Background and Objectives: Increasing the number of underrepresented minority (URM) physicians improves access and quality of care. URMs are more likely to practice primary care and work in underserved communities. The racial and ethnic diversity of family physicians lags behind the general population. To create a more diverse residency, the Boston Medical Center Family Medicine Residency Program (BMCFMRP) developed, implemented, and evaluated a strategic plan for diversity recruitment.

Methods: In academic year (AY) 2014-2015, we set goals to increase the number of URM applicants and the percentage of matched URMs. From 2014-2017, we implemented an intervention focused on: (1) increasing outreach to URM candidates, (2) revising interviews to minimize bias, and (3) analyzing recruitment data.

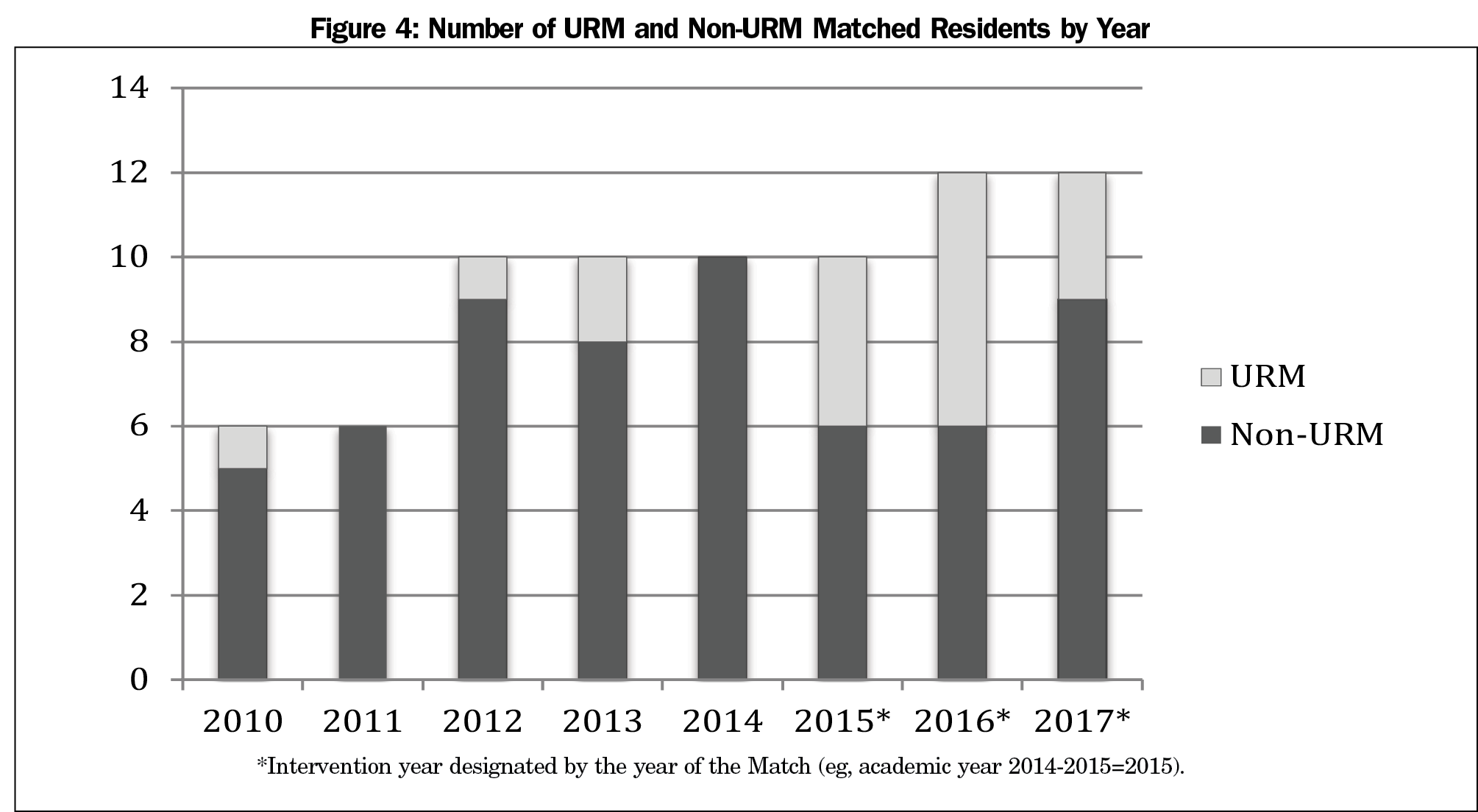

Results: From 2014-2017, the total number of URM applicants increased by 80% (61 to 110). Evaluating recruitment trends from 2010-2017, there was a statistically significant increase (P<0.001) in the percentage of URM applicants from 13.3% (29 of 218 total applicants) to 19.9% (110 of 402). There was also a significant increase (P=0.029) in the percentage of matched URMs. Before the intervention, the percentage ranged from 0% to 20% (2011: 0% [n=0/6], 2014: 0% [n=0/10], 2013: 20% [n=2/10]). During the intervention, the percentage ranged from 25% to 50% (2017: 25% [n=3/12], 2016: 50% [n=6/12]).

Conclusions: The implementation of a strategic plan for diversity recruitment increased the number of URM applicants and the percentage of URMs matching into the BMCFMRP. Additional research is needed to determine if these strategies produce similar results in residency programs at other institutions and in other medical specialties.

A diverse physician workforce promotes health equity.1 Currently racial and ethnic minorities comprise nearly 40% of the US population; however, individuals who identify as black, Hispanic, and Native American are designated underrepresented minorities (URM) in medicine because their representation in the physician workforce is less than that in the general population.2,3 In 2013, 8% of US physicians identified as URMs.

Increasing the number of URM physicians will improve access and quality of health care.4,5 URM physicians are more likely to practice primary care and work in underserved communities of color.6,7 Additionally, physician-patient racial or language concordance correlates to improved patient satisfaction and adherence.8,9

The diversity of family physicians has increased, but continues to lag behind the general population.10 In 2012, 9.4% of family medicine residents identified as Hispanic, 7.9% as black, and 0.9% as Native American.10 According to the American Academy of Family Physicians, “recruiting and retaining culturally diverse individuals into the field of family medicine is an important strategy to reduce disparities in health outcomes.”11 Despite the need for a more diverse family medicine workforce, to date there are no published studies that evaluate strategies for increasing the number of URMs in a family medicine residency program.

Boston Medical Center (BMC) is the largest safety-net hospital in New England. Seventy percent of patients come from underresourced populations and 60% of patient encounters involve patients identifying as black, Hispanic, Native American, or Native Hawaiian. Despite the diverse patient population, the racial and ethnic diversity of the BMC Family Medicine Residency Program (BMCFMRP) has historically been equal to or less than the national median. In academic year (AY) 2013-2014, 10.3% of residents identified as URMs. In the 2014 National Residency Match Program (NRMP), zero of the 10 matched interns identified as URMs. In response to the 2014 Match the author (M.H.W.), a URM resident passionate about minority representation in medicine, met with the program leadership to discuss strategies for increasing the number of URM residents. Within months, we began the development, implementation, and evaluation of a strategic plan for diversity recruitment.

In AY 2014-2015, a team comprised of the program director, associate program director, residency coordinator, and the author (M.H.W.) developed a strategic plan to increase the number of URMs who apply and match into the program. We conducted a literature search to identify examples of diversity recruitment strategies employed in medical schools and graduate medical education (GME). We also consulted the Office of Minority Physician Recruitment, an office in the BMC GME Department committed to the recruitment and advancement of URM residents and fellows. From 2014-2017, we implemented a stepwise intervention focused on: (1) increasing outreach to URM candidates, (2) revising interviews to minimize bias, and (3) analyzing recruitment data.

Increasing Outreach

In AY 2014-2015, we redesigned the program recruitment materials, emphasizing our commitment to underserved communities and featuring URM residents and faculty. We ensured that a URM resident or faculty member attended recruitment conferences focused on URM medical students and students interested in family medicine. Every URM candidate who interviewed met at least one URM resident and received a follow-up email from a URM resident or faculty member.

In AY 2016-2017 the director of diversity programs position, a 20% full-time effort (FTE) administrative role, was created by the chair of the Department of Family Medicine (DFM) and funded directly by Boston Medical Center with support of the hospital president and CEO. The position is an additional role for a faculty member with demonstrated interest and experience in the area of diversity recruitment. The primary responsibilities of the director are to lead the development, implementation, and evaluation of diversity recruitment efforts within the DFM and to work with the Office of Minority Physician Recruitment to create and disseminate recruitment best practices throughout the institution. The author (M.H.W.) filled the inaugural position upon graduating from residency and being hired as faculty.

Revising Interviews

Medical education studies demonstrate that interviewer bias can affect candidates’ interview scores.12 Each BMCFMRP candidate has four interviews (the program director, two faculty, one resident). Beginning in AY 2015-2016, one faculty and one resident interview were blinded, meaning the interviewer had no access to the candidate’s academic record. This helps eliminate the halo effect, in which the interviewer’s preconceptions based on scores influence the interview evaluation.12 Eliminating such bias is relevant given research showing that URMs traditionally score lower on the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) examinations.13 Structural racism has contributed to the overrepresentation of URM students in underperforming schools.14 Observed differences in test performance may also reflect stereotype threat.15 Stereotype threat occurs when individuals are at risk of confirming negative stereotypes about their group, such as the stereotype that racial and ethnic minority students score lower on standardized tests.15 Additionally, GME literature has questioned the utility of NBME scores in candidate evaluation.12,16 Step one scores may predict future examination scores, but do not necessarily correlate with a resident’s clinical performance.12,16,17

In AY 2016-2017, we continued blinded interviews and evolved to a structured interview format with each interviewer asking standardized questions reflecting the program’s mission and the characteristics valued in residents. While employment research has long supported structured interviews, medical education studies evaluating their use are limited and outcomes are mixed.18,19 Nonetheless, the American Association of Medical Colleges recommends structured interviews noting their greater reliability, validity, and equity.20

Analyzing Recruitment Data

Using the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS), we collected recruitment data before and during the intervention (AYs 2010-2017). We recorded annually the number of US and Canadian candidates, both URM and non-URM, who applied, interviewed, were ranked and matched into the program. Individuals who self-identified in ERAS as black, Hispanic, Native American or Native Pacific Islander were designated URMs.

We used the Cochran Armitage trend test to examine trends in the percentage of URMs who applied and matched into the program before and during the intervention. Analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 with P<0.05 considered statistically significant. The Boston University Institutional Review Board reviewed this project and deemed it exempt.

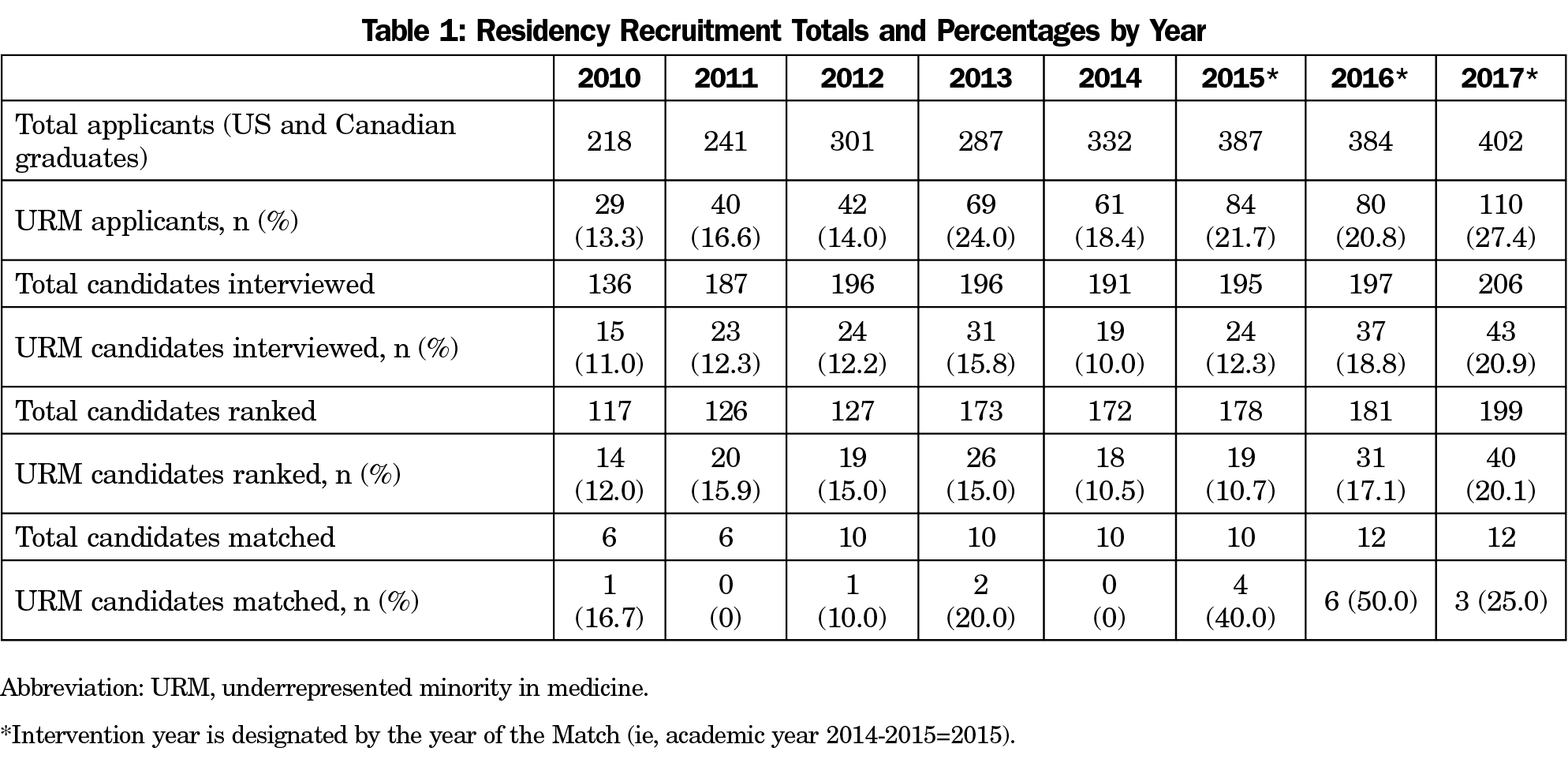

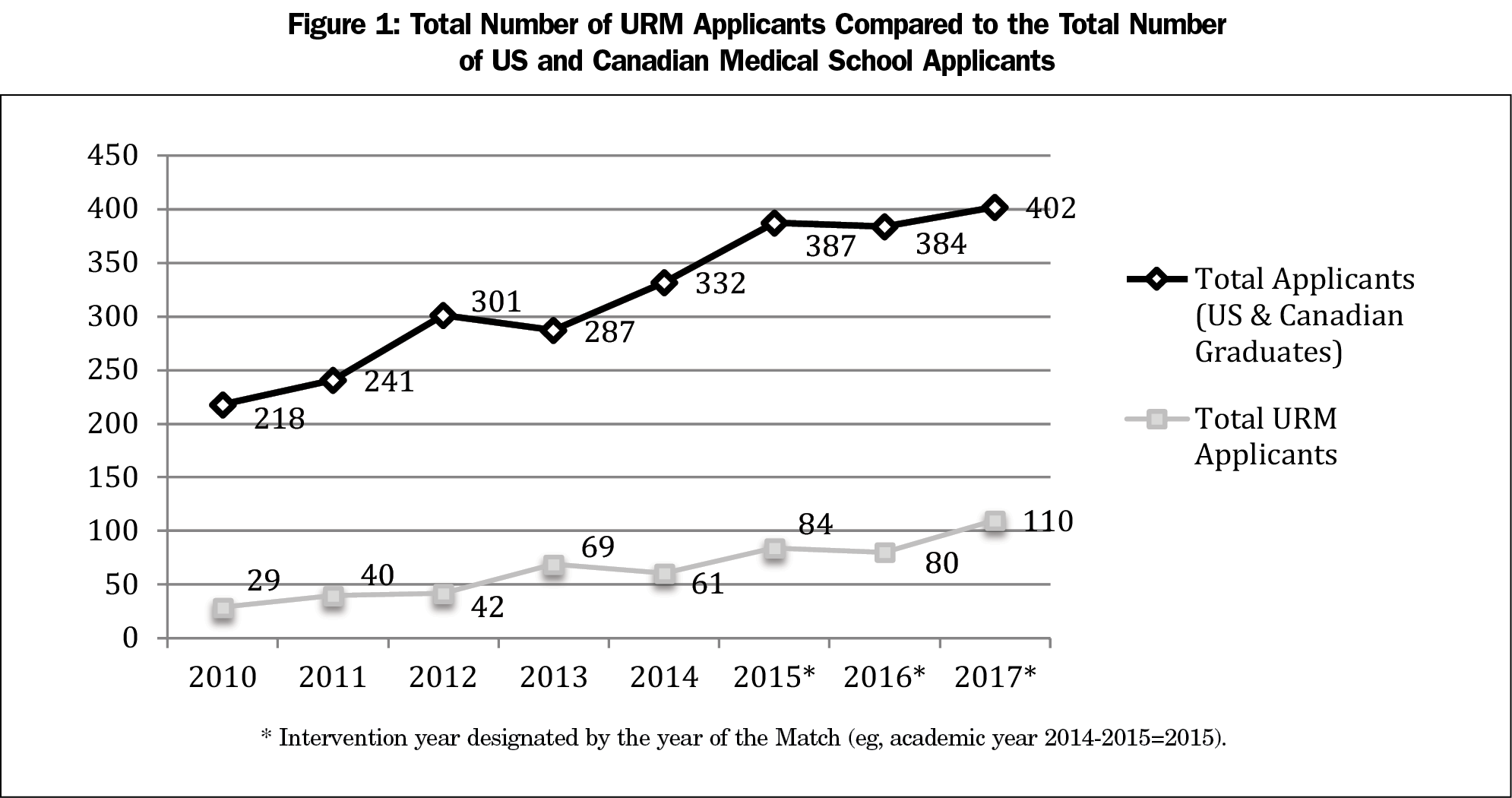

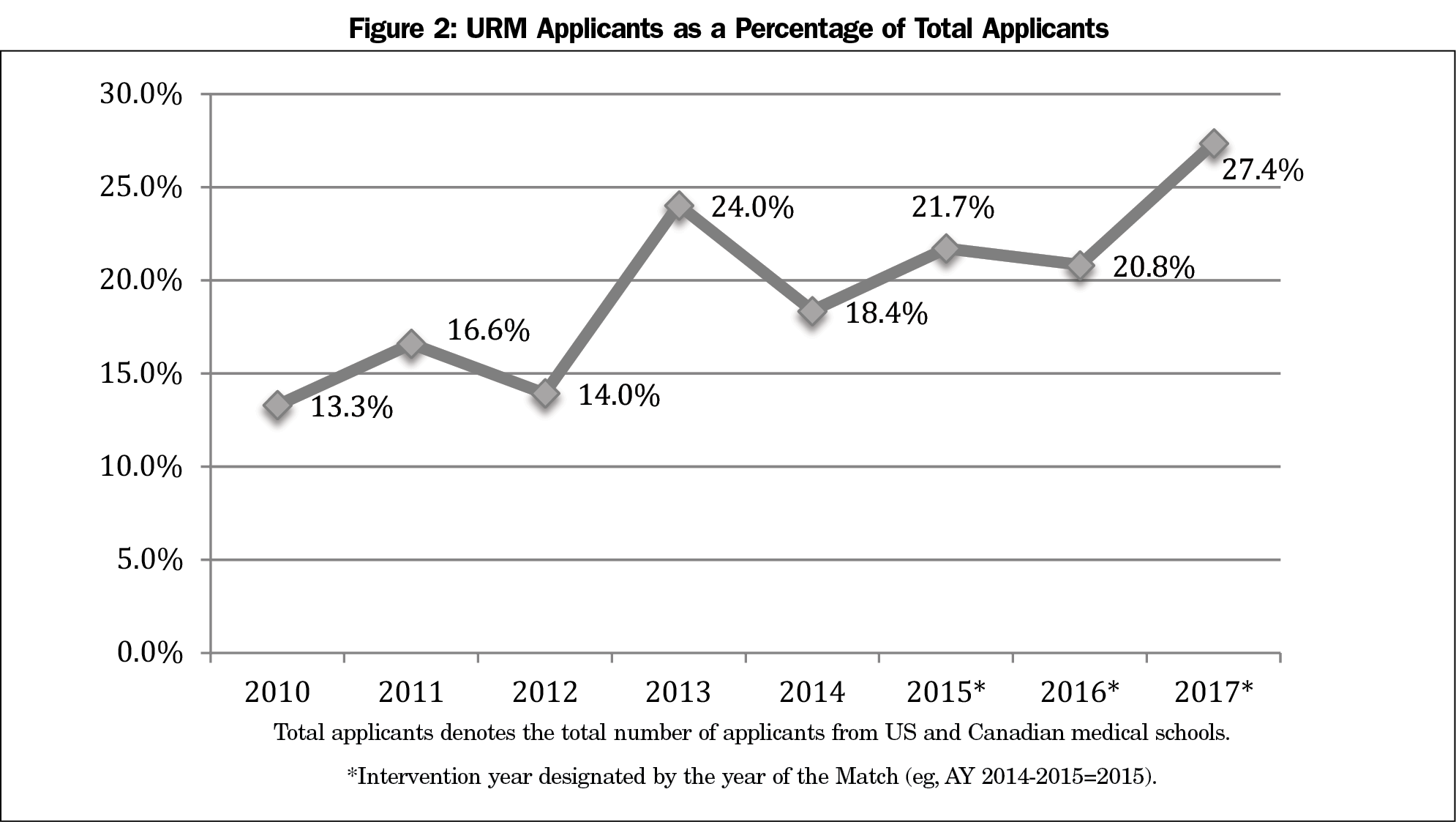

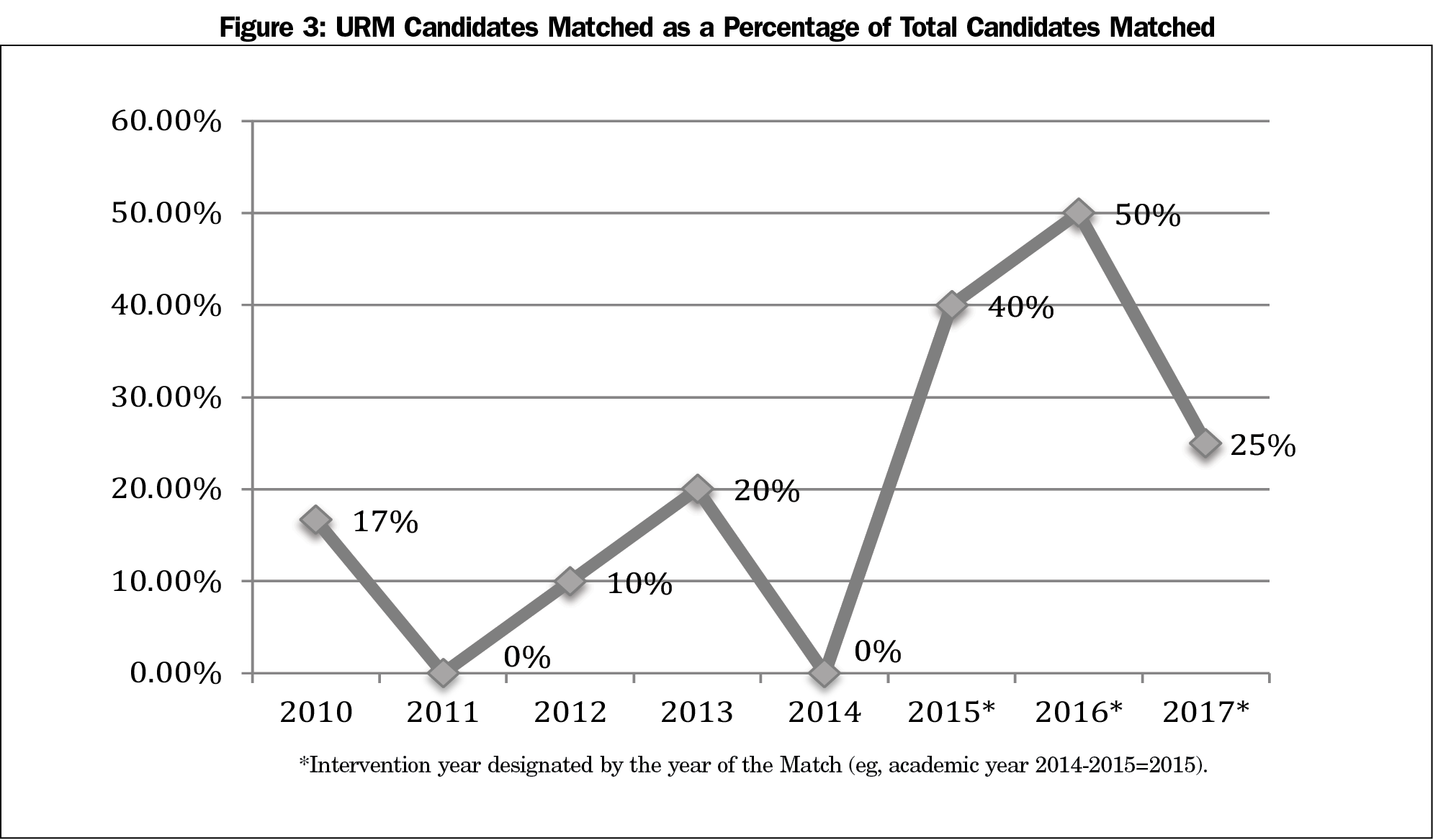

Table 1 describes recruitment data from AYs 2010-2017. During the intervention (AYs 2014-2017), the number of URM applicants increased by 80% (61 to 110, Figure 1). Evaluating recruitment trends from 2010-2017, there was a statistically significant increase (P<0.001) in the percentage of URM applicants from 13.3% (29 of 218 applicants) to 19.9% (110 of 402 applicants, Figure 2). There was also a significant increase (P=0.029) in the percentage of matched URM residents. Before the intervention, AYs 2010-2014, the percentage ranged from 0% to 20% (2011: 0% [n=0/6], 2014: 0% [n=0/10], 2013: 20% [n=2/10]). During the intervention, the percentage ranged from 25% to 50% (2017: 25% [n=3/12], 2016: 50% [n=6/12]; Figures 3 and 4).

In terms of the racial and ethnic identities of the matched URMs, in 2015 three of the matched interns identified as black and one identified as Hispanic. In 2016, five identified as black and one identified as Hispanic. In 2017, one intern identified as black and two identified as Hispanic.

The implementation of a strategic plan for diversity recruitment increased the total number of URM applicants and the percentage of URMs matching into the BMCFMRP. These results support previous research demonstrating that prioritizing diversity as a goal and implementing strategic interventions can lead to more diverse residency programs.21,22,23

We encountered challenges during the implementation of the diversity recruitment strategies. To address questions from residents and faculty about the shift from our prior recruitment process, we began each recruitment season with a resident meeting and a faculty development workshop. During the resident meeting, we emphasized our commitment to diversity recruitment, reviewed the process for the upcoming year, and explained the reasoning behind the interventions. The faculty development workshop focused on the use of blinded and structured interviews to mitigate bias.

Central to the implementation and success of our strategic plan was the involvement of URM residents and faculty. Literature refers to the extra responsibilities placed on URMs in academic medicine, particularly related to diversity, as the “minority tax.”23 In order to decrease this burden, non-URM faculty assisted in the development of the revised recruitment processes. In addition, the participation of URM residents and faculty in additional recruitment activities was presented as optional, rather than an expectation. Most importantly, the creation of the Director of Diversity Programs position enabled the author (M.H.W.) to assume primary responsibility for the initiatives in an administrative role with protected time and compensation.

There are several methodological weaknesses to our evaluation. Data are observational. We cannot determine if our findings were due to the intervention. Other potential contributing factors include temporal changes in the characteristics of the candidates, the increased size of the intern class, the program reputation, and other nationwide recruitment trends. Since data are limited to a single residency, it is unknown if our results will generalize to other programs. Finally, individuals designing the plan were involved in evaluating and ranking candidates, possibly introducing observer bias.

Further evaluation of the BMCFMRP strategic plan for diversity recruitment should examine the effect of URM candidates’ rank-list position and factors affecting URM candidates’ program-ranking decisions. In addition, the 2014-2017 strategic plan did not address applicant screening and selection for interview. In AY 2017-2018, our team developed and implemented a holistic applicant review aimed at mitigating bias and promoting our program’s mission and values in the screening and selection process. The data related to this intervention will be collected, analyzed, and reported. Beyond the BMCFMRP, research is needed to determine if implementing these strategies produces similar results in residency programs in other locations and in other specialties. Future interventions should expand their focus to supporting URM residents, recruiting and retaining URM faculty, creating pipeline initiatives, and developing curricula on the history and continued effects of racism, bias, and discrimination in order to further promote health equity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the BMCFMRP Program Director, Dr Thomas Hines, and the program staff, Kathryn Whitley and Stella Rupia, for their input and assistance. The authors also thank Justin McCummings, from the Office of Minority Physician Recruitment, for his support throughout this process and Dr Bob Vinci for his aid in the conceptualization and completion of this manuscript. The authors acknowledge the leadership of the Department of Family Medicine and Boston Medical Center for their institutional support, and the residents who make the training program exceptional through their commitment to patients and the field of family medicine.

References

- Institute of Medicine. In the Nation’s Compelling Interest: Ensuring Diversity in the Health Care Workforce. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2004.

- USA Quickfacts from the US Census Bureau [Internet]. Available from: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html

- American Association of Medical Colleges. The status of the new AAMC definition on “underrepresented in medicine” following the Supreme Court’s decision in Grutter. https://www.aamc.org/download/54278/data/urm.pdf. Accessed February 13, 2018.

- Laditka JN. Physician supply, physician diversity, and outcomes of primary health care for older persons in the United States. Health Place. 2004;10(3):231-244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2003.09.004

- Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions. The rationale for diversity in the health professions: a review of the evidence. Rockville, MD: HHS (US); 2006.

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Fair MA. Analyzing Physician Workforce Racial and Ethnic Composition Associations: Physician Specialties (Part I). AAMC Analysis In Brief. 2014; 14(8).

- Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, Bor DH, McCormick D. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):289-291. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12756

- Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, et al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 1999;282(6):583-589. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.6.583

- Ngo-Metzger Q, Sorkin DH, Phillips RS, et al. Providing high-quality care for limited English proficient patients: the importance of language concordance and interpreter use. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(suppl 2):324-330. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11606-007-0340-z. Accessed February 25, 2018.

- Xierali IM, Hughes LS, Nivet MA, Bazemore AW. Family medicine residents: increasingly diverse, but lagging behind underrepresented minority population trends. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(2):80-81.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Cultural Proficiency: The Importance of Cultural Proficiency in Providing Effective Care for Diverse Populations (Position Paper) [Internet]. 2014 https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/cultural-diverse-populations.html. Accessed February 24, 2018.

- Smilen SW, Funai EF, Bianco AT. Residency selection: should interviewers be given applicants’ board scores? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(3):508-513. https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2001.109868

- Veloski JJ, Callahan CA, Xu G, Hojat M, Nash DB. Prediction of students’ performances on licensing examinations using age, race, sex, undergraduate GPAs, and MCAT scores. Acad Med. 2000;75(10)(suppl):S28-S30. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200010001-00009

- Laurencin CT, Murray M. An American crisis: the lack of black men in medicine. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4(3):317-321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0380-y

- Walton GM, Spencer SJ. Latent ability: grades and test scores systematically underestimate the intellectual ability of negatively stereotyped students. Psychol Sci. 2009;20(9):1132-1139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02417.x

- Lypson ML, Ross PT, Hamstra SJ, Haftel HM, Gruppen LD, Colletti LM. Evidence for Increasing Diversity in Graduate Medical Education: The Competence of Underrepresented Minority Residents Measured by an Intern Objective Structured Clinical Examination. J Grad Med Educ. 2010; 2(3):354-359. http://www.jgme.org/doi/abs/10.4300/JGME-D-10-00050.1. Accessed February 24, 2018.

- Petersdorf RG, Turner KS, Nickens HW, Ready T. Minorities in medicine: past, present, and future. Acad Med. 1990;65(11):663-670. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199011000-00001

- Campion MA, Palmer DK, Campion JE. A review of structure in the selection interview. Pers Psychol. 1997. 50(3):655–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1997.tb00709.x

- Stephenson-Famy A, Houmard BS, Oberoi S, Manyak A, Chiang S, Kim S. Use of the interview in resident candidate selection: a review of the literature. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(4):539-548. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-14-00236.1

- American Association of Medical Colleges. Best Practices for Conducting Residency Program Interviews. September 2016. https://www.aamc.org/download/469536/data/best_practices_residency_program_interviews_09132016.pdf. Accessed February 13, 2018.

- Pierre JM, Mahr F, Carter A, Madaan V. Underrepresented in medicine recruitment: rationale, challenges, and strategies for increasing diversity in psychiatry residency programs. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(2):226–32. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s40596-016-0499-x. Accessed February 25, 2018.

- Tunson J, Boatright D, Oberfoell S, Bakes K, Angerhofer C, Lowenstein S, et al. Increasing resident diversity in an emergency medicine residency program: a pilot intervention with three principal strategies. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):958–961. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000957

- Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9

There are no comments for this article.