Background and Objectives: Postgraduate education in cultural competence and community health is a key strategy for eliminating health disparities in underserved populations. Evidence suggests that an experiential, rather than knowledge-based approach equips physicians with practical and effective communication tools that generalize to a greater diversity of patients and cultures. However, there is limited data about the efficacy of a longitudinal, experiential residency curriculum. This study details the results of a longitudinal underserved community curriculum for family medicine residents training in a federally qualified health center.

Methods: All residents in the first 5 years of a new residency participated in a longitudinal curriculum of workshops and seminars focused on social determinants of health and cultural competency for underserved patients. Pre- and postcurriculum surveys assessed knowledge gain. Self-reported Likert scale ratings assessed attitudes and confidence related to underserved care.

Results: Pre/post learning evaluations after each seminar documented average knowledge increase of 31.0% and 28.8%, respectively. At the end of the 3-year curriculum, 81.8% of residents reported confidence in their ability to incorporate culturally relevant information into a treatment plan and 57.1% of residents reported feeling very aware of obstacles faced by underserved populations seeking health care and of the relationship between sociocultural background, health, and medicine.

Conclusions: A longitudinal, experiential curriculum in underserved community health and cultural competence can improve resident knowledge and attitudes with respect to health disparities and delivering health care to diverse patient populations.

Cultural competence is a key strategy for addressing growing health disparities.1-6 Postgraduate (PG) medical cultural competence education has traditionally been a knowledge-based approach to diverse cultural beliefs, values, and behaviors.2 However, didactic approaches may fail to acknowledge diversity within groups and potentially reinforce stereotyping.1,4

A more effective approach may be to engage residents directly with patients to explore social, cultural, and economic factors that influence health care decisions and treatment adherence.2,4,6 This experiential skills-based approach can equip physicians with tools that are effective across diverse populations.1,3

Although the relationship between provider cultural competence and clinical outcomes needs further study, research suggests that lack of attention to cultural issues can negatively impact patient satisfaction and treatment adherence.5 Educators recommend multifaceted cultural competence education taught throughout the duration of medical education.7,8 However, there is limited data on longitudinal residency curriculum to increase the cultural competence of physicians in an urban underserved area.

This study describes the design, implementation, and evaluation of a longitudinal underserved community curriculum (LUCC) implemented during the first 5 years of an urban underserved family medicine residency.

Curriculum

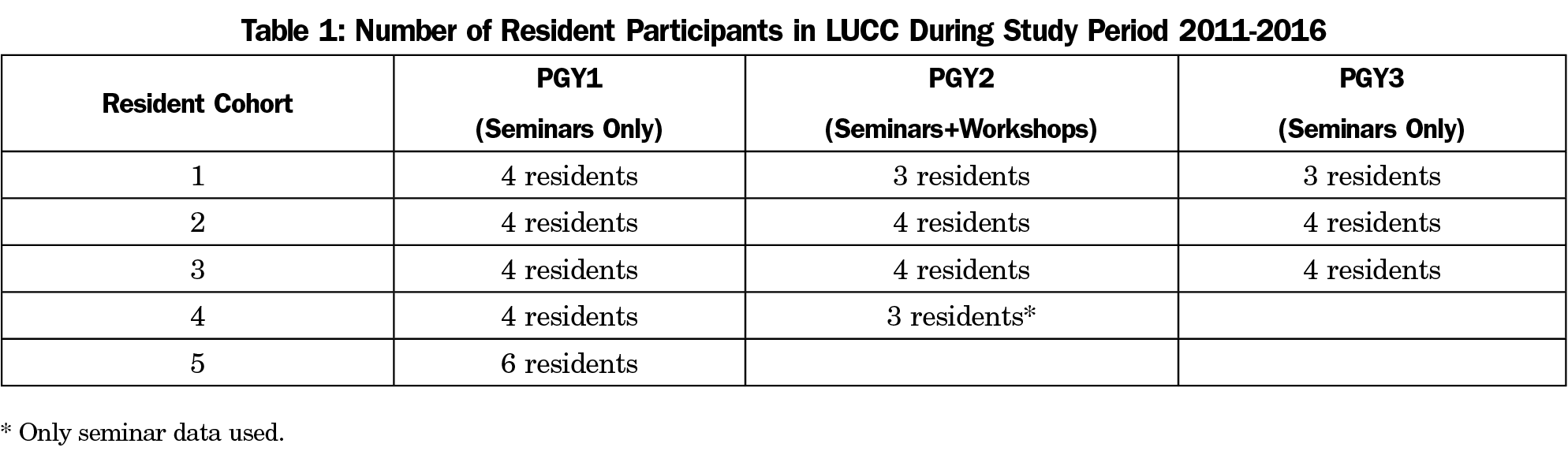

From July 2011-June 2016, all residents (N=22) in a new Saint Louis University Family Medicine Residency in St Louis, Missouri participated in aspects of the LUCC (Table 1). Three cohorts of residents (N=11; 57.1% female) completed the entire 3-year curriculum including 12 monthly day-long community health workshops during PGY2 focused on health disparities and cultural competencies in urban underserved care. Cohorts four and five completed 2 and 1 year of curriculum, respectively, during the study period.

Monthly day-long experiential workshops for PGY-2 residents were mentored by faculty practicing in underserved care and designed to maximize resident engagement. Workshops included conversations with patients, visits to community organizations, introduction to resources, hands-on clinical workshops, fieldwork, short didactic sessions, and awareness raising exercises. For example, in the addiction and homelessness workshop, residents accompanied outreach professionals into the field to immunize and discuss health related topics with patients.

Monthly community-focused 1-hour seminars for all residents were led by guest speakers from ethnic communities or community agencies and addressed cross-cultural health, health disparities, behavioral health, violence, and health policy.

All residents practiced in a diverse urban federally qualified health center (FQHC) with patients served in a language other than English (15%) and patients below the poverty level (55%).

Evaluation

Written pre- and posttests at each workshop or seminar evaluated knowledge gain and included written feedback. After each block of 12 PGY-2 workshops, a staff researcher conducted a focus group that was transcribed for feedback and quality improvement. An electronic annual resident survey measured resident confidence and attitudes at the start of PGY1 and late in PGY3. This survey was informed by a systematic review of self-administered measures of cultural competence of health professionals and includes items from the Modified Cultural Competency Self-Assessment Questionnaire,9 the Transcultural Self-Efficacy Tool,10,11 the Cultural Assessment Survey,12 and the Socio-cultural Attitudes in Medicine Inventory.13 All surveys were anonymous, thus pre- and posttests were not matched.

Data Analysis

Pre/post intervention comparative design evaluated knowledge, confidence, and attitudes. The PGY-1 baseline annual resident survey binary confidence and attitude scores were compared to PGY-3 scores using Fisher exact tests. Change in knowledge scores for pre- and posttests for workshops and seminars (Tables 2 and 3) were assessed using independent samples t-tests. Pre- and posttests were not matched, hence, paired sample analysis could not be conducted. All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Qualitative responses were independently analyzed for themes by the first two authors.

The Saint Louis University Institutional Review Board determined evaluation of the curriculum and resident learning to be an exempt study.

Learner Outcomes

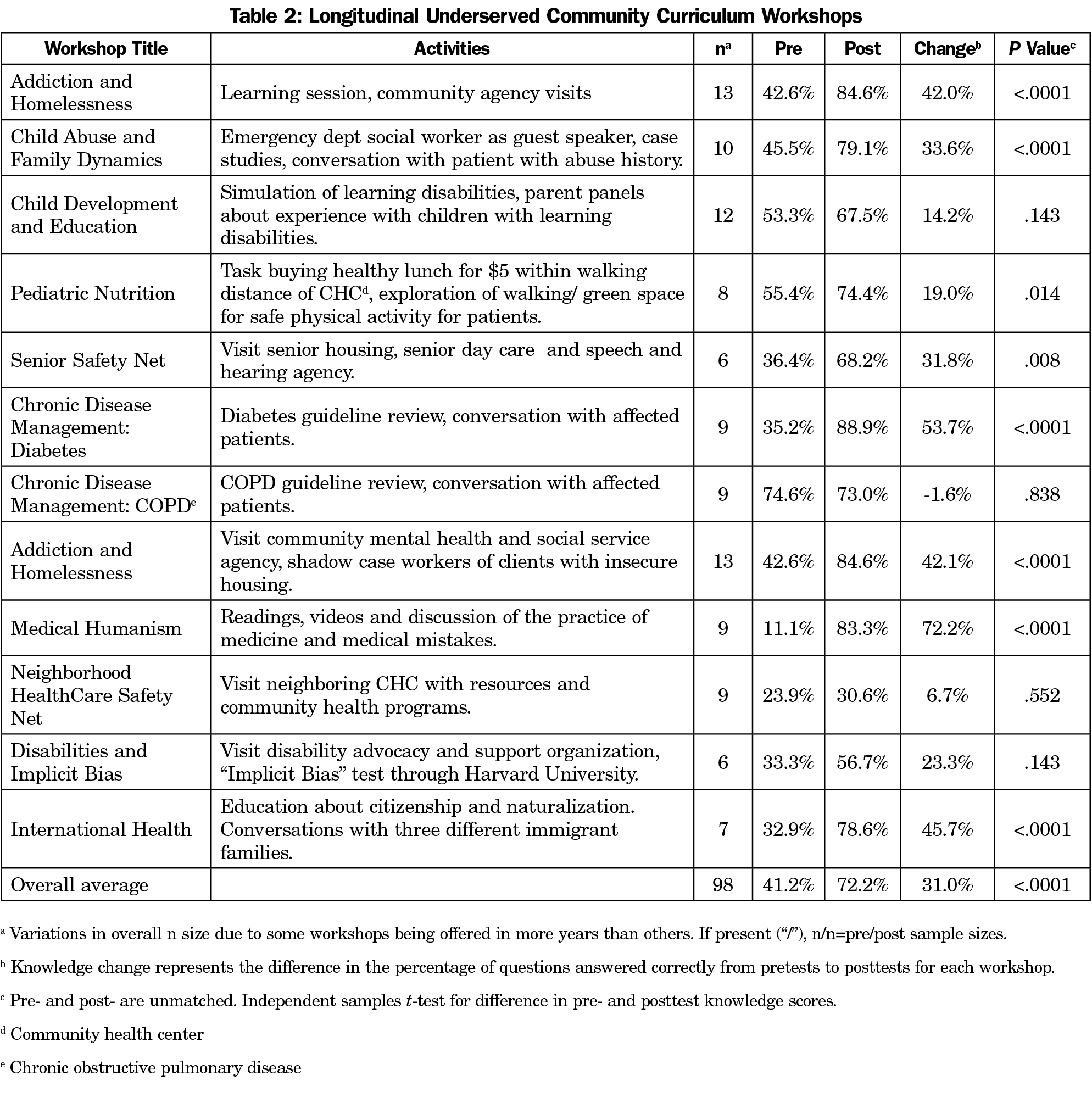

Resident knowledge after the PGY-2 day-long workshops (Table 2) increased 31.0% (P<0.0001). Average resident knowledge after the seminars with pre- and posttests (Table 3) increased 28.8% (P<0.0001).

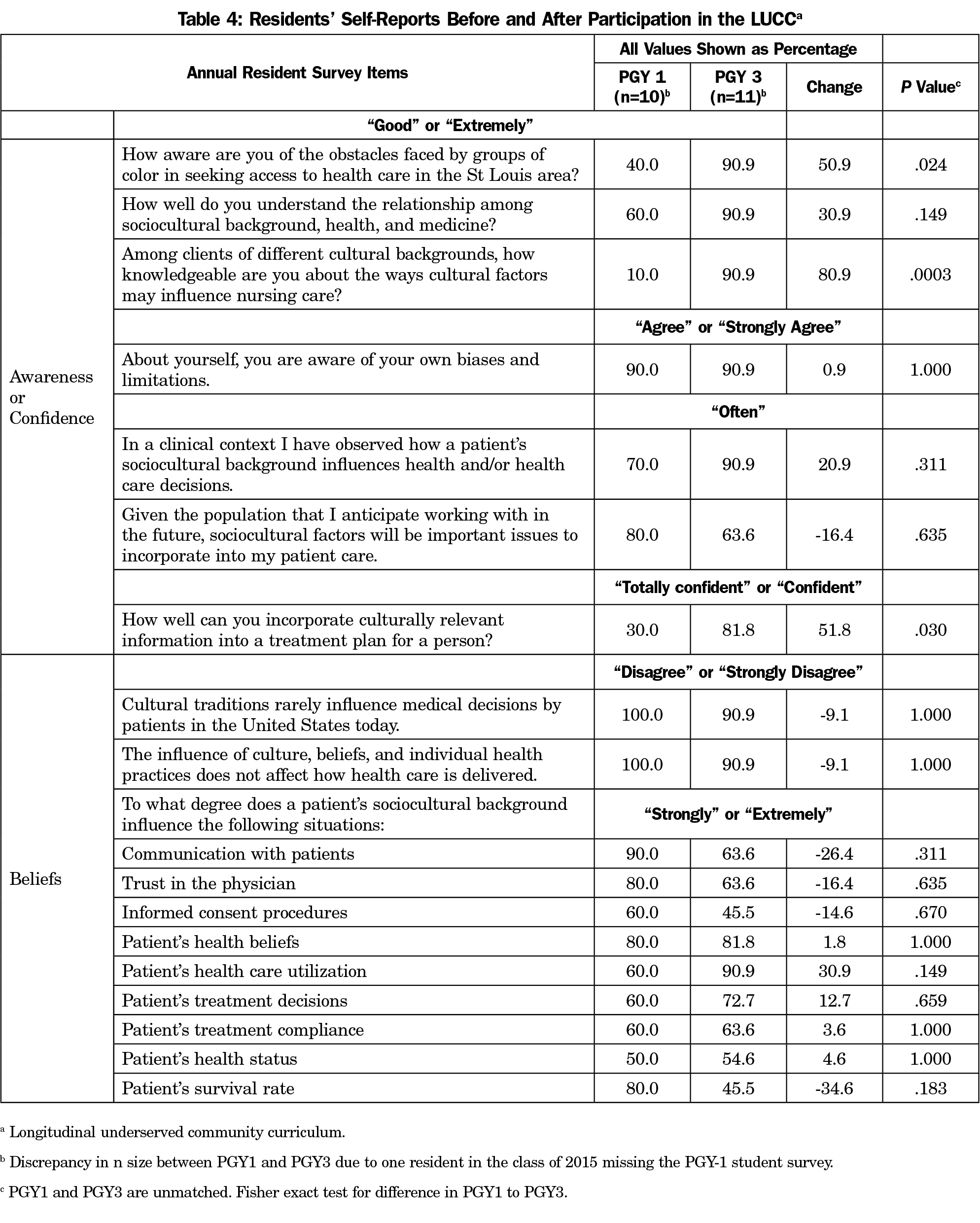

On the annual resident survey (Table 4), residents indicated greater awareness of cultural diversity and confidence in caring for people of diverse cultures from PGY1 to PGY3. Resident self-ratings of “good” or “extremely aware” of obstacles faced by groups of color seeking health care increased from 40.0% to 90.9% (P=.024), and of “good” or “extremely knowledgeable” of ways cultural factors may influence nursing care increased from 10.0% to 90.9% (P=.0003). The proportion of residents indicating “totally confident” or “confident” in incorporating culturally relevant information into a treatment plan significantly increased from 30.0% to 81.8% (P=.030). Resident responses regarding beliefs about the influence of socioeconomic and cultural factors on experiences with health care did not reach significance.

Curriculum Feedback

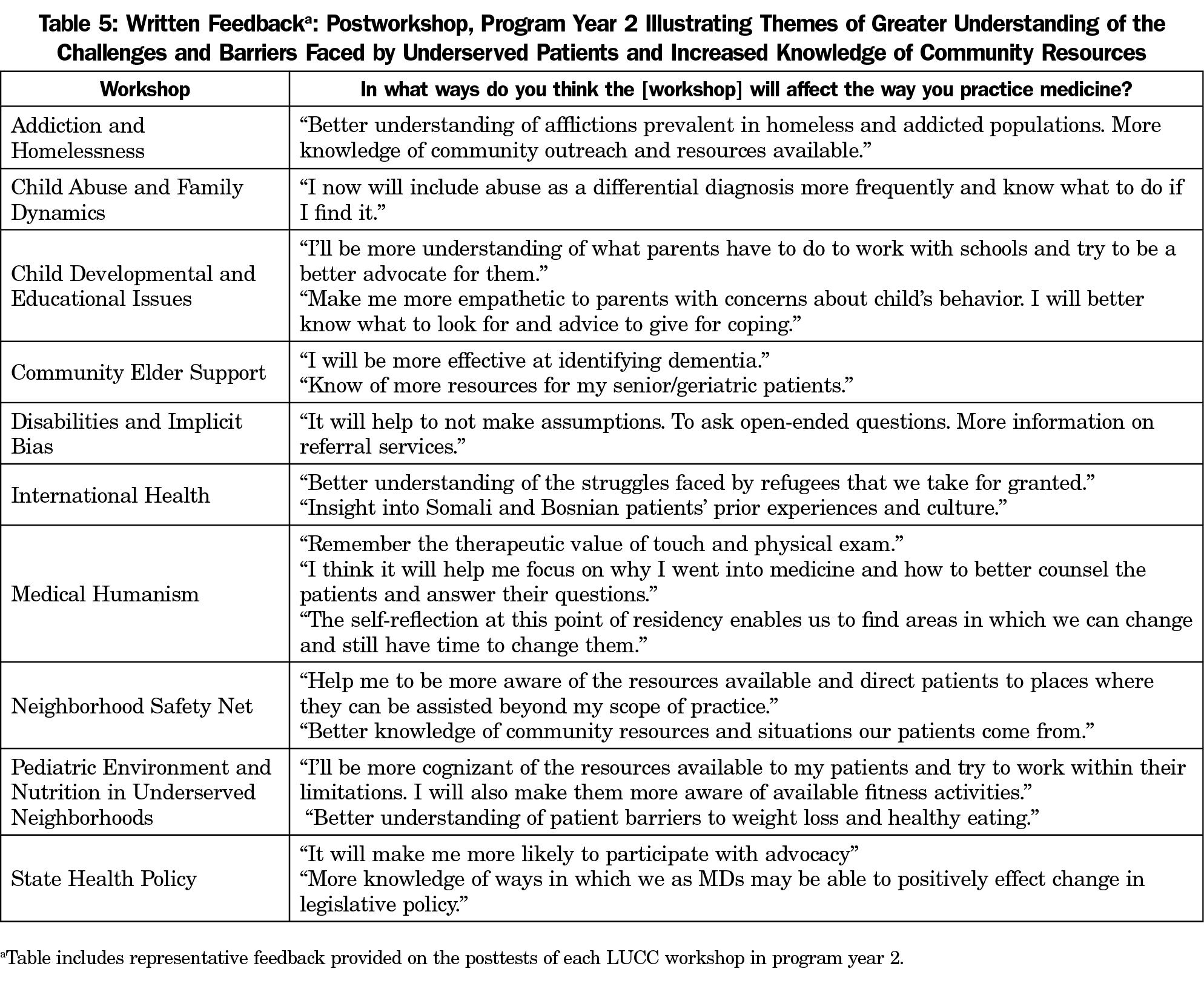

Two themes emerged from the authors’ review of resident written feedback after each workshop (representative comments in Table 5): greater understanding of the challenges and barriers faced by underserved patients, and increased knowledge of community resources.

Resident feedback in the workshop focus groups was used for faculty development and continuous curriculum quality improvement. Focus group feedback occasionally resulted in a minor workshop modification, and hospice was replaced with a disability workshop after one year. Residents frequently noted the value of immersion, as in comments such as “putting ourselves submerged into their situation… especially for the addiction and homelessness one, that was pretty like an eye-opener one for me.”

We implemented and evaluated a novel longitudinal curriculum to increase knowledge, awareness, and confidence in diverse underserved health care for residents practicing in an urban FQHC. A review of graduate medical education found few programs with structured block or longitudinal health disparities curricula, and a lack of consensus regarding content.14 In many residencies, the principles of underserved care are integrated into training and practice in a way that is not easily extracted.15 Our program is unique in its intentionality and longitudinal format that regularly reminded residents of the social determinants of health, provided meaningful experiences with faculty mentors in underserved care and complemented clinical experience with deepening understanding of a diverse population.

This study was limited by a small cohort size within a single residency program; findings may not be generalizable to other programs. Outcomes may have been influenced minimally by workshop adjustments after written and focus group feedback. The LUCC was implemented simultaneously with the beginning of the residency, and both have undergone continuous quality improvement. The positive change in resident cultural awareness and confidence on the annual surveys are likely from both the LUCC and practice in an FQHC. Changes in beliefs were not statistically significant and merit further investigation. However, pre- and post-LUCC surveys indicated significant knowledge gain attributable to individual sessions, and in focus groups, residents reiterated the value of immersion in issues such as homelessness, addiction, and refugee status in settings outside of FQHC practice. Although this curriculum was implemented in a family medicine residency with an urban underserved continuity practice, the experiential workshop format and the diversity of seminar topics are generalizable to other specialties and practice settings, with modification of content regarding local resources.

This study shows that a longitudinal underserved community curriculum can improve the knowledge, attitudes, and confidence of residents in an urban underserved residency. The next step is to implement and evaluate similar longitudinal curricula in diverse settings.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this curriculum, but not the current analysis, have been presented at 37th Forum for Behavioral Science in Family Medicine, Chicago IL, September 23, 2016, STFM Annual Spring Conference, Minneapolis MN, May 2, 2016, and the STFM Annual Spring Conference, Orlando FL, April 26, 2015.

Funding: This project was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number D58HP23229, Residency Training in Primary Care, total award amount: $652,421. This information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS, or the US Government.

References

- Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Park ER. Cultural competence and health care disparities: key perspectives and trends. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):499-505. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.499

- Betancourt JR. Cultural competence and medical education: many names, many perspectives, one goal. Acad Med. 2006;81(6):499-501. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ACM.0000225211.77088.cb

- Butler M, McCreedy E, Schwer N, et al. Improving Cultural Competence to Reduce Health Disparities [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016 Mar. (Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 170.) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK361126/. Accessed October 26, 2018.

- Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, et al. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):992-1000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2082-9

- Smith-Campbell B. A health professional students’ cultural competence and attitudes toward the poor: the influence of a clinical practicum supported by the National Health Service Corps. J Allied Health. 2005;34(1):56-62.

- Aeder L, Altshuler L, Kachur E, et al. The “Culture OSCE”—introducing a formative assessment into a postgraduate program. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2007;20(1):11.

- Schlotthauer AE, Badler A, Cook SC, Pérez DJ, Chin MH. Evaluating interventions to reduce health care disparities: an RWJF program. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(2):568-573. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.568

- Kachur EK, Altshuler L. Cultural competence is everyone’s responsibility! Med Teach. 2004;26(2):101-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590410001667427

- Godkin MA, Savageau JA. The effect of a global multiculturalism track on cultural competence of preclinical medical students. Fam Med. 2001;33(3):178-186.

- Jeffreys MR. A transcultural core course in the clinical nurse specialist curriculum. Clin Nurse Spec. 2002;16(4):195-202. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002800-200207000-00009

- Jeffreys MR, Smodlaka I. Construct validation of the Transcultural Self-Efficacy Tool. J Nurs Educ. 1999;38(5):222-227.

- Godkin M, Savageau J. The effect of medical students’ international experiences on attitudes

- Tang TS, Fantone JC, Bozynski MEA, Adams BS. Implementation and evaluation of an undergraduate sociocultural medicine program. Acad Med. 2002;77(6):578-585. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200206000-00019

- Hasnain M, Massengale L, Dykens A, Figueroa E. Health disparities training in residency programs in the United States. Fam Med. 2014;46(3):186-191.

- Strelnick AH, Anderson MR, Braganza S, et al. Health disparities training in residency programs in the United States. Fam Med. 2014;46(10):809-810.

There are no comments for this article.