Background and Objectives: Little is known about how the academic coaching needs of medical students differ between those who are racially, ethnically, and socially underrepresented minority (RES-URM) and those who represent the majority. This single-site exploratory study investigated student perceptions and coaching needs associated with a mandatory academic coaching program, and coaches’ understanding of and preparedness to address these potentially differing needs.

Methods: Coaching needs of second- and third-year medical students were assessed using two initial focus groups and two validation focus groups, one consisting of RES-URM students and the other majority medical students. Coaches were assessed using a cross-sectional self-administered survey designed to determine their perceptions of differing coaching needs of students

Results: Seven themes emerged from the student focus groups. Three of these reflected the coaching relationship, and four reflected the coaching process. RES-URM students expressed stress around sharing vulnerability that was not expressed among majority students. Sixty-eight percent of coaches expressed that RES-URM students would not have differing needs of their coaches. Coaches self-rated as being somewhat (45%), moderately (29%), or very (13%) skilled at coaching RES-URM students.

Conclusions: RES-URM students cite different coaching needs than majority students that most coaches do not recognize. Faculty and program development regarding these unique needs is warranted.

Approximately 81% of medical schools have programs designed to recruit underrepresented minority students to diversify the student body toward serving diverse and underserved populations.1,2 As a result, the racial profile of US medical school enrollees has shifted, with 46.9% identifying themselves as nonwhite in 2016/2017.3,4 While programs dedicated to matriculation of minority students appear well established, and many medical schools offer prematriculation programs for students with diverse backgrounds,5-8 less in known about what is needed to help them succeed once enrolled.

Academic coaching has been used in undergraduate education and elsewhere9-14 to enhance performance. Coaching is emerging as a new model to prepare learners in competency-based medical education.9,15 In a prior study, we defined academic coaching as a developmental process whereby an individual learner meets regularly over time with a faculty coach to create goals, identify strategies to manage existing and potential challenges, improve academic performance, and develop professional identity toward reaching the learner’s highest potential.16 Thus, academic coaching, which differs from mentoring and advising in that it is learner driven and emphasizes individualized goals, could meet minority medical students’ needs in particular.14,16-18

In this mixed-methods study, we examined how perspectives and coaching needs of medical students differ between RES-URM and majority medical students, and assessed coaches’ awareness of potential differences among these student groups.

Oregon Health & Science University’s (OHSU’s) mandatory coaching program is comprised of clinician-educator MD coaches, who receive regular faculty development and are assigned to all medical students. Coaching meetings occur every 6 weeks, where student’s e-portfolios are reviewed, academic goals are created, and approaches for meeting goals are discussed. Students also meet with their coach in small groups to explore professional identity topics.

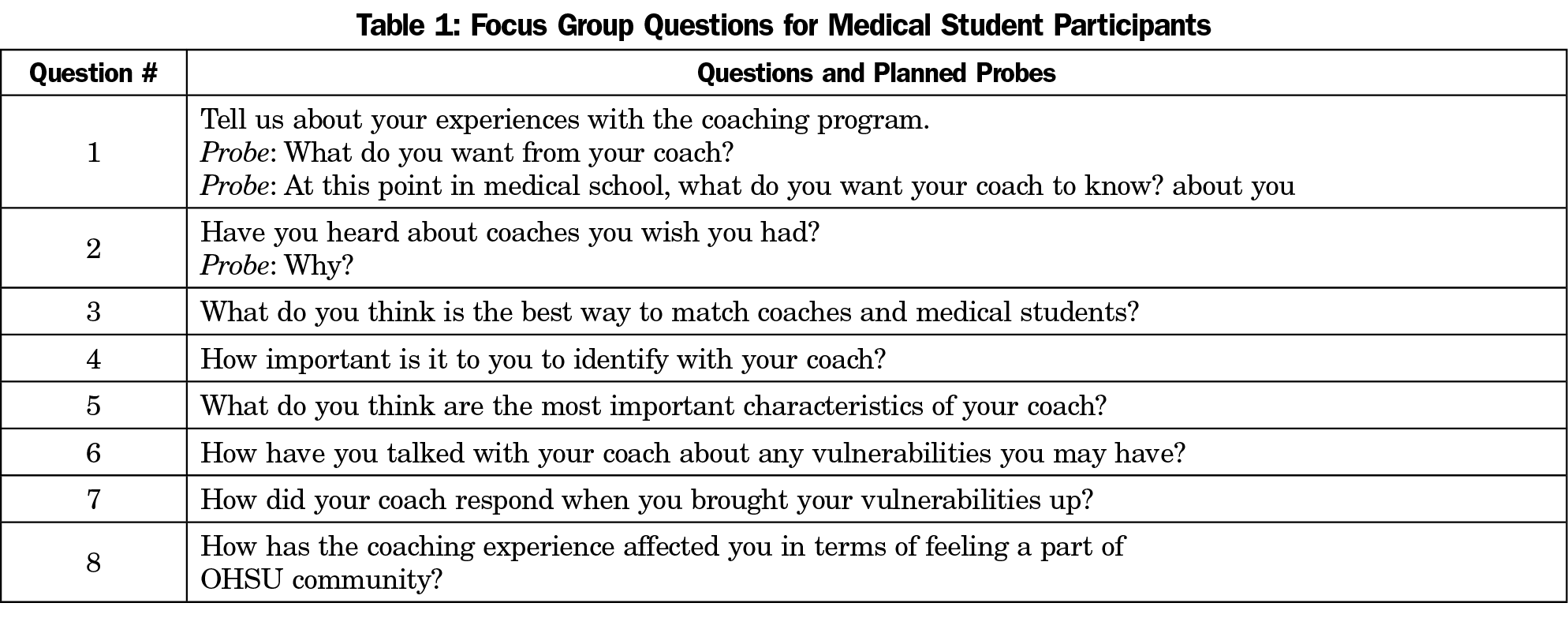

OHSU’s Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved all study activities (IRB# 16147). For focus groups, all second- and third-year medical students in the graduating classes of 2018 and 2019 were invited (n=280). Targeted recruitment for URM students was done with the assistance of the Center for Diversity and Inclusion’s Student Interest Groups and the student council. The first 20 who responded (10 in the URM group and 10 in the non-URM group) were enrolled. RES-URM were defined as members of racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic groups, including diversity in economic, sexual orientation, or disability status that are underrepresented in medicine relative to local and national demographics.19 Four focus groups were held, two initial sessions, one each with RES-URM and majority students, both of which addressed questions included in Table 1, and were facilitated by an experienced investigator. After initial qualitative data analyses were complete, validation focus groups were held with each group to share findings and assess reactions.

All faculty coaches from OHSU’s coaching program (n=33) were invited to complete an 11-item online deidentified survey that was pilot tested,20 then administered in November 2016.

Data Analysis

Analyses of focus group data involved open and axial coding of field notes by two independent investigators using constant comparative analyses and immersion crystallization techniques.21,22 Emergent themes were identified and defined, and exemplars selected using consensus meetings. Findings were presented at the validation focus groups and only minor revisions were applied. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize coaches’ survey responses.

Medical Student Results

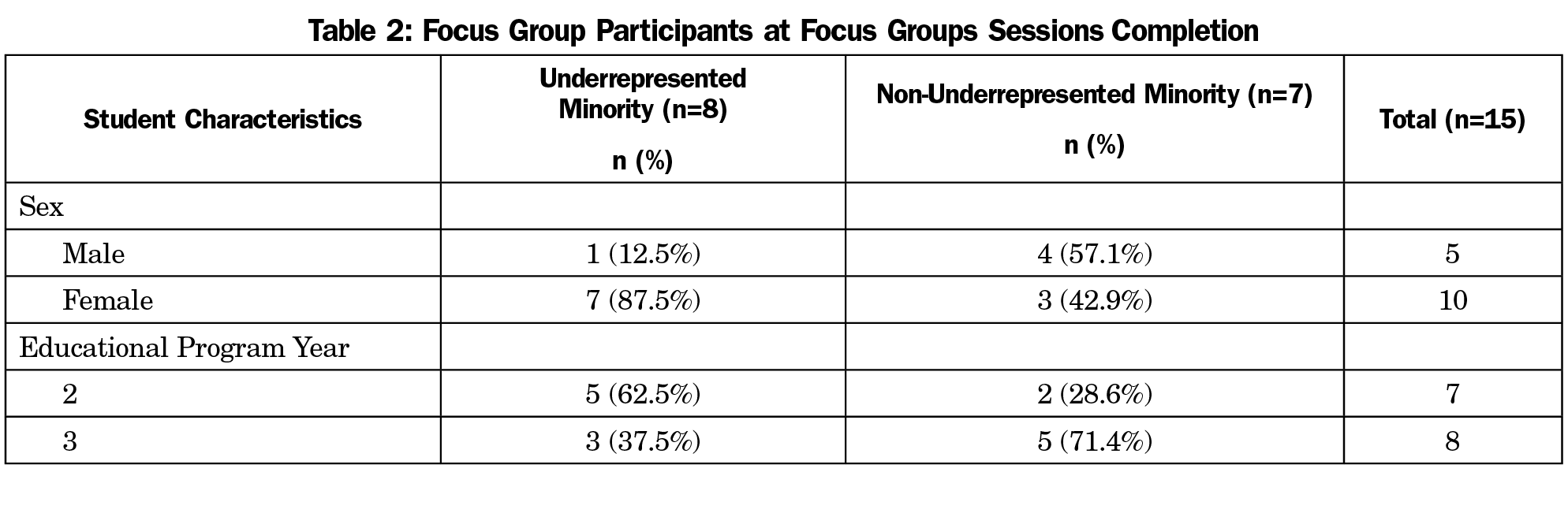

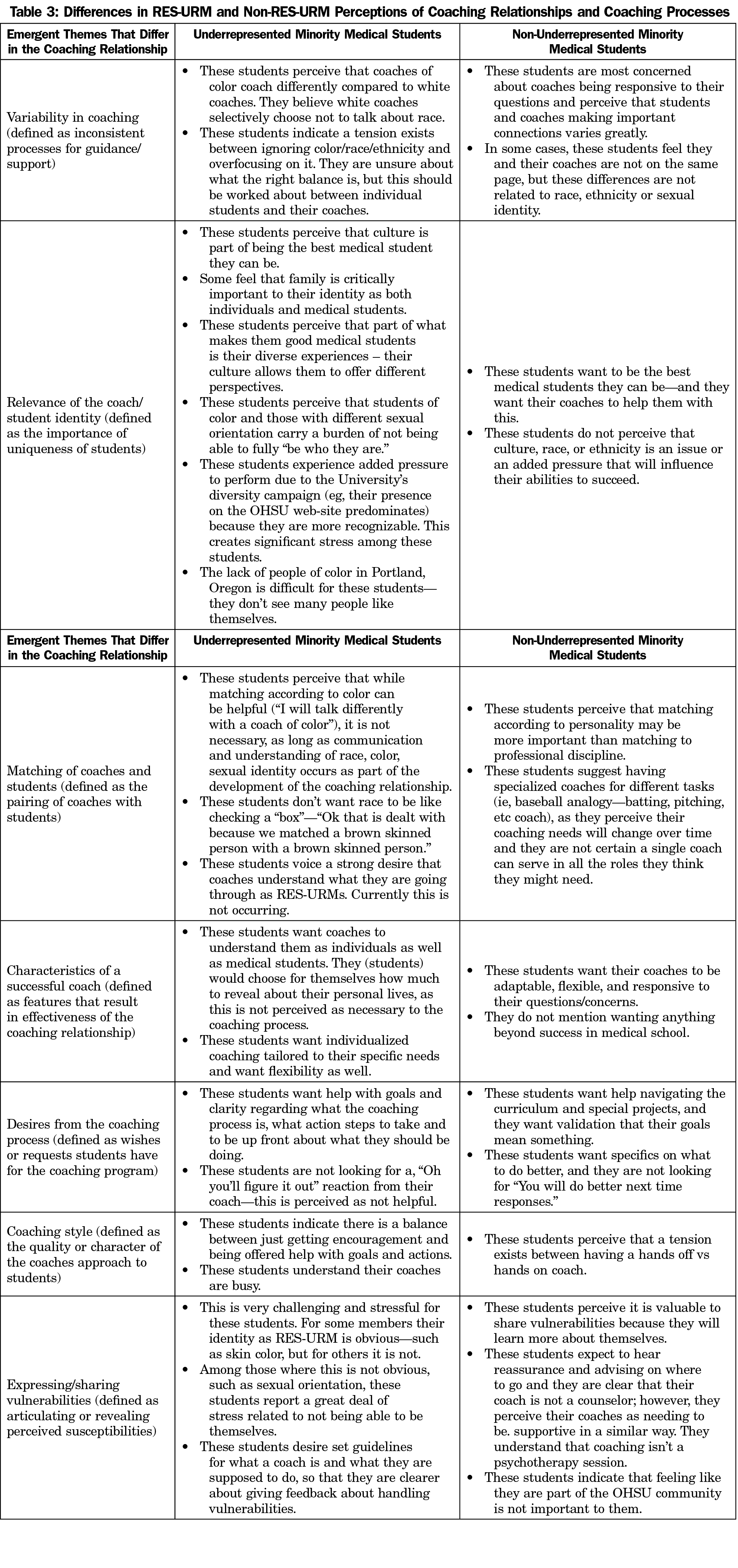

Focus group participants’ demographics are summarized in Table 2. Seven themes emerged from the focus groups: three regarding the coaching relationship, and four centering on coaching processes (Table 3). Regarding the relationship, RES-URM students voiced tension around coaches not overly focusing on race while also not ignoring it. RES-URM students perceive they experience greater pressure to succeed because they are the school’s face of diversity. RES-URM students indicated it was less important to have a coach identify as RES-URM than to have a coach who understands the importance of culture and how it might affect the coaching relationship and processes.

Regarding the process, while majority students perceived that sharing vulnerabilities would help them learn more about themselves, RES-URM students reported sharing vulnerabilities is very stressful for them (Table 3). RES-URM students preferred to have set guidelines about the coaching relationship and processes to help them decide how to handle their vulnerabilities and related stressors.

Coaches Results

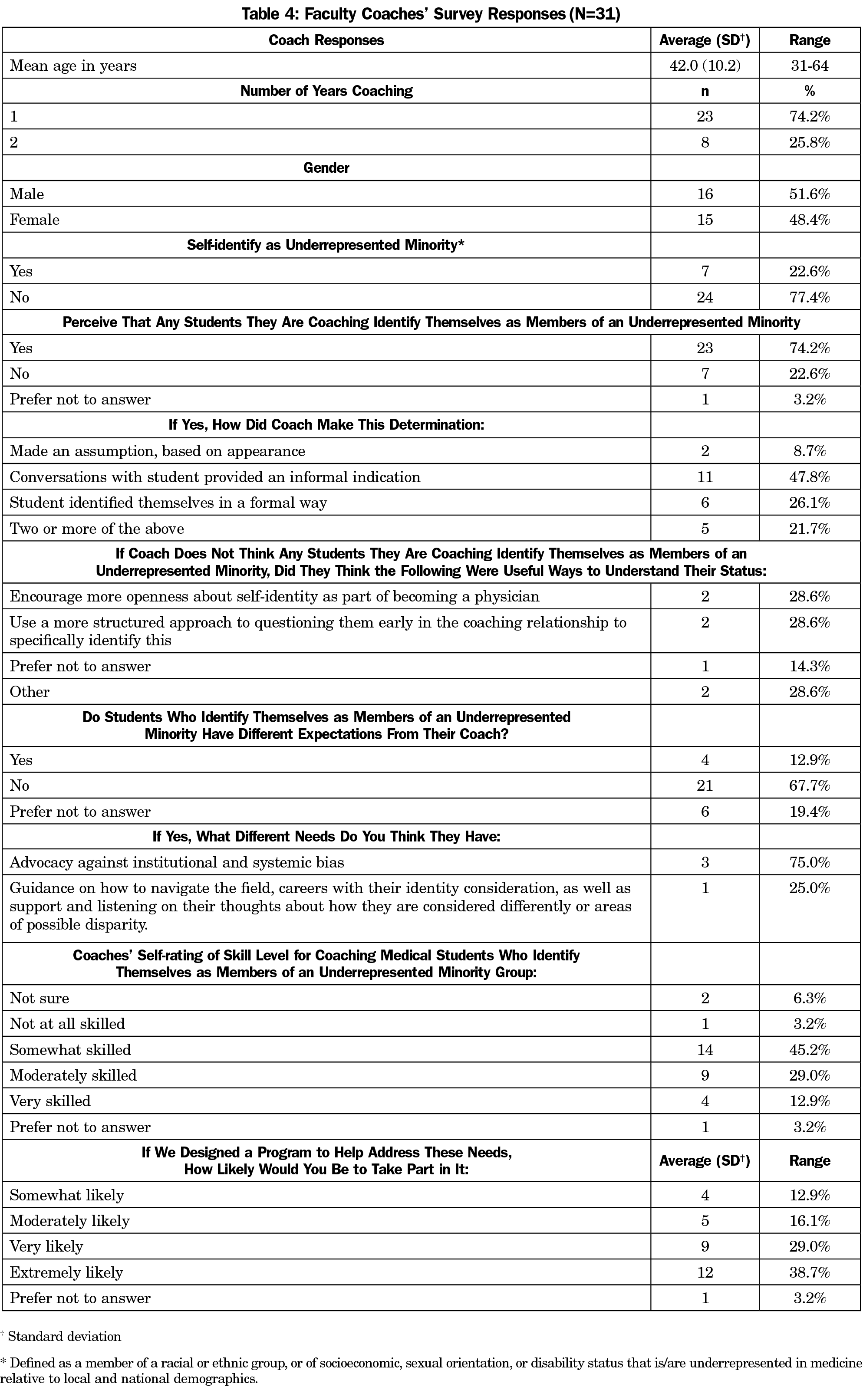

Thirty-one of 33 (93.9%) coaches completed the survey (Table 4). Seven (22.6%) self-identified as RES-URM, a number too small for meaningful comparisons. Twenty-one coaches (67.7%) perceived that RES-URM students would not have different needs than majority students. When asked to rate their skill in coaching RES-URMs, many (45.2%) reported being somewhat skilled. Only 4 (12.9%) reported being very skilled. Most (67.7%) reported being very/extremely likely to participate in programs to help address RES-URM medical students’ needs.

Several novel findings emerged from this exploratory research. Recent studies on improving RES-URM medical student performance focus only on academic outcomes, with none aimed at improving the learning environment experienced by RES-URM students.23 We found that RES-URM students desire more environmental context to academic coaching and desire a coach who acknowledges the context of a student’s culture in their academic achievement. Majority students did not report culture, race, ethnicity, or sexual orientation as barriers to the coaching relationship and processes, in contrast to RES-URM students. Sharing vulnerabilities was very stressful for RES-URMs. As coaching programs are designed to examine students’ gaps and areas for improvement, this perception may undermine the primary goal of coaching. In addition, we are concerned with how differences in URM/non-URM affect the process of professional identity formation—an area ripe for future research.

Also striking is the finding that coaches perceive that the needs and expectations of RES-URM students are not substantially different from majority students. If coaching program developers share this view, any coaching program could be developmentally flawed. Professional development for educators should include meaningful interactions between them as faculty and social, cultural and structural working environments.24, 25 Such professional development requires self-reflection and vulnerability, which in turn allows modeling of learner vulnerability.24 Creating a safe learning environment is critical. If RES-URM students feel at risk when sharing vulnerabilities, their professional development could be hindered.

Our study was exploratory due to its size and single-site design. Students and faculty who participated may have differing perceptions of academic coaching, which could have affected our findings.

Our study suggests that RES-URM medical students have different coaching needs compared to majority students, a fact that was unappreciated by coaches. These findings have implications for UME leaders and coaching and diversity programs, and warrant further investigation into the best way to achieve optimal coaching outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Dean’s Office at Oregon Health & Science University via an Accelerating Change in Medical Education Grant from the American Medical Association and by the Research Program in Family Medicine.

References

- Sokal-Gutierrez K, Ivey SL, Garcia RM, Azzam A. Evaluation of the Program in Medical Education for the Urban Underserved (PRIME-US) at the UC Berkeley-UCSF Joint Medical Program (JMP): The First 4 Years. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27(2):189-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2015.1011650

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Results of the 2015 Medical School Enrollment Survey: April, 2016. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/2015_Enrollment_Report.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2017.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Table B-5: Total Enrollment by US Medical School and Race/Ethnicity: 2016-2017. https://www.aamc.org/download/321540/data/factstableb5.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2017.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical School Enrollment Shows Diversity Gains: October, 2010. https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/newsreleases/2010/152932/101013.html. Accessed June 2, 2017.

- Grumbach K. Commentary: adopting postbaccalaureate premedical programs to enhance physician workforce diversity. Acad Med. 2011;86(2):154-157. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182045a68

- Alexander C, Chen E, Grumbach K. How leaky is the health career pipeline? Minority student achievement in college gateway courses. Acad Med. 2009;84(6):797-802. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a3d948

- Wilson WA, Henry MK, Ewing G, et al. A prematriculation intervention to improve the adjustment of students to medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2011;23(3):256-262. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2011.586923

- American Medical Association. AMA Continues Innovative Initiative to Reshape Medical https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/ama-continues-innovative-initiative-reshape-medical-education. Published April 13, 2013. Accessed September 9, 2017.

- Knowles MS. The Modern Practice of Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Andragogy. Cambridge: Prentice Hall Regents; 1970.

- Cummings TG, Worley CG. Coaching and Mentoring (in) Organizational Development and Change. Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning; 2009.

- Gawande A. Personal best. The New Yorker. September 26, 2011. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2011/10/03/personal-best. Accessed July 11, 2016.

- Gazelle G, Liebschutz JM, Riess H. Physician burnout: coaching a way out. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(4):508-513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3144-y

- Gifford KA, Fall LH. Doctor coach: a deliberate practice approach to teaching and learning clinical skills. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):272-276. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000097

- Sargeant J, Lockyer J, Mann K, et al. Facilitated reflective performance feedback: developing an evidence- and theory-based model that builds relationship, explores reactions and content, and coaches for performance change (R2C2). Acad Med. 2015;90(12):1698-1706. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000809

- Williams SN, Thakore BK, McGee R. Providing social support for underrepresented racial and ethnic minority PhD students in the biomedical sciences: a career coaching model. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2017;16(4):ar64. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-01-0021

- Deiorio NM, Carney PA, Kahl LE, Bonura EM, Juve AM. Coaching: a new model for academic and career achievement. Med Educ Online. 2016;21(1):33480. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v21.33480.

- Schumacher DJ, Englander R, Carraccio C. Developing the master learner: applying learning theory to the learner, the teacher, and the learning environment. Acad Med. 2013;88(11):1635-1645. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a6e8f8

- Li ST, Paterniti DA, Co JP, West DC. Successful self-directed lifelong learning in medicine: a conceptual model derived from qualitative analysis of a national survey of pediatric residents. Acad Med. 2010;85(7):1229-1236. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181e1931c

- Page KR, Castillo-Page L, Poll-Hunter N, Garrison G, Wright SM. Assessing the evolving definition of underrepresented minority and its application in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2013;88(1):67-72. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318276466c

- Beatty PC, Willis GB. Research synthesis: the practice of cognitive interviewing. Public Opin Q. 2007;71(2):287-311. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfm006

- Miller WL, Crabtree BF. The Dance of Interpretation. Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1999:127-143.

- Cohen DJ, Crabtree BF. Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: controversies and recommendations. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):331-339. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.818

- Orom H, Semalulu T, Underwood W III. The social and learning environments experienced by underrepresented minority medical students: a narrative review. Acad Med. 2013;88(11):1765-1777. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a7a3af

- Kelchterman G. Who I am in how I teach is the message: self-understanding, vulnerability and reflection. Teachers Teach: Theor Pract. 2009;15(2):257-272. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600902875332

- Bell S. Self-reflection and vulnerability in action research: bringing forth new worlds in our learning. Syst Pract Action Res. 1998;11(2):179-191. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022981402690

There are no comments for this article.