Faculty development (FD) is required for medical student and resident faculty.1,2 While the design and evaluation of FD programs has progressed,3-5 significant design and outcome gaps remain. Steinert, et al, argue that qualitative, mixed-method and control group designs would help understand program impact (eg, career impacts, building community).4,6 Therefore, we compared career development as perceived by graduates of our established, longitudinal FD program with matched nonenrolled controls.

BRIEF REPORTS

Evaluating the Career Impact of Faculty Development Using Matched Controls

Jeffrey Morzinski, PhD, MSW | Deborah Simposon, PhD | Karen Marcdante, MD | Linda A. Meurer, MD, MPH | Mary Ann Gilligan, MD, MPH | Tess Chandler

Fam Med. 2019;51(10):841-844.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2019.195240

Background and Objectives: Faculty development (FD) is required for medical educators, yet few studies address its long-term career impact on graduates. This project presents the impact of FD on career development, as perceived by physician faculty graduates of a longitudinal primary care FD educator program, compared to nonenrollees.

Methods: Between 2011 and 2016, 33 physician faculty from three departments participated in monthly half-day in-class FD for 20 months, emphasizing educator skills and career development. After physician-graduates were stratified by year, 10 were randomly selected and matched with 10 nonparticipants (controls) by specialty, gender, academic rank, and time in academic medicine. Narrative responses from semistructured interviews were recorded in a common template. Qualitative analysis methods identified themes, with agreement obtained by researchers.

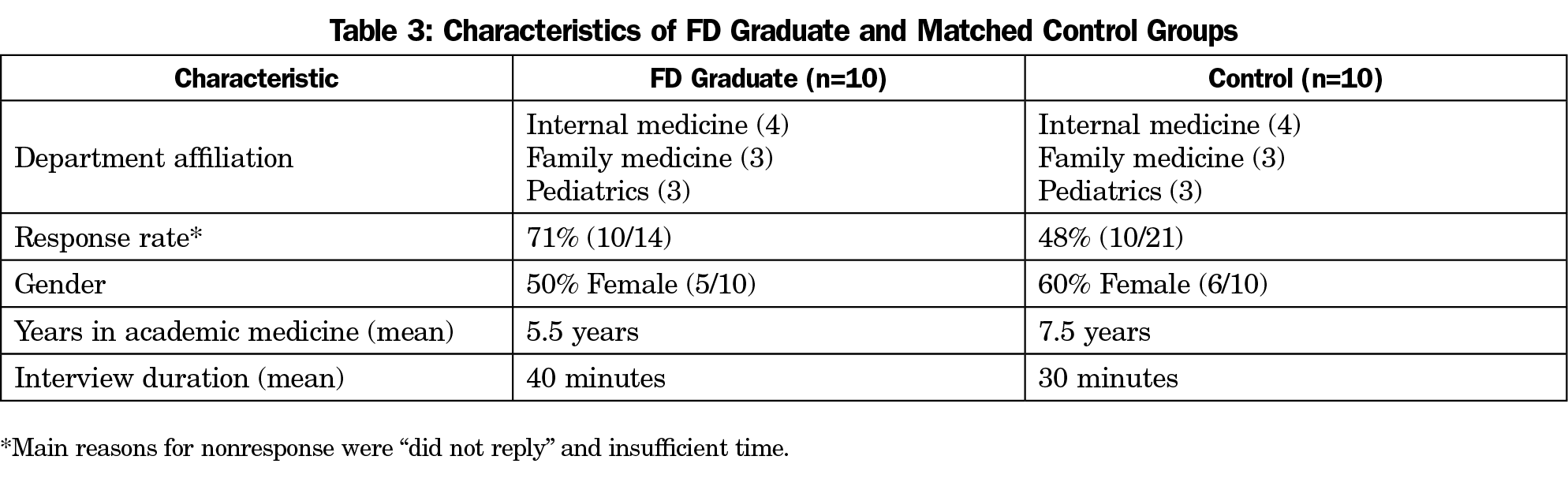

Results: Median time in academic medicine for FD graduates (50% male) was 5.5 years; controls 7.5 years (40% male). Common themes across all respondents included that they: value their roles as clinical teachers; define success as training high-quality, competent physicians; align their professional aims with organizational priorities; manage commitments; develop and sustain colleague networks; and seek continued growth. Within themes, FD graduates differed from controls, detailing greater perceived success and growth as educators, placing higher value on scholarly products and academic promotion, and having more expansive local and national colleague networks.

Conclusions: FD graduates, compared to matched controls, report expanded clinician-educator scope and roles, and a greater value on scholarly activity. This evaluation provides the groundwork for further investigations.

Faculty Development Program Description

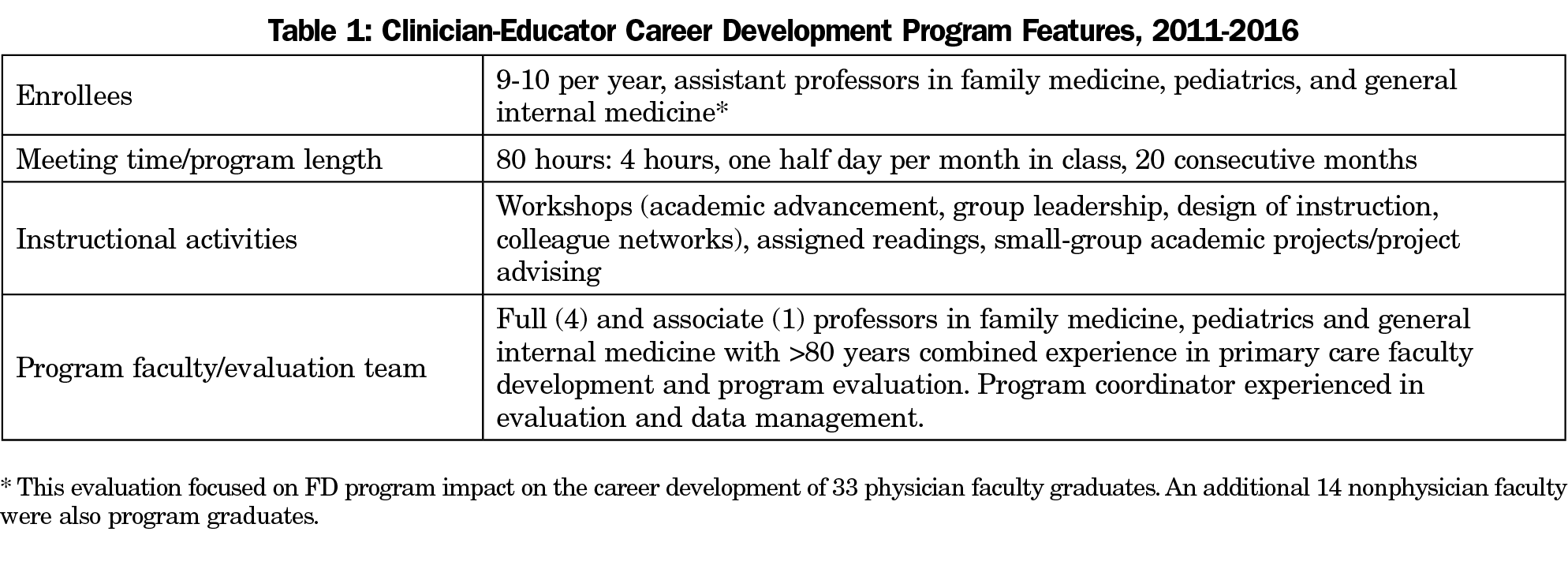

Building on a 20-year history of primary care FD at the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW),7-9 we sharpened our focus on clinician-educator career development with 80 hours per year of interactive classroom sessions between 2011 and 2016. Active participation and academic project completion were graduation criteria (Table 1).

Evaluation Approach, Participants, and Team

Seeking comparison group evaluation design, a matched control approach was selected10,11 using structured interviews consistent with constructivist, grounded theory.12 The MCW’s Institutional Review Board reviewed the study protocol and found it to be exempt.

During 2011-2016, 33 physician faculty graduated from the FD program. Graduates were stratified by year (early=2011-2013; late=2014-2016) and specialty (family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics). Ten graduates were randomly selected from these strata and matched to physician faculty controls according to gender, specialty, and years in academics. As the pool of non-FD participants was limited, we used three strategies to identify controls: (1) FD graduates’ referrals; (2) FD coleaders’ suggestions; and (3) departmental leadership recommendations.

Our evaluation team consisted of our five FD program faculty and a coordinator. All were experienced in FD evaluation using both qualitative and quantitative methods (Table 1).

Instrument and Pilot Test

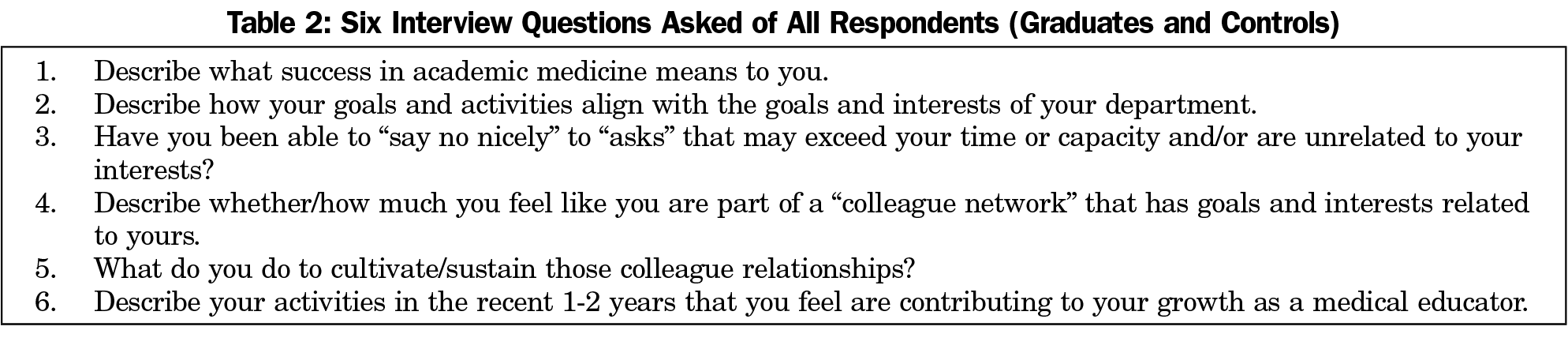

Six interview questions were based on a clinician educator career development model13 that framed key elements associated with success: alignment of interests with workplace needs, acceptance of responsibility for career growth, and participation in academic communities. The interview protocol was piloted with five experienced nonstudy eligible medical educators, informing minor protocol revisions and interview length (Table 2).

Interview Administration

After informed consent, the 10 FD graduates and controls were randomly assigned to an evaluation team member for a scheduled 30-minute telephone or in-person interview. Matched controls received up to two email invitations, with nonrespondents (more than 10 days) replaced according to the strategies above.

Interviews began with a short script reiterating the evaluation’s purpose and processes (eg, data deidentification, freedom to ignore a question), followed by the interview protocol questions (Table 2). Based on study team preferences and to limit recording/transcription costs that exceeded team resources, interviewers transcribed subject responses into a form that paralleled the protocol questions. The study coordinator labeled completed forms with unique identifiers and assured all responses were deidentified.

Narrative Analysis

The interviewer, along with a randomly assigned second team member, independently analyzed each completed response form to identify passages associated with key career development elements.13 These study member pairs then met to resolve any disagreements.12,14 The full evaluation team then discussed and agreed on overarching macro themes and associated micro subthemes, identifying representative narrative passages.

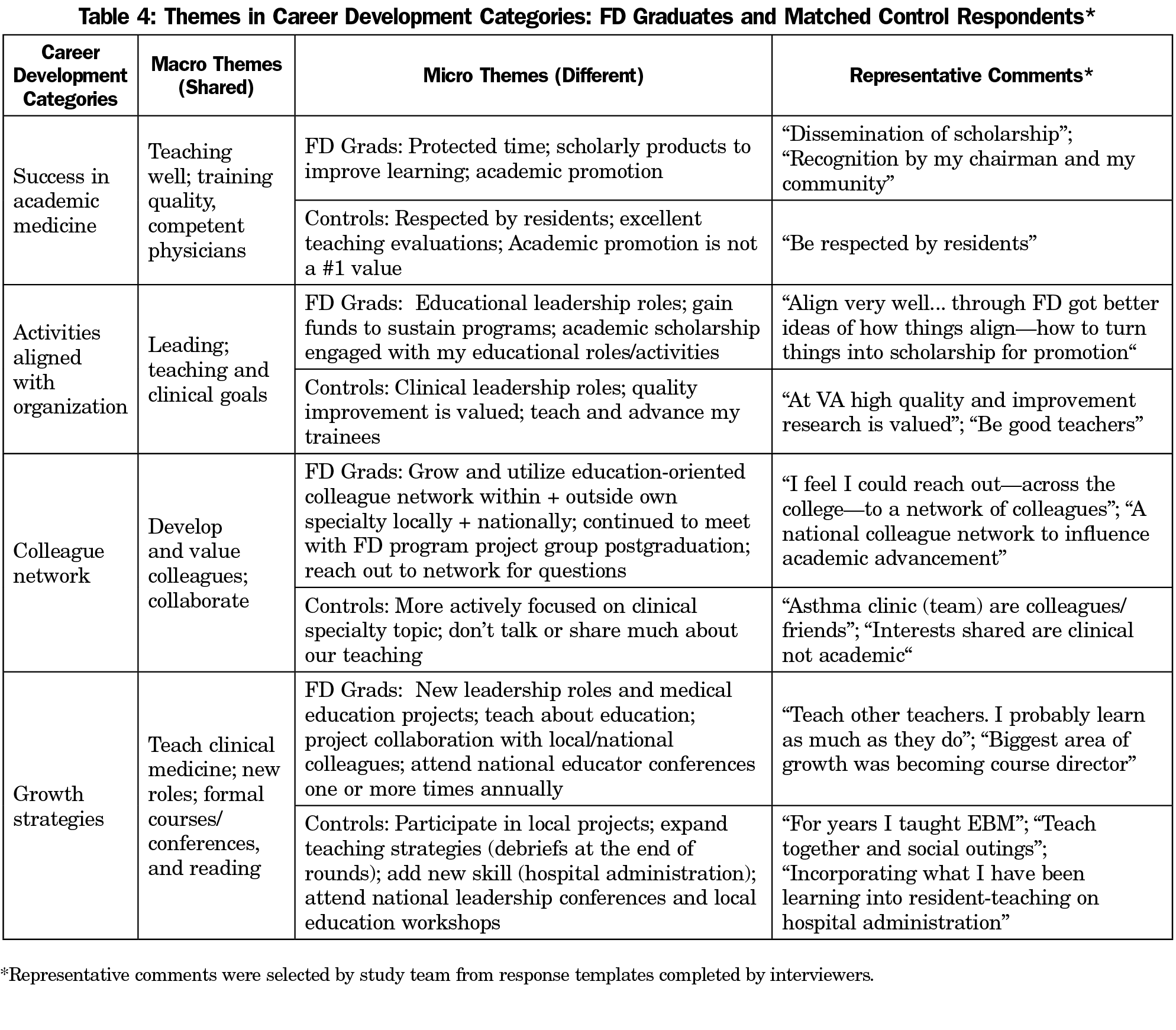

FD graduate and matched control characteristics were similar (Table 3). Consistent with the career-development model-guided interview questions,13 four career development macro themes were common across groups, with notable differences between graduates and controls identified as micro themes (Table 4).

What Success Means in Academic Medicine

On the macro level, all defined success as training high-quality, competent physicians. At the micro level, indicators of academic success differed, with graduates’ responses emphasizing scholarship and academic advancement. Controls noted disinterest in scholarship and promotion, focusing on success as teachers.

Goals and Activities Aligned With Department

At a macro level, all respondents noted shared departmental and personal interests in improving teaching and clinical goals. At the micro level, graduates reported greater alignment between personal and department goals related to medical education compared to controls.

Colleague Networks—Cultivating Colleague Relationships

All reported cultivating relationships and forming networks. However, at the micro level, graduates cultivated and sustained clinical and education colleagues through professional societies and academic projects, whereas controls’ colleagues grew mainly from “the bedrock (of) patient care.”

Growth as a Medical Educator

At the macro level, all respondents had growth strategies for teaching and leadership. They started or joined resident teaching initiatives, (rounds debrief, improving community preceptor retention) or through workshops. Both groups stressed the importance of politely saying no. “Learning my limits” improved after 2 years of faculty appointment. On the micro level, graduates aligned their education-oriented learning, conferences, and colleague networks with leadership roles.

Graduates and controls valued their clinical teaching roles with agreement across the career development macro themes. However, narratives differed at the micro level, with controls noting career paths aligned with clinical and/or important clinical teacher roles and achievements. Graduates reported greater success and growth as medical educators, placing high value on scholarly products, academic promotion through medical education, and enhanced academic colleague networks. These findings extend prior FD evaluation findings,6-9,15 and support recently articulated views that FD, scholarship, and communities of learners have advanced the evolution of clinician-educator careers.3,4,16

This study has several methodological limits. Graduates’ FD enrollment demonstrates interest in medical education, indicating possible selection bias. However, many controls reported participation in FD, typically external to our institution and of brief duration. Although the 10 graduates were randomly selected, our institution’s long-standing Primary Care FD program limited our precision in matching, due to the number of available faculty controls. Finally, while we were confident that interviewer scribing within a response template was accurate and thorough, this choice may have resulted in omissions and/or inaccuracies.

This is the first published study using matched controls to evaluate the influence of longitudinal, clinician-educator faculty development on graduates’ careers. While FD graduates and controls had some similar findings, key differences highlight FD graduates’ expanded scope and careers as clinician-educators. These evaluation results support continuing career development programming and investigation.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This project was supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant #2D55HP00093, Faculty Development in Primary Care. The study information and content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS, or the US Government.

Presentations: This project and/or its partial/preliminary findings were presented at the following meetings:

Morzinski J, Simpson D, Marcdante K, Meurer L, Gilligan MA, Chandler T. Evaluating faculty development: lessons from a matched-control, qualitative study. AAMC-Central Group on Educational Affairs. Chicago, IL. March 29-31, 2017.

Gilligan MA, Meurer L, Marcdante K, Simpson D, Morzinski J. Evaluation of a longitudinal faculty development program using a qualitative design with matched-controls. 2017. Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting. Washington, DC. April 19-22, 2017.

Morzinski J, Meurer L, Simpson D, Gilligan M, Marcdante K, Chandler T. Faculty development study to examine the early career success of primary care clinician-educators. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Meeting. San Diego, CA. May 5-9, 2017.

Morzinski JA, Marcdante K, Simpson D, Meurer LN, Gilligan M. Chandler T. Outcomes from a qualitative matched case-control study of faculty development. Research Highlights in Medical Education. AAMC Learn, Serve, Lead Annual Meeting. November 2-6, 2018. Austin, TX.

References

- Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and Structure of a Medical School. Standard 4.5 Faculty Professional Development. March 2019. http://lcme.org/publications/. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements. Revised June 10, 2018. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2019.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- Irby DM, O’Sullivan PS. Developing and rewarding teachers as educators and scholars: remarkable progress and daunting challenges. Med Educ. 2018;52(1):58-67. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13379

- Steinert Y. Faculty development: from program design and implementation to scholarship. GMS J Med Educ. 2017;34(4):Doc49.

- ASPIRE. ASPIRE to Excellence in Faculty Development. Dundee, UK: Association for Medical Education in Europe; 2016. http://aspire-to-excellence.org/. Accessed November 11, 2018.

- Steinert Y, Mann K, Anderson B, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to enhance teaching effectiveness: A 10-year update: BEME Guide No. 40. Med Teach. 2016;38(8):769-786. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2016.1181851

- Simpson D, Marcdante K, Morzinski J, et al. Fifteen years of aligning faculty development with primary care clinician-educator roles and academic advancement at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):945-953. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ACM.0000242585.59705.da

- Morzinski JA, Simpson DE. Outcomes of a comprehensive faculty development program for local, full-time faculty. Fam Med. 2003;35(6):434-439.

- Morzinski JA, Diehr S, Bower DJ, Simpson DE. A descriptive, cross-sectional study of formal mentoring for faculty. Fam Med. 1996;28(6):434-438.

- Kirkpatrick JD, Kirkpatrick WK. Kirkpatrick’s four levels of training evaluation. Alexandria, VA: Association for Talent Development Press; 2016.

- Mann CJ. Observational research methods. Research design II: cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies. Emerg Med J. 2003;20(1):54-60. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.20.1.54

- Varpio L, Martimianakis M, Mylopoulos M. Qualitative research methodologies: embracing methodological borrowing, shifting and importing. In: Cleland J, Durning SJ, eds. Researching Medical Education. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2015:245-256. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118838983.ch21

- Simpson D, Marcdante K. Crowdsourcing the Keys to Academic Career Success for Clinician Educator FD Program Graduates. Presentation at the Central Group on Educational Affairs Annual Meeting, Ypsilanti, MI, April 2016.

- Miles H. Saldana. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014.

- Morzinski JA. The influence of academic projects on the professional socialization of family medicine faculty. Fam Med. 2005;37(5):348-353.

- Greenberg L. The Evolution of the clinician–educator in the United States and Canada: personal reflections over the last 45 years. Acad Med. 2018;93(12):1764-1766. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002363

Lead Author

Jeffrey Morzinski, PhD, MSW

Affiliations: Medical College of Wisconsin, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Milwaukee, WI.

Co-Authors

Deborah Simposon, PhD - Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI

Karen Marcdante, MD - Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI

Linda A. Meurer, MD, MPH - Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI

Mary Ann Gilligan, MD, MPH - Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI

Tess Chandler - Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI

Corresponding Author

Jeffrey Morzinski, PhD, MSW

Correspondence: 8701 Watertown Plank Rd, Milwaukee, WI 53226. 414-955-4985.

Email: jmorzins@mcw.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.