Background and Objectives: In Ethiopia, family medicine began in 2013. The objective of this study was to compare family medicine residents’ attitudes about training in Ethiopia with those at a program in the United States.

Methods: Family medicine residents at Addis Ababa University in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and the University of Maryland in Baltimore, Maryland completed a 43-item Likert scale survey in 2017. The survey assessed residents’ attitudes about residency education, patient care, independence as family physicians, finances, impact of residency on personal life, and women’s issues. We calculated descriptive statistics on the demographics data and analyzed survey responses using a two-sample t-test.

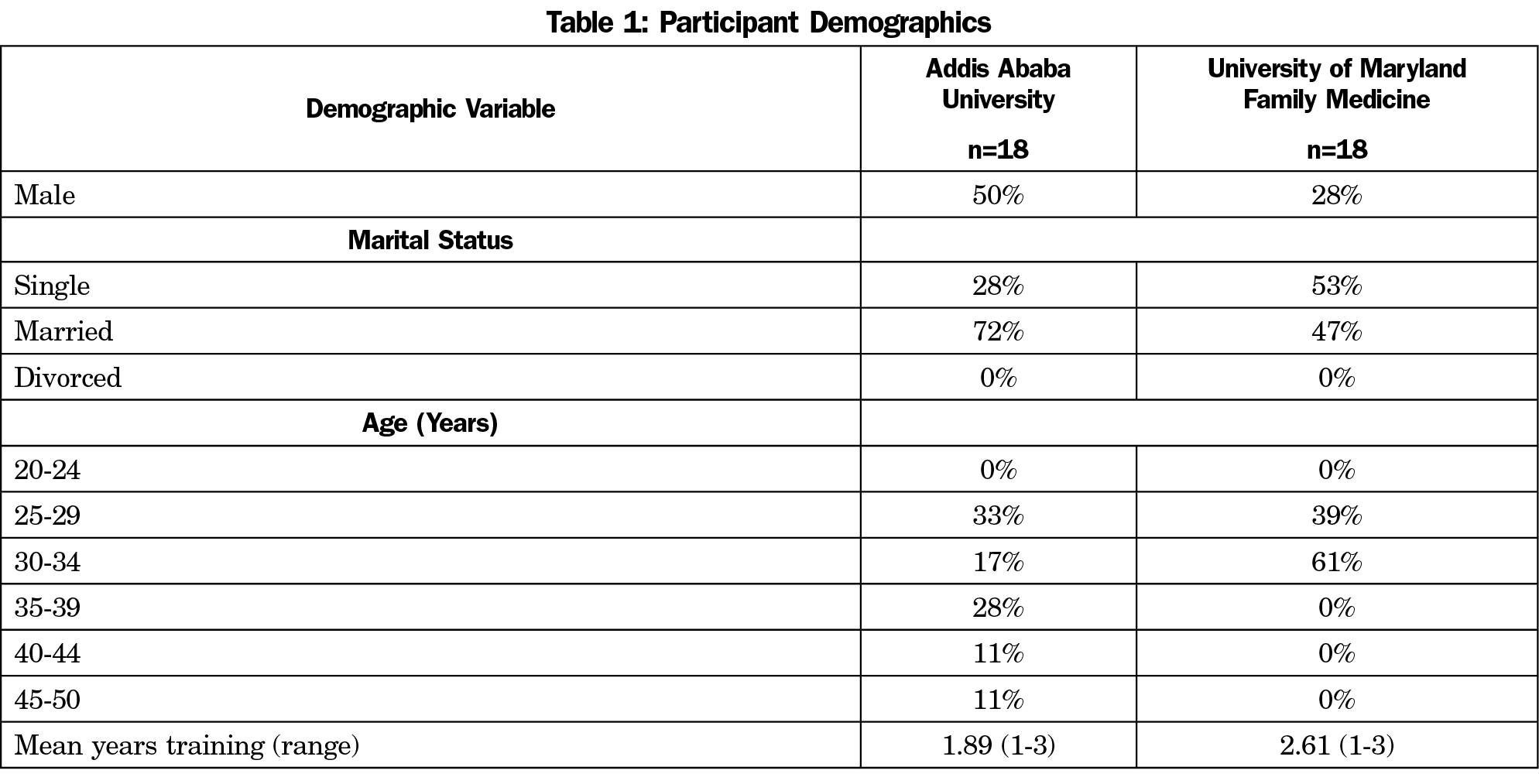

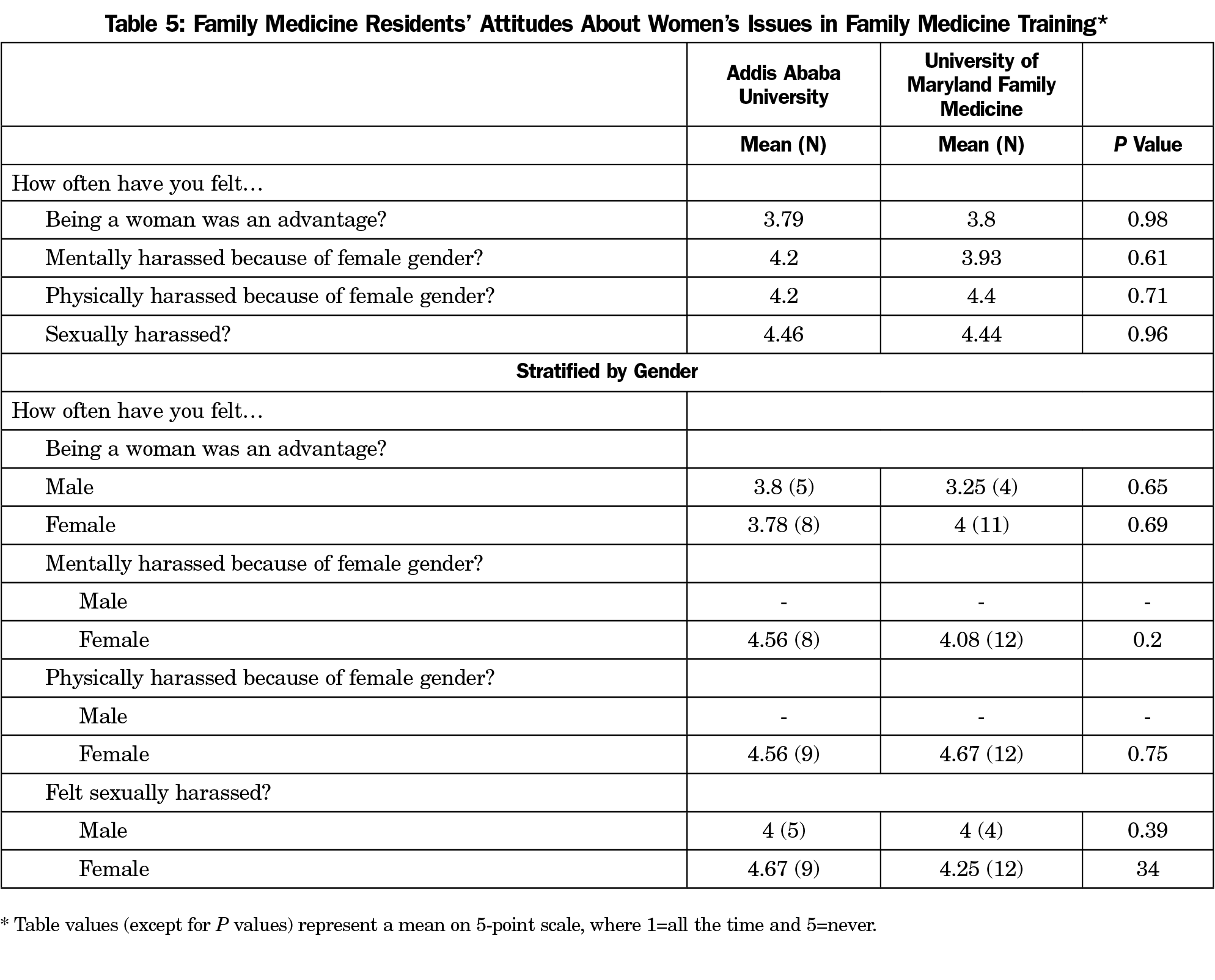

Results: A total of 18 (75%) Ethiopian residents and 18 (60%) US residents completed the survey (n=36). The Ethiopian residents had a wider age distribution (25-50 years) than the US residents (25-34 years). More US residents were female (72%) compared to the Ethiopian cohort (50%), while more Ethiopian residents were married (72%) compared to the US cohort (47%). There were statistically significant differences in attitudes toward patient care (P=0.005) and finances (P<0.001), differences approaching significance in attitudes toward residency education, and no significant differences in independence as family physicians, the impact of residency on personal life, and women’s issues in family medicine.

Conclusions: Across two very different cultures, resident attitudes about independence as family physicians, the impact of residency on personal life and women’s issues, were largely similar, while cross-national differences in attitudes were found relative to residency education, patient care, and finances.

Family medicine (FM) developed in the United States in the mid-20th century due to increasing subspecialization and a declining number of general practitioners (GPs) providing comprehensive care.1-3 A handful of family medicine-trained specialists aside, Ethiopia primarily has GPs who have completed medical school and a 1-year internship. In Ethiopia, formal FM training began in 2013 with the intent to strengthen the primary care workforce.4,5

While prior research shows that residency training is stressful,6-9 little research exists about FM training in Ethiopia.4,5,10 Resident perspectives can be valuable for evaluating and developing curriculum. As such, we assessed Ethiopian and US FM residents’ attitudes about their training to elucidate aspects of FM that are similar across cultures and those that are culture-specific to guide curriculum development. We utilized research procedures followed by Fetters et al from 1991 and 1995 that compared FM residents’ attitudes about their training in Japan and the United States.11

We hypothesized that the stress of residency training would be similar across the two cultures. Given FM is well established in the United States, we expected that US residents would feel more satisfied with their residency education, independence as family physicians (FPs), and patient care. We anticipated that Ethiopian residents would feel more financial burden given Ethiopia is a low-income country, and more women’s issues based on previous reports.12,13

This was a cross-sectional study using a 43-item survey including demographics items and 5-point Likert scale questions (1=all the time, 2=frequently, 3=sometimes, 4=infrequently, 5=never).11

We administered the survey in 2017 at Addis Ababa University, the only FM training program in Ethiopia, and at the University of Maryland in the United States. The program at Addis Ababa University is 3 years long and is based in a 700-bed university hospital with seven residents in each class— about 50% female—and five faculty. The program at the University of Maryland is also 3 years long and based in a 757-bed university hospital and one family practice center with 10 residents per class—about 70% female and 50% underrepresented minorities—and 15 faculty. The majority of the residents are from allopathic medical schools across the United States with one to two international medical graduates per class.

We calculated descriptive statistics on the demographics data and compared the responses from the two groups with a two-sample t-test using statistical software R. We considered P values below 0.05 as statistically significant. The University of Maryland and Addis Ababa University Institutional Review Boards both exempted this study.

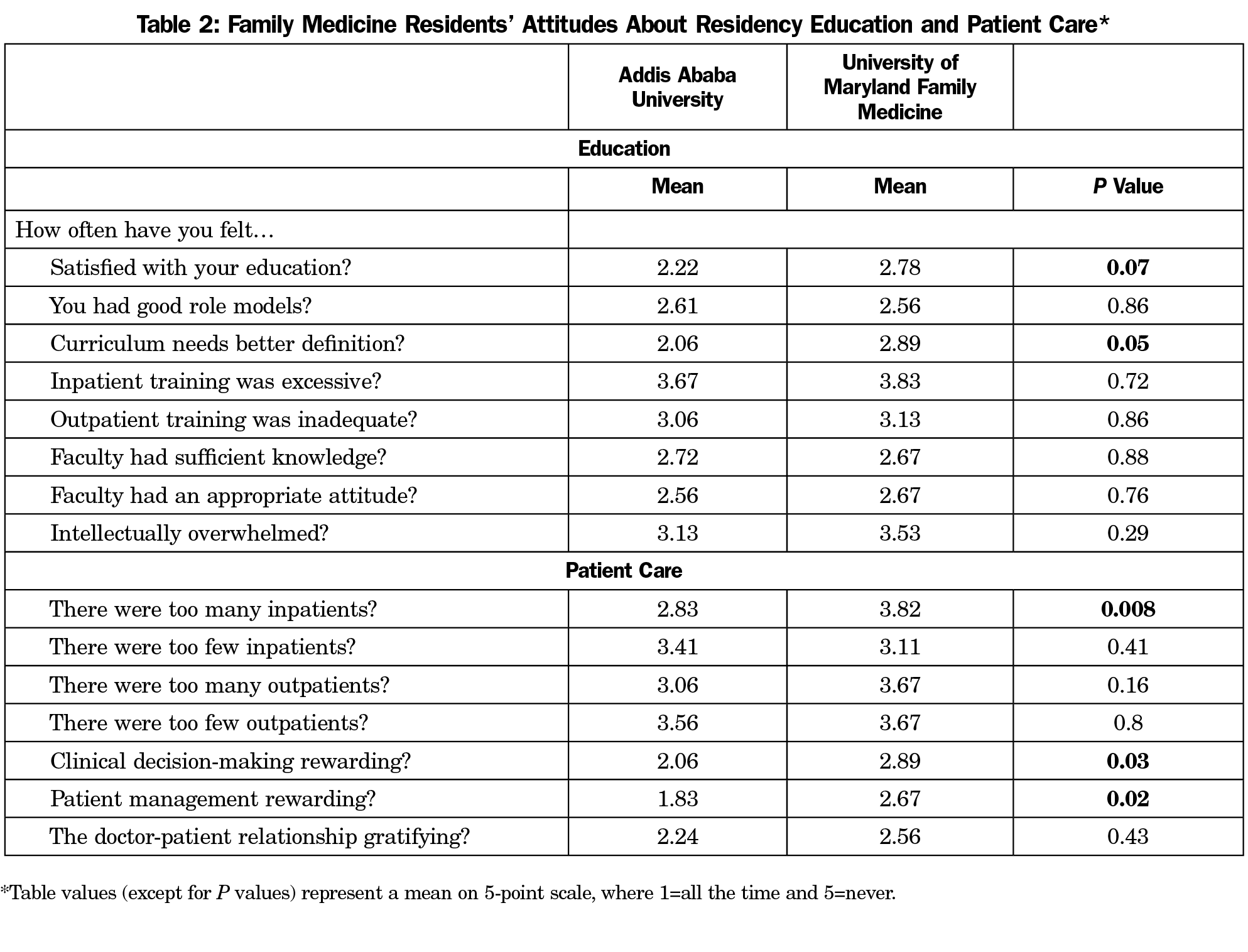

The participants’ demographics data are listed in Table 1. The response rates were 60% (18/30) for the United States and 75% (18/24) for Ethiopia. Although the differences in views about residency education between the two groups overall were not significant, higher reports by Ethiopian residents of feeling more frequently satisfied with their residency education (P=0.07), and that the curriculum needed better definition (P=0.05) approached significance (Table 2).

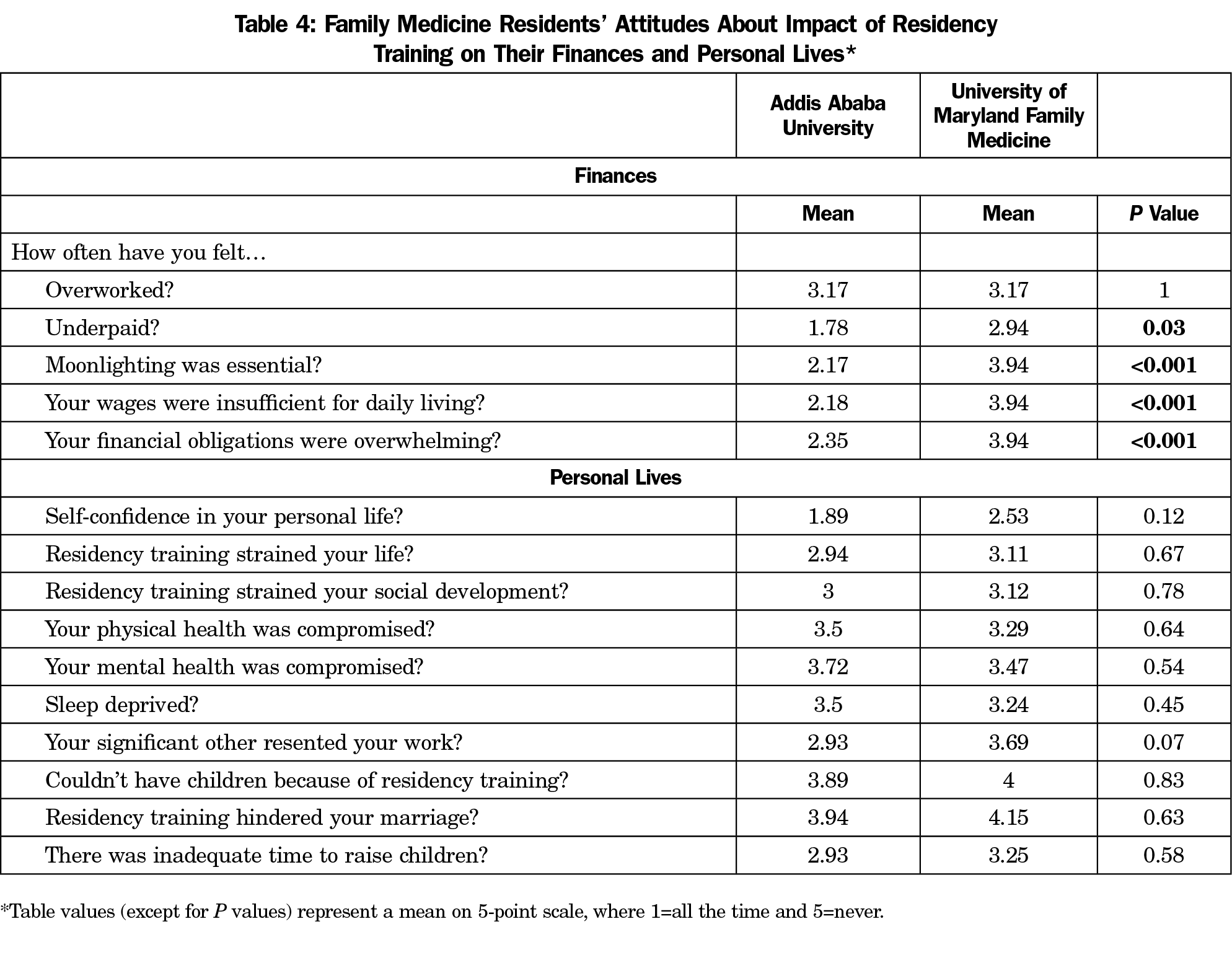

The Ethiopian residents reported having too many inpatients (P=0.008), however, they rated clinical decision-making (P=0.03) and patient management (P=0.02) more rewarding than the US residents (Table 2). The Ethiopian residents also reported feeling more underpaid (P=0.03), that moonlighting is essential (P<0.001), wages are insufficient for daily living (P<0.001) and their obligations are overwhelming (P<0.001; Table 4).

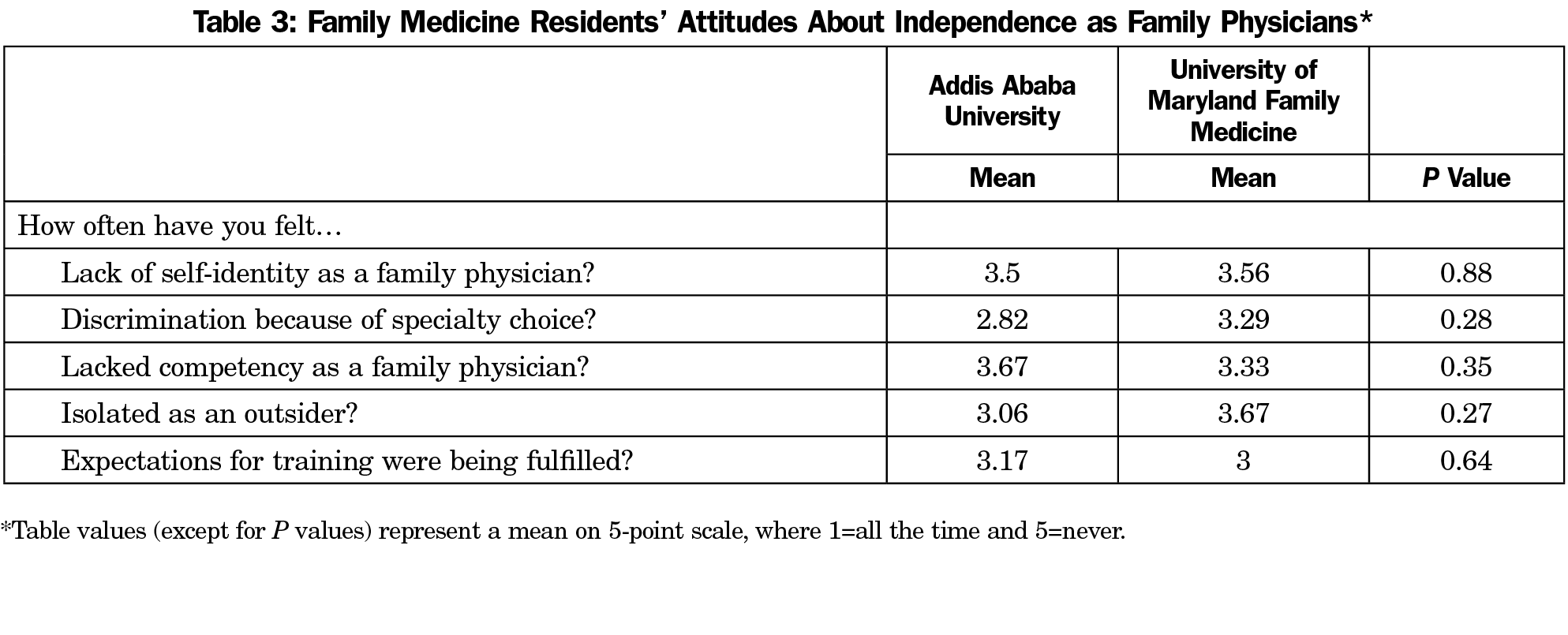

There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups regarding independence as FPs (Table 3), impact of residency on personal life (Table 4), and women’s issues in FM training (Table 5).

While the difference only approached statistical significance, the Ethiopian residents reported that their curriculum needs better definition. This is as expected given the program is new and the curriculum is evolving. The Ethiopian FM curriculum will benefit from further definition as the scope of FM practice in Ethiopia becomes further defined. The Ethiopian residents also reported feeling satisfied with their residency education at a higher level that approached significance. This may reflect changes occurring in the US program at the time of the survey.

The Ethiopian residents reported excessive inpatient volume. This is as expected given the majority of their training is hospital-based, and a dedicated FM outpatient training center is lacking. Although both programs in this study are based in tertiary hospitals, hospitals in Ethiopia have larger patient volume. As important context, physician density in Ethiopia is 0.03 per 1,000 population compared to the World Health Organization recommended 2.3 physicians per 1,000 population.14,15 In addition, hospital-based care is common in Ethiopia due to an underdeveloped health system.

Contrary to our expectations, the Ethiopian residents found clinical decision-making and patient management more rewarding than the US participants, which may be attributable to excitement about the new specialty of FM and a novel approach to patient care. Additionally, the Ethiopian residents may have more autonomy in patient care given the physician shortfall. The US residents’ responses may reflect the current climate with reports of high burnout among medical students and residents.7,16 Our findings add to the growing awareness of physician burnout in the United States.

We anticipated that the US residents would feel more independence as FPs, but we found no significant differences between the two groups. This supports earlier findings by Fetters et al11 and a 2013 survey of US medical students who chose a primary care specialty—many reporting experiences of negative talk about primary care from other specialists at their medical schools.17 This highlights the continued struggle for FM to gain full acceptance in the United States.

As expected, the Ethiopian residents reported more financial hardship than their US counterparts. The median US medical student debt is $195,000 upon graduation.18 While education is free in Ethiopian, there is a 2-year service mandate after medical school. Additionally, the Ethiopian residents likely have more financial obligations given most of them have worked as GPs before residency and have families. Moonlighting is common in Ethiopia, but the demands of residency may be limiting. Though FM is among the least compensated specialties in the United States,19 the earning potential for US FPs is significantly higher than in Ethiopia where FM roles are still evolving and limited FM career opportunities exist. Clarifying FP roles and fostering FM career opportunities are needed in Ethiopia.4,5

As anticipated, both groups equally felt the impact of residency on personal life. This confirms findings by Fetters et al,11 and suggests that many aspects of FM residency are inherently challenging, transcend culture, time, and socioeconomic context. A long-term commitment and continued attention are needed to address and minimize challenges of FM training that occur regardless of culture or socioeconomic standing.

While we expected that the Ethiopian residents would report more women’s issues, no significant differences were seen between the two groups, even after stratifying by gender. Gender-based concerns have not been studied at the postgraduate level in Ethiopia, however, gender inequality and gender-based violence have been reported at the undergraduate level.12,13 The small sample of female participants in our study may have felt uncomfortable reporting harassment. The US findings are similar to findings of Fetters et al,11 though high rates of harassment in medical school and residency have been previously reported.20 Our survey questions may have been too general to detect different forms of harassment that residents experience. Additional research may be needed to examine gender-based harassment during FM residency.

This study has limitations. More statistically significant differences may have been detected with a larger sample size. The study was conducted at a single US site, which may limit generalizability. Still, the findings fairly represent the opinions of University of Maryland residents who train in a US family medicine residency program.

There are no comments for this article.