Background and Objectives: In order to address racial health inequity, it is imperative to create diverse physician workforce and leadership. We describe and report on the outcomes of a comprehensive diversity initiative at our residency with the goal of increasing the racial diversity of residents and faculty.

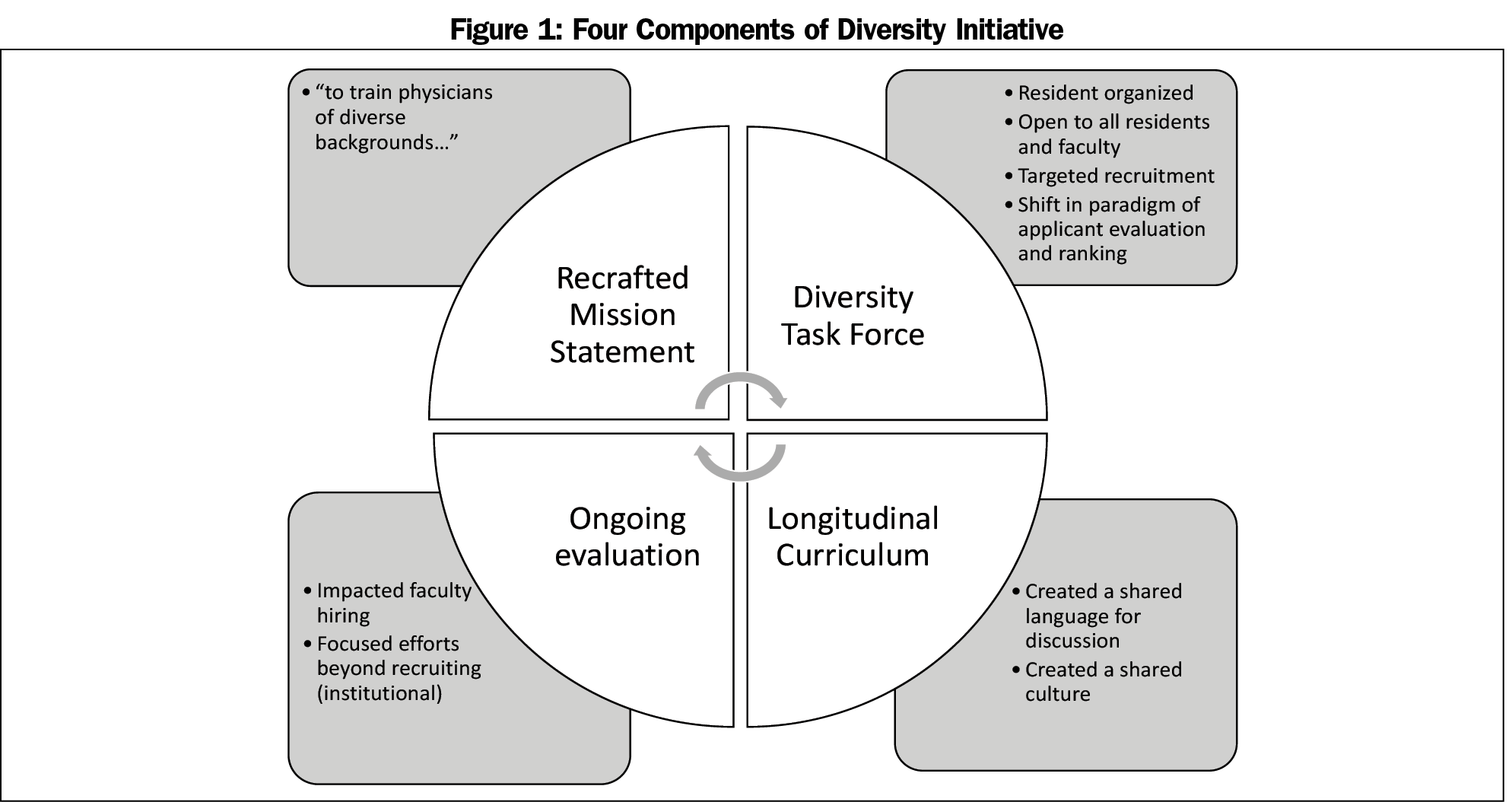

Methods: At a community-based family medicine residency program, we instituted a multifaceted diversity initiative. The four components were mission statement revision, a diversity task force, an antiracism curriculum, and an ongoing system to evaluate progress.

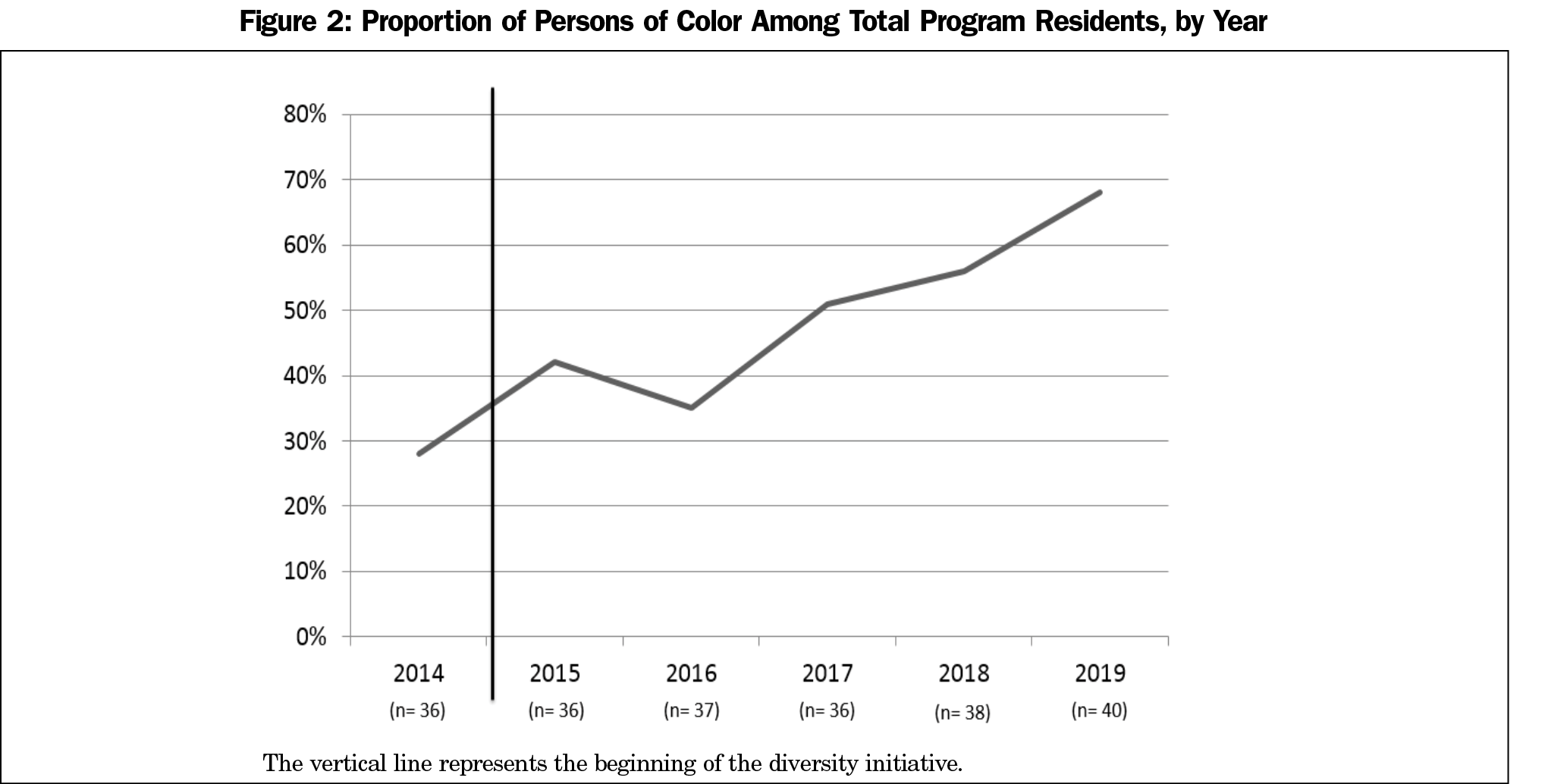

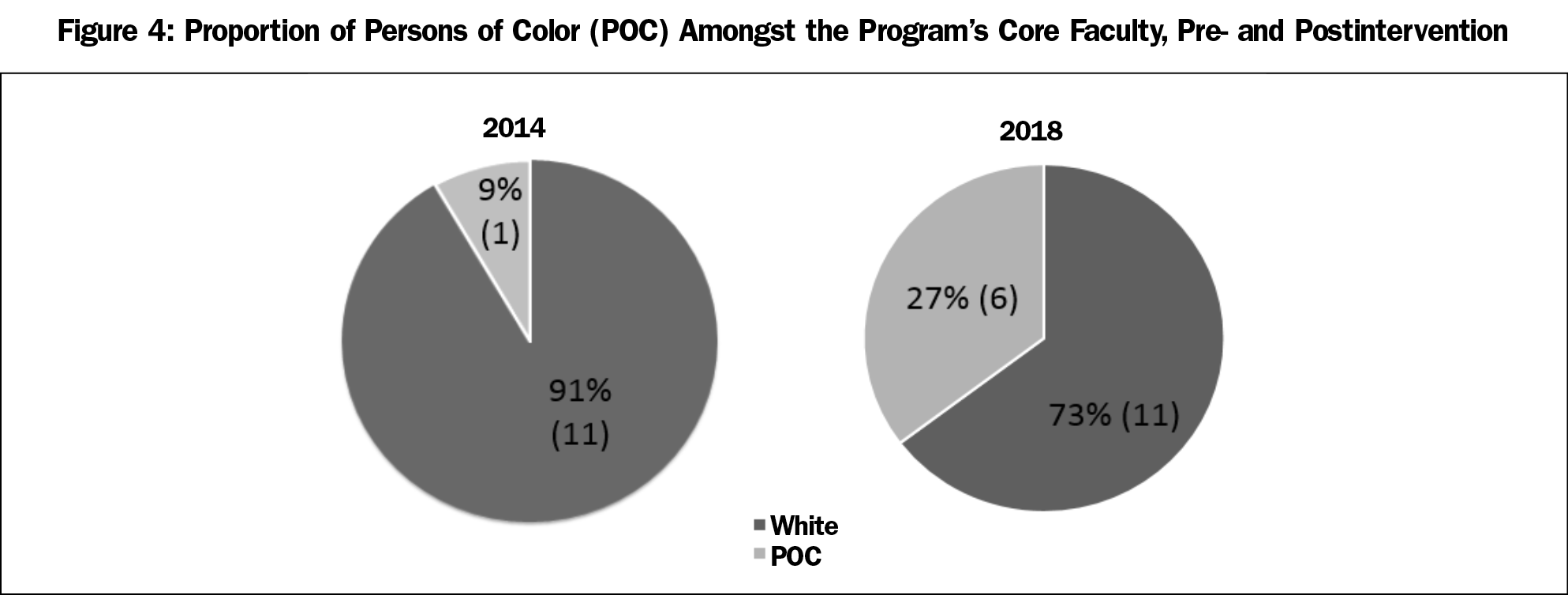

Results: From 2014 to 2017, the proportion of persons of color among the residents increased from 28% (10/36) to 68% (27/40). Faculty diversity increased from 9% to 27% over the same period.

Conclusions: This multimethod diversity initiative dramatically increased the proportion of underrepresented and other minorities in the residency program. The intervention succeeded due to the commitment of leadership and resources to addressing racism and making diversity a top priority on an institutional level.

Racial health disparities persist in American health and health care. These disparities manifest in higher mortality, worse health outcomes, greater comorbidity, and mistrust of the health care system.1,2 Increasing the racial diversity of the physician workforce can help eliminate racial health inequity. A 2006 review found that physician-patient race concordance increases patient satisfaction, patient comprehension, and continuity of care.3-6 Increasing racial diversity is also an evidence-based intervention to combat implicit bias, a powerful driver of racial health inequity.7 Furthermore, racially diverse teams outperform less diverse ones.8

An important step is increasing the racial diversity in residency training programs. While strategies have been identified to increase racial diversity in medical schools, there is limited evidence in the setting of graduate medical education.9-12 We describe and report on the outcomes of a comprehensive diversity initiative at our residency with the goal of increasing the racial diversity of residents and faculty.

Swedish Family Medicine Cherry Hill is a community-based family medicine residency affiliated with the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle, Washington. The mission of the program is to train full-spectrum family medicine physicians to care for the underserved. In 2014 we began a multifaceted diversity initiative with the goal of increasing racial diversity in our residency. The four components of the initiative were mission statement revision, a diversity task force, an antiracism curriculum, and an ongoing system to evaluate our progress (Figure 1). This initiative was funded from the residency budget with the exception of subinternship stipends, which were funded by the Swedish Foundation Fund.

Mission Statement

The mission statement is an important reflection of a program’s goals and values. In 2014, during a program-wide diversity workshop, we revised our mission statement to include a commitment to “training physicians from diverse backgrounds.”

Diversity Task Force

We formed a diversity task force of residents and faculty to improve recruitment. We sent racially diverse representatives to the American Academy of Family Physicians National Conference of Family Medicine Residents and Students. While there, we invited interested persons of color (POC) to have breakfast with us and we discussed our residency’s goal of racial social justice. We attended minority medical student organization conferences and reached out to historically black medical schools. We increased the recruitment of POC students into our subinternships and offered stipends.

The diversity task force made fundamental changes to our process of evaluating applicants. We changed our interview scoring rubrics to place greater value on the “lived experience” of being a POC, recognizing that many POC students face additional cultural, linguistic, familial, or financial barriers to completing medical school. Additionally, we developed standardized interview questions to assess applicants’ perspectives regarding the underrepresentation of racial minorities in the physician workforce and racial health inequity.

We changed our rank system from a process-oriented approach to goal-oriented approach.13 We established an academic threshold that we felt predicted success. We added a prerank night for additional discussion time to ensure POC applicants were well represented on rank night.

Curriculum

We developed curriculum for residents and faculty with informational content as well as individual self work. We developed a mandatory “Race and Medicine” workshop for interns that explores the historical context of racialization, privilege, and implicit bias. We designed an optional “race reading group,” hosting facilitated discussions using preassigned texts that explore topics such as housing, education, mass incarceration, model minority, immigration, appropriation, intersectionality, and facilitating difficult conversations. We have continued to hold a mandatory annual race workshop tailored to address race in our residency community.

In addition to resident recruitment, these changes informed faculty hiring practices as well. The mission and program culture emphasized diversity; the diversity task force also informed faculty hiring process, and faculty participated actively in the curricular changes.

Evaluation

Each year we tracked POC, URM, and mURMs in our applicant pool, interview pool, matchable range on our rank lists, and in each intern class. Our minimum goal was to match resident racial demographics to our patient populations. We regularly solicited feedback on our recruitment process and antiracism curriculum. Finally, we sent follow-up surveys to highly ranked POCs who matched elsewhere.

Data Analysis

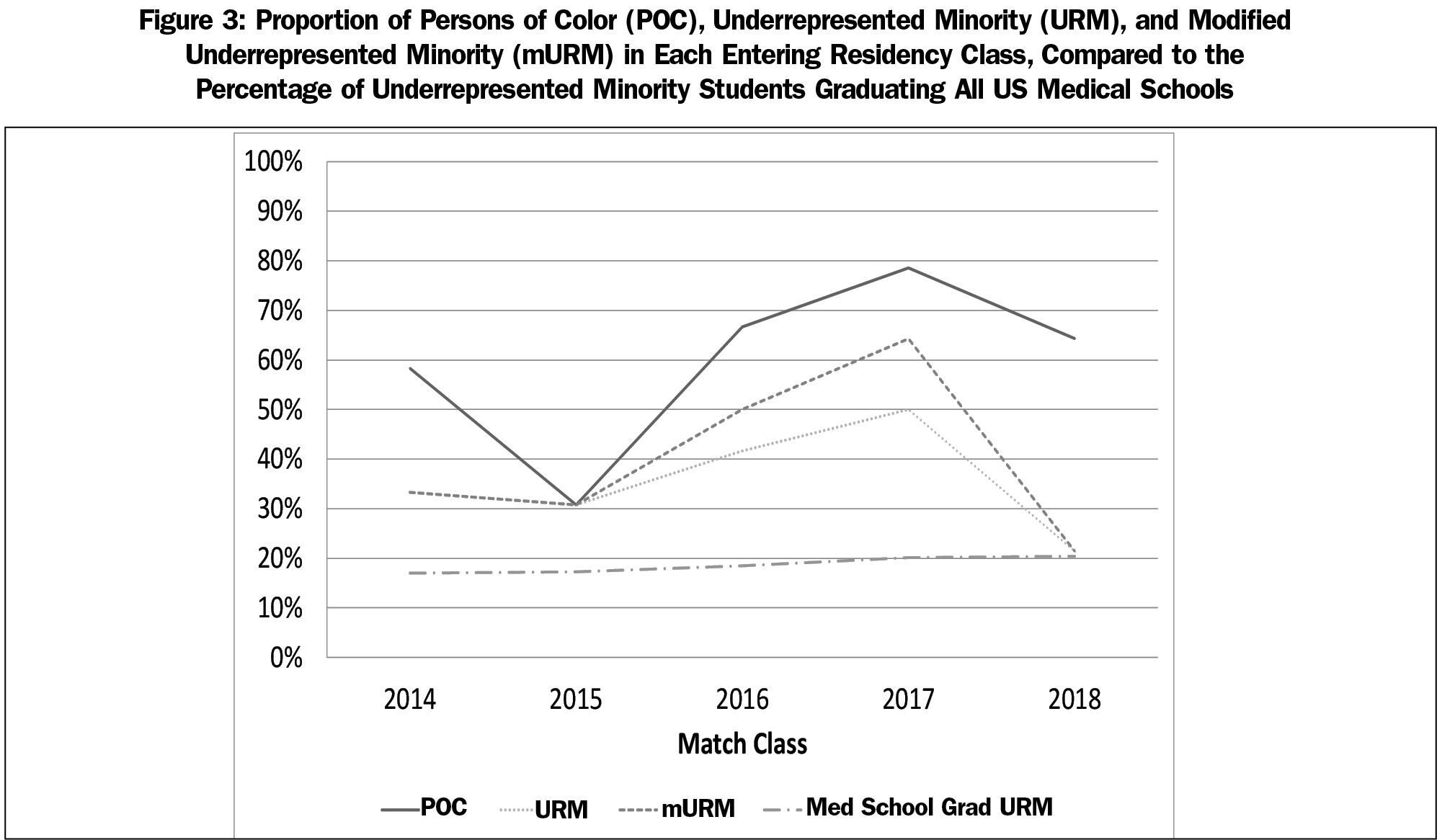

We defined POC to include any person who does not identify as non-Hispanic white. We defined URM by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) definition including blacks, Latinx, and Native Americans. We developed a “modified URM” category (mURM), which includes all POCs except for people of Chinese, Korean, and Indian descent.

We analyzed proportions of POC, URM and mURM amongst residents in our program each year. We examined both the total as well as each year’s matriculating match class. As the data reflect the entire cohort, and the numbers are small, we did not perform statistical testing. The Swedish Institutional Review Board reviewed this work and found it to be exempt.

In the 3 years prior to our racial diversity initiative, 10 of 36 residents (28%) self-identified as POC. After implementation of the program changes, the proportion of POC increased to 68% (27/40; Figure 2).

Figure 3 demonstrates the proportion of POC, URM and mURM in each residency matriculation class. The percentage of POC residents in each match class has increased since the introduction of the initiative. The overall percentage of URMs and mURMs has also increased.

Prior to the intervention in 2014, only one of 12 (8%) faculty identified as POC; by 2018, 27% of faculty (6/17), self-identified as POC (Figure 4).

We report the results of a diversity initiative in a community-based, university-affiliated family medicine residency program. We increased the percentage of residents who identify as POC from 28% to 68% in the span of 4 years. As a result of the diversity initiative, there has been an overall increase in URMs.

The most important lesson we learned is the need to place addressing racism and diversity as a top priority and committing resources to support it. Our success was directly related to winning the support of leadership and the commitment of resources such as didactics time, financial support for consultants and speakers, blocking clinical duties, and faculty full-time equivalents.

Although graduate medical education is the completion of the physician diversity pipeline, we found that this work greatly improved all residents’ and faculty’s understanding of the social determinants of health and how to advocate for patients and communities. Our residency is a far more supportive space for racial minorities and this has led to antiracism work within our sponsoring institution.

We recognize this study describes a small sample at a single program, which limits generalizability. The complexity and long timeline of residency recruitment make it difficult to know whether outcome changes are real and will persist, but our 4 years of data demonstrate a dramatic effect.

Looking forward, the most imperative issue is sustainability. We must consider effective ways for us to engage in mURM pipeline work and advocate for racial equity in public education. We need additional support structures for residents and faculty of color. Finally, it is imperative that this work is passionately shared amongst the community as opposed to a few champions.

Acknowledgments

This report was presented at the STFM Annual Spring Conference, Washington DC, May 5-9, 2018.

References

- Heckler MM. Report of the Secretary’s task force on black and minority health. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1985.

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2003.

- Saha S, Shipman SA. The rationale for diversity in health professions: a review of the evidence. Washington, DC: Health Resources and Services Administration; 2006.

- Saha S. Taking diversity seriously: the merits of increasing minority representation in medicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):291-292. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12736

- Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(5):90-102. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.90

- Pierre JM, Mahr F, Carter A. and Madaan V. Underrepresented in medicine recruitment: rationale, challenges, and strategies for increasing diversity in psychiatry residency programs. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(2):.226-232.

- Burgess D, van Ryn M, Dovidio J, Saha S. Reducing racial bias among health care providers: lessons from social-cognitive psychology. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):882-887. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0160-1

- Hunt V, Prince S, Dixon-Fyle S, Yee L. Delivering through diversity. New York: McKinsey & Company; 2018.

- Boatright D, Tunson J, Caruso E, et al. The impact of the 2008 Council of Emergency Residency Directors (CORD) panel on emergency medicine resident diversity. J Emerg Med. 2016;51(5):576-583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.06.003

- Vick AD, Baugh A, Lambert J, et al. Levers of change: a review of contemporary interventions to enhance diversity in medical schools in the USA. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:53-61. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S147950

- Ballejos MP, Rhyne RL, Parkes J. Increasing the relative weight of noncognitive admission criteria improves underrepresented minority admission rates to medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27(2):155-162. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2015.1011649

- Association of American Medical Colleges. AAMC Analysis in Brief. 2013;13(6).

- Tatum BD. Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?: And Other Conversations About Race. New York: Basic Books; 2003.

There are no comments for this article.