Entrustable professional activities (EPAs), a term derived from the competency-based education movement, refers to a list of tasks that can reliably be performed by professionals in a given discipline. A list of 20 EPAs for family medicine was approved by our discipline in 2015.1 In this issue of Family Medicine, we feature a paper by Jarrett and colleagues about the use of these EPAs in family medicine residencies.2 The authors surveyed family medicine residency directors in collaboration with the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA). Of the 267 program directors who completed the survey (53% response rate), 82% were aware of EPAs, but only 60% were confident in how to use them as an evaluation framework and only 15% were currently using them for this purpose. Perhaps this is understandable. Over the past decade, competency-based educational methods have gradually replaced experience-based models and this change has worked its way slowly into the process of resident evaluation. Proponents argue that we should assess residents by directly observing live or simulated performance rather than counting the amount of time they spend in the learning process or the number of procedures they perform. Thus, lists of competencies and milestones have replaced counts of rotations completed and procedures performed in the evaluation process.

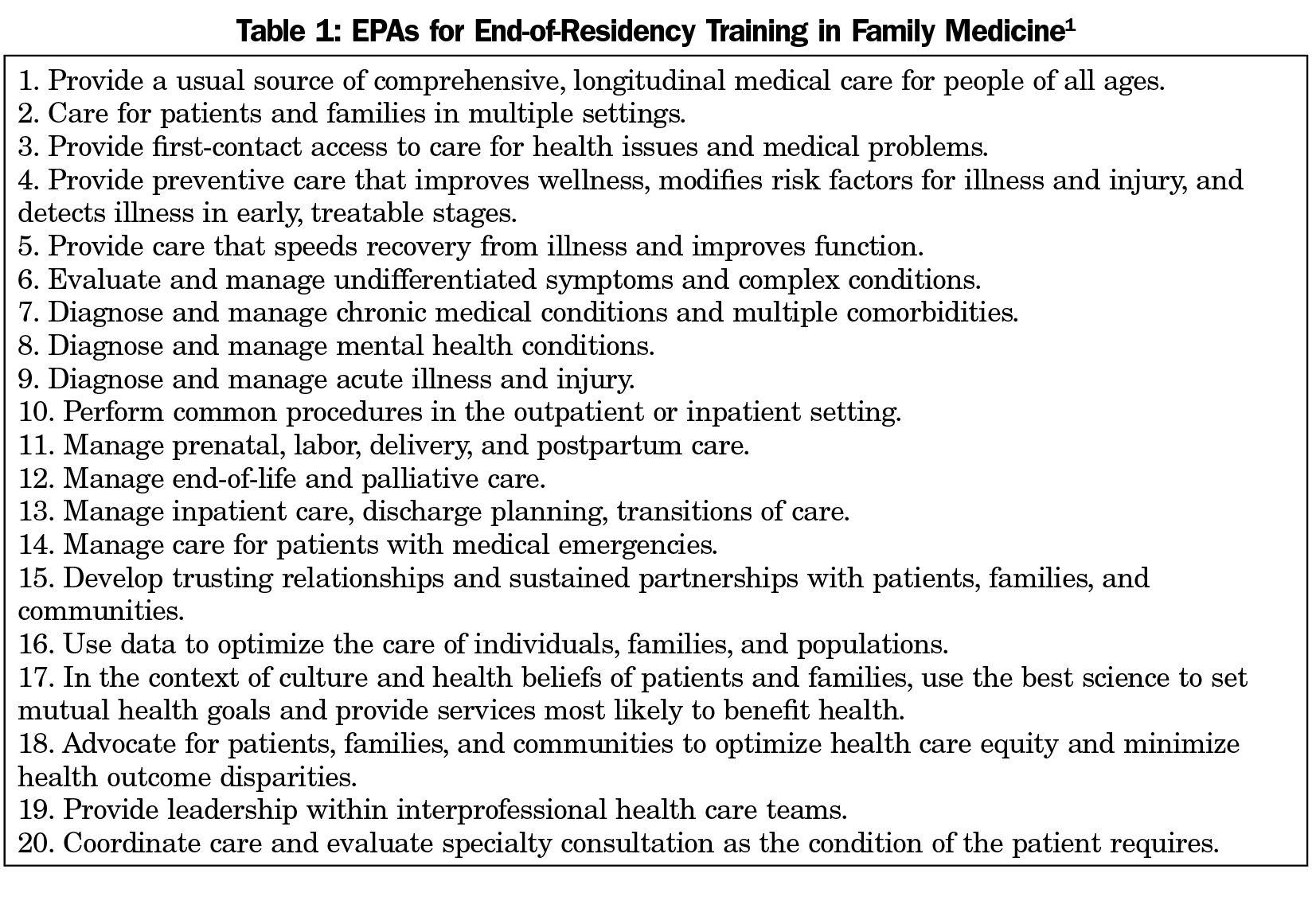

Whether or not one thinks this is a good idea, the transition has been rocky. Competency-based assessment was adopted by accrediting bodies with little evidence that they work better than traditional models. Critics have argued that the competencies and milestones are too granular and therefore fail to coherently reflect whether broad training goals are accomplished. So the notion of EPAs was devised as a way to assess these broader goals. The 20 family medicine EPAs (Table 1) were developed at the start of Family Medicine for America’s Health (FMAHealth). The goal at that time was to create a list of the skills and attributes the American people could trust a family physician to possess. Implied in this process is that our medical schools would use these EPAs as a tool to explain our discipline to medical students and that our residencies would deliver on the promise by producing graduates who could be trusted to have the skills listed therein. There was substantial debate at the time these were created. Many felt the list should apply to all family physicians, but others feared that this would disenfranchise the many physicians in practice who are not currently practicing all of the skills on the list. Therefore, the final list was intended only to state what family physicians are being trained to do, not what they actually are doing. Now, 4 years later, it seems we have no idea of whether this is happening or not.

When the first family medicine residencies opened in 1969, there was plenty of opposition. Some general practitioners were concerned that residency education for new family physicians would leave them behind. Many specialists refused to teach family medicine residents, worrying about competition in areas of practice that overlapped with their own. As our discipline celebrates its 50th birthday, we have largely overcome this opposition thanks to hard work at both the local and national levels. Today, specialists are mostly happy to have us delivering comprehensive care, particularly if we are caring for poor people in communities where they do not want to work. Family medicine is established; we have become the largest specialty in American medicine.

Now we face new sources of opposition to a comprehensive scope of practice. Our residencies are controlled to a substantial degree by their sponsoring institutions. Hospital and health plan leaders want family physicians who mostly will care for adults with chronic illnesses in the office setting and they hire program directors who will prioritize these local goals. Family physicians in rural and underserved communities need broader skills than those in urban and suburban areas, but most of our residencies are in urban areas. Thus, our commitment to comprehensive training wanes. Today, the greatest threat to our discipline’s future is our own inability to agree with one another about what it means to be a family physician. This is not a new problem; internal arguments about our scope of practice date to the earliest days of our discipline. Six years ago, FMAHealth was undertaken to formulate a renewed promise to the American people; not urban Americans or insured Americans, all Americans. So here are some questions for us to consider:

- Do we care if the American people have a coherent idea of what they can expect from a family physician?

- Should the public be able to count on any family medicine practice to deliver a basic set of services?

- Should every graduating resident be trained to perform each of the 20 activities listed in Table 1? Stated another way, should any residency graduate be able to practice as a family physician in any community?

- If we can agree on a set of EPAs as our promise to the American people, how will we hold ourselves accountable to our own promise?

When FMAHealth started, our answer to the first three of these questions was yes. That was in 2013. Are these still our answers today? If so, we are left with question number four. Organizationally, we might say that responsibility for enforcement lies with the residency accreditation process and with the American Board of Family Medicine. Certainly, the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors has a role to play in this. But, in reality, the responsibility lies with each and every one of us. One of the essential attributes of a profession is the responsibility to self-regulate its members in the public interest. If family medicine is a profession, then we have a responsibility of self-determination. If we are not a profession, we are simply employees and decisions about what we do will fall to our employers. Defining our profession is not the responsibility of hospital administrators or the leaders of corporate medicine; the responsibility lies with the profession itself and our choices should be based on the needs of those we serve. For now, family medicine remains a profession and we are responsible for all of America, not just for those fortunate enough to live in the right place. Self-determination is our duty. We can change these EPAs, but we must not make promises we do not intend to keep. If we fail the test of self-determination, we can no longer blame medical school deans and other specialties for poor student interest in family medicine; and we cannot expect the American people to know what a family physician is.

There are no comments for this article.