Family Medicine for America’s Health (FMAHealth) is a strategic planning organization effort that was created out of the reevaluation of the first Future of Family Medicine project from 2004. This article is a summary of the key findings of the FMAHealth Practice Core Team. At the highest level, we find that family medicine practices have compelling intrinsic and extrinsic reasons to evolve to new models of care delivery. We have demonstrated that payment transformation is imperative to successful practice transformation and that comprehensive payment models that include attention to physician work within the social determinants of health and require fewer administrative burdens will be key to achieving the quadruple aim. To bridge payment reform and practice transformation will require better and fewer measures of physician effectiveness in order to allow the physician-patient dyad to thrive in these new models. Achieving these goals will require a sustained national effort involving not only the many family medicine membership organizations, but their collaborative work with others in the health care transformation industry who may not have been our traditional partners. Educational initiatives must be robust, available to all family physicians regardless of professional organization membership, and focused on meeting physicians and physician practice managers where they are with the goal of moving them toward a state of more advanced care delivery. This article outlines the work done by the FMAHealth Practice Team that supports the above assertions.

Family medicine physicians are committed to doing everything possible to support the health of their patients, practices, and communities. In 2014, Family Medicine for America’s Health (FMAHealth) was organized as a multiyear strategic planning effort to support family physicians during an evolution of our specialty that can assure we continue to honor this commitment. Early planning defined seven core strategies. Seven core tactic teams were then created to advance these strategies, each with their own assigned set of tasks. The Practice Core Tactic Team (Practice Team) focused its work in three specific areas: (1) practice transformation, (2) practice- and payment-based continuing education needs for practicing physicians, and (3) meaningful measurement to support future primary care practice models. Work relative to area 2 also led to a collaborative effort with FMAHealth’s Payment Team, focused on potential fiscal reforms that might accelerate adoption of primary care models aligned with the triple aim of improved patient experience and improved population health supported by smarter spending.1

The process of group professional reflection, action, and advancement is endemic to the field of family medicine. In a 2004 effort to better achieve the goals of the triple aim, family medicine engaged in a similar reflective and strategic effort, then called the Future of Family Medicine (FFM).2 Importantly, FFM was able to advance a framework for new models of primary care, including the patient-centered medical home (PCMH). FFM resulted in practice and policy improvements, but the PCMH as a practice model was a touch point, not an end point.

Much has changed since work of FFM 10 years ago, and not all of it has benefitted primary care. National efforts to improve the US health care system and enhance value have also led to heavy administrative burdens for family physicians and related increases in physician dissatisfaction and burnout. It was with this in mind that FMAHealth made the intentional decision to include improvements in the work life of health care providers among their objectives. The goals of the Practice Team therefore included an expansion from the FFM focus on the triple aim to the FMAHealth focus on the quadruple aim,3 which added attention to the professional and personal health of the primary care workforce.

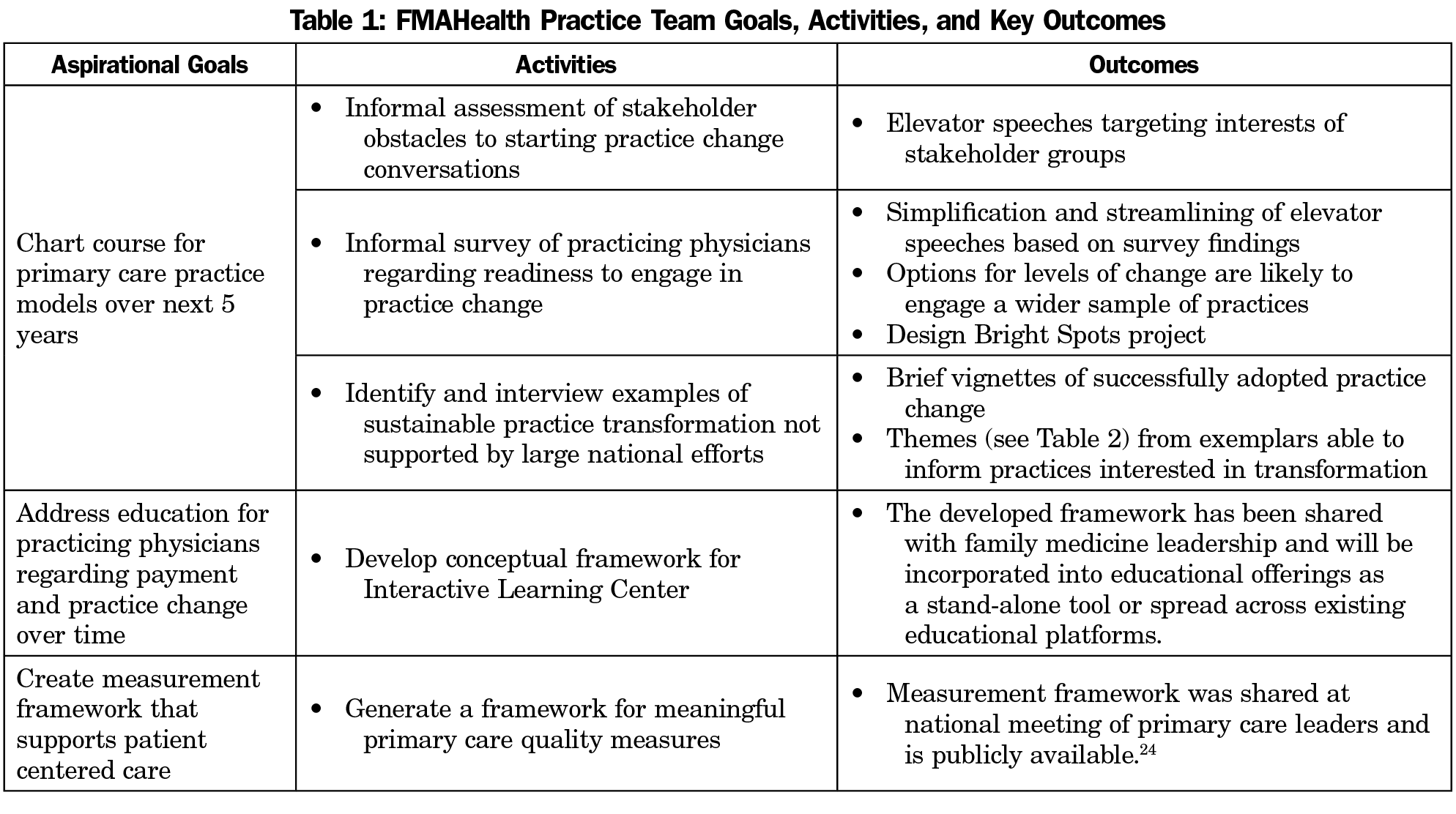

The work of the Practice Team is based on three long-term aspirational goals, developed in conversation with FMAHealth (Table 1). These goals, one naturally building upon the other, were designed to provide vision and direction for the Practice Team’s activities, with the understanding that the work started by the Practice Team would necessarily continue beyond the lifespan of FMAHealth. Therefore, an important aspect of Practice Team planning was the development of activities capable of seeding future achievement of the Team’s vision. What follows is a brief report of the five Practice Team activities completed in support of our Team’s long-term goals, the quadruple aim, and the continued revitalization of primary care practice. This work continues family medicine’s collective dedication to continuous learning, to advancing primary care, and to leading improvements in the US health care delivery system.4

The first aspirational goal of the Practice Team was to build on the success of the PCMH by charting a course that could allow for continued advancements in models of primary care practice. At a basic level, the ability to promote practice change across family medicine relies on the ability of peers to talk to peers about what practice change is and why it matters. To address that need, our team felt that the primary care community needed help to start the conversation. We conducted a brief, informal assessment of primary care stakeholder opinions at a series of professional conferences and gatherings in order to better understand how stakeholders think about practice change, the challenges they face when wanting to promote practice change, and what kinds of simple messages might help interested people get the conversation started. Informed by those conversations, the Practice Team developed a series of elevator speeches (Appendix A, https://journals.stfm.org/media/2044/marker_appendixa.pdf). These elevator speeches serve as brief key messages tailored to the interests of each group, and are intended to spark conversation.

Support and fostering of widespread practice transformation is of clear benefit to population health and the improvement of the US health care system. There remains, however, varied capacity, skill, and motivation among primary care practices to conduct the self-assessment and planning required to implement necessary changes. In order to facilitate movement toward practice transformation, our team wanted to influence creation of tools that could meet practices where they are. This required developing an easy way to identify and classify where practices might be along a continuum of interest in change. Our team adapted findings from the “readiness to change” literature to develop and field a quick, low-impact readiness to change assessment among physicians.5 While we understood that most practices function as teams of interdisciplinary leaders, time and resource constraints required that we field test our survey among physicians only.

The stages of change model (Precontemplation, Contemplation, Readiness, Action and Maintenance) provides an easy-to-use framework to assess readiness for transformation.5 It was not initially clear whether a readiness for transformation survey would prove meaningful. Fielding our survey during group interviews with several dozen physicians attending a variety of professional meetings and continuing education events, we found that physicians easily self-identified into one of the stages of change as it relates to their motivation to change practice models of care delivery. Further, conversations during the group interviews revealed that in addition to the intensive national efforts currently underway,6-8 a large number of physicians are intrinsically motivated to adopt practice change but have modest means. We found that “meeting practices where they are” also meant creating a resource list of a small number of easily identified, low-impact care delivery changes.3

Another Practice Team activity that supported practice transformation was a direct response to a common request made by physicians responding to our readiness for transformation survey. These physicians shared an interest in learning about current sustainable examples of transformation. They felt learning from practice changes previously adopted by their peers, and not as part of national transformation programs, would allow them to assess the feasibility and financial burden associated with a particular practice change more effectively. Using known sustainable examples of practice transformation and a snowball sampling approach, our team interviewed a series of practices that had completed some form of transformation, found it sustainable, and found that it resulted in gains related to the quadruple aim. Themes that emerged through the Bright Spots9 work (Table 2) provide important insights for physician education organizations to structure learning opportunities.

This goal of the Practice Team targeted updates to practice education offerings that would allow current practicing physicians to build capacity to respond to future payment and practice model changes. We are not the only group interested in working in this space. Many national efforts are currently underway to determine the most efficient practice models for administering patient-centered care,6-8 and they have already generated several useful educational guides to support ongoing transformation.10 For example, Colorado’s Practice Innovation Program Colorado11 includes tools that help practices assess their capacity for change, to assess the readiness of individual team members for change, and to adopt a basic building block approach to practice change.12 Similar tools are available from the American Medical Association’s STEPS Forward13 project and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Primary Care Team Guide project.14

The Practice Team had no interest in duplicating or competing with the strong work already being conducted by large-scale transformational efforts. Drawing on the data our team collected during the readiness to transform survey and the Bright Spots project, we realized and sought to fill an apparent unmet need: to facilitate practices easily accessing the right education delivered at the right time and in the right way.

The amount of educational information already available was large, widely dispersed, and not easily navigated by those without direct engagement in federal- and foundation-funded transformation initiatives. Successful promotion of practice transformation involves meeting practices where they are. Previous research supports that doing so can foster greater intrinsic motivation for change.15 It therefore follows that educational offerings need to be tangible, useable, individualized, meaningful, and self-led.

To that end, our team developed a conceptual model for an Interactive Learning Center. Once created, this Learning Center could provide primary care physicians and practices with several benefits. Key to the Learning Center design is a regularly updated and indexed list of educational resources, cross tabulated to individual practice needs. Ideally, the educational resources would be linked to peer-to-peer learning opportunities, quick links to vetted third-party resources, and the possibility of continuing medical education credits or maintenance of board certification points. An interactive learning center could reduce the administrative obstacles to practice change and support individual clinician and team member access to education delivered in a way that facilitates efficient practice transformation. Whether an interactive learning center exists as a stand-alone entity or is integrated into the electronic resources of existing educational platforms will need additional study.

The third Practice Team aspirational goal was to create a vision for quality measures able to support patient-centered models of care—the purpose of practice transformation efforts. Over the past decade we have witnessed an explosion of quality measures intended to support the triple aim. Thousands of primary care measures are currently in use.16 Many of those measures are disease oriented, misaligned with family medicine’s focus on whole-person relational care, and have yielded more administrative burden than improved health.17,18 New measures are required that are suitable to the task of assessing primary care, fostering improvement, supporting continuous learning, and advancing practice transformation. Several primary care organizations are engaged in efforts to generate a more parsimonious list of quality measures. Still, the question remains, are we measuring what matters? Is it possible that we are more focused on measuring that which we know how to count rather than that which we have come to value?19 Efforts that remain focused on the reduction of currently-used primary care measures will help to address measure-related burden and waste. However, without significant redesign of measurement frameworks, limiting possible quality measures to those already created will continue to fail as adequate support for primary care transformation and growth.

To address this concern, the Practice Team focused on generating a meaningful framework for primary care measures that matter. The American Board of Family Medicine Foundation previously funded a national survey among primary care clinicians regarding those characteristics most important to the provision of high-quality primary care.20 Through FMAHealth, our team expanded on that data set by fielding similar surveys among a diverse national cohort of patient and employer stakeholders. Results from both survey efforts were used to create a first draft of a meaningful framework for primary care measures that was then vetted, discussed, and revised at the Starfield Summit III: Meaningful Measures for Primary Care.21

Collaboration Between the FMAHealth Practice and Payment Teams

The advancements generated by the 2004 Future of Family Medicine project were impressive, but limited in impact by the relative stagnation of payment reform. Their experience made it clear that practice transformation cannot happen without the financial structures and resources required to support high-quality primary care. While conducting surveys and interviews during the Readiness for Transformation and Bright Spots projects, the Practice Team found no situations in which financial incentives alone motivated physician interest in transformation. However, financial barriers were often identified as an obstacle to change adoption or as the reason why such changes would not be considered. This was true among physicians working in small practices as well as those in large private practices, health systems, and teaching facilities.

The Practice Team collaborated with FMAHealth’s Payment Team to identify and define the services that should be included in comprehensive care and to show the cost of those services for any geographically-defined population. This work is described in greater detail by The Payment Team (see “Development, Value, and Implications of a Comprehensive Primary Care Payment Calculator for Family Medicine” by Aaron George, DO, et al, in this issue22). Such tools make it possible to determine the proper payment for primary care services and to allow for prospective, periodic payments requiring few administrative strings. Asking family physicians to transform their practices while managing the revenues from value-based care comes with some financial risk—risk that can be somewhat mitigated by the proper planning these tools allow. Practice and payment reform will always be interdependent. Therefore, efforts to encourage practice transformation will always benefit from planning that fully integrates strategic attention to practice and payment.

While the FMAHealth project comes to a close, the sponsoring organizations of FMAHealth remain committed to the work initiated by its core tactic teams. Elevator speeches created as part of the team’s first aspirational goal have been distributed among the sponsor organizations for use among their membership. Data collected as part of the Bright Spots project are being converted into short informational videos that will serve educational purposes for physicians working on practice transformation. As noted above, the conceptual framework for sharing these best practices through an Interactive Learning Center is receiving additional evaluation of the best methods to deliver this dynamic content. Work on meaningful measures for primary care is continuing through a collaboration of the Larry A. Green Center for the Advancement of Primary Health Care for the Public Good, the American Board of Family Medicine, the Center for Professionalism and Value in Health Care, and the Center for Community Health Integration.

As we look back to our original charge in the 2016 special issue of Family Medicine, the FMAHealth Practice Team continues to believe that meaningful practice transformation able to achieve the quadruple aim is not only possible, but has already happened in many areas of the country and in many practices. With appropriate support and reform, family medicine and primary care are poised for rapid growth facilitated by simple practice changes applied broadly across the United States. Practice transformation—always striving to do better for our patients, our practices, and our communities—can lead to the advancement of the quadruple aim, improving both population health and the professionalism of family medicine for generations. It has been our pleasure to research the process changes needed for success and we remain optimistic about the future of our specialty.

Acknowledgments

All authors are volunteer members of the Family Medicine for America’s Health Practice Core Team.

References

- Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759-769. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759

- Martin JC, Avant RF, Bowman MA, et al; Future of Family Medicine Project Leadership Committee. The Future of Family Medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 1):S3-S32. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.130

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-576. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1713

- Saultz JW, Jones SM, McDaniel SH, et al. A New Foundation for the Delivery and Financing of American Health Care. Fam Med. 2015;47(8):612-619.

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51(3):390-395. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.51.3.390

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. EvidenceNOW: Advancing Heart Health in Primary Care. http://www.ahrq.gov/evidencenow/summary.html. Published September, 2017. Accessed September 2017.

- 7. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Comprehensive Primary Care Plus. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/comprehensive-primary-care-plus/. Accessed June 22, 2018.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Transforming-Clinical-Practices/. Accessed June 22, 2018.

- Heath C, Heath D. Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard. New York: Broadway Books; 2010.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. The Medical Home. https://www.aafp.org/practice-management/transformation/pcmh.html. Accessed June 26, 2018.

- 11. Practice Innovation Program Colorado. About Us. http://www.practiceinnovationco.org/about/. Accessed June 26, 2018.

- Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard-Grace R, Grumbach K. The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):166-171. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.161

- American Medical Association. AMA Stepsforward. https://www.stepsforward.org/. Accessed June 26, 2018.

- Improving Primary Care. The Primary Care Team Guide. http://www.improvingprimarycare.org/. Accessed June 16, 2018.

- Geonnotti K, Taylor EF, Peikes D, et al. Engaging Primary Care Practices in Quality Improvement: Strategies for Practice Facilitators. AHRQ Publication No. 15-0015-EF 2015; https://www.pcmh.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/QI-strategies-practices.pdf. Accessed June 26 2018.

- Conway PH; Core Quality Measures Collaborative Workgroup. The Core Quality Measures Collaborative: A Rationale and Framework for Public-Private Quality Measure Alignment. Health Affairs Blog; June 23, 2015. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20150623.048730/full/. Accessed January 9, 2019.

- Etz RS. Historical Context for PC Measures Work. Starfield Summit III Conference Brief; 2017; Washington, DC.

- Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of Physician Time in Ambulatory Practice: A Time and Motion Study in 4 Specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(11):753-760. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-0961

- LeFevre M. It Matters What Is Measured. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(1):8-9. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160362

- Etz RS, Gonzalez MM, Brooks EM, Stange KC. Less AND More Are Needed to Assess Primary Care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(1):13-15. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160209

- Starfield Summit. Starfield III: Meaningful Measures for Primary Care. http://www.starfieldsummit.com/starfield3/ Accessed June 26, 2018.

- George A, Sachdev N, Hoff J, et al. Development, value, and implications of a comprehensive primary care payment calculator for family medicine: report from Family Medicine for America’s Health Payment tactic team. Fam Med. 22019;51(2):185-192.

There are no comments for this article.