Background and Objectives: As part of a national pilot, the Lehigh Valley Family Medicine Residency Program implemented curricular changes to emphasize family medicine identity. These changes included limiting first-year inpatient experiences, adding “interval” outpatient weeks, and increasing family physician mentorship. This study explores how postgraduate learners describe their professional identities within the context of their chosen specialty, as defined by Family Medicine for America’s Health (FMAHealth).

Methods: This qualitative study approached family medicine identity formation from a social constructionist framework using evolved grounded theory. We performed a thematic analysis of focus groups conducted over 12 years with first-year residents (n=73). Then, utilizing a matrix analysis, articulations about professional identity were compared with structural components of the FMAHealth definition of the specialty. Three cohort groups (Preimplementation, Implementation, and Postimplementation) were defined to conduct a longitudinal comparison.

Results: Six unique biosketches synthesizing the analyses emerged. Expansion in ability to articulate professional identity was evident not only across, but also within cohort groups. The Preimplementation cohort entered and left their first year identifying as relationship-centered generalists desiring guidance from role models. The Implementation learners used more FMAHealth language to describe their practice, later recognizing the potential it held for patient care. Similarly, the Postimplementation cohort entered with a broader view of family medicine and exited wondering how to help advance its reach.

Conclusions: Curricular changes placing interns within specialty-relevant learning settings coincide with thematic differences in articulations in professional identity. These findings suggest that experiential learning and role modeling contribute to professional identity formation among graduate medical learners.

Like their colleagues entering other medical specialties, family medicine interns will spend time during residency establishing a professional identity within their chosen field. What first-year residents are able to articulate about themselves in these new roles emerges from explicit influences (eg, personal experiences and academic lessons) as well as implicit guideposts (eg, the hidden curriculum of medical education1,2 or organizational culture). Interactions with peers, faculty, and professionals within family medicine as well as those in other specialties “create, maintain, and reproduce” ideas about professional identity.3

While extensive theoretical literature exists on identity formation,4-9 the majority of the research about medical professional identity focuses on undergraduate transitions10 or development of clinical competency skills.11,12 We seek to better understand the stages through which family medicine residents progress toward “thinking, acting, and feeling like a physician.”13 A set of quantitative constructs exists for measuring family medicine identity,14 and this qualitative study seeks to utilize a nationally accepted definition of the specialty to operationalize a qualitative means of describing how family medicine residents articulate professional identity.

Redefining Family Medicine Education

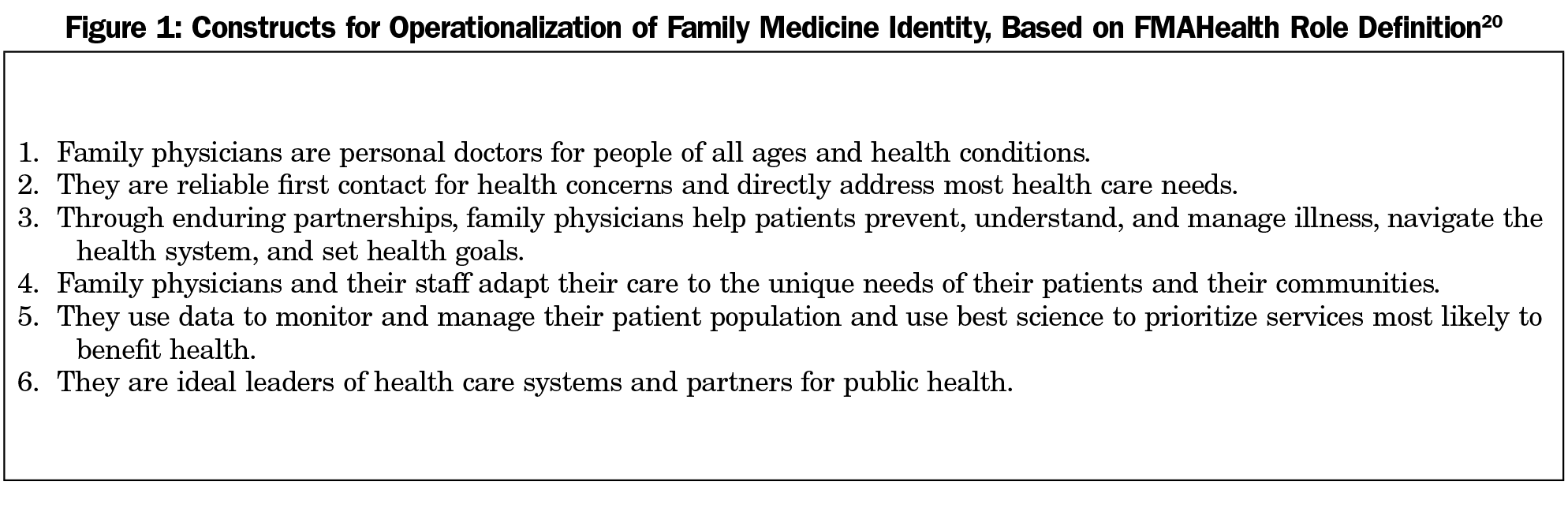

Sixteen years ago at the Keystone III conference, a core group of family medicine organizations collaborated to develop “a strategy to transform and renew the specialty of family practice to meet the needs of people and society in a changing environment.”15 Educational changes such as the Preparing the Personal Physician for Practice (P4) national demonstration project16,17 were a part of the Future of Family Medicine (FFM) 1.0 project’s restructuring plan. The P4 project challenged residency programs “to create a new context for education”18 that would better prepare family medicine graduates to deliver the model of care envisioned at Keystone III. In 2013, the FFM consortium members reconvened to provide a clearer definition of the role of family physicians in the 21st century. Considering the triple aim,19 the FMAHealth project intended to set family medicine’s identity development20 back on course (Figure 1).

Residency Innovations

In the fall of 2007, as one of the 14 P4 pilot sites, the Lehigh Valley Family Medicine Residency Program (hereafter referred to as “the residency”)—a large, multicampus, tertiary care health network in southeastern Pennsylvania—began its 5-year educational redesign. The curricular changes increased mentorship time with family physician role models, placing greater emphasis on outpatient care. The revised first-year inpatient curriculum was limited to first-contact care specialty rotations, including family medicine service, emergency medicine, pediatrics, and newborn nursery/labor and delivery. Inpatient rotations in other specialties (eg, intensive care unit [ICU]) were moved into the second and third years of residency. First-year schedules were restructured to feature interval training, which alternates inpatient weeks with outpatient weeks to encourage earlier establishment of continuity relationships in their family practice sites.

Research Objective

This retrospective qualitative research study is designed to explore how new family medicine practitioners understand what it means to be members of this specialty. We performed a secondary analysis of first-year resident focus groups to explore changes in articulations of family medicine professional identity. Our network’s Institutional Review Board granted approval for this study, certifying that it met the federal requirements for exemption as per 45 CFR 46.101(b).

Approaching the topic from a social constructionist theoretical framework,21 this study considers how first-year residents described their membership within the family medicine discipline and how this changed after embedding themselves within a specialty-focused graduate medical education program. Evolved grounded theory22 was used to perform a thematic analysis23 of focus group transcripts collected before, during, and after the implementation of curricular changes designed to emphasize family medicine practice.

Data Collection

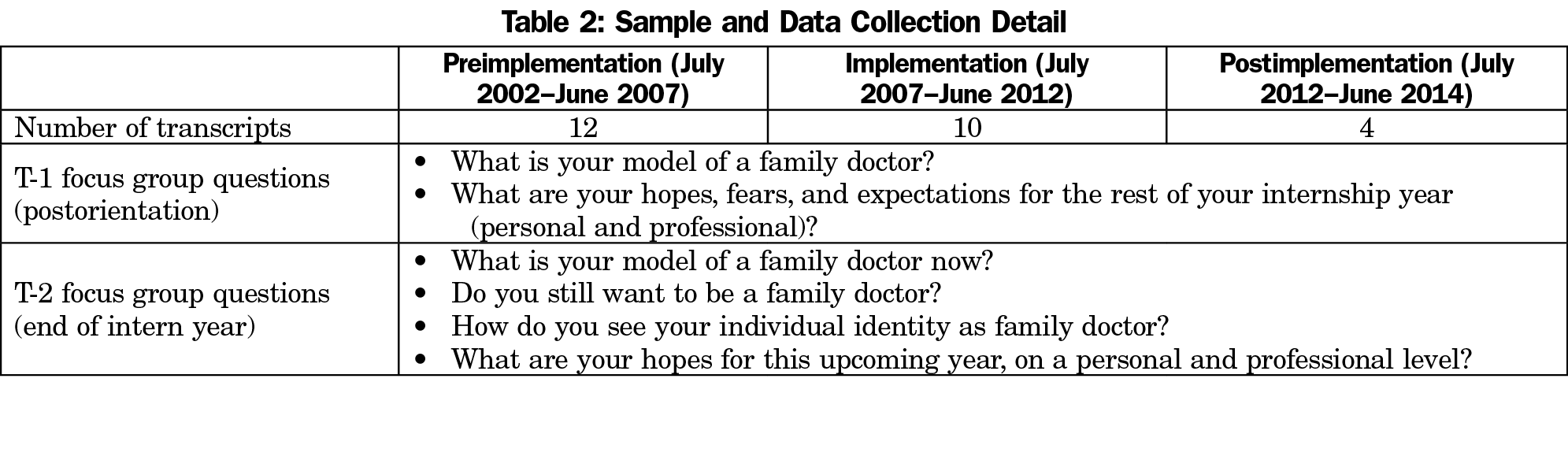

The dually-accredited residency houses a traditional 6-6-6 cohort structure. As part of the residency’s program evaluation process, each cohort participates in annual focus groups, which are audio recorded and then transcribed. The first-year class participates in two focus groups—one immediately after the orientation period (T-1) to capture baseline perceptions and feedback on these initial activities before they are conflated with other first-year experiences, and the other at the end of the academic year (T-2). The standardized question set includes specific questions about professional identity (Table 2). This study examines transcripts of focus groups conducted with first-year residents between July 2002 and June 2014.

Sample

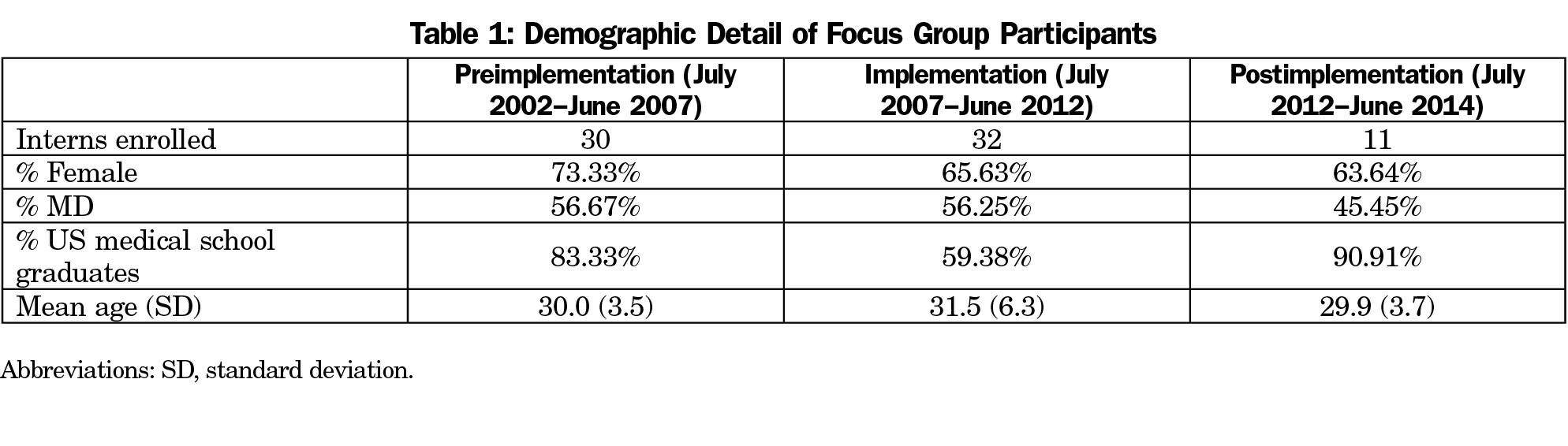

The deidentified data set represents the 73 individuals enrolled as first-year residents during the study period (Table 1). The 26 focus group transcripts were divided into three cohort groups—Preimplementation (July 2002-June 2007), Implementation (July 2007-June 2012), and Postimplementation (July 2012-July 2014)—with Implementation representing the period the residency participated in the P4 national demonstration project.16,17 The cohort groups were subdivided into T-1 (postorientation) and T-2 (end of intern year), for a total of six cohort subsets (Table 2).

Role of Researchers

The research team members have various roles within the residency: two (S.M., J.D.) are family medicine physician faculty, and two (S.H., N.B.) are interprofessional faculty members who lead the residency’s program evaluation efforts, which includes facilitation of resident cohort focus groups. The fourth author (J.D.) also served as residency program director for the majority of the time period covered by this study, and was thus recused from primary data analysis, instead serving in a member-checking role. This is one of several study design considerations made to reduce bias and ensure quality of research. The research team includes individuals who were part of the original P4 evaluation design team (N.B., J.D.) as well as those who were not (S.H., S.M.).

Analysis

Analysis of the data set occurred in several stages.24 The process began with verbatim transcription of all focus groups conducted between July 2002 and June 2014. Using NVivo 10 software (QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia). A seven-member data analysis team (S.H., N.B., S.M., and four others named in the Acknowledgments section of this paper) coded the complete transcripts using an a priori coding scheme representing the residency P4 project’s five overarching areas of inquiry: (1) Adult Learning, (2) Relationship-Centered Clinical Practice, (3) Family Medicine Identity, (4) Satisfaction With Life, and (5) General Program Feedback. The sections coded to the Family Medicine Identity node were extracted for secondary analysis.

Three authors (S.H., S.M., N.B.) independently reviewed the coded transcripts, separated into six cohort subsets (Table 2), to identify emergent themes. The group reconvened to compare thematic findings and, by consensus, to identify exemplar quotes. This was an iterative process; each cohort subset was revisited to ensure saturation. The final themes for each cohort subset were sent to the last author (J.D.) for member checking from a programmatic perspective.

The third stage of data analysis involved the creation of a matrix utilizing the six components of the FMAHealth definition20 (Figure 1) as constructs to operationalize family medicine identity. The emergent themes and companion quotations extracted from the focus group transcripts were matched to related components of the FMAHealth definition.

To capture the unique family medicine identities that emerged for each cohort group at T-1 and T-2, the authors synthesized the matrix analysis described above into six biographical sketches (Table 3) highlighting the most pervasive themes. The articulations illustrate some notable differences between the cohorts, which are outlined below.

- FFM Construct 1—“Personal Doctors”: While all three cohort groups at T-1 noted care across the lifespan, each cohort emphasized a different aspect of this role. Preimplementation speakers focused on the personal relationships formed with families: “The family doctor is … a patient’s friend, confidante, and healer rolled up in one” (T-1, July 2003); and “They are totally mixed with the family at the basic level” (T-1, August 2002). The Implementation cohort members spoke more pragmatically, pointing to the family physician as a “generalist, who meets their patients at their point of need” (T-1, September 2011) who is “taking into consideration that whole person ... all aspects of their health, mental, physical, social, um, spiritual” (T-1, September 2009). The Postimplementation cohort exhibited self-awareness as the foundation for patient care: “I think just acknowledging your own emotions and how it plays a role … how you practice and how you are as a physician” (T-1, October 2012).

- FFM Construct 2—“First Contact”: All three cohorts at T-1 referenced this aspect of family medicine practice, focusing on a need for “broader-based knowledge” (Postimplementation, T-1, October 2012) to provide first-contact care: “We are the initial caregivers. And we assess at that time” (Implementation, T-1, August 2007), to “a wide variety of patients” (Preimplementation, T-1, July 2003).

However, at T-2, differences between the cohorts were apparent. The Preimplementation cohort saw their strengths as having the “interpersonal skills” (Preimplementation, T-2, June 2005) to “talk to a family in a better manner than the other department doctors” (Preimplementation, T-2, June 2004). The Implementation cohort embraced their growing adaptability and competencies: “You’re comfortable with kids. You’re comfortable with cultural issues … comfortable with working in the community … with different hospital staff” (T-2, June 2008). The Postimplementation cohort noted how family medicine “front-line care” fills gaps in the health care system: “At times it feels a family doctor, uh, can be a cardiologist to the patients that can’t quite afford or can’t get in with the cardiologist, or psychologist, or neurologist. You know, we’re the safety net of the medical community” (T-2, May 2013). - FFM Construct 3—“Enduring Partnerships”: The Preimplementation cohort referred to continuity as “long-forming relationships” (T-1, July 2004) for multiple members of a single family. “You could draw a connecting line from each one of them to a single-family practitioner and, with that, comes a lot of insight and opportunity to not only treat while ill but treat while healthy” (T-1, July 2003). The Implementation and Postimplementation cohorts agreed, and added that at the bounds of their knowledge: “We’re not expected to know the huge in-depth portions of all those different subjects” (Implementation, T-1, August 2007), was the option to enlist “help from specialists” (Postimplementation, T-1, September 2013).

However, at T-2, the cohorts diverged on this construct. Preimplementation learners described hits to their “self-worth and … worth in the whole medical field” (T-1, June 2004), based on perceived lack of respect from inpatient colleagues in other specialties. While the Implementation cohort noted similar concerns about the reputation of family medicine: “I don’t think we’re well respected as we should be” (T-2, June 2008), this didn’t dissuade them from seeking more continuity with patients. - FFM Construct 6—“Leaders/Partners”: The cohorts perceived the idea of family physician leadership in vastly different ways. The Preimplementation cohort saw family physicians as “well respected … community leaders” (T-1, July 2004). The Implementation learners were focused on how their generation might be responsible for reclaiming respect for the specialty (“Family medicine … we are the leaders. … I think, um, we may not have been in that position the last several years, but it’s time” (T-1, September 2010); and “I see it as, again, the gatekeeper of healthcare. And, um, the medical home … We’re kind of like the forerunners in that also” (T-2, April 2011). The Postimplementation cohort pondered the shifting health care landscape more generally: “With the way that health care goes now, my views are kind of changing, and I can see the positives of patient-centered medical home” (T-1, September 2013), and the more immediate demands on them as rising senior residents: “I would like to be a, a good role model for the next class” (T-2, 2014).

A few themes outside of the FMAHealth definition20 emerged. They are noted below as evidence of the varied voices and stages of identity development:

- Flexibility in Schedule: Some respondents stated that they appreciated the choices that their specialty offered in terms of when and where they could practice family medicine. “You can be, you know, part time, full time, see patients in the hospital or just strictly outpatient…” (Preimplementation, T-1, September 2006).

- Role Clarification: At the end of the internship year, the Preimplementation cohort members expressed a need for family medicine role models: “This year really hadn’t afforded me the opportunity to be just a family doctor. I had to be the internist, the OB, um, be the pediatrician” (T-2, June 2007). By contrast, the Implementation period cohorts had begun to embrace their role as family physicians: “I was afraid to be addressed as ‘doctor’ for probably the first half of my intern year … but now I’m like, I’m owning it” (T-2, April 2007); and “[I want] to know what it is that my niche is inside family medicine” (T-2, June 2010).

- Relevance of Curricular Elements: Preimplementation learners questioned the value of some inpatient specialty rotations: “I would say for me OB is entirely irrelevant … Surgery also isn’t particularly relevant” (T-2, June/September 2006). Implementation learners made connections between inpatient rotations and outpatient work: “After the last two weeks of hospital service I found that coming back to the office, I started seeing my complex chronic patients and noticing more certain symptoms that were presenting repeatedly in the hospital and being able to help them much better” (T-2, June 2009).

Differences occurred between T-1 and T-2 in each cohort, indicating expanding ability to articulate family medicine identity over time, as would be expected from added exposure to family medicine as a discipline. In addition, we noted more frequent and more complex conceptualizations of identity within the Implementation and Postimplementation groups. The Implementation and Postimplementation cohorts articulated many more of the components of the FMAHealth definition, undoubtedly influenced by exposure to similar concepts in the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) teachings that had emerged in undergraduate medical education.

The Preimplementation cohort entered with a desire to be relationship-centered clinicians, and by the end of the first year of training found themselves with a clearer picture of what clinical competency entails, but without strong guideposts for how to translate their newfound medical knowledge into the practice of family medicine. The Implementation cohort shifted from viewing themselves as solely front-line generalists to gatekeepers for health care who recognize the PCMH model of care’s potential to serve their complex patient panels. The already self-aware Postimplementation cohort saw themselves as family physician leaders who enable continuity of care by coordinating care for patients who seek interventions from a variety of settings. Our opinion is that these shifts were influenced by the experiences the residents had during their first year of family medicine training.

This study revealed a disconnect felt by first-year residents from the family medicine specialty in the Preimplementation years. Part of the decision to join the P4 demonstration project16 was to ensure that residents were exposed to family medicine role models by moving away from the traditional rotational internship schedule. The richness of the resident cohorts’ articulations about being family physicians expanded during the time period of the curricular changes.

The impact of exposing residents to family medicine role models earlier in their training is supported in the literature. A meta-analysis of 73 studies of undergraduate medical students found that early experience in medical settings

could teach them about clinicians’ roles, responsibilities and position in society; about public health and how the health care system can improve it; and about the impact of disease on patients.10

Family medicine identity development was studied by Senf et al,25 who found that added exposure of medical students to family medicine physicians increased understanding and positive perceptions of the specialty. Moreover, our restructuring of schedules, placing residents in learning environments emphasizing primary care practice with family medicine role models, follows Swanwick’s26 assertion that informal learning occurs most effectively through “situations, not subjects.” In other words, doing the work of family physicians is more likely to influence professional identity than talking, reading, or listening to lectures about it. This embraces the concept that learning is a sociocultural process of “becoming”27,28 that transcends cognitive acquisition of skills and knowledge through participation in the “developmental space” that results from the workplace culture, personal and professional interactions, and emotional engagement of the learner.29 Monrouxe30 emphasizes the role curriculum plays in professional identity formation:

identity and identification issues affect medical education in terms of students’ relationships with patients, with doctors and with themselves and thus are of central importance to the conception and development of medical curricula. . . . Medical education is as much about learning to talk and act like a doctor as it is about learning the content of the medical curriculum.

We contend that this phenomenon occurred within the resident cohorts (Implementation and Postimplementation) who were exposed to the curricular changes that placed first-year residents in family medicine mentorship relationships, thus expanding their identification with the specialty.

Limitations

The primary limitation is that the Postimplementation cohort contained only two classes of residents, as compared with five in each of the other groupings, so identified themes might be an overrepresentation of individual experiences. Another limitation pertains to the nature of focus groups as a data collection method, in that there is no guarantee all perspectives are heard, because participants may choose not to respond to any or all questions. Also of note is that the questions asked in the focus groups were not contrived with this specific study in mind; therefore, some of the key components of the FMAHealth identity definition20 might be underrepresented in resident responses.

While the timing of the focus groups data collection allowed us to examine articulations about family medicine identity over the same time period as our curricular innovations were implemented, there is no way to fully attribute the differences between the results to curricular changes alone. We acknowledge that in any social science study, cause-and-effect claims are unreasonable. Finally, as a result of academic innovations during P4,31 the residency’s recruiting message changed to highlight our P4 participation as well as our curricular focus on adult learning, integrated care, and PCMH principals. The residency saw an increase in applicants during our period of innovation, a phenomenon experienced by other P4 sites.32 Therefore, both the Implementation and Postimplementation cohorts may have contained individuals with a broader sense of the FMAHealth concepts than the Preimplementation cohort.

Implications

We concur with the observations of Miller and Dostal33 that immersing residents in other specialty inpatient rotations during the formative first year stunts the development of family medicine professional identity of those new to the field:

This structure also promotes a reductionist framework of thinking that is problematic in the primary care setting, where whole person, community, and population frameworks are essential.33

Family medicine doctors will need to clarify for themselves and their patients which roles they perform in the ever-expanding health care diaspora.34 FMAHealth offers a holistic definition to remind family physicians of their identity amid the trends of fragmentation of care, increase in specialization, more narrowly defined scope of practice, and gatekeeper roles in managing increasingly complex patient panels.

Expansion in ability to articulate professional identification as a family medicine physician was evident not only longitudinally, but also within cohort groups from the beginning to the end of the first year of training, albeit to differing degrees. Gaining access to strong role models in the first year of residency through curricular innovations such as those described here gives learners more opportunities to become socialized into their chosen profession through the informal learning of the everyday routine35 of practicing alongside family physicians.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nicole Defenbaugh, PhD, Linda Contillo Garufi, MD, MEd, Nancy Gratz, MPA, PCMH-CCE, and Staci Morrissey, BS, for their assistance with data analysis, and William Miller, MD, and Jacqueline Grove for their insights and editorial assistance. The authors also express appreciation to the faculty, residents, and graduates of the residency program for engaging in the work of transforming medical education.

Financial Support: The Dorothy Rider Pool Health Care Trust provided funding support for this study.

References

- Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 1998;73(4):403-407. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199804000-00013

- Haidet P, Stein HF. The role of the student-teacher relationship in the formation of physicians. The hidden curriculum as process. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(S1)(suppl 1):S16-S20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00304.x

- Apker J, Eggly S. Communicating professional identity in medical socialization: considering the ideological discourse of morning report. Qual Health Res. 2004;14(3):411-429. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732303260577

- Erikson EH. Identity and the Life Cycle. New York, NY: International Universities Press; 1959.

- Chickering AW. Education and Identity. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1969.

- Chickering AW, Reisser L. Education and Identity. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1993.

- Merton RK. Some preliminaries to a sociology of medical education. In: Merton RK, Reader LG, Kendall PL, eds. The Student Physician: Introductory Studies in the Sociology of Medical Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1957:3-79. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674366831.c2

- Grose NP, Goodrich TJ, Czyzewski D. The development of professional identity in the family practice resident. J Med Educ. 1983;58(6):489-491. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-198306000-00010

- Stein HF. Family medicine’s identity: being generalists in a specialist culture? Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(5):455-459. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.556

- Dornan T, Littlewood S, Margolis SA, Scherpbier A, Spencer J, Ypinazar V. How can experience in clinical and community settings contribute to early medical education? A BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2006;28(1):3-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590500410971

- Hesketh EA, Allan MS, Harden RM, Macpherson SG. New doctors’ perceptions of their educational development during their first year of postgraduate training. Med Teach. 2003;25(1):67-76. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159021000061459

- Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt DD, Regehr G. Competency is not enough: integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1185-1190. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182604968

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1446-1451. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427

- Carney PA, Waller E, Eiff MP, et al. Measuring family physician identity: the development of a new instrument. Fam Med. 2013;45(10):708-718.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Future of Family Medicine Project 1.0. http://www.aafp.org/about/initiatives/future-family-medicine/ffm.html. Accessed March 22, 2018.

- Green LA, Jones SM, Fetter G Jr, Pugno PA. Preparing the personal physician for practice: changing family medicine residency training to enable new model practice. Acad Med. 2007;82(12):1220-1227. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318159d070

- Saultz J. Lessons from the p4 project. Fam Med. 2018;50(7):497-498. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2018.959938

- Scherger JE. Preparing the personal physician for practice (P(4)): essential skills for new family physicians and how residency programs may provide them. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(4):348-355. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2007.04.070059

- Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759-769. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759

- Phillips RL Jr, Brundgardt S, Lesko SE, et al. The future role of the family physician in the United States: a rigorous exercise in definition. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(3):250-255. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1651

- Patton MQ. Variety in qualitative inquiry: theoretical orientations. In: Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2002:96-104.

- Mills J, Bonner A, Francis K. The development of constructivist grounded theory. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):25-35. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500103

- Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398-405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048

- Cypress BS. Rigor or reliability and validity in qualitative research: perspectives, strategies, reconceptualization, and recommendations. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2017;36(4):253-263. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0000000000000253

- Senf JH, Campos-Outcalt D, Kutob R. Factors related to the choice of family medicine: a reassessment and literature review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16(6):502-512. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.16.6.502

- Swanwick T. Informal learning in postgraduate medical education: from cognitivism to ‘culturism’. Med Educ. 2005;39(8):859-865. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02224.x

- Kilbertus F, Ajjawi R, Archibald DB. “You’re Not Trying to Save Somebody From Death”: Learning as “Becoming” in Palliative Care. Acad Med. 2018;93(6):929-936.

- Hager P, Hodkinson P. Becoming as an appropriate metaphor for understanding professional learning. In: Scanlon L, ed. Becoming” a Professional: An Interdisciplinary Analysis of Professional Learning. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer; 2011:33-56. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1378-9_2

- van der Zwet J, Zwietering PJ, Teunissen PW, van der Vleuten CP, Scherpbier AJ. Workplace learning from a socio-cultural perspective: creating developmental space during the general practice clerkship. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2011;16(3):359-373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9268-x

- Monrouxe LV. Identity, identification and medical education: why should we care? Med Educ. 2010;44(1):40-49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03440.x

- Carney PA, Eiff MP, Green LA, et al. Preparing the personal physician for practice (P⁴): site-specific innovations, hypotheses, and measures at baseline. Fam Med. 2011;43(7):464-471.

- Carney PA, Eiff MP, Waller E, Jones SM, Green LA. Redesigning residency training: summary findings from the preparing the personal physician for practice (p4) project. Fam Med. 2018;50(7):503-517. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2018.829131

- Miller WL, Dostal J. Transforming primary care: leadership in education, access and quality. Unpublished manuscript. Lehigh Valley Health Network Department of Family Medicine, Allentown, PA. April 2007.

- Rodríguez C, López-Roig S, Pawlikowska T, et al. The influence of academic discourses on medical students’ identification with the discipline of family medicine. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):660-670. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000572

- Foster K, Roberts C. The Heroic and the Villainous: a qualitative study characterising the role models that shaped senior doctors’ professional identity. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):206. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0731-0

- Miller WL. The clinical hand: a curricular map for relationship-centered care. Fam Med. 2004;36(5):330-335.

There are no comments for this article.