Background and Objectives: Faculty vacancies are a concern for chairs of academic family medicine departments who regularly face having to recruit new faculty. Faculty physicians who report lack of support for research and teaching or excessive time in activities that are not meaningful may experience burnout resulting in leaving academic medicine.

Methods: Data were collected via a Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of US family medicine department chairs. To determine characteristics associated with success in hiring new physician faculty, chairs answered questions about the number of vacancies in the previous 12 months, the number of vacancies filled in the previous 12 months, the months the longest vacancy was open, starting salary, whether signing bonus was offered, and the full-time equivalent (FTE) for clinical, research, teaching, and administrative time.

Results: The response rate was 52%. Chairs reported an average of 3.9 vacancies in the previous 12 months, and an average of 2.5 (66%) were filled. Chairs who didn’t offer protected time for teaching filled a higher percentage of their vacancies, but they did not fill them faster than departments that did offer teaching time. Higher salary and a signing bonus were associated with filling positions faster. Chairs who offered a signing bonus filled positions nearly 4 months sooner than those who didn’t.

Conclusions: Offering protected time for teaching or research and FTE allocation for clinical, teaching, research, and administrative time were not associated with success in hiring new faculty. Chairs who offered higher salaries and signing bonuses were able to hire faculty more quickly than those who didn’t.

Faculty vacancies are a concern for chairs of academic family medicine departments, with one study finding that 30% of family medicine faculty left their positions over a 3-year period.1 This turnover rate can translate to department chairs regularly having to recruit new faculty to fill nearly constant vacancies. In response to this crisis, the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) Foundation developed an initiative (Faculty for Tomorrow), that is a series of workshops and webinars designed to support the training, recruitment, and retention of family medicine faculty.2

One approach to understanding the reasons for faculty vacancies is to explore why faculty leave academic medicine. Faculty physicians who spend excessive time in activities that are not perceived as meaningful may experience burnout that can lead to their leaving academic medicine.3,4 Reasons for burnout include lack of staff support,5 insufficient time for documentation, lack of teaching support,6 balancing competing demands, and lack of protected research time.7

Predictors of faculty intention to leave a job include spending too much time on patient care and administrative activities.8 Newly hired faculty who resign cite poor climate for teaching and research, and having greater than 50% of their time dedicated to clinical care.9 Certain characteristics of faculty positions, including full-time equivalent (FTE) distribution and availability of resources, can lead to job dissatisfaction, which in turn can lead to physician faculty attrition. However, it is unknown if these same characteristics are barriers to hiring physician faculty. We hypothesized that the characteristics that lead to faculty burnout and attrition contribute to the challenges of hiring new faculty. The purpose of this study was to determine whether offering protected time for teaching and research was associated with success in hiring new faculty and whether FTE allocated for clinical, teaching, research, and administrative time was related to length of time to hire new faculty.

Questions about family physician faculty vacancies and hiring were asked as part of a larger omnibus survey conducted by the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA).10 The CERA steering committee evaluated questions for consistency with the overall subproject aim, readability, and existing evidence of reliability and validity. Pretesting was done on family medicine educators who were not part of the target population. Questions were modified following pretesting for flow, timing, and readability. The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved the project in March, 2018. Data were collected from March to May, 2018.

The sampling frame for the survey was all Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education-accredited US family medicine residency program directors identified by the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors (AFMRD) and US family medicine department chairs identified by the Association of Departments of Family Medicine (ADFM). Invitations to participate were emailed with the survey link utilizing the online program SurveyMonkey. We sent five follow-up emails to encourage nonrespondents to participate after the initial email invitation.

To reduce redundant responses for the number of faculty vacancies, we only used data from the department chairs. There were 149 department chairs at the time of the survey. Four emails could not be delivered therefore the final sample size for department chairs was 145. Seventy-five department chairs responded to the survey, resulting in a 51.7% response rate.

Survey Questions

For both full- and part-time clinical physician faculty positions, respondents answered questions about the number of vacancies their departments had in the previous 12 months, the number of vacancies filled in the previous 12 months, and the number of months the longest vacancy was open. For the most recent position filled, we asked how many months the position was open, the rank of the position, first-year salary, whether signing bonus was offered, and the FTE for clinical, research, teaching, and administrative time.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics summarized the study variables. We calculated the percentage of vacancies filled by dividing the number of vacancies filled in the previous 12 months by the number of vacancies a department reported in the previous 12 months. We used independent samples t-tests to determine associations between the percentage of vacancies filled and whether or not departments offered protected time for teaching, protected time for research, and a signing bonus. Independent samples t-tests were also used to determine the association between the number of months the longest full-time vacancy was open and whether or not departments offered protected time for teaching, protected time for research, and a signing bonus. Only data from department chairs who reported clinical physician vacancies in the previous 12 months were used for these analyses.

For the most recent clinical physician hire, bivariate correlations determined associations between the number of months the position was open and the salary, FTE for clinical, FTE for teaching, FTE for research, and FTE for administrative/other that was given to the new hire. We used an independent samples t-test to determine associations between the number of months the position was open and whether the new hire was given a signing bonus. Data used for analyses included only those where FTE for the most recent hire totaled 1.0 or less.

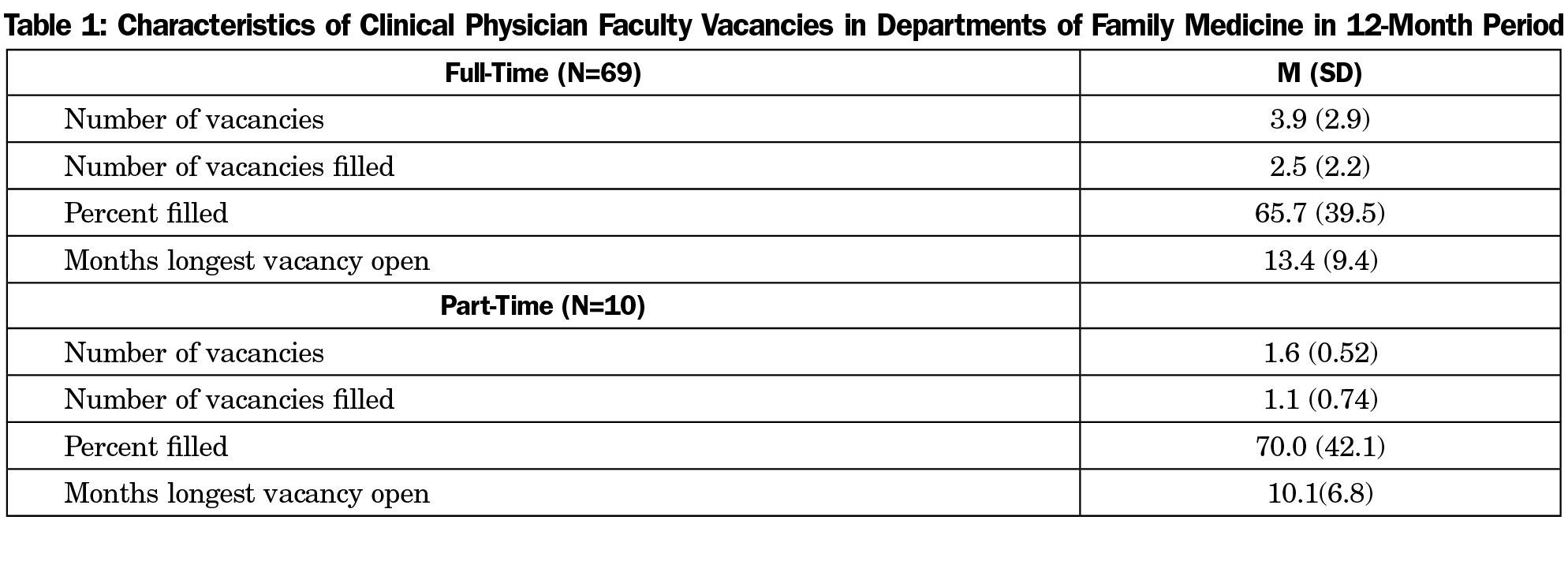

For full-time clinical faculty physician positions, family medicine departments had an average of 3.9 vacancies in the previous 12 months, and these departments filled an average of 2.5 (66%) of their vacancies. The position that was open the longest was vacant for an average of 13.4 months. Just 10 departments reported part-time vacancies during the last 12 months, with an average of 1.6 vacancies of which 1.1 (70%) were filled (Table 1).

Most departments offered protected time for teaching (81%). Less frequent incentives for new hires were signing bonuses (49%) and protected time for research (28%). T-tests revealed departments that offered protected time for teaching filled 61% of their vacancies vs 85% for departments that didn’t offer protected time for teaching (P=.002). Offering protected time for research or a signing bonus did not affect the percentage of vacancies filled. Offering protected time for research, protected time for teaching, and a signing bonus did not affect the duration of vacancy for the longest-open position.

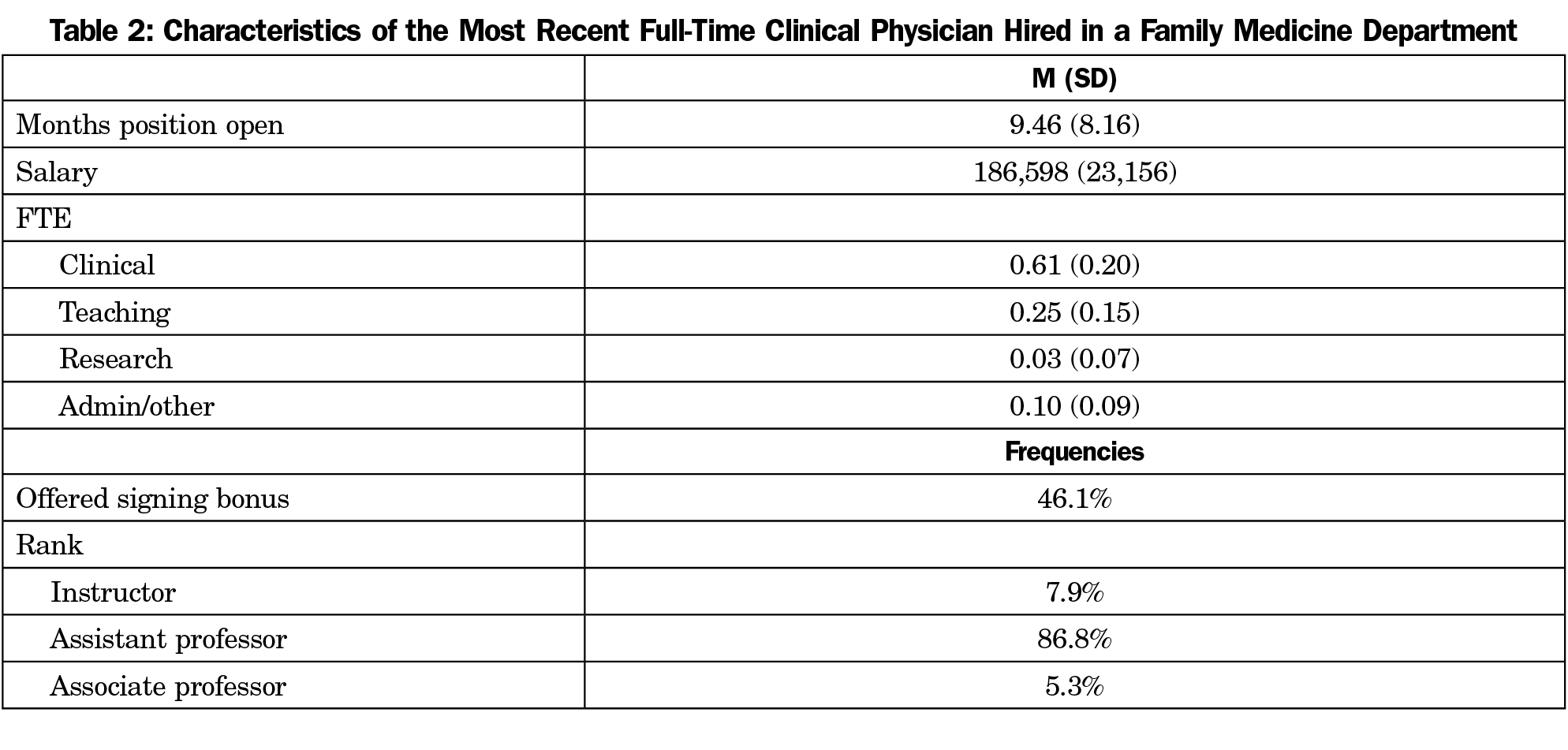

Department chairs stated that the most recent clinical physician faculty hired was usually at the assistant professor level, and was offered an average salary of $186,600 (Table 2). Bivariate correlations revealed an inverse relationship between the salary offered for the most recent hire and the number of months the position was open (r=-0.26, P=.024). An independent samples t-test showed departments that offered a signing bonus to their most recent hire filled the vacancy in fewer months than those departments that didn’t offer a signing bonus (7.5 months [SD=4.7] vs 11.2 months [SD=10.0]; P=.038). There were no significant correlations between the FTE for clinical, teaching, research, or administrative time and the number of months the position was open.

To determine factors associated with success in hiring clinical physician faculty, we examined what departments typically offer to recruit new faculty, and we also explored characteristics of the most recent clinical physician faculty hired. We operationalized success in hiring as percent of vacancies filled and the number of months a position was vacant. Departments were only able to fill two-thirds of their vacancies, which provides support for the faculty shortage concern. Although lack of support for teaching and research contribute to burnout among current faculty6,7 and faculty leaving a position,9 these were not associated with success in hiring faculty in our study. Most departments offered protected time for teaching. Interestingly, departments that didn’t offer protected time for teaching filled a higher percentage of their vacancies, but they did not fill them any faster than departments that did offer teaching time. If the new hires were recent graduates, it might make sense that the jobs with more teaching time are less desirable. New graduates may feel they need to sharpen their clinical skills before they start teaching and thus gravitate to those jobs with fewer teaching responsibilities. Lin, et al11 reported the most frequent concern among family medicine residents considering a career in academic medicine was lack of readiness to be faculty. Only 28% of departments offered protected time for research, and those departments were not able to fill a greater percentage of their positions or hire faculty any sooner.

Looking at the characteristics associated with the most recent hire, we found no association between how long the position was vacant and the FTE for teaching, research, clinical, and administrative time. We had hypothesized that the FTE would be associated with difficulty filling a position given prior findings that dissatisfaction with the balance of clinical, research, teaching, and administrative effort was associated with quitting.8 However, we did find that a higher salary and a signing bonus were associated with positions being filled more quickly. Departments that offered a signing bonus filled their positions nearly 4 months sooner than those that didn’t.

It appears that the reasons for faculty retention are different from those for faculty recruitment. High faculty turnover may not be different from rates seen in private practice. A 2015 report cites a 14% annual turnover rate for family practitioners,12 which is slightly higher than the rate found in academic family medicine.1

The reasons for leaving a job are not the same as the factors that affect filling a job. A stronger focus should be on faculty retention so there are fewer vacancies to be filled. There has been much published on retaining physicians in their current jobs. A 2017 survey revealed that 60% of physicians reported “cultural attributes” such as having skilled leadership who were attuned to physician needs and concerns as being extremely important in their desire to stay in their current job.13 Compensation models that reward clinical productivity, panel size, and quality measures have also been successful in reducing turnover rates.14

Limitations

Characteristics of the most recent physician faculty hire may not be representative of all faculty hires. However, we chose to ask about the most recent hire because it would be fresh in the chair’s mind and would be more specific than a chair’s mental average of the characteristics of all hires from the previous 12 months. Another limitation resulted from our use of the chairs’ description of FTE allocation. Allocation of physician FTE for clinical, teaching, research, and administrative time may not be an accurate representation of actual time spent or the right balance for faculty. Pollart, et al found that the actual FTE of clinical and administrative time did not predict intention to leave a job, but rather the perception that whatever the amount of time was, it was “too much.” We were unable to survey the person hired to get their perception of the balance of FTE.

To address the limitations caused by examining characteristics of the job, future studies should ask newly hired faculty themselves about the reasons they took a new job. Salary and signing bonuses may be important, but other factors such as geographic location, reputation, proximity of friends and family, or career goals may play a significant role. We’re likely to get better data by directly questioning faculty rather than inferring the importance of incentives offered by departments. Future studies should also ask new faculty about the importance of the FTE balance in their decision to take a new job. Comparing the posted FTE at the time of hire and the actual time spent teaching a year later may provide additional insight. Finally, we should describe what is meant by protected time for teaching and FTE for teaching. Participants could have interpreted teaching time as formal classroom teaching or supervising in clinic. We should clarify whether this also includes teaching while simultaneously providing clinical care to one’s own patient panel. Because teaching is an important part of an academic physician’s job, the definition needs to be clarified in future studies.

Conclusion

We did not find that offering protected time for teaching or research was associated with success in hiring new faculty. Nor did we find that FTE allocation for clinical, teaching, research, and administrative time were associated with successfully hiring new faculty. Offering higher salaries and signing bonuses were associated with hiring faculty more quickly. However, salary was not cited as a reason for leaving a position.9 Failing to retain clinical physician faculty continues to be an expensive and disruptive problem. Future studies should investigate factors that increase the likelihood of faculty remaining in their current position, which may be a more cost-effective option.15

References

- Corrice A, Fox S, Sarah B. Retention of full-time clinical MD faculty at US medical schools. AAMC Analysis in Brief. 2011;11(2):1-2.

- Phillips N. An invitation. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13:290-291.

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-576. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1713

- Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sloan JA, et al. Career fit and burnout among academic faculty. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(10):990-995. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.70

- Agana DF, Porter M, Hatch R, Rubin D, Carek P. Job satisfaction among academic family physicians. Fam Med. 2017;49(8):622-625.

- Linzer M, Poplau S, Babbott S, et al. Worklife and wellness in academic general internal medicine: results from a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(9):1004-1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3720-4

- Girod SC, Fassiotto M, Menorca R, Etzkowitz H, Wren SM. Reasons for faculty departures from an academic medical center: a survey and comparison across faculty lines. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0830-y

- Pollart SM, Novielli KD, Brubaker L, et al. Time well spent: the association between time and effort allocation and intent to leave among clinical faculty. Acad Med. 2015;90(3):365-371. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000458

- Bucklin BA, Valley M, Welch C, Tran ZV, Lowenstein SR. Predictors of early faculty attrition at one Academic Medical Center. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-27

- Mainous AG III, Seehusen D, Shokar N. CAFM Educational Research Alliance (CERA) 2011 Residency Director survey: background, methods, and respondent characteristics. Fam Med. 2012;44(10):691-693.

- Lin S, Nguyen C, Walters E, Gordon P. Residents’ perspectives on careers in academic medicine: obstacles and opportunities. Fam Med. 2018;50(3):204-211. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2018.306625

- Singleton T, Miller P. The physician employment trend: what you need to know. Fam Pract Manag. 2015;22(4):11-15.

- Cejka Search.2017 Physician and Advanced Practitioner Burnout Survey Reveals Key Drivers of Physician Wellness and Retention, 2017. https://www.cejkasearch.com/docs/wellness-survey-summary.pdf. Accessed March 11, 2019.

- Trowbridge E, Bartels CM, Koslov S, Kamnetz S, Pandhi N. Development and impact of a novel academic primary care compensation model. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12):1865-1870. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3410-7

- Stovall G, Shutte L. Investing in retention pays dividends. Group Pract J. 2011; September.

There are no comments for this article.