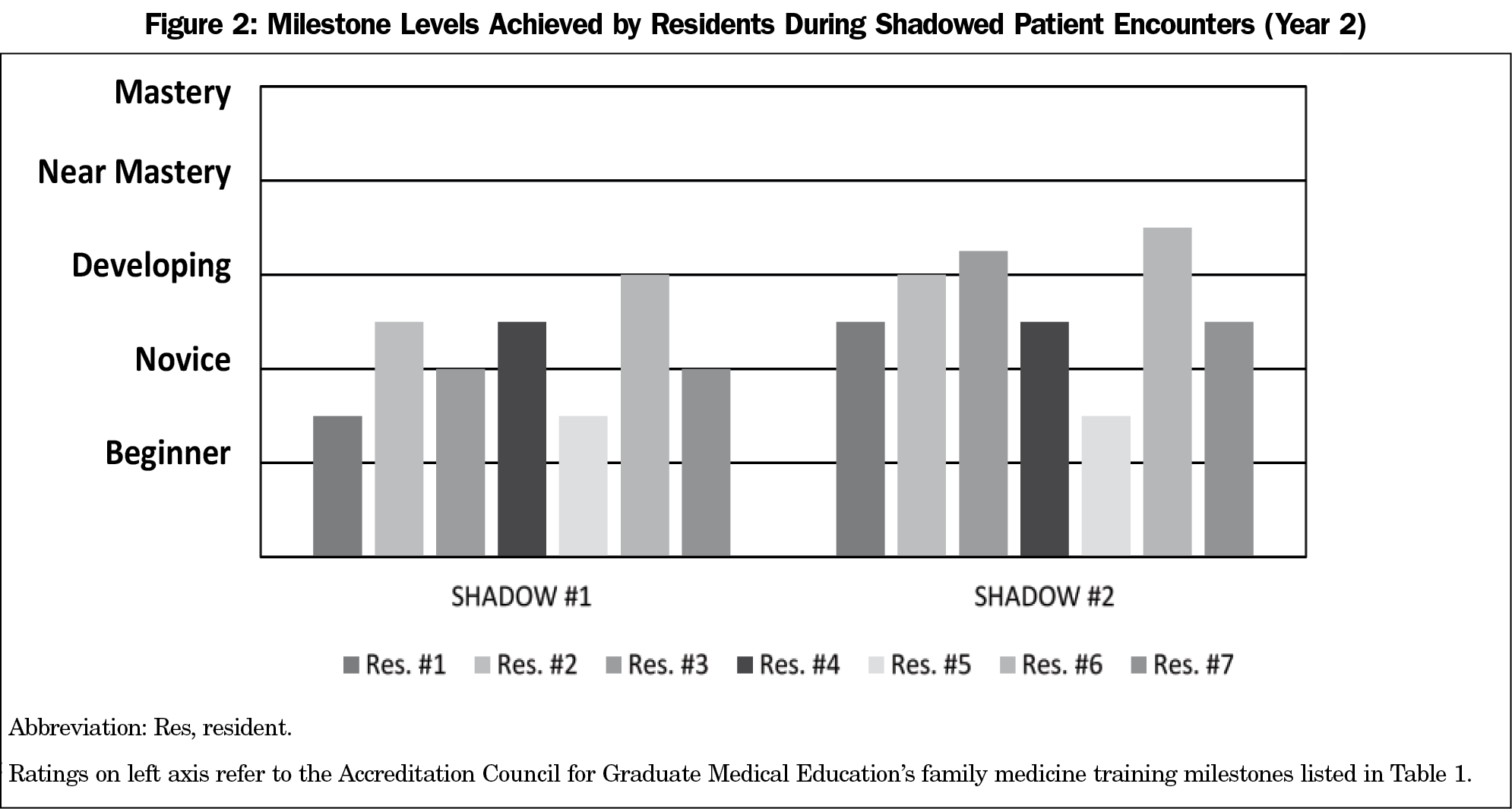

Residents’ ACP discussions with patients generally improved after each observed discussion, based on the average of the two competencies (communication with patients/families and coordination of care; Figures 1 and 2). During the first year of observations with eight R1s, most were rated either level 1 (beginner) or between level 1 and 2 (novice) in both competencies. By the third observed session, which occurred an average of 11.5 months after the initial training session, the R1s were all rated at least at level 3 (developing) for both competencies. Of the seven R1s observed twice in the subsequent year, during the second observed session (an average of 5.6 months after the initial training) three were rated as level 2 (novice) and four were rated at level 3 (developing).

After the observed discussions, residents completed a self-evaluation of an unobserved ACP discussion indicating which key topics they discussed and their confidence to do so. Residents rated their overall performance as good or excellent (scale of poor, fair, good, or excellent) and felt either fairly confident or very confident (scale of not at all, somewhat, fairly, or very confident) when discussing key ACP topics, with the exception of one resident who felt somewhat confident eliciting patients’ values to incorporate into ACP. Due to the small sample size, data were not analyzed for statistical significance.

Our results suggest that medical-legal partnerships have potential to improve residents’ competence and comfort with ACP discussions. Ratings of resident performance increased from beginner/novice levels to novice/developing levels after at least two directly observed sessions, representing an increase in competence from that of a beginning first-year resident to that expected of a second- or early third-year resident. Residents also reported increased comfort leading ACP discussions.

These results, while encouraging, must be viewed in light of several limitations including small sample size, subjective nature of ratings of resident performance, and lack of a control group of residents not exposed to the curriculum. A key next step, therefore, would be to repeat the intervention with a larger sample, using more objective outcome measures, such as the number of advance directives or ACP discussions documented in patients’ medical records, and with comparison to a control group.

Another limitation is that while our intervention improved resident performance in ACP discussions, scheduling/conducting observations was time-intensive. Each in-exam room observation and feedback session took approximately 30 minutes, which required identifying and involving faculty not serving as the day’s clinic attending physician. As a result of this time commitment, we decreased the number of direct observations from three in year 1 to two in year 2. Regardless, residents’ performance still improved, despite fewer observations.

Our experience suggests that using MLPs to teach residents how to lead ACP discussions may be more effective than previously reported approaches and resulted in sustained increases in competence over time. Additional studies are needed to confirm these preliminary findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs Ashley Wofford and Caroline Becerra, residents in their program whose initial research supported the growth of this project; Rocio Enciso, who offered administrative help; Dr Judith Gordon for her mentorship; Drs Carol Howe and Ivo Abraham; and the members of the University of Arizona Family Medicine Writing Group for their reviews and comments on the manuscript.

References

- Yadav KN, Gabler NB, Cooney E, et al. Approximately one in three us adults completes any type of advance directive for end-of-life care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(7):1244-1251. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0175

- Spoelhof GD, Elliott B. Implementing advance directives in office practice. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85(5):461-466.

- Levy D, Strand J, McMahon GT. Evaluating residents’ readiness to elicit advance care plans. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(3):364-368. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-14-00542.1

- Periyakoil VS, Neri E, Kraemer H. No easy talk: a mixed methods study of doctor reported barriers to conducting effective end-of-life conversations with diverse patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122321. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122321

- Chung HO, Oczkowski SJ, Hanvey L, Mbuagbaw L, You JJ. Educational interventions to train healthcare professionals in end-of-life communication: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0653-x

- Paul EG, Curran M, Tobin Tyler E. The medical-legal partnership approach to teaching social determinants of health and structural competency in residency programs. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):292-298. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001494

- The Education on Palliative and End-of-Life Care (EPEC) Project, Trigger Tape 1. http://library.nymc.edu/Intranet/Media/epecmod.asf. Accessed April 4, 2018.

- The Comeback. Seinfeld. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0697678/. Episode 30, Aired January, 1997. Accessed April 4, 2018.

- Anderson WG, Cimino JW, Lo B. Seriously ill hospitalized patients’ perspectives on the benefits and harms of two models of hospital CPR discussions. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(3):633-640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.08.003

- The family medicine milestone project. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(1)(suppl 1):74-86.

There are no comments for this article.